Vanillin: A Deep Dive into Its Legacy and Future

Historical Development

The story of vanillin has roots stretching back to the early 19th century. Long before anyone pulled it out of a lab, vanilla beans flavored everything from traditional drinks in Central America to European desserts. Things changed in 1858, when Nicolas-Theodore Gobley isolated vanillin as the primary compound behind vanilla’s signature taste. The breakthrough in 1874, when chemists Wilhelm Haarmann and Ferdinand Tiemann synthesized vanillin from coniferin, flipped the vanilla market. Suddenly, people didn’t need the slow, expensive vanilla orchid to access that familiar flavor. Industries saw the door open: extraction labs began to replace farmlands, and bakers welcomed a stable, dependable supply. Vanillin gradually shifted from a rare botanical treasure to an everyday ingredient, and its journey reflects a broader pattern in how food production embraces chemistry to stretch thin resources.

Product Overview

Vanillin wears a few faces. In most grocery stores, what customers find labeled “vanilla flavor” actually contains synthetic vanillin, not extracts from vanilla pods. This crystalline powder or clear liquid packs a punch; a small amount floods ice cream, chocolate, or baked goods with a familiar warmth. Beyond sweets, vanillin sneaks into perfumes and even pharmaceuticals, its inviting aroma masking bitterness and helping with stability. Manufacturers source their supply from places like guaiacol or lignin, a byproduct of the paper industry, though natural extraction from vanilla beans continues for premium or niche markets. The variety of production routes means the market offers grades tailored for food, fragrance, or scientific research — each adjusted for purity, strength, and residual compounds.

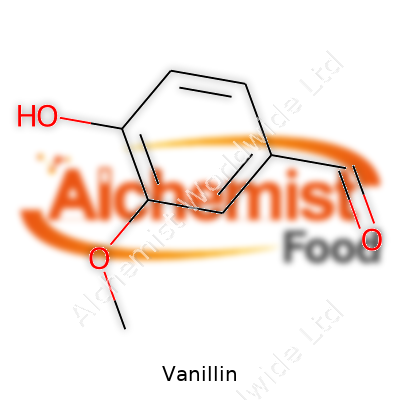

Physical & Chemical Properties

Vanillin stands out as a slightly yellowish crystal, sporting a melting point near 81 to 83°C and boiling at about 285°C. That unmistakable aroma comes from its simple chemical makeup: C8H8O3, with an aldehyde group and two oxygens swinging from a benzene ring. The molecule proves fairly stable, dissolving well in alcohol and hot water but not in cold liquids. Its light sensitivity and oxidation risks demand careful storage. Anyone who’s tried to scoop it from a container knows the fine powder loves to cling, and its intense scent can drift across a room in minutes. This compound owes much of its sensory power to those molecular quirks, explaining both its allure and its widespread use in food and beyond.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Any batch of vanillin intended for commerce comes with stringent standards. Purity usually exceeds 99%, with limits on trace metals, moisture content, and volatile impurities. Food-grade vanillin must pass rigorous reviews to check safety, allergens, and potential contaminants. In labeling, European food regulations list vanillin as E1519, while US markets acknowledge it as a generally recognized as safe (GRAS) food additive. Labels differentiate synthetic from natural vanillin clearly: “vanilla extract” always comes from the bean, while “artificial vanilla flavor” signals a lab-made version. Chemical suppliers note batch number, molecular formula, purity level, and recommended storage conditions, all ensuring quality, traceability, and regulatory compliance.

Preparation Method

The path to a kilogram of commercial vanillin usually starts with guaiacol, a phenol derived from petrochemical or wood sources. Through a methylation step, the guaiacol turns into veratrole, which then finds an aldehyde group through oxidation. This approach, inexpensive and reliable, supports global demand. Paper mills join the story, too, because the lignin leftover from wood pulping breaks down into ferulic acid, which enzymes coax into vanillin. Though more sustainable, that method runs higher costs and complex separation. Natural extraction still remains on the pricey side, reserved for gourmet foods. Researchers in the last decade started exploring biotech fermentation methods, using engineered microbes to churn out vanillin from renewable feedstocks, giving a glimpse into more climate-aware production.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Many chemists look at vanillin as a building block for other molecules. Its exposed aldehyde group opens doors for condensation reactions, including making Schiff bases or reducing to vanillyl alcohol. Seeing vanillin amid fragrances, polymers, or even certain pharmaceuticals, one starts with the same basic compound. Modifications create analogues with subtle scent differences or tweak solubility for better blending. Through careful hydrogenation, researchers filter out new flavors, while oxidation produces vanillic acid — a component with growing interest in antioxidants and health products. Its benzylic position attracts enzymes and catalysts, driving innovation in fine-tuning both structure and performance for niche applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

Vanillin appears on chemical catalogs as 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde. Food and fragrance companies list it as methyl vanillin for clarity. Across languages, names like “vanilline” or “vanilina” crop up. Some markets brand natural-sourced vanillin differently from synthetic, using tags like “Natural Vanilla Flavor” versus “Vanillin (Artificial).” Common product trade names often play on the vanilla connection, aiming for strong consumer association with familiar scents rather than lab origins.

Safety & Operational Standards

Manufacturers and end-users both carry responsibilities when handling vanillin. While safe at concentrations typical for foods, the raw powder irritates skin, eyes, and lungs if mishandled. Facilities list vanillin under low-toxicity substances but still demand gloves, goggles, and fume hoods for daily use. Storage containers must stay sealed, dry, and shaded to prevent spoiled product. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EFSA review exposure limits and use cases periodically, ensuring practices reflect the latest health data. Safety Data Sheets guide every step from receipt to disposal. The rush for “clean label” products led to stricter purity monitoring and trace detection of side products, particularly with biobased routes now entering the mainstream.

Application Area

Few flavor molecules rival vanillin’s reach. Walk into any supermarket and you’ll spot it in everything from ice cream tubs to chewing gum. Bakers and candy makers use it to enhance sweetness or fill the gap left by less flavor-packed ingredients. Perfumers blend it with musks and florals to balance top and base notes, while pharmaceutical labs find it masks the bitter taste of cough syrups and lozenges. Cosmetic folks value its low irritation for soaps and creams, and animal feed producers slip it in to boost palatability for livestock. In the lab, vanillin acts as a reagent and even a marker in thin-layer chromatography, proving once again how a tiny molecule can play a big role in so many corners of daily life.

Research & Development

Recent R&D on vanillin focuses on new ways to make it, reduce waste, and unlock added value. Scientists work with engineered yeast or bacteria that transform cheap sugars or even food waste into the finished product, freeing up chemicals and cutting down environmental stress. Teams have mapped the biosynthesis path in vanilla orchids, hoping for breakthroughs in crop productivity or smarter gene editing. On the material science front, chemists use vanillin as a platform for designing new polymers, antioxidants, or drug molecules. Universities and industrial labs examine ways to recover vanillin from forestry byproducts, promising a closed carbon loop if scaled right. Projects aim for hybrid approaches tying together classic chemistry with green principles, reflecting broader shifts in the chemical sector.

Toxicity Research

Years of study on vanillin’s safety set clear boundaries for its use. Oral toxicity studies in rodents show extremely high thresholds before any harm appears, supporting its standing as a food additive worldwide. Rare allergic reactions turn up in sensitive people, but wide surveys find no lasting accumulative risk when used responsibly. Cell cultures and animal tests check for mutagenic or carcinogenic effects; so far, vanillin passes those screens with ease. Debate continues on impacts from high-purity synthetic versus botanically derived forms, especially with trace contaminants, so ongoing screening matters. Efforts to explore its effect on various microbiomes continue, with early results suggesting limited adverse impact relative to many modern additives. Broad consensus supports daily consumer exposure in levels found in normal diets.

Future Prospects

The vanillin market finds itself at a crossroads. Rising demand for natural food ingredients sparks investment in fermentation-based production. Europe and North America press for eco-friendly sourcing, which boosts the appeal of lignin and agricultural side streams. The global flavor and fragrance industry searches for ways to tweak vanillin’s profile, adjusting blends for developing palates and cultural trends. Bio-based vanillin lures attention not only for its taste, but as a feedstock for “greener” plastics and specialty chemicals. Policy and consumer pressure merge, nudging producers toward transparent supply chains and more sustainable manufacturing. Researchers eye genetic engineering of vanilla orchids and alternative crops, hunting for yield gains or disease resistance. As the lines blur between synthetic, natural, and nature-identical, the debate over how to classify and label vanillin promises both headaches and opportunity. With new tools, tighter rules, and growing demand, vanillin stays at the center of conversations linking food, science, and sustainability.

What is vanillin and how is it different from natural vanilla?

Tasting Memory: The Flavor that Shapes Traditions

Walk into any bakery, and that sweet, comforting aroma likely conjures an instant wave of nostalgia. That warm, inviting smell traces back to a molecule: vanillin. This single compound shapes desserts, perfumes, even cleaning products. Yet, most folks have never really asked, “What’s the difference between vanillin and vanilla?”

How Real Vanilla Gets from Farm to Your Fork

Vanilla comes from the cured pods of the Vanilla planifolia orchid. Growing and harvesting vanilla takes a demanding mix of climate, soil, and patience. Farmers typically hand-pollinate each flower, harvest the green beans, then cure them for months to pull out those complex, inviting flavors. Out of more than 200 flavor compounds in real vanilla, vanillin stands out, but it’s only one character in a much larger cast.

Meet Vanillin: Lab-Made Flavor’s Biggest Star

Most vanilla-flavored items sold today don’t touch a real orchid. Companies rely on vanillin, which they usually synthesize in factories. This molecule has the same chemical structure as the vanillin found in vanilla beans but gets produced on an industrial scale, mostly from petrochemicals like guaiacol, or from lignin in wood pulp.

The advantage? Cost. Vanilla beans cost hundreds of dollars per kilogram, partly because labor and climate swings create unpredictable harvests. Synthetic vanillin costs pennies. That’s why “vanilla” in sodas, candies, and cheap ice creams means “vanillin.”

A Difference You Can Taste—and Smell

Pure vanillin delivers bold, simple sweetness, like a single piano note played loud and clear. Open a jar of real vanilla beans, and you’ll pick up waves of spice, smokiness, floral hints, and something earthy. These extra notes come from dozens of natural compounds built up slowly in the sun during curing. While synthetic vanillin gives sweetness, it lacks the patchwork of flavors and aromas that give real vanilla its personality.

Label Confusion and Trust

Food labels tell another story. “Vanilla flavoring” usually points to synthetic vanillin. “Natural vanilla extract” tells you the producer used real beans. The U.S. FDA sets these labeling rules, yet brands play games—sometimes blending synthetic vanillin with natural extract, sometimes calling out “natural flavors” sourced from rice bran or clove oil.

People often feel shortchanged when they learn that “vanilla” might not involve any pods at all. Label transparency isn’t just a regulatory chore. It’s a matter of trust. Consumers deserve a clear idea of what’s in their food. That trust gets earned by using honest, specific language and making sourcing clear.

Moving Forward: True Choices for Eaters

The food world faces tough choices. Farmers and producers can lean on varietal vanilla, pay locals fairly, and help preserve tropical biodiversity. Food scientists have the tools to create clearer labels and prioritize natural sourcing where possible. Consumers play a part by voting with wallets—choosing real vanilla when possible or understanding what’s behind the bargain.

The story of vanillin and vanilla isn’t about demonizing synthetic flavor. It’s about knowing the difference and giving folks the chance to taste—and value—the full symphony found in genuine vanilla. Recipes, memories, and honest commerce all benefit when nobody’s left guessing about what that familiar flavor truly means.

Is vanillin safe to consume?

Understanding Where Vanillin Comes From

Walk through a baking aisle and the sweet aroma of vanilla hits strong. Most folks think that flavor comes from actual vanilla beans, but lab coats changed that story over a century ago. Today, the key note in just about every common vanilla ice cream and cookie usually comes not from an orchid, but from vanillin, the compound that delivers that iconic vanilla taste.

Pulling real vanilla beans from tropical pods takes months, and costs reflect the work. On the other hand, vanillin—either extracted from wood, or cooked up out of guaiacol (a petrochemical) or lignin—costs much less. Most large food companies rely on this version.

The Science Behind Vanillin’s Safety

Everyday eating brings plenty of chemicals into the body, natural and synthetic alike. I used to worry about every unpronounceable food label, but then I learned more about what makes something “safe” for humans. Agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority have single, clear priorities: keep the food supply from causing harm. Both have stamped vanillin as GRAS—Generally Recognized As Safe.

Digging into the science, vanillin has passed years of scrutiny. Even at much larger doses than any cook or bakery ever adds, animal studies did not turn up toxic effects over the long haul. One rat study, for instance, had to push daily doses equivalent to an adult drinking gallons of vanilla extract for years to find any mild issues, and even then, scientists didn’t see big changes in health. In moderate amounts, the typical sprinkle in ice cream, cakes, or flavored beverages looks safe for nearly everybody.

A Few Caveats and New Questions

That doesn’t mean vanillin deserves zero attention. Chemicals sometimes cause trouble for a sliver of folks, often those with rare allergies or unique genetics. Some people have reported migraines after eating vanillin-heavy foods. Others talk about skin irritation when handling some vanillin-rich cosmetics. These issues seem rare, but it helps to listen if your own body cries foul.

One point crops up in wellness circles: Is natural vanillin from the vanilla bean any better than synthetic? On a molecular level, the two look identical. What changes are the other molecules in the vanilla bean—more than 250 of them—whereas synthetic vanillin singles out the one main flavor note. Some bakers swear by the complexity of real vanilla, while food scientists point out that safety comes down to the main molecule.

Wholesome Eating, Not Just a Single Ingredient

Parents sometimes worry about vanillin in school snacks or birthday party treats. I used to read labels, scan for “artificial flavor,” and fret about every molecule. Turns out, moderation and variety say more about food safety than any single word in the ingredients line. Modern diets need real variety—plenty of fruits, veggies, different grains, nuts, and yes, the occasional treat. Vanillin itself adds flavor, not calories, not extra sugar, and no dangerous residue.

Looking Forward

The safety of vanillin relies on decades of research and continual monitoring by both government agencies and independent scientists. If a pattern of harm showed up, especially among kids or groups with special risks, news would move fast and guidelines would change. For now, a scoop of vanilla ice cream in summer shadows brings simple pleasure, not a safety scare. If you wrestle with food decisions, keep the focus on the big picture: food variety, fresh ingredients, and awareness of your own unique body.

What are the main uses of vanillin in food products?

Vanillin in Everyday Treats

Vanillin brings comfort to kitchens all over the world. The scent of vanilla ice cream, cookies cooling on a tray, or a splash of extract in coffee owes a lot to this one molecule. Most food manufacturers turn to synthetic vanillin these days because natural vanilla beans are expensive and tough to grow. That shift hasn’t decreased demand; in fact, it’s the opposite. Synthetic vanillin helps keep flavored products affordable and accessible year-round.

Satisfying Cravings without Emptying Pockets

Real vanilla demands patience. Climate swings, crop disease, and high labor costs drive up prices. On the other side, vanillin gives bakers a shortcut—capturing the taste and smell most of us expect from anything labeled "vanilla." Cakes, pastries, ice creams, yogurts, and even flavored protein shakes depend on vanillin to add depth that sugar alone can’t provide. At home, I budget for groceries by buying vanilla-flavored, not vanilla bean, yogurts. That’s vanillin working behind the scenes so families can enjoy familiar tastes for less.

Masking Off-Notes in Processed Foods

Food science isn’t only about pleasing the nose. Processed foods sometimes come with metallic aftertastes or dull flavors from preservatives or protein fortification. I’ve sampled plant-based protein bars that would taste chalky and flat without some sweetness and a strong, familiar note—often supplied by vanillin blended into the recipe. A spoonful of vanillin can mellow bitterness in chocolate and balance acidity in sodas. With plant-based products booming, vanillin plays a bigger role than ever in rounding out flavors.

Supporting Lower Sugar Formulas

People care more about sugar content now than ever before. I pay attention, too, watching my own intake for health reasons. Brands use vanillin to trick our taste buds into thinking a product is sweeter than it actually is. Low-sugar cereals, protein powders, and even frostings rely on this subtle sleight of hand. One study found that adding a hint of vanillin lets dessert makers cut up to 25% of the sugar without losing appeal. That small change pays off for those managing diabetes or looking to cut empty calories.

Boosting Perceived Quality

A subtle vanilla aroma also signals "premium" to shoppers. Food companies sometimes pump up the scent of dairy products, chocolates, or baked goods with carefully measured doses of vanillin. Walking through the bakery aisle, it’s hard not to be pulled over by the smell of vanilla. A whiff of vanillin can nudge buyers toward choosing one snack over another. My own kids head for vanilla-scented cakes at birthday parties, and market research backs up that pull.

Finding Safer and Greener Sources

Traditional vanillin mainly comes from petrochemicals, but there’s a strong push for greener ways to make it. Companies extract it from rice bran, wood, and even recycled food waste. Sustainability claims matter, and I see more brands touting “natural” vanillin on labels. This trend supports responsible sourcing and transparency, both important for consumers, nutritionists, and food safety experts. It’s not just a marketing ploy; trusted supply chains improve product safety and support environmental goals.

Looking Ahead

Vanillin’s story follows what people want—to eat familiar favorites, keep costs manageable, and try new foods that still taste good. It helps bridge the gap between tradition and convenience, and opens doors for healthier recipes. For all the modern trends in food, a spoonful of vanilla flavor, straight or synthetic, still makes life a little sweeter.

Is vanillin synthetic or naturally derived?

The Vanilla Story Most People Never Hear

Open up the pantry and there’s always a bottle of vanilla extract. Most people stir it into cakes, puddings, and coffee, never thinking twice about its journey. That warm, familiar scent comes from vanillin. Some folks ask: is vanillin synthetic or does it mainly come from nature? I spent twenty years in restaurant kitchens, and the answer to this question shapes everything from flavor to price.

The Tiny Orchid with the Heavy Lift

Every natural vanilla bean grows from the Vanilla planifolia orchid, native to Mexico but now cultivated worldwide. Growing these beans takes patience. Each flower blooms for one single day—farmers have to pollinate by hand. Beans ripen, then cure for months. From all that work, vanillin forms inside the pod. Natural vanilla carries over 200 flavor compounds, led by the signature taste of vanillin itself. Stick your nose in a jar of beans—there’s no match for the aroma.

Why Synthetic Vanillin Rose to the Top

Global demand for vanilla flavor completely outpaces the amount real beans provide. Over 90% of vanillin used in food and fragrance today comes from something other than the vanilla orchid. Laboratory production began more than a century ago. Wood pulp, cloves, and even petrochemicals step up to supply synthetic vanillin. In truth, almost every ice cream, cookie, or soft drink with “vanilla” on the label gets its punch from lab-derived vanillin. It’s efficient and costs far less.

What’s in the Bottle?

Look at a bottle labeled “pure vanilla extract,” and it likely contains natural vanillin—along with those many other pod-born flavors. Anything called “vanillin” alone, especially if listed separately from vanilla extract on an ingredient list, comes from a synthetic or “nature identical” source. The two smell and taste nearly alike, but natural vanilla offers a complexity that synthetic vanillin can’t fully copy. I used to do side-by-side tastings in the pastry kitchen; the real stuff was deep while the artificial versions gave a straightforward sweetness, sharp but one-dimensional.

Sourcing and Global Impact

Synthetic production keeps vanilla flavors affordable. It also steadies supply, shielding food producers from the wild price swings and crop failures that hit small vanilla farms, especially in Madagascar. Yet there’s a downside. Intensive synthetic production can create environmental problems, especially from wood pulp and petrochemical waste. On the other hand, vanilla grown for extract supports small-scale farmers, giving them a reason to preserve local forests and biodiversity.

Health and Transparency

Both forms of vanillin are considered safe to eat. Still, some consumers want transparency. Food labels rarely explain where vanillin came from, so people concerned about natural ingredients, sustainability, or supporting small agriculture have to dig deeper. Pushing brands for clearer sourcing helps—some now market vanilla with origin stories and details right on the package. My experience? Guests cared as soon as the story landed on the table.

Future Directions

Researchers now work with biotechnology to turn microbes like yeast into vanilla factories, using sugar as a starting point. This approach could cut waste and energy use. There’s hope for blends, too—using a little real vanilla mixed with synthetic to improve both flavor and price. As tastes shift and knowledge grows, more people might demand both great vanilla flavor and a fair shake for farmers and the environment.

Does vanillin cause allergies or have any side effects?

The Story Behind Vanillin

That familiar sweet scent rising from fresh-baked cookies usually comes from vanillin. It’s the main flavor compound in vanilla beans and, for more than a century, the food industry has produced it synthetically to satisfy the world’s craving for vanilla. Most of the vanillin we eat doesn’t come from vanilla orchids but from a lab, using guaiacol or lignin as a base. With so much of it added to food, drinks, and even cosmetics, curiosity about vanillin’s safety makes sense. After all, it winds up on our tongues, skin, and in the air.

Allergy Talk: Fact or Hype?

I’ve met people who swear they react to vanilla-flavored products. Some blame vanillin, convinced it triggers sneezing, rashes, or an upset stomach. The allergy conversation deserves honesty: actual vanillin allergies are rare. Reports in scientific literature back this up; vanillin doesn’t show up as a common allergen the way peanuts or shellfish do. Most people eat or smell products rich in vanillin without trouble. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration considers vanillin “generally recognized as safe,” a standard grounded in decades of research and monitoring.

Yet, “rare” doesn’t mean “never.” Isolated cases pop up: someone getting a rash after handling pure vanillin powder, for example. Sometimes, people with scent sensitivities report headaches, but pinpointing one compound as the cause can be slippery business. Vanillin is usually present in such small amounts it doesn't disrupt normal routines. If someone does notice symptoms, it’s best to check with a healthcare professional, especially for folks with multiple food allergies or a history of contact dermatitis.

Beyond Allergies: Side Effects and Big Doses

For the vast majority, eating cookies or ice cream with added vanillin won’t cause any drama. Problems arise mainly from what scientists call “heroic” doses—amounts far more than anyone gets from food. Animal studies show mega-doses of vanillin can lead to liver issues or upset stomach. In humans, these amounts would never show up in a regular diet. A candy bar or mug of cocoa just won’t deliver grams of vanillin at once.

At work, I’ve handled vanillin for both culinary projects and science demos. Spilling pure powder on my hands left a persistent smell but never caused irritation or hives. That said, no chemical ingredient—natural or synthetic—is risk-free in infinite quantity. The context always matters. Even water can be dangerous if someone drinks too much all at once.

Supporting Consumer Confidence

Trust matters. Consumers want to know what’s in their food and how it affects them. Instead of vague assurances, food companies and regulators need clear labeling and real research. The vanilla flavor industry can do more to track and share any complaints or symptoms tied to vanillin. Quick, transparent investigation earns public confidence. Reporting systems for food allergies and intolerances help scientists and public health teams stay alert for new patterns.

For those with unique sensitivities, reading ingredient lists still counts. Pure bean vanilla extract can substitute for synthetic vanillin if someone feels more comfortable that way. Food scientists constantly work to make flavorings both delicious and safe, but nothing beats honest communication with consumers. People deserve to enjoy their favorite flavors without guesswork or worry.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde |

| Other names |

Vanilla artificial flavoring 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde Vanillaldehyde Methyl protocatechuic aldehyde |

| Pronunciation | /vəˈnɪlɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde |

| Other names |

Methyl vanillin Vanillic aldehyde p-Vanillin 3-Methoxy-4-hydroxybenzaldehyde Ortovanillin |

| Pronunciation | /ˈvænɪlɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 121-33-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/data/structures/models/C8H8O3/Vanillin/3d/Vanillin.jmol` |

| Beilstein Reference | 359354 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:18344 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL502 |

| ChemSpider | 547 |

| DrugBank | DB09462 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.424 |

| EC Number | 4.1.2.40 |

| Gmelin Reference | 8496 |

| KEGG | C00788 |

| MeSH | D014634 |

| PubChem CID | 1183 |

| RTECS number | YO8400000 |

| UNII | 10J9OL5456 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 121-33-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/3d/chebi.chebiId=CHEBI:18345` |

| Beilstein Reference | 359378 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:18344 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL418 |

| ChemSpider | 5799 |

| DrugBank | DB06636 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.017.367 |

| EC Number | 2.1.1.233 |

| Gmelin Reference | 10365 |

| KEGG | C3844 |

| MeSH | D014638 |

| PubChem CID | 1183 |

| RTECS number | YO8400000 |

| UNII | 3J7BU4JVZ5 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C8H8O3 |

| Molar mass | 152.15 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to pale yellow crystalline powder |

| Odor | vanilla |

| Density | 1.06 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 10 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | 1.21 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.011 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 7.4 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 14.4 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -7.6×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.553 |

| Viscosity | 2.37 mPa·s (25 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.70 D |

| Chemical formula | C8H8O3 |

| Molar mass | 152.15 g/mol |

| Appearance | White to slightly yellow crystals or crystalline powder |

| Odor | Vanilla-like |

| Density | 1.06 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Moderately soluble |

| log P | 1.21 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.00133 hPa (25 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 7.4 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.38 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -7.41·10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.553 |

| Viscosity | 2.37 mPa·s (25 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 2.75 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 130.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -504.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3236 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 122.7 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -504.3 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −2990 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A01AD11 |

| ATC code | A01AD11 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | **GHS labelling of Vanillin:** "GHS07, Warning, H302, H317, P264, P270, P301+P312, P280, P272, P501 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements for Vanillin: `"May cause an allergic skin reaction."` |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P272, P302+P352, P321, P363, P333+P313, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 1, Flammability: 1, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Flash point | 158.0 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 530 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not found |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 1,580 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) for Vanillin: 1580 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | WF3325000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Vanillin is "10 mg/m3 (total dust) as an 8-hour TWA (OSHA)". |

| REL (Recommended) | ADI 0-10 mg/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye irritation, may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS irrit. 2, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H317: May cause an allergic skin reaction. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P272, P273, P301+P312, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P321, P330, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362+P364 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | 147°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 530 °C |

| Explosive limits | 1.4–7.8% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 1580 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 1580 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | WFY215000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 104 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Ethylvanillin Isovanillin Acetovanillone Vanillic acid Guaiacol Syringaldehyde Homovanillic acid |

| Related compounds |

Homovanillin Acetovanillone Ethylvanillin Isoeugenol Guaiacol Syringaldehyde |