Sorbic Acid: A Hard Look at a Quietly Essential Preservative

Historical Development

Long before preservatives landed on supermarket shelves, food spoilage was a harsh daily reality. People pickled, fermented, salted, or dried what they could, but fresh food never lasted long. Sorbic acid first popped up in 1859, a product of distilling oil from rowan berries. Over decades, chemists picked apart its structure, eventually putting it to work in practical ways. By the 1940s, sorbic acid proved its value as a food preservative. Once commercial production gained momentum, bread, cheese, and canned foods suddenly tasted fresher, sat on shelves longer, and grew less mold.

Product Overview

Sorbic acid sits on ingredient lists just beneath the radar, usually named alongside potassium sorbate. Both guard food and drinks from mold and yeasts. While its origin story starts in plants, today’s batches roll off chemical reactors, holding steady as white, powdery flakes, sometimes in granular form for ease during large-scale production. Each bag of sorbic acid gets used by bakers, cheesemakers, wine bottlers, cosmetics makers, and animal feed producers—really anyone trying to keep microorganisms out and safe shelf life in. Though the name stays the same, sorbic acid tucks into products in ways that most folks never notice.

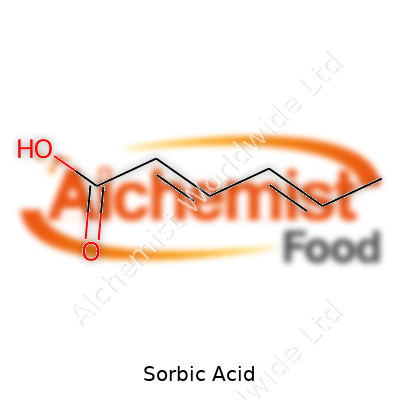

Physical & Chemical Properties

Sorbic acid answers to the chemical formula C6H8O2, showing up as solid, odorless, and with a faintly acidic tang if tasted. Its melting point clocks in at around 135 degrees Celsius, so it won’t drift off on a warm day but dissolves fine in alcohol or fats. Water presents a challenge, where solubility only rises when the temperature does. Shelf stability comes standard—kept dry and cool, sorbic acid barely reacts with air or light, explaining why it stores so well from factory to finished product. Its preservative power builds on its knack for blocking mold and yeast at low concentrations, rarely leaving a chemical taste behind.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers don’t have much wiggle room with food grade sorbic acid. The industry eyes every batch for purity above 99%. Heavy metals can’t creep past low parts per million, and regulators pay particular attention to lead, arsenic, and mercury. Labels mention its E number (E200) across continents, since oversight from bodies like the FDA and EFSA means details and recommended use rates land right on spec sheets or in legal codes. Additive lists require clarity, not just for big factories but for the average consumer trying to decipher ingredients. Researchers testing food safety look at each technical detail—assay, moisture, ash, and residues—to ensure nothing out of line sneaks onto plates.

Preparation Method

No one returns to rowan berries to extract sorbic acid these days; the world relies on synthetic chemistry for speed and scale. Most industrial production pairs crotonaldehyde and ketene in neat chemical reactions, skipping the agricultural middle-man. After reacting and purifying, the process delivers dry, high-purity sorbic acid ready for blending. Companies design reactors for minimal waste and consistent quality, because even small missteps can leave behind impurities that disrupt taste, safety, or chemical action. As demand pushes upward, efficiency and sustainability in manufacturing stay in sharp focus, guiding improvements in process design.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Sorbic acid keeps its chemical head down most of the time, but tweak it with a base and it forms potassium sorbate—a far more water-friendly version used widely for practical reasons. Its structure, marked by conjugated double bonds, gives it bite against fungi but keeps reactivity low with food components. Under harsh conditions or high heat, sorbic acid can break down or shift, creating byproducts that researchers keep an eye on for safety. Some researchers explore further chemical modifications to boost solubility or open up new uses, but the star by far remains the original molecule and its readily transformed salt form.

Synonyms & Product Names

Labels and spec sheets rattle off more than one name—2,4-hexadienoic acid, E200, sorbinsäure in German, or acide sorbique in French. Potassium sorbate, the chief salt, hides as E202. In pharmaceutical circles or industrial catalogs, other names might crop up, but most buyers know what they’re getting with either of these. Language changes, regulations differ, but as long as the sorbic acid meets global standards, its identity remains trusted by manufacturers and inspected by regulators.

Safety & Operational Standards

Most research and regulatory reviews land on the side of safety for sorbic acid, as long as users stay within established limits. Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) in the United States, it receives similar acceptance in Europe and Asia. Food technologists stick to strict maximum allowable doses because creeping above could affect taste or digestive comfort, not to mention raising regulatory red flags. Production lines operate with well-defined cleaning, storage, and handling protocols, since dust and contact with eyes or skin still demand protective equipment and proper ventilation. For workers, routine monitoring minimizes any long-term exposure risk. For consumers, risk remains negligible; the digestive system breaks down small servings without fuss.

Application Area

Those who work with processed cheese notice its absence fast—mold takes over without this preservative. Bakers point to soft, shelf-stable breads and cakes, safe from spoilage for days or even weeks. Wine bottlers swear by its antifungal effect, keeping fermentations predictable and cellars clear from stubborn spoilage. Personal care formulating chemists reach for sorbates as well, protecting lotions and shampoos from the quiet creep of bacteria and mold in humid bathrooms. Animal feed, beverage syrups, fruit snacks, and condiments—most industrial food lines somewhere include sorbic acid or its salts. Its reach doesn’t stop at dinner tables, either; some pharmaceutical products, dental materials, and even paint formulations draw on its technical benefits.

Research & Development

Scientists always push for ways to outsmart spoilage without shifting sensory qualities or luring unwanted attention from consumers wary of chemical names. Ongoing studies look for methods that lower needed concentrations even further, combine sorbic acid with natural antimicrobials, or keep food safer under milder storage conditions. Automation and manufacturing traceability shape modern efforts—companies need to show regulators exactly what enters food and prove clean, repeatable processes. At the same time, researchers keep tabs on new fungal resistance, driven by long-term preservative use, setting industry pulse for future additives and approaches.

Toxicity Research

While decades of work back sorbic acid’s safe use, nutritionists and toxicologists keep at it, judging any sign of hormonal disruption, carcinogenicity, or allergic impact. Most studies agree it passes through the human body quickly, breaking down into harmless metabolites. Animals tested at wildly higher doses than humans would ever ingest show only mild, reversible side effects. Rare cases turn up among sensitive populations who react to sorbate preservatives, but strict dose limits drive the industry standard and regular review by food safety authorities. Watchdogs periodically recommend revisiting Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) levels in light of new data, keeping a cautious but fair outlook.

Future Prospects

As more pressure falls on food companies to cut waste but keep safety tight, sorbic acid stands as one of the most consistent, reliable answers. Research crowds in on green chemistry for sorbate production and alternative blends with natural flavors or bio-preservatives. Tech jumps in manufacturing—better mixing, finer particle sizes, faster dissolution—push the limits of what’s possible in applications where sorbate use was once tricky. Grocery aisles and ingredient orders reflect changing public opinions, but shelf life and safety don’t give up top billing easily. The larger trend follows consumer trust; so long as that stays grounded in facts and solid science, sorbic acid will keep playing its role on production lines, quietly fighting spoilage in the background.

What is sorbic acid used for?

What Makes Sorbic Acid Useful?

Sorbic acid keeps food safe and fresh. Most folks grab a loaf of bread or a pack of sliced cheese from the store and toss it in their cart without thinking about why it won’t mold before next week. Sorbic acid often does the heavy lifting behind the scenes. It stops the growth of mold, yeast, and some bacteria without changing how food tastes or looks. Food companies rely on it, and it shows up in everything from baked goods to fruit juices.

Shelf Life and Consumer Safety

Wasting food stings—on the wallet and the planet. Sorbic acid puts the brakes on spoilage, so foods sit on shelves longer and people throw away less. This helps supermarkets, food makers, and anybody trying to stretch their grocery budget. The safety record stands pretty strong. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives and the European Food Safety Authority both reviewed the science and set limits to keep consumption at safe levels.

Beyond the Kitchen

The story doesn’t end in the snack aisle. Cosmetics and personal care items face many of the same preservation challenges as food. Sorbic acid can keep lotions, creams, and shampoos from turning rancid or developing funky smells. The cosmetic industry trusts this compound for its low chance of irritation and its record of safety. Even in packaging—like wraps for cheese or meats—you’ll find its name tucked inside the ingredients if you take a look.

Skipping the Old Ways: Why It Matters

Salt and vinegar used to be the only ways to keep food from spoiling. But salt-heavy or pickled foods wear thin after a while. Sorbic acid changed the game because it works at much lower concentrations. Instead of drowning bread in preservatives, bakers use small amounts and keep the flavor pure. Without it, manufacturers would have to ramp up refrigeration and shipping costs or return to methods that don't work well for today's busy world.

Health, Perception, and the Demand for Clean Labels

Still, many shoppers scan ingredient lists and hesitate at words they don’t recognize. Some want “clean label” foods, free of chemicals and hard-to-pronounce names. There's a growing push for transparency: people ask where ingredients come from and how they’re tested. Food experts, nutritionists, and consumer advocacy groups dig into published research, looking for risks or side effects. So far, sorbic acid passes those tests. Still, it pays to keep an eye on ongoing studies and new data, especially since eating patterns and health advice change over time.

Room for Improvement

No food additive solves every problem. Some microbes can break down sorbic acid over time, which means it won’t protect forever. There’s also the challenge of finding sustainable sources and making sure production methods align with environmental goals. Focusing on new natural preservatives—like fermented extracts or plant-based compounds—provides another path. Consumers also hold a lot of power by supporting brands that invest in safe and transparent food science.

Looking Forward

Sorbic acid quietly plays a big role in modern life. It defends food and personal care products from spoilage. Better education and open research keep it trustworthy. Responsible use and ongoing study matter, but sorbic acid shows how often the smallest things make the biggest difference in everyday living.

Is sorbic acid safe for consumption?

What Sorbic Acid Does in Our Food

Sorbic acid helps stop spoilage in lots of foods found on store shelves. Big companies and small bakeries both rely on it—think of sandwich bread, shredded cheese, or those little fruit cups in lunchboxes. Anyone who has found mold at the edge of a carton of yogurt understands why food makers use preservatives like this one. Sorbic acid doesn’t add taste or change texture and works quietly in the background, knocking down fungus and bacteria.

Looking at the Research and Regulation

I remember seeing “sorbic acid” or “potassium sorbate” on labels since I was a kid and wondering if I should skip products with such names. Later, I learned that researchers have kept tabs on its safety since the 1940s. Agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority reviewed hundreds of studies. They gave sorbic acid the thumbs-up as safe when used as directed. Typical amounts in baked goods sit around 0.02%—about a pinch per loaf.

No study so far links this ingredient to cancer, genetic changes, or birth defects in people or animals. Sometimes folks with sensitive skin can get rashes from handling it directly, but that won’t happen from food-level use. The body breaks down sorbic acid into water and carbon dioxide, just like a banana or potato. Safety reviews happen every few years. If new red flags turned up, regulators would take action fast—they don’t want repeat cases of chemicals slipping through the cracks.

Misconceptions About Preservatives

Some people believe “preservative” equals “bad” because a few older ones caused problems. That’s fair. But painting all preservatives with the same brush doesn’t make sense with today’s evidence. For example, in my own family, comparisons between homemade bread and store-bought show a big difference in how long they stay fresh. Without something like sorbic acid, bread quickly goes moldy, and all that good food goes to waste. Less food wasted means less strain on wallets and the planet.

Old fears also pop up on social media. I’ve seen claims that sorbic acid “lines the stomach” or “causes headaches.” Large, controlled clinical trials haven’t confirmed any of this. Small studies sometimes spark concern, but scientists look across all available data before making a call. Listening to experts who read those studies can cut through a lot of internet myths.

Smart Choices and Transparency

No food ingredient can be called “risk-free” in every single case. That’s true for strawberries and peanuts, not just things like preservatives. In rare cases, a person might have a sensitivity or want to avoid processed foods for other health reasons. Reading ingredient lists and making choices that fit your own health needs matters. Some brands are upfront about why they use certain ingredients and how much—they even put info on their websites or answer questions directly.

Food scientists keep exploring new ways to knock out spoilage without any additives. In my kitchen, I find that freezing works for homemade bread, and for people who bake often and eat fast, skipping preservatives might be fine, too. For others, especially with big families or long grocery trips, sorbic acid’s safety and reliability win out. Regulatory checks and decades of research back up its everyday use. It pays to stay informed and keep asking questions, but the evidence supports the safety of sorbic acid in our daily diets.

What are the side effects of sorbic acid?

Why Food Makers Use Sorbic Acid

Open your pantry and there’s a good chance you’ll spot sorbic acid listed on the back of a snack package. Sorbic acid isn’t some lab-only mystery, it’s a common preservative made to keep food fresh a lot longer. Mold and yeast love warm, moist conditions—and so do a lot of our favorite foods. That’s where sorbic acid steps in, slowing down those tiny invaders. Success in the supermarket sometimes comes down to shelf life, so you’ll find this compound in bread, cheese, dried fruit, and even drinks.

Side Effects—Sometimes Overlooked

Doctors and regulators see sorbic acid as mostly safe for daily use in food. Years ago, I read stacks of boring ingredient labels, thinking little about preservatives, until my younger sister developed an allergic rash after some store-bought cheese. Turns out, some folks do react to additives like sorbic acid. Most of the time, reactions show up as mild skin irritation or hives. These effects can catch someone off-guard—itchy skin after a meal, or small swelling around the lips and eyes. It’s not usually life-threatening, but it sure isn’t fun to watch spots appear after eating what looks like a harmless meal.

Surveys and safety reviews back this up. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and European Food Safety Authority both greenlight sorbic acid for human consumption, but they warn that a few people with allergies or sensitive skin might have a problem. Clinical cases show children sometimes prove more sensitive than adults. Stores rarely label these products as allergenic, making it tricky for parents trying to pinpoint what’s giving their child a rash.

What Science Says About Ingesting It

Gut trouble sounds like a risk with any food additive. Researchers dove into possible digestive side effects and didn’t turn up much: sorbic acid usually offers a smooth ride through the digestive tract for most. Studies using animals and humans found that the body breaks it down and gets rid of it without drama—unless doses jump far beyond what folks eat in an average diet. The main concerns pop up at very high concentrations that don’t match real-world recipes.

Long-term studies show low risk, even with years of consumption, as long as amounts stay within limits. The World Health Organization picked a daily intake that falls well below what you’d ever eat just by choosing lunch at the cafeteria.

Sensitive Groups and Better Labeling

Some groups stand out as more vulnerable: children, folks with skin problems like eczema, and people with strong food allergies. Tracking which foods bother your body can be tough. I’ve started snapping photos of ingredient panels and making notes after meals, especially when someone in the family reacts. Better ingredient transparency would help everyone—bigger labels and plain language stop people from getting blindsided by hives.

Avoiding sorbic acid isn’t always possible. Cook your own food, and you mostly dodge it, but eating out or grabbing a pre-made meal often means taking your chances. If a reaction shows up, it pays to share details with your doctor and save those product receipts.

What Can Improve Safety?

Producers can do more—clearer labeling and investing in testing for reactions among sensitive groups, especially kids. Parents and schools benefit from easy-to-read allergen notices. Medical practitioners can flag possible sources in patient care, especially with unexplained rashes or stomach problems.

Staying informed turns anyone into a better shopper. Scanning labels, knowing common preservatives, and sharing what you learn with others helps everyone keep risky side effects off their plates.

Is sorbic acid a natural preservative?

What Sorbic Acid Actually Is

Sorbic acid shows up on ingredient lists everywhere—from loaves of bread to shredded cheese. Food makers point to it as a “mild” preservative, helping delay the kind of spoilage everyone tries to avoid. The source of the confusion comes down to where this compound starts and how it lands in the products at the store.

Straight from Nature—or Not?

Here’s an old truth: sorbic acid was discovered in the oil of mountain ash berries. There’s a history there. Early research pulled sorbic acid right from the fruit. That origin probably set the groundwork for its reputation as a “natural” option. In practice, sourcing sorbic acid by squeezing berries wouldn’t work on the scale a modern food manufacturer needs. They use a chemical process involving crotonaldehyde and ketene, turning raw ingredients into the powdery substance found in food labs and factories across the world.

The FDA and European Food Safety Authority both recognize sorbic acid and its salts as safe. Scientists and health professionals agree sorbic acid poses little risk at the concentrations used in food; it breaks down easily in the human body. In fact, sorbic acid’s GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) status has helped fuel its widespread use. It beats out some of the more controversial synthetic preservatives because it doesn’t linger or bioaccumulate.

What “Natural” Really Means in Preservatives

Natural is a word that gets thrown around a lot without clear rules. Most shoppers I know assume it means something close to the farm, or at least close to its original plant or mineral form. Food chemistry doesn’t stick with marketable definitions, though. By the time sorbic acid ends up in production, it looks nothing like the trace amounts in mountain ash berries. This upsets some shoppers. The reality is that nearly all commercially used sorbic acid comes from lab synthesis.

The real story gets shaded in marketing. Some brands use natural-sounding language to soothe consumer doubts. It taps into trust, into the hope that these preservatives mean fewer worries for families and kids. A person working in the bread aisle for twenty years has seen how new labels can cause a sudden shift in which products sell and which gather dust.

How Does This Impact Health and Food Choices?

Sorbic acid stops mold and yeast reliably. Moldy food throws away money and can make people sick, so keeping bread fresh longer matters. Still, people who want to avoid anything synthetic won’t find comfort in technical definitions. In my own kitchen, I feel warier when I can’t trace a food’s ingredients back to a clear, understandable origin.

Transparency gives shoppers a way to make the decisions best for their needs. Full disclosure on the label does more for trust than a big “natural” sticker ever could. The trade-off is always there: less spoilage or cleaner labels. Whole foods without preservatives need to be bought and eaten fast. For working parents, longer shelf life can ease both budgets and schedules.

Better Choices Moving Forward

Building strong habits starts with honest information. Regulators and brands should keep pushing for clear labeling that spells out the source and process of each ingredient. At the same time, more funding for research into preservation techniques could give future shoppers more satisfying options. Whether that means harnessing natural compounds directly from plants or finding new effective methods, better tools come from open science and transparency. Eating well is easier with fewer marketing games and more facts right on the package.

What foods contain sorbic acid?

The Additive That Keeps Snacks Fresh

Sorbic acid may sound mysterious, but it’s just a food preservative. You’ll spot it, or the more common potassium sorbate, by reading the label on breads, cheeses, and some packaged sweets. Food producers have leaned on it for decades because it slows down the growth of mold and certain bacteria without bringing strong flavors. I grew up seeing my grandmother fuss over homemade jelly when sugar alone wasn’t enough to keep fuzz away, but the big commercial jars on supermarket shelves stay mold-free for months, thanks to sorbates.

Why Bakeries and Cheese Counters Keep Sorbic Acid Handy

Sliced bread, tortillas, and hamburger buns often contain sorbic acid. It extends shelf life so that nobody feels sour biting into a sandwich. Soft cheeses like cottage and cream cheese contain it because they spoil fast. Even shredded mozzarella, which clumps easily and attracts moisture, relies on these preservatives to stay usable after opening.

The deli counter stocks tubs of dips—sour cream, guacamole, and processed cheese spreads—that depend on sorbates. Sauces such as ketchup, salad dressings, and mayonnaise feature it too, especially those brands promising weeks or months in the fridge after opening. I remember helping run community potlucks and learning quickly which foods would go off first. The store-bought salad dressings outlasted anything we made ourselves.

Hidden in Fruit, Sweets, and Drinks

Dried fruits like apricots, prunes, and figs owe their endurance to added sorbic acid. It shows up in candied fruit and some fruit roll-ups, letting parents tuck them in lunchboxes without much worry about spoilage. Bakers looking for shelf-friendly pastries use it in cherry pie filling, jams, and frostings. Even that soft snack cake in a shiny wrapper has likely met sorbic acid on its production line.

Low-alcohol drinks—hard cider, mead, some flavored malt beverages—also use potassium sorbate to stop fermentation after bottling, preserving the taste and preventing sour explosions. Fruit syrups, sparkling sodas meant for kids, and even some imported wines include the preservative for stability during storage and shipping.

Why It Matters for Health

Food producers and governments regard sorbic acid as low-risk. The European Food Safety Authority and US FDA both approve sorbic acid and potassium sorbate for many uses. Maximum allowed amounts ensure safety, so the preservative protects food without posing a danger when eaten as part of a balanced diet.

Some people with allergies or chemical sensitivities may react to higher levels, although this isn’t common. No one likes dry, flavorless preservatives, but sorbates slip in with less taste than benzoic acid or sulfites. For anyone worried about additives, remembering which foods typically contain sorbic acid helps limit intake. Homemade bread, fresh cheese from local markets, and seasonal produce offer a break from preservatives.

Practical Steps and Alternatives

Folks wanting fewer additives can stick with fresh or frozen foods, go for brands labeling their preservative use clearly, or try making snacks at home. Some organic producers use rosemary extract or vinegar for similar protection against mold. Reading labels and buying hyper-local baked goods cuts back on exposure. A few minutes searching ingredient lists helps families trust what ends up on the dinner table.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (E,2E)-hexa-2,4-dienoic acid |

| Other names |

2,4-Hexadienoic acid Preservative E200 Acid sorbic Acide sorbique Sorbinsäure |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɔːrbɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (E,2E,4)-hexa-2,4-dienoic acid |

| Other names |

2,4-Hexadienoic acid 2,4-Hexadienoic acid (E,E)- Acidum sorbicum E200 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɔːrbɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 110-44-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1906227 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30744 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1401 |

| ChemSpider | 5958 |

| DrugBank | DB09458 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.060.844 |

| EC Number | 200-768-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 26221 |

| KEGG | C02226 |

| MeSH | D013013 |

| PubChem CID | 638082 |

| RTECS number | WL2275000 |

| UNII | 1X02563L5D |

| UN number | UN 3077 |

| CAS Number | 110-44-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 771131 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30744 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1407 |

| ChemSpider | 5767 |

| DrugBank | DB02793 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.034. |

| EC Number | 200-001-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 3737 |

| KEGG | C00586 |

| MeSH | D013015 |

| PubChem CID | 6387 |

| RTECS number | WSK4376AF |

| UNII | DGH4GLY3E4 |

| UN number | UN2467 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H8O2 |

| Molar mass | 112.128 g/mol |

| Appearance | White, crystalline powder |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.204 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | 1.33 |

| Vapor pressure | < 0.1 hPa (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.76 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.73 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.556 |

| Viscosity | 2.14 mPa·s (at 175 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.69 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H8O2 |

| Molar mass | 112.13 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | Density: 1.204 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | 1.33 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.0025 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.76 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.77 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.542 |

| Viscosity | 15.5 mPa·s (75 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.72 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 218.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -711.4 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -350 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 229.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -711.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3575 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A07AX01 |

| ATC code | A07AA06 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H318: Causes serious eye damage. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: "P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | 132 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 438°C |

| Explosive limits | Explosive limits not found. |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 7,650 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 7.4 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | RN822 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Sorbic Acid: Not established. |

| REL (Recommended) | 250 mg/kg |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause an allergic skin reaction. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P233, P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P370+P378 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | 132 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 448°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 4920 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 7,500 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | RN6470 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Sorbic Acid: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | Benzoic acid |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Crotonic acid 3-Hexenoic acid Sodium sorbate Potassium sorbate Calcium sorbate |

| Related compounds |

Crotonic acid 3-Hexenoic acid Fumaric acid Maleic acid |