Urea: A Deep Dive into Its Past, Present, and Future

Historical Development

Stories about fertilizers often start in the soil, but urea’s journey began in a laboratory. Back in 1828, Friedrich Wöhler, a German chemist, stunned the science world by making urea from nothing more than inorganic chemicals. Before this, the common wisdom said you could only get organic compounds from living things. Wöhler showed it wasn’t true, giving birth to the idea that chemistry didn’t stop at the boundaries of life. Since then, the nitrogen cycle—nature’s age-old process—has relied more and more on this man-made product. Agricultural revolutions in the 20th century, aimed at feeding booming populations, brought urea factories to every corner of the globe. Cheap, potent, and easy to ship, urea became the top dog among nitrogen sources, shaping the way food is grown and pushing up yields everywhere it reached.

Product Overview

Farmers pick urea when they want to boost crops without fuss. White and granular, urea dissolves fast in water and adds a kick of nitrogen right where plants crave it. With nitrogen content close to 46%, it offers more bang for the buck compared to most alternatives. Its low price point makes it attractive not just for big operations but for small family-run farms. Beyond agriculture, urea finds its way into resins, animal feed, plastics, cosmetics, cleaners, and even diesel exhaust treatments. This broad market reach comes from its versatility, a trait built on strong chemical properties and flexible manufacturing.

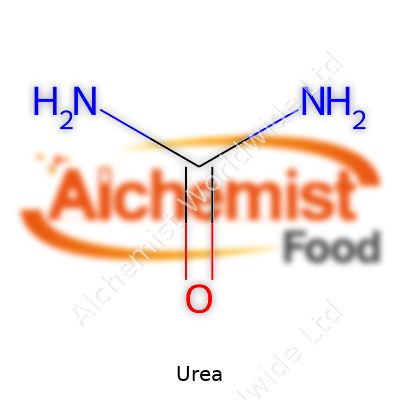

Physical & Chemical Properties

You can pick up urea in the form of small white crystals or granules. It melts at 133°C and isn’t flammable, which makes storage and handling much safer than many other chemicals on the farm. Because it dissolves easily in water, it soaks deep into soil where roots can grab hold of the nitrogen. Urea has the formula CO(NH2)2. The molecule offers two amino groups bonded to a central carbonyl, which means it reacts smoothly with acids and can take part in a slew of chemical pathways. Chemists appreciate its stability at room temperature and its low toxicity in day-to-day usage, though it can break down into ammonia if mishandled.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Walk through a fertilizer warehouse and you’ll spot urea marked with its nitrogen percentage right up front, usually at 46% by weight. Packagers label every sack with purity details, potential contaminants, and batch identifiers to guarantee traceability. Particle size matters for consistent spreading, so most bags show whether the contents are prilled or granulated. Regulations in each country also dictate how urea should be labeled, mainly because it can be diverted for explosives if oversight slips. Brand names often pop up alongside generic labeling, but it’s that nitrogen metric and purity numbers that catch a farmer’s eye first.

Preparation Method

Industrial urea starts with two pretty basic ingredients: ammonia and carbon dioxide. These come together under pressure, with heat speeding up the marriage. The process forms ammonium carbamate in an initial step. Let it heat further, and the carbamate dehydrates to form pure urea and water. Modern plants recycle leftover ammonia and CO2, squeezing out every bit of efficiency they can. Waste management plays a critical role, since small leaks and inefficiencies can add up both economically and environmentally. Equipment must take high temperatures and pressures without corroding, so there’s a steady demand for tough materials and clever engineering at every step.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Beyond the basics, urea reacts well with acids to form urea salts used in specialized industrial processes. Researchers turn to it for making melamine, a key ingredient in strong thermoset plastics and laminates. In medical fields, urea acts as a gentle protein denaturant in lab tests. It also stabilizes proteins and acts as a nitrogen donor in various formulations. If you tweak it through chemical modifications, urea yields slow-release fertilizers, tailored resins, and compounds for specialty coatings. To break down urea in soil, microbes must convert it into ammonia. This natural conversion turns useful in agriculture, but if left unmanaged, it leads to unwanted nitrogen gas emissions and contributes to air or water pollution.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemists know urea as carbamide, a term turning up on medical and industrial product labels. In the world of fertilizers, you’ll see names like prilled urea, granulated urea, and coated urea, each hinting at specific particle shapes or modifications. International trade might refer to it as UN 1350 for transport and safety tracking. Across industries, names shift to signal grade or application, yet nearly all trace back to the same chemical backbone, with tweaks for size, coating, or intended end use.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling urea on the job doesn’t need a chemical engineering degree, but smart safety habits make a difference. Dust from handling may irritate eyes and skin, so gloves and masks rank high on the checklist, especially in bulk storage or mixing areas. Storage calls for dry, well-ventilated settings, since urea pulls in moisture from air and cakes if left open. Regulations cover not only workplace safety but also transport, as high concentrations can feed certain illicit applications. Regular training and clear labeling take the pressure off workers and lower risk levels, building trust and reliability into day-to-day operations.

Application Area

Farmers spread more urea across fields than any other nitrogen fertilizer, using it for cash crops like wheat, rice, and corn. Its fast-dissolving nature fits precision farming and irrigation systems. Livestock industries mix low doses into feed to balance protein costs. In the world of exhaust treatment, selective catalytic reduction (SCR) relies on urea solutions to break down harmful nitrogen oxides from diesel engines, helping heavy-duty trucks and buses run cleaner on busy city roads. Industrial manufacturers weave urea into resins, adhesives, and flame retardants, while cosmetics companies drop small amounts into creams for gentle moisturizing. Hospitals even use urea in topical ointments for treating dry skin or calluses, finding new value in this simple compound each decade.

Research & Development

Scientists continue to stretch what urea can do. In crop science, trials focus on slow-release coatings to curb nitrogen loss and cut pollution. Others hope to create smarter blends that cut greenhouse gas emissions from fields while maintaining yields. Some researchers target bio-based production, using renewable ammonia and CO2 to shrink the product’s carbon footprint. Manufacturers in the plastics and resin industries experiment with purer forms and improved reaction efficiency. Digital tools now help track lost nitrogen in the environment, offering real-time feedback as urea’s performance changes with weather and soil type.

Toxicity Research

Urea scores low on acute toxicity, which means regular exposure at work rarely leads to major health problems, but researchers keep a close watch. Swallowing large amounts can upset metabolism, especially in animals not used to added nitrogen. In the environment, over-application washes urea into waterways, where it can fuel algal blooms and damage aquatic life. Scientists now pay extra attention to chronic exposure and ecosystem effects, worried about added stress on soils and downstream habitats. Factory workers, transport crews, and farmers all face periodic health checks and training, aiming to cut down on mishaps and prevent accidents before they start.

Future Prospects

The coming years promise changes both on and off the field. Food production shows no signs of slowing down, so farmers look to smarter urea blends that stop waste and boost returns at the same time. Environmental pressure prompts agronomists and policymakers to look for tight regulations around runoff and emissions. In industry, urea may gain ground in clean energy and advanced materials, driven by the rush for lighter, stronger plastics and new catalysts. Growing public attention to environmental damage could push organic or bio-based fertilizers, but cost, logistics, and reliability keep urea in the game for now. Smart coatings, digital sensors, and better soil management all point to a future where urea supports more food for more people—without putting the planet at risk.

What is urea used for?

Feeding the World: Urea in Agriculture

Urea belongs on the list of heavy-lifters in modern farming. You’ll see it bagged up in almost every country, helping to grow wheat, corn, and rice. The real reason: urea carries a solid dose of nitrogen, an essential nutrient for plants. You put urea into the soil, and through normal cycles of rain and soil life, its nitrogen feeds crops. Farmers trust it because it works fast, mixes with almost any soil, and costs less than other nitrogen options.

Without urea, getting yields up would cost a lot more. The world’s population keeps growing, yet farmland isn’t expanding much. This makes every square meter of dirt count. A well-timed dose of urea, done right, means a bigger harvest. That’s what keeps food prices in range for many families. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization says nitrogen fertilizers, led by urea, supply much of the world's crop nutrition. This matters when millions rely on staples grown with this help.

Helping Clean Air: Urea in Emissions Control

You wouldn’t expect truck exhaust and farm fertilizer to share a solution, but urea does just that. Diesel vehicles today carry tanks that use a special urea solution called AdBlue or DEF (Diesel Exhaust Fluid). Sprayed into exhaust, it helps break down harmful nitrogen oxides into harmless nitrogen and water vapor. This cuts smog and helps cities breathe a little easier. My old neighbor hauls freight for a living and grumbled about the extra tank at first, but over time he realized city contracts demand clean trucks. Regulations got tighter for a reason: studies point out cleaner air means healthier people.

A 2022 report from the US EPA highlighted that SCR (Selective Catalytic Reduction) systems with urea dropped nitrogen oxide pollution by over 90% compared to untreated exhaust. This progress comes from everyday stuff—urea made mostly from natural gas and air, then packed for transport.

Not Just for Fields and Trucks: Urea in Industry and Medicine

Urea shows up far beyond fields and trucks. Factories use it for resins that show up in furniture, insulation, and plywood. My uncle once ran a small shop gluing veneers on old tables—urea-formaldehyde resin was his go-to for a strong, invisible bond. These glues aren’t fancy, but their strength keeps kitchens and offices together.

Medical labs rely on urea, too. It serves as a safe ingredient in some skin creams, helping with serious dry skin and nail troubles. Hospitals sometimes use it in diagnostic tests, since it plays well with human chemistry and passes out of the body fast. There’s even some use as a feed additive for cattle, helping cows digest certain kinds of grub when pasture grass runs short.

Solving Tomorrow’s Problems

Handling urea isn’t all smooth. Overuse in farming can send excess nitrogen into rivers and lakes, fueling algae blooms that choke fish and stress drinking water supplies. Balancing benefit against risk takes knowledge, careful timing, and sometimes new tech. Precision application, slower-release forms, and farm management education help keep things in check. In transportation, there’s a challenge in keeping quality DEF available, since dirty or fake fluid can damage exhaust systems and release pollution. Regulation and clear labeling do their part, but operators need to stay alert.

From wheat fields and highways to factory floors, urea delivers value. The choices we make around it shape everything from what we eat to the air we breathe.

Is urea safe for plants and agriculture?

A Closer Look at an Everyday Fertilizer

Walk into any farm supplies shop and urea fertilizer lines the shelves. Farmers use it because it’s cheap, plus it packs a punch with more nitrogen than most common options. Plants love nitrogen. They show it in brighter green leaves and faster growth. But urea raises questions, especially about its safety and the bigger picture for agriculture.

Balancing Boosts and Risks

Many who grow crops swear by urea’s quick results. I’ve spread it on fields more than once and watched lackluster corn shoot toward the sky. The science makes sense: plants break down urea into ammonium and take up that nitrogen, fueling leafy growth. Compared to animal manure or compost, urea delivers exactly what growers look for when a crop is looking pale or stunted.

Still, urea is not magic. Sprinkle it on top of the soil and leave it exposed, especially on a hot, windy day, and a good chunk of the nitrogen turns into a gas and floats away. It never reaches the roots. The runoff from a rainstorm can wash nitrogen into streams and ponds, where it feeds toxic algae and pollutes drinking water. That’s not just talk from environmental groups. US Geological Survey data keeps showing spikes in water contamination after heavy fertilizer use in big farming regions.

Safe Doesn’t Mean Foolproof

Used right, urea plays a clear role. Most soils can process and hold moderate amounts. Home gardeners toss it into compost piles to speed up decomposition, or mix a touch into irrigation for a quick pick-me-up. But safe handling means understanding how it works and what can go wrong.

Urea needs moisture and a bit of soil cover to break down before it reaches a plant’s roots. Too much urea piled close to seeds can scorch them. That “burn” comes from high concentrations of ammonia forming as urea breaks down—a familiar sight on fields, where clumps of white fertilizer leave yellow spots. Soil bacteria go to work converting that ammonia, but the process releases other compounds, sometimes acidifying soil over time. Areas relying on urea alone see soil quality slip after a few seasons, especially where land lacks rotation or organic matter.

Smarter Use, Better Results

Safe farming depends on balance and local knowledge. Precision helps: layer urea into the soil, time applications before rain, or use inhibitors that slow nitrogen release. These steps do not just protect crops; they also cut waste and save money. Agriculture research centers worldwide keep testing new mixing methods and organic blends to solve the pollution puzzle. In rice paddies of Southeast Asia, for example, “deep placement” of small urea balls beneath the water reduces loss, requiring less overall fertilizer.

In my experience, the most successful growers talk to their neighbors and experiment in small patches before dosing a whole field. They check their soil, time the fertilizer, and mix sources—using some urea, but not always leaning on it for every need. Even at home, I test soil in my garden, try a handful of urea, and wait before reaching for more.

Moving Toward Sustainable Choices

No fertilizer comes risk-free, especially under changing climate and soil pressures. Urea is widely used for a reason, but its safety depends on how people use it. Training, soil tests, and paying attention to weather all matter. Urea remains an affordable, valuable choice—but not a cure-all for plant growth. Building up soil health with compost, cover crops, and careful rotation always brings better results in the long run.

What is the chemical composition of urea?

Getting to the Heart of Urea’s Chemistry

Urea, known to plenty as a common fertilizer, has a straightforward chemical makeup: it consists of carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and hydrogen. Chemists write its formula as CO(NH2)2. One carbon atom, one oxygen atom, two nitrogen atoms, and four hydrogen atoms connect in a way that delivers big results for food production and industry. My experiences in home gardening and working with local growers have shown just how valuable this simple compound proves to be.

Breaking Down the Structure

Looking closer, urea’s story really starts with its two amino groups (NH2) bonded to a carbonyl group (C=O). These simple groups hold onto each other through relatively stable bonds. The significance lies in how these nitrogen-rich pieces make urea an effective tool for delivering nitrogen to plants. Every bag of urea fertilizer promises 46% nitrogen by weight. That high percentage explains why it sits front and center among nitrogen fertilizers for agriculture worldwide.

Why Chemical Purity Makes a Difference

Contaminants don’t just ruin lab experiments—they create headaches for farmers and folks using urea as a feed additive or manufacturing ingredient. The pure stuff lacks leftover contaminants from production and offers consistent results. During my work in a community garden, we once received a shipment that showed signs of contaminants, probably from careless storage. Crops suffered with burnt leaves and stunted growth. Lesson learned: never ignore what’s in the bag. High purity means fewer worries about heavy metals or unwanted additives sneaking into soil or food, something researchers—like those at the International Fertilizer Association—say directly affects crop safety.

How Urea Gets Made

Manufacturers produce urea by reacting ammonia with carbon dioxide at high pressures and temperatures. These basic ingredients come from natural gas and air. The result is a white, crystalline substance found in 50-kilogram sacks at nearly every farm supply shop. Most people I talk to in the agriculture business pay attention to where and how their urea gets produced. Sustainable production lowers the risk of by-product contamination and reduces environmental impact.

Environmental Impact and Responsible Use

Nitrogen loss poses one of the big issues with fertilizer use. Overuse of urea in fields can translate to nitrate runoff, polluting waterways and harming fish. Having spent summers volunteering on conservation projects, I saw firsthand how algae blooms can blanket rivers and lakes near big farming areas. The culprit often traces back to fertilizer runoff. Getting the most benefit from every grain means matching application rates with crop needs and timing distribution to avoid heavy rains. Research by leading agricultural universities keeps pushing for smarter application strategies and controlled-release versions that help plants without overwhelming the land.

Looking for Solutions

Better management starts with testing the soil. There’s power in knowledge—knowing exactly how much nitrogen sits in the ground makes every application of urea more effective and friendly to the environment. Slow-release coatings and stabilizers have shown real promise and keep more nitrogen in the soil instead of letting it escape into the air or water. Every step forward, from manufacturing improvements to smarter field use, builds on an understanding of urea’s basic chemistry.

In the end, this unassuming compound builds strong harvests, feeds livestock, and supports important industries. Trust in the science and experience behind it ensures that future generations keep reaping the benefits while protecting the land we all depend on.

How should urea be stored and handled?

What Makes Urea So Useful, but Also Tricky

Urea finds a place wherever farmers want lush crops, or truck drivers want lower emissions with AdBlue. Everywhere I’ve seen piles of urea, I’ve noticed folks rarely give thought to where it sits or how they scoop it up. After all, urea looks harmless: just white pellets, easy enough to move and store. Over the years, I’ve seen what goes wrong when people treat it like any old chemical. Trouble starts small—moisture in the air, an open bag, a leaky roof. Then clumps appear, or worse, a powdery mess that’s tricky to handle. I’ve watched costs mount up, not because urea’s expensive, but because waste gets out of hand.

Why Moisture Ruins Urea

Moisture causes urea more grief than most chemicals. It’s hygroscopic, meaning it pulls water from humid air. Leave a bag unsealed, and soon water sneaks in, dissolving the urea just enough to make it sticky or lumpy. I once helped a neighbor open a shed after a wet summer; what should’ve been 10 bags of urea had turned into a single heavy, damp mass glued to the floor.

What does this mean for storage? Dry spaces matter most. Storing urea in a well-ventilated, waterproof building helps keep it dry. Good airflow stops condensation from forming. Anyone piling up more than a few bags ought to use pallets, so moisture doesn’t seep in from the ground. A basic plastic tarp or a moisture-proof liner can go a long way to stop trouble.

Stop Cross-Contamination

On farms, I’ve seen accidents where urea ends up near seeds, animal feed, or even fuels. Feed and seed pick up contaminants, so segregation is key. Never let granules linger on tools or in buckets used for anything edible. I’ve seen two-gallon scoops meant for seed end up full of urea, and that’s a recipe for trouble—both for the next crop or for livestock. Simple solutions work: color-coded scoops, clear labels, and separate storage areas.

Protect Health and Safety

People often ignore safety with materials as familiar as urea. Breathing in dust, though, can irritate the nose and throat. On windy days, dust floats around, and bare hands pick up residue. Gloves and dust masks look fussy, but they make the task more comfortable, especially for anyone with sensitive skin. Eye protection matters more than most realize; dust in eyes leads to rubbing, and rubbing makes things worse.

I remember a friend rushing through a delivery, not bothering with gloves. He ended up washing his hands dozens of times a day from itching, a small reminder that these tiny inconveniences save much more hassle in the long run.

Watch Out for Spills and Waste

Handling urea in bulk opens the door to leaks. Every spill adds up, contributing to waterway pollution. Even a small pile swept into a drain finds its way into streams and rivers, adding nitrogen and risking fish populations. Factory staff and farmers alike do best by handling transfers away from drains or water sources, keeping brooms handy, and treating even small losses as worth attention. A little care, like lining floors with plastic sheeting or using temporary collection trays for spilled granules, keeps usable product on hand and the environment a bit cleaner.

Storing Smart Makes Urea Affordable

For farmers and everyday users alike, low waste means low fertilizer costs and less hassle. Bags sealed tightly after every use, regular checks for leaks on storage bins, and tools cleaned between uses increase the shelf life. Clear signs make the job easier for newcomers and veterans. Folks taking care on the front end avoid headaches later, keep their fields productive, and keep rivers clear.

What are the potential side effects or hazards of using urea?

Everyday Use Meets Real Risks

Urea gets tossed around a lot in fields, gardens, and sometimes even in skin creams. It’s everywhere for a reason—plants gobble up its nitrogen, and manufacturers love the price. But for something so common, a lot of people don’t stop long enough to think about the risks that come with it. Having spent time on both city lawns and family farms, I’ve learned that what seems ordinary can sometimes carry hidden trouble.

Touch Isn’t Always Harmless

Spill urea on your hands, and you may not notice much at first. Some people shrug off skin contact, but after hours out in the summer sun, you can end up with irritation, itchy rashes, or even minor burns. It’s the same story in the garden or large-scale farming: bare hands, then red knuckles by sundown. Eyes get the worst of it—dust can sting badly, and flushing with water suddenly feels urgent. Wearing gloves and safety glasses sounds inconvenient, but it’s no longer an over-reaction if you’ve ever rubbed your eye by accident after spreading fertilizer.

The Air Carries Its Own Warnings

Pour a bag of urea out, and the fine dust floats up. You breathe it in, usually without realizing. This is how sore throats or coughs sneak up at the end of the day for farm workers or backyard hobbyists. Prolonged exposure, especially in closed sheds or storage barns, risks more—headaches, nausea, and sometimes even nosebleeds from the irritation. Dust masks seem like an old-school solution, but they make a difference.

Soil and Water Don’t Bounce Back Instantly

Plants soak up nitrogen, but leftover urea turns into ammonia and nitrates. Too much of this, and the soil pays the price—beneficial microbes die off, water sources collect extra nitrates, and nearby streams start to suffer from algae growth. The famous green scum on ponds? Overuse of nitrogen-based fertilizer, with urea the main suspect. Drinking water with high nitrate levels brings health risks, especially for babies and pregnant women. On my own patch of land, I saw a neighbor’s pond go from clear to soupy in a bad season, all because “a little extra” felt harmless.

How to Keep Out of Trouble

A little planning goes further than most folks think. Gloves, glasses, and dust masks keep immediate problems at bay. On the land, soil testing stands out as a real lifesaver. Too many people spread fertilizer based on a hunch or what’s worked for decades, but test strips or professional analysis actually measure what’s needed versus what’s leftover. After a few years of using test results, I found it saved money and reduced runoff.

Terraces, buffer strips, and cover crops lock extra urea away from streams. Municipal water plants filter a lot, but personal well owners need to keep an eye on groundwater—simple nitrate test kits work fast. The more attention paid to application rates and timing, the less likely you see yellowing leaves, poisoned water, or a red rash that lingers long after the job ends.

The science points to a clear path: respect the product, stay sharp about application, and let common sense trump shortcuts. Urea can help a field thrive or spoil the water table—it all depends on the choices made in the moment.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Carbamide |

| Pronunciation | /juˈriː.ə/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Carbamide |

| Other names |

Carbamide Carbonyl diamide Diaminomethanal Diaminourea |

| Pronunciation | /juˈriː.ə/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 57-13-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | Beilstein Reference: 0733203 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16199 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL472 |

| ChemSpider | 5791 |

| DrugBank | DB03904 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03-2119449126-44-0000 |

| EC Number | 200-315-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: **7156** |

| KEGG | C00086 |

| MeSH | D014510 |

| PubChem CID | 1176 |

| RTECS number | YV4725000 |

| UNII | V1Q0A0IQDW |

| UN number | UN1350 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID9020330 |

| CAS Number | 57-13-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | Beilstein Reference: 0633300 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16199 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL: CHEMBL980 |

| ChemSpider | 518 |

| DrugBank | DB03904 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03fcd3ec-7b1a-4abc-9b14-2e94e18b94e9 |

| EC Number | 200-315-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | 66394 |

| KEGG | C00086 |

| MeSH | D014510 |

| PubChem CID | 1176 |

| RTECS number | YSLA2627600 |

| UNII | FYV47T6045 |

| UN number | UN2071 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | CO(NH2)2 |

| Molar mass | 60.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.32 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 1080 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.11 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: 1 Pa (at 20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 0.10 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.9 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic (-5.6 × 10⁻⁶ cgs) |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.381 |

| Dipole moment | 4.56 D |

| Chemical formula | CH4N2O |

| Molar mass | 60.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.32 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -2.11 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: 0.000044 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 0.10 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.9 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | '-13.9×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol' |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.381 |

| Viscosity | Low |

| Dipole moment | 4.56 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 110.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -333.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -632.2 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 83.3 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -333.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -632.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | M04AB01 |

| ATC code | M04AX02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07; Warning; H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | Autoignition temperature of Urea: 580°C (1076°F) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 8,471 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Urea: 8471 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | RN: 57-13-6 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 46 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown. |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye irritation, may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Exclamation mark |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "No known significant effects or critical hazards. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 454 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 14,300 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 8471 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | PSA60000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 500 mg/kg bw |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

biuret cyanamide thiourea melamine ammonium carbamate |

| Related compounds |

Carbamide peroxide Biuret Ammonium cyanate Guanidine Thiourea |