Xylitol: The Science, Safety, and Promise Behind a Sweet Alternative

Historical Development

Xylitol originally showed up in the early 1890s, with researchers in both Germany and France managing to isolate this sugar alcohol from sources like beech wood. Decades later, in the scarcity-driven days of World War II, Finnish scientists began looking harder at xylitol as a sugar substitute. Their findings helped lay the groundwork for modern industrial production. Once the world caught on to its potential, especially in dental care, manufacturers began extracting xylitol at scale from corn cobs and birch wood, which are both pretty abundant and renewable. Early research, paired with national needs and agricultural surplus, played a huge role in propelling xylitol’s popularity and spread.

Product Overview

Xylitol’s claim to fame comes from its sugar-like taste without the blood sugar spikes. It blends the mouthfeel and sweetness of table sugar with a significant drop in calories, about forty percent less. Grocery store shelves stack gum, mints, toothpaste, and even bakery goods containing xylitol. It often appears as white, crystalline granules, indistinguishable from sugar to the naked eye. Some products tap into its sweetness, while others focus on dental health. Its use in diabetic-friendly foods speaks to its low glycemic index, letting people with blood sugar concerns enjoy treats with much less worry.

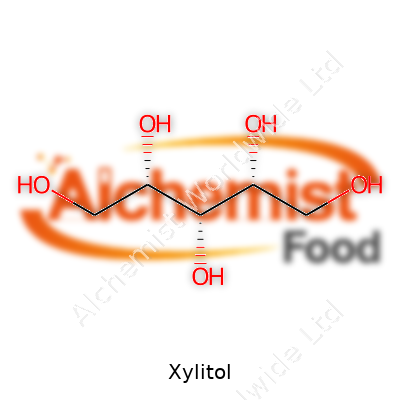

Physical & Chemical Properties

Xylitol stands out because it looks, pours, and dissolves just like granulated sugar. The crystals multipurpose well in both home kitchens and industrial recipes. With a molecular formula of C5H12O5, xylitol counts as a five-carbon sugar alcohol, which means the body metabolizes it without needing insulin. It’s heat-stable, resists browning, and handles repeated freezing and thawing without breaking down. Its solubility in water measures even higher than sucrose at room temperature, and it leaves a cooling sensation on the tongue thanks to endothermic dissolution. For shelf life, xylitol packs strong resistance to moisture gain, which keeps products drier and clump-free over time.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Food-grade xylitol usually appears as fine, crystalline powder with at least ninety-eight percent purity, often tested by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anyone who works with food or drugs sees xylitol labeled under strict codes—United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and European Pharmacopoeia (EP) both publish benchmarks. Packages must show country of origin, net weight, and batch numbers for traceability. For consumers with allergies or intolerances, xylitol’s plant origin matters, so traceability onto the raw feedstock—corn, birch, or other—often goes on labels, too. Regulatory watchdogs like the FDA and EFSA recognize xylitol as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS). For exports, compliance checks cover purity, foreign matter, heavy metals, and microbe testing, all spelled out in import documentation.

Preparation Method

The modern xylitol manufacturing process starts by extracting xylan-rich hemicellulose from plant materials, especially hardwood or agricultural waste such as corn cobs. The process continues by hydrolyzing xylan into xylose with acid or enzymes. Chemists then reduce xylose hydrogenation using sophisticated catalytic reactors, often with Raney nickel, producing xylitol directly. After that, purification steps chase out impurities and color. These include activated carbon treatment, ion exchange, crystallization, and sometimes spray drying, which delivers a finished product ready for food and pharmaceutical use. This process manages to turn agricultural byproducts, which would otherwise go to waste, into something valuable, sweet, and safe.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Xylitol keeps its structure under most standard food processing conditions. Because of its stability, chemical changes rarely happen during cooking or storage, but it can react with certain acids or oxidizers under lab conditions. Chemists have tried attaching other sugar molecules to create xylitol derivatives, which promise new medicinal or nutritional uses. Its five hydroxyl groups open up options for esterification or etherification, which has led to research in surfactants and anti-microbial agents. Microbes like Candida albicans metabolize xylitol poorly, which adds to its reputation for dental health—bacteria can’t turn it into tooth-harming acids easily, limiting plaque buildup.

Synonyms & Product Names

Xylitol goes by several names in the trade: birch sugar, wood sugar, and E967—the food additive code for labeling in Europe. Suppliers often use product names tied to the raw material, like “corn xylitol” or “birch xylitol.” In ingredient lists, both technical and simplified language appear, so shoppers see xylitol, sugar alcohols, or polyols. For people searching scientific literature, D-xylitol is a common synonym. Despite the naming variety, purity standards keep products consistent no matter their branded label or source.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety studies on xylitol stretch back decades. The FDA and EFSA back xylitol’s general safety, but industry guidelines focus on storage hygiene and food sanitation to protect quality through handling. Manufacturers control dust to keep the air safe and avoid powder explosions in busy plants. Equipment must run with stainless steel or food-safe plastics, avoiding contamination. Companies monitor temperature and humidity, as xylitol’s hygroscopic nature could lead to clumping or spoilage. Product packaging needs robust sealing, minimizing water uptake and microbial risk. Altogether, strict procedures build confidence for buyers and end-users while minimizing recalls or health scares.

Application Area

Xylitol helps reduce cavities, so the dental industry uses it in gums, pastes, and rinses. Pharmaceutical companies add it to tablets and lozenges for a sweet boost without sugar’s energy punch. Bakers and snack makers tap xylitol for cookies, cakes, protein bars, and diabetic-friendly alternatives, sometimes as the lone sweetener or mixed with others. Beverage makers catch onto xylitol as both a flavoring and mouthfeel enhancer, particularly in drinks for people watching calories or carbs. Even in pet foods, awareness grows—though, crucially, xylitol stays strictly off-limits for dogs, since it poses severe toxicity for them. Industries keep finding new uses, drawn by xylitol’s sweetness, texture, and health angle.

Research & Development

Studies continue to dig into how xylitol affects oral bacteria and whole-body metabolism. Dental trials have shown meaningful drops in Streptococcus mutans after regular use, supporting claims of cavity protection. Researchers also test how xylitol may help patients with dry mouth and ear infections. Academic labs look for greener, less energy-intensive production paths—using engineered yeasts or fungi to produce xylose more efficiently. Ongoing studies try to optimize hydrogenation catalysts and cut down processing time, upping sustainability. There’s a steady stream of medical and food tech advances, each hoping to make xylitol easier and cheaper to produce or use.

Toxicity Research

Human studies show people tolerate xylitol pretty well in moderate doses. Eating large amounts—say over fifty grams a day—can cause bloating or laxative effects, since unabsorbed polyols draw water into the gut. Standard dietary guidelines flag this with “may cause laxative effects” warnings on high-content products. Xylitol’s safety changes when dogs get involved: doses as low as seventy-five to a hundred milligrams per kilogram can trigger insulin surges, drop blood sugar dangerously, or harm the liver. Emergency vets know the signs and encourage immediate treatment, which is why all pet food and treat manufacturers steer clear of xylitol. No credible studies link xylitol with carcinogenic or genetic damage in humans, supporting its approval for daily human use.

Future Prospects

Demand for low-calorie, non-cariogenic sweets is only climbing, and xylitol stands ready for a larger share of food and dental markets. As populations grow more health-aware, food makers look for sweeteners that fit both lifestyle needs and regulatory demands. Tech improvements could open doors for even cheaper xylitol sourced from straw, bagasse, or other bio-waste, helping the environment as well as wallets. Tooth decay remains a global problem, especially where sugar consumption runs high, so low-glycemic options like xylitol could play a bigger part in public health. If new research holds, expect to see expanded use in oral care, pharmaceuticals, and possibly even animal health (with strict species limitations). As consumers look for transparent labeling, and as the world keeps focus on planetary health, xylitol’s role as a renewable, relatively safe sweetener seems set to keep growing.

What is xylitol and how is it used?

What Is Xylitol?

Xylitol isn’t a new name for folks interested in healthy options or sugar substitutes. This sweetener comes from plants—corn cobs and birch wood make up its main sources. Chemically, xylitol lands in the sugar alcohol family, but it still looks and tastes like sugar. Xylitol doesn’t spike blood sugar the way table sugar does. That simple fact already changes the story for people managing diabetes or just aiming for lower daily sugar intake.

Everyday Uses of Xylitol

One look down a candy or gum aisle and you’ll spot xylitol’s influence. Chewing gums, mints, and some toothpastes now use it because the stuff can actually block cavity-causing bacteria from clinging to teeth. From my experience as someone who checks ingredient labels, I admire that xylitol manages to keep things sweet without encouraging dental problems. Some sugar-free chocolates, protein bars, and baked goods use it as well, creating more options for those who want sweetness without sugar’s hit to the waistline or blood sugar.

Why Xylitol Matters

Many of us try to reduce sugar, but finding a good alternative isn’t simple. Sucralose and aspartame have their critics, sometimes over taste and sometimes over potential side effects. Xylitol stands out because it actually comes from natural sources and brings a mouthfeel closer to ordinary sugar. Dietitians often recommend it as a low-calorie sweetener because the body absorbs less of it, leading to smaller swings in blood sugar. That’s no small thing for people with pre-diabetes, diabetes, or even for parents trying to limit their kids’ sugar but still want birthdays to feel sweet.

Health Claims and Real Facts

Some health claims about xylitol hold up, especially the research on dental health. According to studies published by the American Dental Association, gums with xylitol lower the risk of cavities. The reason: bacteria in the mouth can’t use xylitol for energy. As a result, acid production drops, helping to protect tooth enamel.

Digestion changes though. Too much xylitol (often more than 30 grams per day) can trigger bloating, gas, or diarrhea in some folks. It’s smart to start slow and see how your gut reacts. Children and pets, dogs in particular, need extra caution. For dogs, even a small amount can cause low blood sugar and liver failure. Awareness here means keeping sugar-free gum and candies well out of paw’s reach.

Where We Can Go from Here

People will keep looking for low-calorie, real-tasting sugar alternatives, so the interest in xylitol isn’t going away. Food companies must check labels clearly—pet owners benefit most from knowing what’s hidden in their pantry. Educators and dental professionals can keep talking to families about safe ways to include xylitol in their diets. For my own kitchen, I’ve replaced some regular sugar with xylitol in recipes—oatmeal cookies, especially—and the results don’t disappoint.

Across the board, xylitol opens up opportunities. Not perfect, not magic, but a step toward better health for lots of people willing to read a label and learn what fits their needs best.

Is xylitol safe for diabetics?

What Xylitol Really Offers

Xylitol sweetens many "sugar-free" gums, candies, and some baked snacks in the store, and lots of people dealing with diabetes have asked if they can use it safely. The simple answer comes from how xylitol works in the body. It's a type of sugar alcohol, pulled from plants like birch, and it doesn’t raise blood sugar to the same degree as table sugar. This makes it sound like a free pass for those trying to keep their blood sugar in check. But, like plenty of things you find in stores, there’s more to it than a label or a quick promise.

Glycemic Impact and Real-World Effects

Xylitol’s main draw for people with diabetes comes from its low glycemic index. The value for xylitol falls at about 7, where glucose stands at 100 and table sugar hovers around 60. That difference means eating xylitol doesn’t lead to big, sudden jumps in blood sugar. That right there, for someone like me who has seen loved ones prick their fingers and log every bite, starts to matter.

In my own kitchen, xylitol blends into some recipes almost as well as sugar. Baked goods don’t always brown the same, but for coffee and tea, it pulls its weight. The taste skips some of the bitterness I’ve noticed with stevia and doesn’t come with the metallic aftertaste some artificial sweeteners bring.

Gut Response Has a Role

Now, here comes the less pleasant part. Anyone who’s eaten too many sugar-free mints has probably felt it: a rumbling stomach, sometimes quick sprints to the bathroom. The body absorbs xylitol only partially, and the rest heads to the colon where it draws in water and ferments with gut bacteria. In practical terms, eating a lot of it can leave you feeling bloated or running for the restroom. The FDA notes this in their labeling guidelines, and I’ve learned my own threshold is about a handful of mint candies before discomfort sets in.

Organizing The Facts: Xylitol and Safety

For those with diabetes, the lack of big blood sugar spikes from xylitol is welcome news. Research in the Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition highlights how switching sugar for xylitol can reduce the overall glycemic load of a daily meal plan. Doctors from the American Diabetes Association acknowledge xylitol as a viable alternative sweetener, but they also recommend keeping consumption moderate. Large doses do not serve gut health well.

People with type 2 diabetes sometimes worry about hidden carbs. Xylitol still carries some calories—about 2.4 per gram, less than sugar but not zero. It adds up if you don’t pay attention. The sweetness matches sugar almost one-for-one, which helps control serving size in recipes, compared to erythritol, which needs extra added to reach the same taste.

Looking for Practical Strategies

Swapping every bit of sugar for xylitol doesn’t create a healthy diet by itself. Building a better meal plan means tuning into your body after trying new foods, reading nutrition labels honestly, and talking about options at doctor’s appointments or with a registered dietitian. It may help to keep a food diary for a week or two, noting any changes in digestion or blood sugar readings after meals that include sugar alcohols. That real data can guide what choices fit best.

The science so far lines up with common sense: xylitol offers a reasonable sugar substitute for people living with diabetes, but no one should treat it as an open door to unlimited sweets.

Does xylitol have any side effects?

What Draws People to Xylitol?

People have looked for a good sugar substitute for decades. Xylitol jumped into the spotlight as an answer for those who want to cut sugar, protect teeth, and keep blood sugar steady. This sweetener crops up in everything from chewing gum to keto snack bars. Its taste closely matches table sugar, minus the guilt and blood sugar spikes.

The Gut Doesn’t Always Agree

Most folks enjoy xylitol with no issues, but I’ve seen some rough stomach days after eating too much of it. Chewing a few pieces of gum isn’t a big deal, but large amounts—think sugar-free mints, candies, or baked goods—can land some people in the bathroom. This happens because xylitol is a sugar alcohol; the body can’t fully break it down. Instead, it draws water into the gut and ferments. That’s where the gas, bloating, and cramps start, especially after 30 grams or more in a day.

Research backs up those outsized digestive effects. A double-blind study published in the European Journal of Clinical Nutrition found healthy adults began experiencing loose stools at around 35 grams per day. Everyone’s threshold looks different. Some tolerate a lot; others run into trouble with just a handful of mints. Kids tend to be more sensitive, and parents often notice this first after a day of too much gum or sugar-free treats at a party.

Alternative Sweeteners and Sensitive Groups

Those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may want to think twice before having too much xylitol. For people managing IBS, sugar alcohols—including xylitol— land on the list of FODMAPs, which trigger symptoms for many. Dietitians often suggest limiting these for anyone struggling with gut pain.

On the bright side, xylitol doesn’t spike blood sugar, letting people with diabetes satisfy a sweet tooth with less worry. That said, over-relying on xylitol or any sweetener won’t erase the importance of balanced meals and mindful eating.

Puppies and Pets in Danger

Most adults ask about side effects for humans, but there’s a hidden danger with dogs. Even trace amounts of xylitol can be deadly for dogs—triggering a sharp drop in blood sugar or liver failure. Veterinary reports show poisoning can come from just one or two pieces of gum. Pet owners need to check ingredients on everything—peanut butter, toothpaste, baked goods. Leaving xylitol-packed foods out where dogs can reach them carries big risk.

Smart Choices and Dosage Awareness

As with many ingredients, moderation helps. Food scientists and global health bodies, including the US Food and Drug Administration, recognize xylitol as safe for use, though recommend keeping portions in check. People starting with xylitol should go slow—watch for signs like bloating, cramps, or diarrhea, and adjust. Enjoyment without overdoing leads to fewer regrets.

A varied diet, fewer processed foods, and a look at labels keeps surprises at bay. If you remember to stash your sugar-free gum somewhere above the reach of your pets, watch how much you eat, most people get to enjoy the perks of xylitol without much downside.

Leaning on scientific evidence, direct experience, and public health recommendations, xylitol provides something sweet, with only a few real caveats. For the vast majority, a smart approach means xylitol stays a friend—not a foe.

How is xylitol different from regular sugar?

Comparing Everyday Choices

Sugar feels like a regular part of life. It’s in coffee, desserts, cereal, and nearly every snack aisle. Xylitol sounds a bit more technical, but you’ve likely seen it in gum and “sugar-free” mints. People often ask if it really makes a difference swapping one for the other. From years observing trends—keeping a keen eye on food labels and science—it turns out the differences run deeper than taste.

Blood Sugar and Energy Swings

Traditional sugar—also labeled as sucrose—comes with a fast ride: spike in energy then a crashing low. Many who monitor their blood sugar find these swings uncomfortable, even risky. Xylitol digests differently. Instead of causing sharp ups and downs, it leads to a slow, mild effect on blood sugar levels. Studies from the American Diabetes Association back this up, showing that xylitol barely nudges blood glucose, making it an option for those managing diabetes or pre-diabetes. Swapping sugar for xylitol can mean less worry about those unpredictable surges, more steady focus through the day.

Dental Health: A Surprising Angle

Sugar is notorious for its relationship with cavities. Bacteria feed on it, producing acid that eats away at enamel. Most of us grew up hearing that brush-and-floss mantra from dentists, but sometimes overlooked are simple lifestyle switches. Xylitol changes the playing field. Research from Finnish dental schools points out that mouth bacteria can’t process xylitol. Instead of producing acid, they starve and lose their foothold. I’ve chatted with several dentists and, increasingly, they recommend xylitol-based gum for this reason. Fewer cavities mean less chair time, fewer bills, and less pain—something anyone can appreciate.

Calories and Weight Control

Trying to cut down on calories isn’t just about willpower. A teaspoon of sugar holds about 16 calories, while xylitol offers about 10. Swapping out sugar in drinks and baking reduces the calorie load. Over weeks and months, those savings add up. Several nutritionists I know encourage clients to try xylitol in coffee or homemade muffins as part of weight loss plans. The taste is sweet enough to satisfy cravings without the usual calorie penalty. It’s not a magic bullet, but every little shift counts.

Digestive Differences and Real-Life Considerations

Not everything about xylitol is rosy. Eat too much and your stomach might complain—cramps or gas can show up if you go far beyond recommended amounts. Based on both personal and client stories, easing in slowly works best. Many packaged products lay out serving suggestions for this reason. Kids and pets especially should be kept away—xylitol is highly toxic to dogs, even in small amounts, which vet clinics know all too well.

Solutions for Everyday Shopping

Choosing between xylitol and sugar comes down to goals. Swapping sugar for xylitol in some foods gives a chance at healthier teeth, stable energy, and smoother calorie control. For families with dogs, extra care with storage and labels matters a lot. More companies offer xylitol in bulk, making it easy to experiment in baking or drinks. For those with a sweet tooth, finding balance takes a little trial and error, backed up by experience, science, and some honest kitchen taste-tests.

Is xylitol safe for pets?

The Real Risk Hiding in Sweets and Snacks

Xylitol sneaks into so many foods and products these days. Chewing gum, sugar-free candies, some peanut butters, even toothpaste. It boosts flavor, keeps calories down, and doesn’t wreck our teeth the way sugar does. If you have pets, though, this sweet deal can turn sour fast. Xylitol and animals—especially dogs—do not mix, and it’s a problem more folks are learning about the hard way.

What Makes Xylitol Dangerous for Dogs?

Dogs process xylitol differently from people. As little as half a gram can send their blood sugar plummeting. The pancreas floods their bodies with insulin, and within minutes, a dog can stagger, vomit, or even have seizures. In some cases, the liver shuts down and there’s no coming back from that. Science backs up the danger: the American Veterinary Medical Association and the FDA both warn about xylitol's rapid, devastating effects in pets.

I have seen the aftermath when a dog finds a purse left on the ground at a friend’s house. A few minutes of nosing around led him straight to sugar-free gum, and an emergency trip to the vet followed. It was a close call, with collective relief when bloodwork came back clear after two days of IV fluids. Not everyone gets that lucky. Dozens of dogs each year die because their owners had no idea this ordinary sweetener would act like poison.

Cats and Other Pets: Is Xylitol a Risk?

You hear less about cats because they don't tend to eat things like gum or sweet foods. Most cats don’t even recognize sweet flavors as “food.” But some treats, dental products, or supplements meant for animals might contain it—so vigilance remains important. No one should assume xylitol’s effects stop with dogs, though dogs show the highest rate of reported poisonings.

Look at What’s in Your Home

Family snacks, supplements, baked goods—read those ingredient lists. Manufacturers often change formulas, sneaking xylitol into all sorts of goodies. If you keep dogs, store items with xylitol well out of reach, preferably in closed cabinets. Pet-safe peanut butter exists, but check every label every time. Some emergencies begin when people give dogs a spoonful of peanut butter, not realizing what’s inside.

Raising Awareness and Finding Safer Alternatives

This problem needs more eyes. Many pet owners learn about xylitol after a scare, but it doesn't have to be that way. Vets across the country are educating their communities, and advocacy groups push for clearer warnings on packaging. Some stores now place signs in the baking aisle or by pet wipes, alerting shoppers to think twice before buying.

Alternatives like honey or fruit purees give sweetness without putting pets in harm’s way. For households with both kids and animals, natural sugars or pet-specific treats are a safer bet. People don’t have to give up the convenience of sugar substitutes entirely, but awareness saves lives. The simple step of keeping xylitol out of paws' reach or skipping it in pet households can mean the world. Nothing ruins a good day quite like a preventable emergency, and no one wants to face regret over the loss of a loyal friend.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2R,3r,4S)-pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol |

| Other names |

birch sugar wood sugar xylite E967 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈzaɪ.lɪ.tɒl/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2R,3r,4S)-pentane-1,2,3,4,5-pentol |

| Other names |

Birch sugar Xylit E967 D-xylitol Pentaerythritol Wood sugar |

| Pronunciation | /ˈzaɪ.lɪ.tɒl/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 87-99-0 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1723203 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9679 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL452 |

| ChemSpider | 5370110 |

| DrugBank | DB11145 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 14e7233b-19a8-4086-b3ed-ec6d925d03ef |

| EC Number | E967 |

| Gmelin Reference | 25994 |

| KEGG | C00794 |

| MeSH | D020123 |

| PubChem CID | 6912 |

| RTECS number | KN7796000 |

| UNII | VCQ006KQ1E |

| UN number | UN 1760 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4021554 |

| CAS Number | 87-99-0 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3593931 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9667 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL414 |

| ChemSpider | 6912 |

| DrugBank | DB11106 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 030000002045 |

| EC Number | EC 200-418-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 2066 |

| KEGG | C00794 |

| MeSH | D013821 |

| PubChem CID | 6912 |

| RTECS number | LU5425000 |

| UNII | VG6YKWG8YQ |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2020917 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C5H12O5 |

| Molar mass | 152.15 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.52 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 642 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.49 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: <0.01 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa ≈ 13.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.95 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -8.2×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.521 |

| Viscosity | Viscosity: 120 cP (25°C) |

| Dipole moment | 4.93 D |

| Chemical formula | C5H12O5 |

| Molar mass | 152.15 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.52 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| log P | -2.49 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: <0.01 mmHg (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 14.48 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.29 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | χ = -9.8 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.521 |

| Viscosity | Viscous |

| Dipole moment | 4.83 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 308.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1207.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2421 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 259.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1208.6 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2434 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A01AD11 |

| ATC code | A07AX01 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed; may cause gastrointestinal discomfort. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319, P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | No hazard statements. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. If swallowed, seek medical advice immediately. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 204 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 410 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): 12,650 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Xylitol: 10,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WN4725000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 g |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed; may cause digestive upset; toxic to dogs. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | Acute toxicity, Eye irritation, Specific target organ toxicity (single exposure) |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep out of reach of children. If swallowed, seek medical advice. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid contact with eyes. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 250 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | > 437 °C (819 °F; 710 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): 12,650 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Xylitol is 16,500 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WFN255 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 2.5–10 g per day |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Ribitol Arabitol Erythritol Threitol Mannitol Sorbitol |

| Related compounds |

Ribitol Arabitol Mannitol Sorbitol Erythritol |