Zinc Gluconate: Dive into a Vital Nutrient Compound

Tracing the Journey: Zinc Gluconate's Story

Zinc gluconate didn’t always show up in medicine cabinets and food supplements. Its roots slip back to early explorations of zinc’s role in health, when scientists saw that mineral deficiencies caused real problems for people. In the 1930s, researchers probed minerals as tools against nutritional deficits, especially with industrialization changing diets. Eventually, they figured out that attaching zinc to gluconic acid made zinc easier for the body to absorb. Pharmaceutical firms began mass producing zinc gluconate in the 1970s, after seeing that the compound helped the immune system and supported recovery from colds.

Product at a Glance: What Is Zinc Gluconate?

Zinc gluconate combines the mineral zinc with gluconic acid, forming a salt that dissolves in water. It lands among the preferred forms for supplementation, both because people’s bodies can use it efficiently and because it’s generally gentle on stomachs. Tablets, lozenges, syrups, and powders often draw from it. The compound flows through pharmacies, dietary supplements, animal feeds, over-the-counter cold remedies, and fortified foods. Since zinc’s vital for enzymes, DNA production, cell division, and immune responses, people reach for zinc gluconate not just to top up nutrition but also to target specific health benefits.

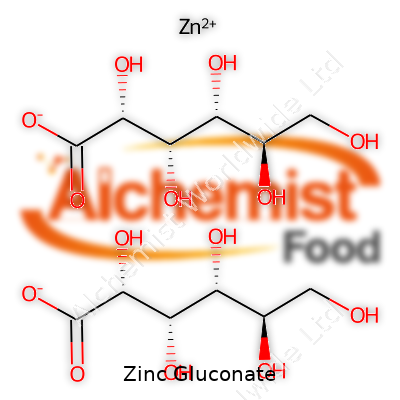

Getting to Know the Details: Physical & Chemical Properties

Zinc gluconate comes as a white to off-white powder or granule with virtually no odor. It’s got a mild, slightly bitter taste—one reason why lozenge makers often mask it with sweeteners or flavors. Chemically, its formula is C12H22O14Zn, with a molar mass of roughly 455.7 g/mol. It melts at about 172°C and dissolves easily in water, but not in most organic solvents. This water solubility matters: it lets manufacturers deliver reliable doses whether they’re mixing up a tablet, a drink mix, or an oral suspension.

The Technical Side: Specifications & Labeling Standards

Pharmacopeias like USP and EP list strict specifications for zinc gluconate. Purity sits above 97%, with heavy metal contamination and residual solvents well below dangerous levels. Authorized products state total zinc content per dose, batch numbers, expiration dates, and directions for safe use on their labels. Manufacturers run multiple tests for identity, heavy metals, arsenic, and microbial counts. Regulations keep changing as researchers learn more about trace contamination and bioavailability in finished forms, especially as supplements reach younger populations.

How It’s Made: Preparation Methods

Most zinc gluconate starts with zinc oxide or zinc carbonate. These zinc sources undergo reaction with gluconic acid, heated and stirred to create the salt. Once the solution reaches the right conditions, the compound crystallizes out. Factories filter, wash, and dry the crystals. The whole process must avoid contamination since the end product often heads into foods and medicines. Consistent particle size and low water content help in tableting and ensure each dose works as expected.

Chasing Reactions: Chemical Modifications & Developments

Chemists play around with zinc gluconate to see if they can boost stability, absorption, or taste. Modifications might revolve around making it less bitter for chewables or faster-dissolving for rapid delivery. Sometimes, researchers adjust reaction pH or purification steps to limit by-products. Few chemical reactions beat the parent zinc gluconate for safety and effectiveness, so most tweaks aim more at convenience or taste, not changing the core structure.

What’s in a Name? Synonyms & Trade Products

Zinc gluconate pops up in ingredient decks with alternative names: Gluconic acid, zinc salt; Zinc(II) gluconate; and just plain “zinc salt of gluconic acid.” Some supplement firms brand it with catchy health-centric names. Drug and nutraceutical directories list hundreds of brands using zinc gluconate, opted for cold lozenges, multivitamin capsules, or infant formulas. Shoppers need to check labels, since “zinc supplement” sometimes means zinc gluconate and sometimes points to other forms.

Keeping People Safe: Handling & Regulation Standards

Production lines for zinc gluconate don’t cut corners on safety. FDA, EFSA, and other regulatory groups set strict limits—a daily adult dose typically maxes at 50mg of elemental zinc, above which toxicity can creep in. Factories demand personal protective equipment, dust control, and ventilation. Storage happens in cool, dry, dark places, away from chemicals that could spoil the zinc. Finished product moves with traceable records from plant to pharmacy. Random lot testing and consumer hotline numbers help recall batches that slip past initial screens. People who handle or take the compound need education about dosing since taking too much for too long knocks down copper absorption and causes nausea.

Wide-Ranging Roles: Where Zinc Gluconate Finds Use

Doctors turn to zinc gluconate for patients with diagnosed deficiencies, from chronic illnesses to pregnancy. Cold lozenges with zinc gluconate get used to shorten colds, though studies debate just how much they help. Veterinarians add it to pet food and farm animal feed for healthy growth. Food technologists use it to fortify cereals, juices, infant formulas, and nutrition bars. Cosmetic chemists experiment with it in acne creams. While most people get enough zinc from food, some groups—kids, pregnant women, vegetarians, and older adults—lean on supplements, so zinc gluconate remains a centerpiece in their routines.

Pushing Boundaries: Research & Development Trends

Academic labs and supplement companies chase new ways for zinc gluconate to boost health. Some studies link it to improved wound healing or less severe respiratory infections, but more large long-term trials are needed to lock down benefits. Scientists try pairing it with vitamin C or elderberry in combination products, hoping for a one-two punch against illnesses. Delivery systems like nano-particles and slow-release coatings get explored for longer-lasting blood levels. Emerging research presses into treating severe diarrhea in low-income countries, highlighting zinc gluconate’s role in global health.

Toxicity: Hard Lines & Safety Gaps

Despite its essential role, zinc gluconate walks a tightrope. Short-term, high-dose use can irritate mouths and leave a metallic aftertaste. Over months, too much can hammer the immune system, lower “good” cholesterol, and block copper. Poison control centers receive calls from accidental child overdoses, so packaging design and awareness campaigns keep getting overhauled. Some animal studies explore chronic exposure, focusing on kidney and nerve health. Most national nutrition boards keep maximum safe zinc intake at or below 40mg per day for adults. Real-world cases of toxicity pop up mainly with “mega-dose” trends or mislabeled products, underscoring the need for clear dosing, honest labeling, and public education.

Looking Down the Road: Future Prospects of Zinc Gluconate

People aren’t done with zinc gluconate—far from it. With a growing focus on immune health since the pandemic, more products tout its inclusion. Product development leans into forms kids enjoy, supplements easier for seniors to swallow, and formulations targeting sports recovery. Export markets in low- and middle-income countries tick up as supplement programs expand. Researchers look at new health claims, such as support for mental focus or sports injuries, collecting stronger evidence as they go. Ongoing advances in quality control, purity, and delivery methods promise an even safer, more effective future for this time-tested supplement.

What is zinc gluconate used for?

Everyday Uses Backed by Science

Zinc gluconate comes up a lot, especially during cold and flu season. I remember that sudden urge to reach for lozenges the moment my throat tickles, hoping for a shortcut through the misery. It turns out, zinc gluconate isn’t just another supplement you grab from the shelf. Researchers have shown it can actually help shorten the length of the common cold. Not every "remedy" stacks up under a microscope, but a meta-analysis in The Cochrane Library reported a significant reduction in cold duration for people who began zinc lozenges within twenty-four hours of symptoms. Those wanting to get back on their feet can find some comfort in that kind of data.

Immunity Needs More Than a Quick Fix

People talk about immunity like it’s a simple switch. Real immunity takes more than one pill, but zinc gluconate forms an important piece of the puzzle. In practice, I’ve seen friends get run down by stress, lack of sleep, or rough weather. Getting enough zinc from diet alone isn’t a given. Beans, whole grains, and even nuts contain phytates, which make it tougher to pull the mineral out of your meal. Supplementing with zinc gluconate can help balance out these shortfalls. It’s not just about fighting off a cold but making sure the immune system has the resources it needs to work properly.

More Than Just Cold Relief

Zinc’s role in the body reaches far beyond sniffles. It helps wounds heal, keeps the sense of taste sharp, and supports vision. Zinc gluconate, because of its good solubility in water and moderate absorption in the gut, is often the form found in supplements. Some evidence from clinical nutrition journals suggests zinc supplementation may help those with chronic wounds or skin disorders such as acne. It’s not a miracle cure, but steady support for body systems that most of us take for granted until something goes wrong.

Safety and Smart Use

No supplement comes risk-free. While zinc is critical in many body processes, more doesn’t always mean better. People who load up on zinc gluconate without giving their copper intake a thought can unintentionally bring on a new problem—copper deficiency. That leads to its own set of troubles, like anemia or nerve issues. The National Institutes of Health recommend a daily upper limit of forty milligrams for adults to avoid these problems.

Solutions That Respect Real Life

Making health choices often gets complicated by marketing buzz and rumors. Experience and research both point to a simple fact: zinc gluconate can be useful, but works best as part of a bigger picture. Folks interested in starting a supplement ought to talk with a registered dietitian or a physician to sort out what’s genuinely useful and what’s just the latest trend. Sometimes, a blood test or diet review will reveal whether there’s a need for more zinc at all.

Keeping Wellness in Context

When considering zinc gluconate, think about eating habits, overall health, and the advice of professionals. No supplement stands in for real food, plenty of water, and enough rest. Those seeking fewer sick days or better recovery from minor wounds can benefit, as long as they make zinc gluconate part of a bigger wellness plan, not the whole story.

What is the recommended dosage of zinc gluconate?

Why Zinc Even Matters for Health

Every cell in the body needs zinc. This mineral keeps your immune system sharp and helps wounds heal faster. Many turn to zinc supplements, especially during cold season, hoping for fewer sick days. One of the most popular forms out there? Zinc gluconate, because it’s easy on the stomach and easy to find.

How Much Zinc Gluconate Makes Sense?

Zinc is measured in milligrams, but there’s a twist. A 50 mg zinc gluconate tablet doesn’t give you 50 mg of elemental zinc. Only about 7 mg in that tablet comes as actual zinc. The rest is the gluconate part. The recommended daily allowance (RDA) for adults lands at 8 mg for women, 11 mg for men. That’s total zinc for the whole day, not just supplements. If you eat meat, dairy, nuts, or beans, you're already getting some zinc through regular meals.

What Doctors Actually Recommend

Most over-the-counter zinc gluconate products come in 50 mg tablets. Taking one of these each day often tips you far over the RDA. For short-term use, like fighting a cold, some doctors suggest 15–25 mg elemental zinc each day, but not longer than a week or two. Taking more for long stretches starts causing problems: copper deficiency, stomach upset, even lower immunity. It's easy to think more zinc means more benefits, but the science doesn’t back that up.

Why More Isn't Better

Overshooting your zinc needs can stack up side effects. I’ve seen people develop serious stomach pains and odd changes in taste. Too much zinc can actually block the body’s use of other minerals, especially copper. This is a lesson I picked up after a family member kept popping zinc lozenges every few hours, convinced they were an immune booster. They ended up with nasty stomach issues instead. High doses can also throw off cholesterol levels and damage nerve function over time.

What Science Really Says

Plenty of research looked into zinc and catching colds. Most studies used lozenges delivering around 9–24 mg elemental zinc every 2–3 hours during the day, for a few days at a time. No solid evidence supports long-term daily use in healthy people. The National Institutes of Health points out that staying near the RDA offers safety and effectiveness for most.

The Smarter Way to Use Zinc Supplements

Reading bottles in the supplement aisle, I see numbers all over the place. Don’t guess—check the label for how much elemental zinc you’re getting. If you’re considering taking more than what food gives, talk with a doctor or dietitian. Balancing your minerals is more important than chasing megadoses. If you already eat meats, nuts, or whole grains, you might not even need a pill. If a blood test confirms you’re low, then supplementing can help—just in the right dose.

Practical Advice for Everyday Use

Sticking close to 8–11 mg elemental zinc per day keeps you in the clear for most healthy adults. For supplements, figure out the actual elemental zinc, since not all types are the same. Short-term use for sniffles? Use as directed and stop after a week or two. Let your healthcare provider know about any supplement plans, especially if you take daily medications or have health problems like kidney issues.

Zinc works best as part of a bigger health picture: decent meals, enough sleep, and regular movement.

Are there any side effects of taking zinc gluconate?

Looking Past the Hype

Plenty of people grab a bottle of zinc gluconate when cold and flu season ramps up. Supermarket shelves are lined with lozenges, pills, and sprays, all promising an immune boost. But behind the marketing, people often forget about the basics—anything swallowed in pill form can have a downside, even something as simple as a mineral. Drawing from experience as well as trusted science, let’s talk about what really happens when you load up on zinc gluconate, and why it matters to take dosage and your own needs seriously.

Common Side Effects You Might Notice

Nobody likes stomach aches or feeling queasy, especially right after trying to do something healthy. Zinc, in the form of gluconate, can stir up your gut pretty fast. Nausea, indigestion, and stomach cramps show up time and again in people who take too much, particularly on an empty stomach. Research from sources like the Mayo Clinic notes that doses above 40 milligrams per day increase this risk.

On a few busy mornings, I’ve popped a zinc lozenge before breakfast and regretted it the whole drive to work. That queasy, metallic taste doesn’t go unnoticed. Friends and patients I’ve talked with mention the same thing: zinc is far from gentle if you’re prone to sensitive digestion. If you’re already dealing with gastrointestinal problems like ulcers or IBS, even the mildest symptoms can get worse fast.

Long-Term Risks Aren’t Always Obvious

Imagine refilling that supplement bottle every month. Over time, zinc starts to interfere with copper absorption in your gut. Too much zinc can actually set off a copper deficiency. That matters for your nerves, your blood, and your immune system far more than skipping a supplement ever could. Data from Harvard Health points out that copper deficiency can bring on numbness, anemia, and trouble fighting infection.

Your sense of taste and smell also rely on balanced minerals. Oddly enough, excess zinc may blunt taste and olfactory nerves, the very senses some supplements promise to help. Many people have reported losing their sense of smell after using nasal sprays with zinc gluconate. The FDA even warned against these products after reports of permanent loss of smell. Swallowing the mineral in pill or lozenge form won’t usually cause this, but it shows how even trace minerals can have big effects.

Interactions With Other Nutrients and Medicines

Zinc doesn’t work in isolation. Take it with certain medications—antibiotics like tetracycline or supplements with iron or calcium—and the absorption of both zinc and the medicine can drop. So if you’re treating an infection or managing another deficiency, piling on zinc might slow your recovery down. Health authorities like the National Institutes of Health recommend separating zinc and iron or calcium supplements by at least a few hours to play it safe.

Where Science Points for Smarter Use

Doctors and nutritionists agree that most healthy adults don’t need more than 11 milligrams of zinc per day, which you can get from a couple of ounces of beef, chickpeas, or pumpkin seeds. If you think you need more, it makes the most sense to talk to a healthcare professional who knows your background and actual needs. Simple bloodwork can spot any real deficiency before adding extra pills to your bathroom shelf.

Supplements exist to fill gaps, not to replace whole foods or become a daily crutch. With real risks in mind, anyone considering zinc gluconate should treat it like any other tool—helpful, but only if it doesn’t cause more harm than good.

Can I take zinc gluconate daily?

Zinc’s Spot in Everyday Health

Zinc finds its way into plenty of conversations whenever a friend catches a cold or someone wants to feel a bit more energetic. Many swear by zinc lozenges, especially in winter. Zinc gluconate, with its manageable taste and price tag, often ends up as the go-to supplement on those pharmacy shelves. It’s hard to ignore claims about zinc and immunity, but the real decision isn’t as simple as “pop one daily and you’ll feel invincible.”

What Zinc Actually Does

Zinc supports immune cells, helps heal wounds, and assists your body in using carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. Not only does zinc play a role in growth and DNA building, it’s also involved in over 300 enzymes. If you don’t get enough, your appetite drops, wounds drag out, your taste dulls, and you might find yourself getting sick more often.

Meeting your body’s zinc requirement from food should be possible. Meat, shellfish, nuts, dairy, and beans all pitch in, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Beef, crab, and chickpeas stand out for their zinc content. Many cereals and snack bars also contain added zinc. Most adults require about 8-11 mg daily, which isn’t too hard if you rotate healthy staples in your meals.

How Much Is Too Much?

The easy access to zinc supplements can make daily use tempting. I’ve talked to people convinced that a little extra “insurance” will fend off every cold. But regularly topping up with high doses through zinc gluconate supplements pushes you above recommended intake levels. The NIH sets a tolerable upper limit for adults at 40 mg each day. Consistently overshooting that can mess with your copper absorption, bring on nausea, lower your immunity, and even affect cholesterol levels.

Some folks, such as vegetarians or pregnant and breastfeeding women, need a bit more zinc or absorb it less efficiently. Health professionals might recommend supplements for them. But taking zinc “just because” isn’t usually needed if you’re eating well.

The Downside of Daily Pills

A handful of people reach for zinc every morning in hopes that it keeps every sniffle at bay. Daily use without a clear medical reason or lab evidence of deficiency doesn’t just waste money, it sometimes delays real answers when people keep feeling tired or unwell. Side effects like a funny taste, upset stomach, or headaches often come up in these groups. There’s also risk in “stacking” zinc from multivitamins, cold lozenges, and fortified foods without realizing it.

There’s little benefit in “supercharging” your body if you already get what you need through your meals. Unexplained low energy, catching every bug that comes around, or delayed healing call for real conversations with your doctor and possibly a blood test—not just self-dosing with zinc gluconate.

Smarter Steps Moving Forward

Turning to supplement bottles should not replace real food, balanced meals, or medical guidance. A registered dietitian, doctor, or pharmacist can weigh in if you wonder about zinc or any other supplement. Paying attention to what your body tells you does much more than any trend-driven pill. For most healthy adults, meeting nutrition targets doesn’t require putting zinc gluconate on the daily checklist.

If you’re concerned about your zinc intake or curious about whether your multivitamin already covers it, go over the labels and talk to a trusted professional. Building true health takes more than riding the latest supplement trend.

Is zinc gluconate safe during pregnancy?

Digging Into Zinc and Its Role During Pregnancy

Zinc plays a key part in supporting a healthy pregnancy. This trace mineral helps enzymes do their jobs, supports immune function, and promotes healthy DNA. For anyone who’s ever experienced odd cravings or sudden fatigue during pregnancy, nutrient balance could play a part. Low zinc can show up as lingering colds, poor wound healing, and even slower growth in children.

The American Pregnancy Association says pregnant people need about 11 mg of zinc every day. That means a bit more than most adults. Some get there through red meat, beans, nuts, whole grains, and dairy, but not everyone eats all those foods. Vegetarian diets or stomach issues like morning sickness can make it harder to get enough zinc from food alone.

Supplements Step In: The Role of Zinc Gluconate

Zinc gluconate often finds its way into prenatal vitamins or appears as a stand-alone supplement at the drugstore. It’s considered a form of zinc that the body can absorb fairly well. If you ever scanned the back of a prenatal bottle at the grocery store, you’ve probably seen zinc gluconate listed. Doctors sometimes recommend it for folks whose bloodwork shows they’re not getting enough zinc naturally.

Using supplements isn’t the same thing as snacking on pumpkin seeds or a beef taco. Taking too much zinc can backfire. High levels can block copper absorption, mess with iron status, or cause issues like nausea and stomach pain. According to the National Institutes of Health, 40 mg per day is considered the upper safety limit for adults—including pregnant women.

Safety: What’s Proven and What Isn’t

Zinc supplements like zinc gluconate have been around for years, and no strong evidence links them to birth defects or big complications when taken at reasonable doses during pregnancy. Multiple studies suggest that taking appropriate levels helps lower the risk of small birth weight and preterm birth, especially in places where regular zinc intake is low. Still, taking big doses for long stretches doesn't bring extra benefits and can sometimes cause trouble.

Nutrition guidelines from the CDC and ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) encourage pregnant people to get nutrients from food, using supplements to fill gaps rather than as the main source. Zinc gluconate seems safe at recommended amounts, but loading up "just in case" delivers no perk and potential risk.

Knowing What’s Right for Your Body

If you’re expecting and thinking about zinc gluconate, the best step is checking in with your doctor or midwife. Simple blood work can point out true deficiencies, and a prenatal vitamin with a moderate dose usually covers what you need. If you’re already getting a healthy variety of foods, an added supplement may not do much. On the flip side, diets low in red meat, eggs, or fortified breakfast cereals—common during pregnancy from aversions or food restrictions—may call for a careful boost.

Focusing on Balance and Real Needs

Diving into supplements without a reason isn’t magic. Real stories from parents show that trusting your team and talking openly about eatings habits works better than guessing. One friend of mine spent her first trimester eating little more than bread and cheese—her doctor flagged low zinc and helped find a simple fix. No scare stories, just an evidence-based adjustment tailored for her. For others, no supplement was needed at all. Everyone’s body and story is different.

Zinc gluconate can safely support a healthy pregnancy for people with true dietary gaps or medical needs, as long as it’s used thoughtfully and within recommended limits. The most helpful approach involves working closely with a healthcare provider and respecting that no pill beats a varied, nourishing diet.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | zinc bis[(2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate] |

| Other names |

Zincum gluconicum Gluconic acid zinc salt Gluconate de zinc Zinc(II) gluconate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈzɪŋk ˈɡluː.kə.neɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | zinc;2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate |

| Other names |

Zincum Gluconicum Gluconic acid zinc salt Gluconate de zinc Zinc(II) gluconate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈzɪŋk ˈɡluːkəˌneɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 4468-02-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1723995 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9574 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201560 |

| ChemSpider | 54618 |

| DrugBank | DB01378 |

| ECHA InfoCard | DTXSID20873952 |

| EC Number | 231-072-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 87838 |

| KEGG | C15616 |

| MeSH | D015599 |

| PubChem CID | 24851632 |

| RTECS number | ZWU135700 |

| UNII | JTG9297Q2B |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | FJT0W2B08P |

| CAS Number | 4468-02-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1105051 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:132948 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201534 |

| ChemSpider | 16136 |

| DrugBank | DB00119 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b4b1f5-3a4a-4e0d-912d-c6b17101d869 |

| EC Number | 231-072-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 371786 |

| KEGG | C00292 |

| MeSH | D015399 |

| PubChem CID | 24839738 |

| RTECS number | ZH5200000 |

| UNII | J9A54X0806 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C12H22O14Zn |

| Molar mass | 455.686 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 0.75 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble in water |

| log P | -1.7 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa ≈ 3.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.8 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.56 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 1.82 D |

| Chemical formula | C12H22O14Zn |

| Molar mass | 455.686 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or almost white, crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 0.7 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble |

| log P | -3.72 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 3.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.33 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Dipole moment | 3.52 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | Visit specific chemical databases or literature sources for the standard molar entropy (S⦵298) value of Zinc Gluconate, as it is not widely tabulated. |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1564.6 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 757.49 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1564.6 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CB01 |

| ATC code | A12CB01 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. Harmful if swallowed. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315: Causes skin irritation. H319: Causes serious eye irritation. H335: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3500 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 143 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WZ3850000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg Zn |

| REL (Recommended) | 11 mg (as elemental zinc) |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 |

| Pictograms | Acute toxicity, Health hazard, Exclamation mark, Environment |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | No hazard statements. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3500 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 3500 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | RN8750000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 11 mg (elemental zinc) daily |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Gluconic acid Calcium gluconate Copper gluconate Ferrous gluconate Manganese gluconate Potassium gluconate Magnesium gluconate Sodium gluconate Zinc sulfate Zinc acetate |

| Related compounds |

Gluconic acid Calcium gluconate Potassium gluconate Magnesium gluconate Zinc sulfate Zinc acetate Zinc oxide Zinc chloride |