Succinic Acid: Tracing Its Path from History to Future Uses

Historical Development

Succinic acid came into the spotlight back in the seventeenth century, isolated from amber by distillation. The name “succinic” finds its roots in the Latin word for amber, “succinum.” Early scientists noticed its sour taste and ability to crystallize from water, a curious compound sitting quietly in natural resins and plant tissues. For years, the production leaned on destructive distillation of amber or brown coal, though advances in organic chemistry around the nineteenth century switched things up. Chemists discovered new extraction techniques from fermentation and hydrolysis, turning to barbiturates, specialty polymers, and even early food additives. As science increased demand for precise reagents and bio-based materials, laboratories and industry turned to more efficient fermentation using engineered strains of E. coli and yeast. These methods produce cleaner, more sustainable succinic acid nowadays, aligning with a growing push for greener production.

Product Overview

Succinic acid shows up as a white, odorless solid. Its taste runs moderately sour, not completely out of place among other small organic acids. In bulk, it comes either as glossy crystals or a fine powder, ready for direct dissolution in water. On store shelves, technical grades suit plant growth, animal nutrition, and chemical feedstock work, while food- and pharma-grade lots support everything from pH adjustments in confections to active pharmaceutical ingredient synthesis. People don’t always think of the long chain of compounds that depend on this one small acid—PBS bioplastics, de-icers, agricultural sprays, surfactants, food flavorings, and more.

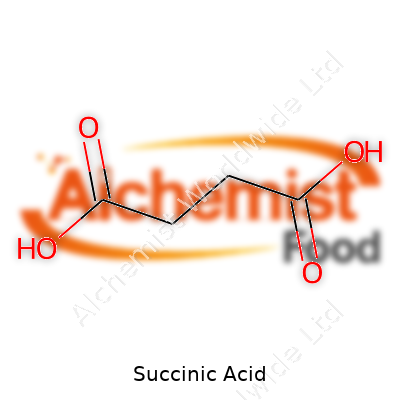

Physical & Chemical Properties

As a dicarboxylic acid (C4H6O4), succinic acid packs two carboxyl groups on a four-carbon backbone. At room temperature, you’ll find melting starts around 185°C, and it boils at over 230°C under a reduced atmosphere. Solubility in water reaches almost 60 grams per liter at 20°C, which proves handy for many industrial recipes. The molecule remains stable under dry, ambient storage, but can slowly pick up water from the air if left uncovered. The acid’s two hydrogens show typical pKa values around 4.2 and 5.6, producing stepwise dissociation in solution. Thanks to this structure, succinic acid works as a buffer in biological experiments, helps chelate metals, and fits as a key building block in polymer chemistry.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labs and plants specify succinic acid based on purity (commercial grades >99%), moisture, color, heavy metal contamination, and fine particle consistency. Certificates of analysis list origin, test results, and batch identifiers, helping researchers match expectations for food, pharma, or technical uses. Proper packaging—airtight, opaque plastics for large bags, sealed tins or HDPE bottles for smaller runs—prevents moisture uptake and keeps the material stable. Labeling rules demand chemical name, CAS number (110-15-6), grade, production date, and hazard indications. Compliance with REACH or FDA regulations also calls for clear tracking from raw inputs to delivered lots.

Preparation Method

Traditionally, coal or amber distillation brought low yields and inconsistent purity, making modern fermentation more attractive. Today, most manufacturers lean into bio-based methods, fermenting renewable carbohydrates like glucose or sucrose. Engineered microbes convert these sugars into succinic acid through tailored metabolic pathways. A typical batch ferments under controlled pH and temperature, bubbling in carbon dioxide and harvesting the acid by precipitation, extraction, and crystallization. Downstream, equipment purifies the acid by solution-phase filtration and washing. Petrochemical processes still operate for certain high-throughput setups, but bioprocessing promises a lower carbon footprint and easier scale-up.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Succinic acid offers two carboxyls ready for a range of reactions. Heat drives dehydration—strip water out, and you get succinic anhydride, a staple for specialty resins, surfactants, and reactive intermediates. Reductions yield 1,4-butanediol, essential in plastics and elastomers. Esterification creates succinate esters: plasticizers, solvents, and softening agents for PVC or foods. Amidation with amines builds links into polyamides and pharmaceutical actives. Oxidizing conditions can break the four-carbon chain, cleaving the molecule for further transformations. The flexibility shown here makes succinic acid more than just another dicarboxylic acid—it’s a gateway to dozens of added-value family members.

Synonyms & Product Names

Trade and common names fill the market: “amber acid,” “butanedioic acid,” and “ethylenesuccinic acid” all refer back to the same core. Systems like IUPAC label it simply as “butanedioic acid.” Some companies market applications under house brands or blended forms, such as growth stimulants for crops branding as “Plant Power Succinates” or technical grades tagged as “SuperPur Succinic Acid.” On lab shelves and industrial catalogs, the chemical shorthand often sticks—SA, SuAc, and similar codes.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling succinic acid doesn’t demand panic, but care sits at the top of any checklist. Eye and respiratory irritation remain possible with dust or concentrated solutions, so basic PPE—goggles, gloves, and a dust mask—keeps troubleshooting headache-free. Storage asks for cool, dry places, sealed containers, and good labeling. Waste streams containing succinic acid can often flow into normal plant effluent after neutralization, but local rules ask for checks on heavy metals or by-products. Environmental impact stays low, with high breakdown rates in soil and water, especially when neutralized by local bacteria and fungi. Workers get the smoothest run by following established standards from OSHA, GHS, and local equivalents, documented through training logs and digital safety data sheets.

Application Area

Farming takes a big slice of the succinic acid pie. Foliar sprays and seed dips benefit both plant health and yield by activating metabolic pathways in stressed or depleted soils. In food, chefs and chemists reach for succinic acid to sharpen flavors in sauces, broths, and candies, taking advantage of its clean, tangy profile. Pharmaceutical companies compound it into anti-inflammatory drugs, migraine therapies, and parenteral solutions, given its biocompatibility and simple renal clearance. Polymer makers turn succinic acid into biodegradable plastics like polybutylene succinate (PBS), shifting the future of shopping bags, packaging, and fishing gear away from petrochemical roots. Water treatment, electroplating, and specialty surfactant blends fill in the gaps, taking advantage of the acid’s ability to buffer, sequester metals, and tailor surface interactions.

Research & Development

Recent years saw huge investment in new microbe strains for green succinic acid production. Some labs work on engineered E. coli that churn out almost 100 grams per liter during high-efficiency fermentations. Others focus on filamentous fungi and tough, acid-tolerant yeasts. Attention goes beyond fermentation—researchers optimize downstream processes, slashing purification costs and turning waste streams into feedstock. Analytical teams invest in better HPLC, mass spectrometry, and titration protocols, hoping to catch impurities or side products before they scale up. Interest doesn’t stop at bio-based routes: catalysis scientists experiment with tandem reactors, hoping to take hydrocarbons directly to acids or select for unique ester patterns. Each improvement drives down cost, energy use, and the chemical’s carbon footprint.

Toxicity Research

Succinic acid slipped into countless foods and supplements, so toxicology data gets plenty of scrutiny. The acid itself breaks down in vivo to intermediates in the natural Krebs cycle, which turns sugars and fats into ATP. Acute toxicity remains low—doses in lab animals reach several grams per kilogram before seeing negative outcomes. Chronic studies look for effects on the gut, kidneys, or liver, and so far, evidence suggests safety at levels found in typical foods. Overuse in supplements rarely reaches the threshold needed for harmful buildup, since the body clears excess quickly in urine. Still, allergy screens and cell assays continue, especially sourcing from new genetically modified strains or complex formulations.

Future Prospects

By 2030, the market for succinic acid keeps climbing, building off consumer love for greener plastics, healthier processed foods, and sustainable agriculture. Big chemical players move production to fermenters powered by waste biomass, tackling both cost and climate criticism. The next generation of PBS-based bioplastics promises stronger materials and compostable packaging, maybe even scaling up to automotive and consumer tech applications. Enzyme engineers work on catalysts to take the molecule into new classes of drug precursors or advanced composites. Researchers in biology look to succinate not just as a raw material, but as a signaling molecule in cancer and metabolic pathways. Governments and trade groups may push for tighter limits on petrochemical versions, nudging buyers toward renewable-sourced stock. With the world calling for more circular, climate-friendly chemistry, succinic acid stands ready to meet a chunk of that demand.

What is succinic acid used for?

The Quiet Star in Industry and Health

Succinic acid doesn’t usually get much press, but it pops up across so many industries that it shapes our daily lives—often without anyone realizing. Back in my early days of trying my hand at home brewing, I stumbled upon its presence in wines and beers, where it gives that pleasant tartness. But it stretches well beyond booze. Over years of research and professional work, I've seen it make its mark in everything from food and medicine to plastics and agriculture.

Food That Tastes Better and Stays Fresher

Ever wondered why some processed foods and drinks taste both tangy and smooth? Succinic acid lifts up flavors in candies, sauces, and wines. Food scientists call on it when they want reliable, natural acidity. Unlike more intense acids, this one balances sour with savory. It also keeps snacks shelf-stable, holding off spoilage a few extra weeks. Given tough supply chains and rising food waste, those extra days matter.

Medicine on a Molecular Level

Doctors and pharmacists don’t have much room for error. Succinic acid serves a quiet role here, too. It gets used in making antibiotics, vitamins (especially vitamin C), and certain anti-inflammatory medicines. Since the body actually produces a small amount of it while turning food into energy, most people tolerate it well. There’s growing interest in its potential to fight fatigue and help recovery, though the research still needs stronger clinical backing.

Plastic That Breaks Down

Pull up just about any new story about plastic pollution, and you’ll see demand for something better. So when chemists figured out they could turn succinic acid into biodegradable plastics, it felt like a breakthrough. Polybutylene succinate (PBS) is one plastic born from succinic acid that returns to the earth much quicker than those old-school water bottles. Switching to plant-based succinic acid, rather than petroleum, is also catching on. Bio-production methods both cut down on carbon emissions and answer consumer calls for cleaner supply chains.

Helping Plants and Animals Grow

Farmers recognize its power, too. Toss a little succinic acid into a fertilizer mix, and stressed crops recover faster during drought or disease. In my own family’s greenhouse, we started using it to keep tomato plants perkier during heat waves. Vets sometimes prescribe it as a supplement for livestock and pets to help with metabolism, especially when animals hit growth milestones or face illness.

What Could Go Wrong? And What Comes Next?

No chemical, even one this useful, escapes scrutiny forever. Overuse in fields can push acidity up and mess with healthy soil microbes. Factory work still produces emissions. Strict guidelines help, but enforcement sometimes lags behind new uses. As the market grows, producers need transparency, strong third-party testing, and workers who understand both the science and the safety precautions.

Making Choices that Matter

Succinic acid may sound simple, but its uses connect to food safety, sustainability, and even medicine. Ensuring people don’t slip into shortcuts—like dumping too much in farms or skipping health checks—keeps this small molecule doing outsized good. For me, each time I see it listed on an ingredient or chemical label, it’s a reminder to ask tough questions and push for smarter production practices.

Is succinic acid safe for skin?

Understanding Succinic Acid in Skincare

Succinic acid’s popping up in more and more skincare products, especially those aimed at people struggling with redness, blemishes, or maskne. It’s a natural compound, found in amber and some sugar cane, but now it also gets produced in labs. The ingredient promises to calm, clarify, and even help with troublesome breakouts.

What Makes Succinic Acid Different

Plenty of folks recognize salicylic acid and benzoyl peroxide from their teenage years, but succinic acid stands apart with a gentler touch. Cosmetic chemists and dermatologists talk about its ability to knock back bad bacteria, which fuels breakouts, without the usual side effects of peeling, strong dryness, or burning. Rather than putting your skin under attack, succinic acid encourages a more balanced environment on the face.

Talking to friends, especially those who struggled with cystic acne, brings out a common concern: almost every harsh product leaves your skin flaky or sensitive. Succinic acid doesn’t seem to follow this pattern. Clinical research backs up those stories—studies published in journals like the International Journal of Cosmetic Science show better tolerance with this ingredient, even on sensitive skin types. It’s often included at low concentrations, around 0.5% to 2%, which helps cut down the risk of irritation.

What the Science Says About Safety

Some folks get anxious around anything labeled “acid,” worried they’ll wake up with a red, angry face. So how does succinic acid measure up? Regulatory bodies including the European Commission have looked at safety data and found no real hazard at the small amounts used in skincare. No evidence ties it to serious allergic reactions, dangerous systemic effects, or long-term health problems in daily use. Allergic contact dermatitis turns up only rarely, and most sources agree it rates low on the list of triggers.

That’s not to say every person gets off scot-free. Some people’s skin reacts to almost anything new, so patch-testing always makes sense. Most dermatologists suggest dabbing a small amount behind the ear or on the inside of your forearm before using it on your face. If redness or itching crops up, it makes sense to stop and check ingredient lists for other common irritants.

Why Succinic Acid Matters for Everyday People

The appeal of succinic acid connects to a broader challenge in skin health: finding something that helps, without making things worse. Social stigma around breakouts and scarring often sends people hunting for stronger chemicals, hoping for quick fixes. My own experience wandering drugstore aisles as a teenager left me with raw, over-exfoliated patches. Customers today crave solutions with a lighter hand.

Succinic acid won’t erase acne overnight, but it forms another option in the toolkit for those seeking relief from mild to moderate pimples, and inflammation. Dermatologists recommend sticking to products from reputable brands, checking for clear concentration labeling, and using sunscreen since acidic products sometimes leave skin more easily irritated by the sun.

Responsible Use and Looking Ahead

More research into long-term use helps everyone, but current information paints a picture of a gentle ingredient that works well with others. For many, succinic acid answers the call for a routine that treats both skin and self-esteem with a bit more kindness. Listening to realistic feedback, patch testing, and talking to professionals before mixing too many active ingredients remains the way forward.

What are the side effects of succinic acid?

People’s Curiosity About Succinic Acid

Succinic acid shows up on more ingredient lists every year. It pops up in skincare routines and in dietary supplements. Food manufacturers use it to control acidity and preserve freshness. Some people even praise it as a natural remedy for aches, stress, and fatigue. This popularity leads many to wonder about safety and what can go wrong if someone takes too much. I’ve noticed in my own circle that few folks check out what side effects this compound might bring, assuming “natural” always means “harmless.” That’s not how biology works, though.

Poking Around Side Effects

For most healthy adults, moderate exposure seems safe enough. The FDA allows it in foods as a flavor enhancer and pH regulator. Safety doesn’t mean risk-free, though. High doses or extended use can set off unwanted symptoms. Some researchers and case reports point to stomach trouble. Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea tend to come up most. Eating something acidic often irritates the gut, and succinic acid is no exception. People with sensitive stomachs or conditions like acid reflux should pay extra attention. If you already struggle with GI problems, tossing new acids into the mix can mean more pain than gain.

There’s another area worth considering: allergies. Rare, but some folks react with hives, itching, or swelling. If your body tends to fight off strangers—meaning new foods, supplements, or skincare products—watch out for warning signs. Just because most users never develop problems doesn’t offer any real guarantees for the next person.

Nervous System and Heart Considerations

Some scientists keep a close eye on the way succinic acid influences the brain and electrical signals in the heart. Animal studies hint that extremely high intakes may tinker with neurological balance, though most supplements won’t come close to those research doses. The worry, in my view, isn’t about daily use of skincare cream or a modest supplement from the health store. The real risk pops up with poor self-medicating habits: people chasing bigger “benefits” by doubling up, thinking more is always better.

There’s early data that suggests too much succinic acid could alter electrolyte levels, with possible knock-on effects for heart rhythms. No one should use this as a reason to panic over a meal or a dab of anti-aging serum, but individuals with kidney or heart issues should keep doctors in the loop before adding anything new.

Managing Risks and Seeking Benefits

Plenty of folks want quick answers. “Is this safe?” isn’t the same question as “Will this cause problems for me?” I’ve found that self-awareness and straight talk with your healthcare team go miles further than trusting marketing. If you’re curious about supplements or want a new skincare routine, study the ingredient list. Check published studies, not just influencers’ opinions. Trustworthy brands will share test results and sources. Stick to recommended dosages.

For those on prescription medications, double-check for interactions. Succinic acid can affect how the body breaks down some drugs, especially those cleared by the kidneys. The most reliable answer comes from talking to a pharmacist or physician who understands your full medical history.

Looking Beyond the Buzz

Plenty of buzz around succinic acid comes from claims that skip over complexity. While side effects don’t hit every person, ignoring them won’t help if you’re the exception. Science and safety both depend on staying aware of the body’s responses. Listen to it. If something feels off, stop. Turn to people with experience or medical training if questions linger.

Is succinic acid natural or synthetic?

Looking at Succinic Acid’s Roots

Succinic acid pops up in plenty of spots once you start looking for it. It comes from plants, animals, and even inside the human body. Some of the earliest chemists found it in amber way back in the 1500s, which explains how the acid got its name. That resin, sticky and gold, held small amounts of succinic acid. Even without fancy labs, people pulled it straight out of tree sap without adding anything artificial or weird.

The Natural Side in Today’s World

These days, nature still handles its share of the heavy lifting. Foods like rhubarb, beets, broccoli, and mushrooms all make a bit of succinic acid on their own. Your body breaks down sugars and starts spinning out small amounts inside every cell. Microbes get busy too, making succinic acid during fermentation, which is useful in winemaking. People have even found it helps give certain wines a smoother, richer taste. No one had to invent succinic acid — it’s just part of how living things run.

Synthetic Succinic Acid Steps In

Fast growth in industries pushes folks to find other ways to make this stuff. For a long stretch, oil and its by-products offered a simple answer. Chemists learned to start with fossil fuels, apply high heat and pressure, and finish with loads of succinic acid at factory scale. This way lets people get large quantities for food flavoring, supplements, biodegradable plastics, and medicine. Sure, it works, but it leans heavy on non-renewable resources. Running with oil leads to extra waste and pollution — the sort of trouble we’re all pretty familiar with these days.

Shifting to Biobased Production

Over the last decade, interest burst open for greener, smarter ways to make things. Succinic acid is no exception. Scientists and startups both started to favor using microorganisms to “brew” succinic acid in tanks — much like brewing beer, just with different microbes and sugars. They feed the bugs sugar from corn, sugarcane, or even food waste, and the microbes turn out succinic acid with much less strain on the environment. It feels a lot closer to how plants and animals do it.

The European Union and the United States Department of Energy both ranked biosuccinic acid in their lists of key “platform chemicals” for sustainable industry. Companies like BioAmber and Reverdia already built huge fermenters to roll out commercial supplies. As the price drops and demand grows, synthetic versions from oil start to lose their hold.

Why the Source Matters

Plenty of people care about where succinic acid comes from — not just scientists or industry insiders. Folks eating clean, organic, or plant-based look for words like “biobased.” Labels rarely share the story of lab versus plant, leading to confusion. Some products market themselves as “natural” just because microbes were involved, while others skip the extra cost and stick with petrochemical origins.

Trusted information starts with easy labeling and true transparency. If someone buys supplements or food, they deserve real facts. Bad labeling damages trust for everyone, from big brands to local growers. Governments set tight rules for what counts as “natural,” but shoppers want proof and honesty. Tools like QR codes can open up sourcing history in a snap. That simple step does more for trust than any buzzword ever could.

Finding the Best Path Forward

Switching from oil-based processes to microbe fermentation gives industries a clean shot at lowering pollution, cutting waste, and keeping more land healthy. Local farmers could sell leftover sugar crops instead of watching them rot. Next time someone reaches for a drink, a snack, or even an eco-friendly plastic toy, the story of succinic acid may stretch back to a greener, more natural path — and everyone benefits when the truth comes out.

How is succinic acid produced?

Ancient Roots, Modern Uses

People started making succinic acid from amber centuries ago. Melt the resin, catch the vapors, cool them off, then scrape up white powder: that was the deal. Today, you’ll run into succinic acid in the plastic of your electronics and the coatings on your pills, far from its woodland heritage. Its rise tracks our appetite for greener chemistry and less oil in the supply chain.

Petrochemicals or Sugar?

Petrochemistry long led the production game. Refiners break down oil and gas into maleic anhydride and then convert it with water into succinic acid. The process has churned out reliable volumes for decades. But these days, growth comes from a different place: biotechnology.

Let’s consider biomanufacturing. Microbes like E. coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum gobble up sugars found in corn, wheat, or sugar beets. In big, carefully controlled vats, they turn the sugars into succinic acid, in effect swapping smokestacks for fermentation tanks. This kind of setup opens new economic doors for towns that may struggle as oil chemistry contracts, using crops or factory leftovers instead of fossil resources.

Sustainability and Local Impact

Chemical plants carry heavy baggage—air pollution, spills, and massive water use. Plant-based microbial production changes that. I know a farmer group in Iowa that started selling their corn silage to a biorefinery. Same fields, but new buyers and more resilient prices. That kind of diversity helps local economies hang on when commodity swings hammer people’s budgets. From a carbon standpoint, fermentation also shrinks footprints. Academic studies, including research funded by the European Union in recent years, measure up to 60% less net carbon emission per kilogram produced. Fewer emissions mean healthier communities and less contribution to climate change.

Technical Hurdles and Progress

The main challenge rests in fermentation yield and downstream purification. Sulfate or phosphate from processing steps often ends up as waste, putting extra work on water treatment plants. Engineers continuously look for cleaner, closed-loop methods. They play with the genetics of the microbes, coaxing them to work faster, chew up more varied feedstocks, and cough up purer product. I spent a summer interning at a pilot-scale biofactory: you learn quickly how fouling or leaks from one line slow the whole process. Getting consistent batches remains tricky, though progress comes year by year.

Thinking Forward: Opportunity and Caution

Brands looking to cut their environmental impact put succinic acid high on their list. Startups and big firms alike sign long-term contracts, betting on it to help them meet carbon goals. That said, food prices matter—production that pivots to non-food waste or agricultural byproducts draws less criticism. In the end, both bio-based and petrochemical versions remain in play. Oil-based approaches can handle wild swings in demand; bio-based fills the niche for “green” markets and growing product lines where brand image means everything.

What stands out to me? It’s the way this scene draws in everyone from synthetic biologists to small-town growers. With work, succinic acid tells a story beyond chemistry—a shot at local jobs, cleaner water, and fresh tech without losing sight of the legacy materials keep.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | butanedioic acid |

| Other names |

Amber acid Butanedioic acid E363 Ethylene succinate Spirit of amber |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsʌk.sɪn.ɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | butanedioic acid |

| Other names |

Amber acid Butanedioic acid E363 Succinicum acidum |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsʌk.sɪ.nɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 110-15-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1718731 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15741 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL679 |

| ChemSpider | 796 |

| DrugBank | DBSucc |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.065 |

| EC Number | 2.4.1.19 |

| Gmelin Reference | 10399 |

| KEGG | C00042 |

| MeSH | D010972 |

| PubChem CID | 1110 |

| RTECS number | WSQ70 |

| UNII | GSE87Y44JJ |

| UN number | UN3261 |

| CAS Number | 110-15-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1208731 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15741 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL681 |

| ChemSpider | 548 |

| DrugBank | DB02709 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 07a41750-c37b-4950-b845-16f7bfae01fd |

| EC Number | 2.4.1.19 |

| Gmelin Reference | 639 |

| KEGG | C00042 |

| MeSH | D010379 |

| PubChem CID | 1110 |

| RTECS number | WSU4371620 |

| UNII | F8FY29JJJS |

| UN number | UN3261 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O4 |

| Molar mass | 118.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.56 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 58 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -0.59 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.1 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.21, 5.64 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.60 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -29.8·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.555 |

| Viscosity | 2.45 mPa·s (at 25 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 4.52 D |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O4 |

| Molar mass | 118.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.57 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 58 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -0.59 |

| Vapor pressure | 1 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.21 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 2.67 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -59.0·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.558 |

| Dipole moment | 4.52 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 156.3 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -907.4 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1466.0 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 157.4 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -909.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1466 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX10 |

| ATC code | A16AA15 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P280, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0-W |

| Flash point | 210 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 450 °C (842 °F; 723 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 2260 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral 2,260 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SNV6000000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 50 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.67 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0-W |

| Flash point | 205°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 440 °C (824 °F; 713 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 2260 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral 2,260 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WF8050000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 50 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 2 g/kg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Oxalic acid Malic acid Fumaric acid Glutaric acid Adipic acid Maleic acid |

| Related compounds |

Malic acid Fumaric acid Maleic acid Glutaric acid Adipic acid Oxalic acid Tartaric acid |