Sodium Sorbate: A Detailed Look at Its Role and Relevance

Historical Development

Long before people started talking about “preservatives” at dinner tables, food makers wrestled with keeping shelves stocked and products stable. The journey toward sodium sorbate kicked off as folks explored sorbic acid, first isolated from mountain ash berries over a century ago. As the food industry expanded and demands on shelf life increased, chemists began exploring different salts of sorbic acid. Sodium sorbate arrived on the scene around the mid-twentieth century. Early studies focused on extending the success of potassium and calcium sorbate, hoping sodium’s commonality and mild taste would offer new advantages. Chemists and manufacturers both contributed to gradual tweaks in formulation, always with an eye on balancing cost, solubility, and safety. These early years saw a lot of trial and error, as initial euphoria faded with growing scrutiny into food safety and preservative behavior.

Product Overview

Sodium sorbate presents itself as a preservative, mainly targeting yeasts and molds in foods. It usually appears as a white, free-flowing powder, sometimes forming granules or even small crystals. The food industry often uses it in baked goods, dairy products, drinks, and even cosmetics, seeking to tamp down spoilage without imparting odd flavors. It’s not as well-known as potassium sorbate, but in some environments where added potassium is a concern, sodium sorbate steps in as an alternative. In my experience, discussions around its use center on both its potential and its limitations—especially regarding regulatory acceptance.

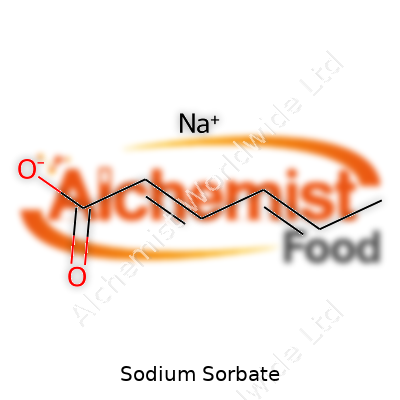

Physical & Chemical Properties

Sodium sorbate stands as a sodium salt of sorbic acid, which points straight at its key features. Its chemical formula is C6H7NaO2. Dry sodium sorbate dissolves quickly in water, laying down good groundwork for mixing into syrups, batters, or creams. Its melting point hovers around 220–232°C, and its solubility rises sharply with temperature. The colorless-to-white powder has a slight inherent taste, but nothing that usually steers product developers away from using it. Unlike potassium sorbate, it seems to have a shorter shelf life and can sometimes give off a faint odor during storage.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers grade sodium sorbate for food and industrial use, often packaging it in airtight bags or drums to shield it from humidity. Purity usually lands above 98%, with water content kept low to prevent premature clumping or degradation. On labels, you’ll run across its E number—E201—though not everywhere. Countries like the United States and several EU member states don’t approve sodium sorbate for food use, given toxicity debates. Where it’s accepted, labels need clear identification, batch codes, and country of origin. Product sheets include analysis certificates, outlining heavy metal content, pH range (around 7–9 when dissolved), and typical usage rates by product category.

Preparation Method

Process-wise, sodium sorbate often starts with sorbic acid, itself derived from crotonaldehyde and ketene in large chemical plants. Producers neutralize sorbic acid with sodium hydroxide, producing the salt and water. After careful filtration to remove impurities, the resulting solution evaporates to yield the solid salt. Technicians must monitor temperature and pH all the way through, since high temperatures or chemical imbalance can reduce yield or cause unwanted byproducts. In most modern factories, the process unfolds in sealed vessels, reducing contamination and exposure for workers.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

One thing that comes up with sodium sorbate is its instability, particularly in moist or acidic environments. It can react with acids to re-form sorbic acid, sometimes shifting organoleptic properties of foods. Under highly oxidative conditions, it deteriorates into aldehydes, producing off-flavors. As with other sorbates, energy from ultraviolet light can trigger breakdown, so packages need light-blocking features. In the lab, minor chemical modifications have aimed to strengthen resistance to breakdown, but cost and efficacy keep these efforts at the experimental stage. Sodium sorbate does not react well with iron or copper, so direct contact with certain food-processing equipment can spur spoilage or color changes—a headache for process engineers.

Synonyms & Product Names

Shoppers or researchers sometimes find sodium sorbate under other labels: E201, sodium (2,4-hexadienoate), and the less-used “hexadienoic acid sodium salt.” Commercial suppliers throw around house brand names, but the core identity doesn’t change. Its family includes potassium sorbate (E202) and calcium sorbate (E203), all targeting similar spoilage problems with some tweaks in solubility and flavor impact.

Safety & Operational Standards

Food safety bodies like the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) draw clear lines regarding sodium sorbate’s use. Regulatory rejections stem from early studies showing higher toxicity than related sorbates, especially when residual impurities pop up. Some tests suggest mutagenicity at high concentrations, though these doses fall far above what a typical person would encounter in processed food. Factory staff must use personal protective equipment to avoid skin and lung contact, since the powder can irritate mucous membranes. HACCP planning includes careful inventory control—absent-minded mixing with high-acid foods can backfire, ruining batches.

Application Area

Most applications for sodium sorbate have cropped up in baking, cheese making, and soft drink production, at least where it’s permitted. Cosmetic makers once eyed its antifungal potential, but safety concerns steered many toward other preservatives. Soap and detergent manufacturers tried using it, betting on its ability to stand up against yeasts. Wherever people use sodium sorbate, they keep an eye on regulatory news and customer preferences, since approval status can shift as new studies come out.

Research & Development

Researchers keep tracking how sodium sorbate works in different foods and under different storage conditions. They compare its effectiveness against potassium and calcium sorbates, hunting for new blends or processing tweaks that could reduce spoilage without safety trade-offs. I’ve seen research teams run accelerated aging studies in bread and soft cheeses, observing how sodium sorbate inhibits surface molds. Some lab groups keep experimenting with encapsulation, aiming to shield the compound from early breakdown and avoid flavor changes. So far, the more successful R&D stories seem to emerge from places where sodium sorbate enjoys clear regulatory footing, fueling more investment and deeper investigations.

Toxicity Research

Safety studies drove decision makers to limit or block sodium sorbate’s use in some major markets. Animal experiments flagged kidney and liver issues at extremely high doses, spurring scientists to dig deeper. Some research pinpoints breakdown products—such as trans,trans-muconaldehyde—as potential sources of concern. Critics contest that food-grade sodium sorbate, used at recommended rates, rarely approaches toxic levels in diets. Still, uncertainty persists, especially with mounting research on long-term, low-level exposure. Regulatory bodies continue to digest findings, and many choose to err on the side of caution. Food producers weigh these safety signals against proven benefits, often opting for the less-controversial potassium or calcium variants.

Future Prospects

Looking forward, sodium sorbate faces an uphill climb in many markets. As food and cosmetic manufacturers chase cleaner labels and lower perceived risks, they often bypass sodium sorbate in favor of better-tested options. Still, researchers and some niche players hope that better manufacturing controls, purity upgrades, and informed risk assessments might swing the tide a bit. Ongoing investment in analytical chemistry could isolate safer manufacturing methods and minimize trace contaminants, possibly restoring trust. In regions with looser restrictions, sodium sorbate might hold its ground longer as a dependable, cost-effective tool. To change its reputation more widely, the industry would need coordinated research into chronic exposure and breakdown products, plus frank communication with both regulators and consumers.

What is Sodium Sorbate used for?

Digging Into This Food Ingredient

Step through any supermarket and you’ll spot preservatives on the ingredient lists of so many products. Sodium sorbate is one of those names that comes up. It grabs the interest of anyone focused on clean eating or food safety because it’s tied to a bigger conversation: what do we add to our food, and why?

Why Producers Use Sodium Sorbate

Food spoils. That’s the reality. Bacteria, mold, and yeast start growing as soon as the right moisture and warmth show up. Sodium sorbate fights this. It keeps things like cakes, cheeses, and pickles from going bad before they even reach your kitchen. This preservative stretches shelf life, protects taste and texture, and cuts down on waste. If people stopped using sodium sorbate, a lot more food would end up in the trash, especially products that travel long distances from factory to store.

Safety and Trust: What the Science Says

Some folks worry about the chemicals in their snacks and staples, so food scientists and health officials keep a close watch on sodium sorbate. Research shows it stops spoilage microbes without sticking around in the body. It gets broken down and flushed out quickly. In small amounts, studies say it doesn’t trigger health problems for most people.Regulators in places like the US and European Union put clear limits in place for how much food can contain. The real issue crops up when manufacturers cross the safe line and use more than allowed. Strict labels and audits help keep those risks in check.

Should We Worry About Preservatives Like This?

Trust in food depends on open information and honest science. Headlines about synthetic additives might make sodium sorbate sound worrisome, but facts help sort fear from fact. Rates of allergic reactions remain extremely low. It doesn't build up over time, and eating a steady diet of preserved food hasn’t shown any link to big health scares tied to this compound. People with sensitive systems or food allergies do need to pay attention, though. Anyone can learn more by looking up reliable sources like the FDA, European Food Safety Authority, or medical research libraries.

Better Solutions and Moving Forward

Scientists and manufacturers keep searching for ways to make food safer while feeding more people. Some are working on natural preservatives from herbs or fermentation byproducts. Others push for cleaner labels, with clear explanations and fewer ingredients. Shopping more often, storing food smartly, and supporting local producers can also help limit the need for preservatives. If shoppers demand transparency and safe limits, companies are more likely to deliver food people feel good eating.

Years of research shaped what goes into food today. The real path forward puts evidence first, listens to consumer voices, and steers clear of scare tactics. Sodium sorbate makes our meals last longer and safer, and thanks to science, we know a lot about how to use it without crossing the line.

Is Sodium Sorbate safe for consumption?

Digging Into Food Preservatives

Nowadays, almost every processed food comes loaded with something to keep it fresh longer. Food safety and shelf life take priority for manufacturers. Among these additives, sodium sorbate grabs attention, but plenty of folks wonder if it belongs in their diets.

What Is Sodium Sorbate?

Sodium sorbate preserves food by fighting off mold, yeast, and fungi. As a salt derived from sorbic acid, it keeps baked goods, cheeses, spreads, dried fruits, and other products stable for much longer. Unlike some preservatives, you’ll find sorbates have earned their spot because they do their job without a strong aftertaste or odor.

Research and Safety Record

Scientists don’t take food additives lightly. Most attention goes to potassium sorbate and calcium sorbate, both well-studied and cleared by regulators in the U.S. and Europe. Sodium sorbate carries less research baggage, which keeps food safety watchdogs alert. In 2002, the European Food Safety Authority raised questions about the way sodium sorbate reacts in the body compared with its cousins. Lab work showed possible genotoxic effects (damage to cellular DNA) under specific test conditions. This prompted a halt on its approval for use in European food products.

In the U.S., sodium sorbate doesn’t enjoy the same “Generally Recognized As Safe” status as potassium or calcium sorbate. The Food and Drug Administration hasn’t given the green light, so you won’t run into sodium sorbate in most packaged products on American grocery shelves.

Why Does This Matter?

In practice, regulatory caution exists for a reason. We trust agencies because food safety shapes public health. Additive bans or approvals aren’t just paperwork; they come from lab data and human review. As someone with a sensitive gut, I pay close attention to preservatives. I have seen how poorly-tolerated additives can make symptoms worse, not better. I look out for clear ingredient lists and stick with options I recognize.

A lot of friends and family take the same path, checking labels before tossing things in their carts. Even if one product claims “no added preservatives,” a cousin version might quietly include a newer additive not seen much before. In the age of allergies and food sensitivities, transparency isn’t just a trend—it’s what people deserve.

Natural vs Manufactured Solutions

Food companies turn to sorbates because they work well at low doses, meaning the product keeps better without a pantry full of chemical ingredients. Bread lasts longer, shredded cheese resists mold, and fruit snacks don’t turn fuzzy after a few days. Still, not every preservative gets the same treatment. Potassium sorbate, for example, ranks as a go-to for shelf life. Sodium sorbate, by contrast, hasn’t passed the same safety checks.

Safer Alternatives and What Shoppers Can Do

Look for clear labeling and stick to reputable sources. Potassium sorbate and calcium sorbate pass routine checks and enjoy a long track record. For those with concerns, naturally preserved foods or homemade alternatives might prove safer bets, especially for kids or those with chronic conditions. Checking in with a registered dietitian or seeking advice from your healthcare provider sets a solid foundation for people with extra concerns about food chemicals.

Researchers and companies need to keep digging. Every time a new food preservative emerges, it deserves a clear, honest look. Open access to findings and government records helps people make the call for themselves, instead of feeling lost in a sea of technical jargon.

What are the side effects of Sodium Sorbate?

The Food Preservative on Our Shelves

Sodium sorbate keeps mold off baked goods, cheeses, dried fruit, and helps many foods stay fresh longer. Walk down any aisle and you’ll find it on ingredient labels. Most folks never think about it. This additive works by stopping yeast, mold, and some bacteria from growing. This quality earned it a place in the food industry, but questions about side effects deserve more attention than they tend to get.

Spotting the Risks Amid the Benefits

Plenty of preservatives have their issues. With sodium sorbate, science hasn’t uncovered a safety record as long or solid as its close cousin, potassium sorbate. Potassium sorbate carries GRAS status from the FDA. Sodium sorbate fell out of favor in many countries—Europe being one example—over evidence it can irritate the skin, eyes, and respiratory tract more than other preservatives. The European Food Safety Authority took a hard look and found that this additive can sometimes spark allergic reactions, especially at higher concentrations.

Some people touch or eat foods with sodium sorbate and break out in hives or eczema. Itchy skin, redness, and swelling can happen. Eyes might water or sting, and contact can make respiratory symptoms worse. Those with asthma may notice more trouble after a meal with this preservative. Allergies and intolerances show up differently for everyone, but the connection feels real to anyone who has lived through a nasty rash or food-triggered cough.

What Science Has to Say

Rodent and cellular studies form the backbone of much of the research on sodium sorbate. Some findings suggest this additive may harm cell DNA at high concentrations. Evidence in people is still lacking, so experts debate if low levels found in foods add up to long-term risk. The European Union decided not to allow sodium sorbate as a food additive after data pointed to possible toxicity. Other countries restrict use or set low legal limits. Scientists call for more testing, since food safety needs clear data and new allergies pop up as diets change.

Deciding What Goes on Your Plate

Many dietitians, myself included, recommend reading food labels and keeping a varied, fresh diet. Fresh or frozen foods without synthetic preservatives cut down the chances of coming into contact with irritants. People with allergies, eczema, or asthma already spend time dodging problem foods. Adding sodium sorbate to the watch list may help, especially for those who notice symptoms after packaged meals or baked treats. If you suspect a reaction, track what you eat and talk with your doctor or a registered dietitian.

Pushing for Transparent Food Choices

Side effects go beyond statistics and lab tests. They matter because real people live with skin rashes, breathing trouble, and food fears. Food manufacturers have the tools to make preservative-free foods, and shoppers have the power to choose products with shorter, recognizable ingredients lists. With rising food allergies and sensitivities, clear labeling becomes more important. Let’s push for honest food labels and more research, so everyone can decide what they want—and do not want—at the table.

Sources: European Food Safety Authority, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Journal of Food ProtectionHow is Sodium Sorbate different from Potassium Sorbate?

Understanding Food Preservatives in Everyday Life

Most folks shopping for groceries will spot potassium sorbate on nutrition labels. It’s common in cheese, baked goods, and drinks because it stops mold and yeast. Sodium sorbate sounds like its twin, but it doesn’t have the same story in the food world. Even though they share the sorbate family name, their roles and safety are different, something I learned digging through ingredient checklists trying to keep my family's food choices safe.

Potassium Sorbate’s Proven Track Record

Potassium sorbate gets the green light from safety authorities, including the FDA and EFSA. Brands reach for it because it's reliable and harmless in the amounts used, according to decades of research. This preservative dissolves easily in water, making it ideal for clear drinks and soft foods. I’ve seen potassium sorbate stretch the life of homemade jams and soft tortillas, saving money and cutting down on food waste. The science matches that experience—studies show it prevents spoilage without changing the taste or texture when used right.

Sodium Sorbate: Trouble with Safety Standards

Sodium sorbate might look like an alternative, but regulatory bodies worldwide reject it for human food. Testing raised concerns about toxic effects that don’t come with potassium sorbate. The European Food Safety Authority pulled the plug on sodium sorbate, citing risks with repeated exposure. Real world experience backs this up; I couldn’t find a single large food brand willing to stand behind sodium sorbate use, and that points to trust issues and safety gaps. Even small food producers who value natural preservatives stay far from sodium sorbate after reading the fine print.

Potassium Content and Sodium Concerns

One reason food scientists lean into potassium sorbate involves public health. High sodium diets link to high blood pressure and heart issues. Consumers look for sodium-free solutions everywhere. Potassium sorbate fits this demand, since it doesn’t add any sodium. Potassium actually helps balance blood pressure, and most people get too little of it. That added bonus lines up with what nutritionists—and my own doctor—keep recommending: get less sodium, aim for more potassium. Sodium sorbate heads in the wrong direction, further raising sodium levels in packaged foods.

Longevity, Taste, and Innovation

Potassium sorbate preserves freshness without leaving any aftertaste or chalky feel in foods. You won’t notice it in a glass of cider or a strawberry pie, unlike sodium-based additives that sometimes tip off the tongue. Wider use comes down to performance and reputation. Chefs, bakers, and home cooks trust potassium sorbate to keep products appealing from kitchen to table. Manufacturers invest in new blends and delivery forms that make potassium sorbate even easier to use safely. I’ve followed its track in the market for years, and it remains the clear workhorse in food preservation.

Solutions for a Safe Food Supply

The science says the risks with sodium sorbate outweigh any slight benefit from its cost or chemical profile. Potassium sorbate stands up to scrutiny and blends into everyday eating. People can boost their food’s shelf life and help avoid food waste by choosing products listing potassium sorbate, skipping those with low-tested or unapproved alternatives. Regulators, scientists, and shoppers share the job of making sure what shows up on shelves is safe, trustworthy, and truly serves our health.

Is Sodium Sorbate approved by food safety authorities?

A Look at Food Additive Approval

The world of food additives gets complicated really fast. At the store, most shoppers spot those long, odd names at the end of an ingredient list and trust that someone, somewhere, checked if they’re safe. Authorities like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) guard that gate. Their approval gives everyone down the food chain—manufacturers, bakers, families—a signal that the additive passed basic safety tests.

Sodium Sorbate—A Different Story

Most people have heard of sorbates because of potassium sorbate or even calcium sorbate—trusted preservatives that help bread, cheese, and fruit juice last longer. But sodium sorbate tends to provoke a puzzled look. Despite sounding similar, sodium sorbate never got the official green light from major regulators. Both the FDA in the United States and EFSA in Europe withhold approval for sodium sorbate as a food additive.

EFSA actually went so far as to issue an explicit opinion in 2015, stating that sodium sorbate led to toxicological concerns—they spotted health risks in the scientific data and saw no good case to approve its use. Similar rulings echoed in regulatory documents around the world. Food manufacturers take those decisions seriously. One of the fastest ways to lose consumer trust or face expensive recalls starts with ignoring the food safety rules.

Ingredient Integrity: Why Scrutiny Counts

Many food scientists, myself included, learned the value of double-checking every single substance planned for a recipe. Ingredients can look similar in structure but react differently in our bodies. Sodium sorbate just didn’t pass rigorous safety reviews. For customers, this means you won’t see sodium sorbate on lists of approved additives and shouldn’t find it in reputable products.

Government authorities and scientists focus hard on the details: animal studies, how substances break down in the stomach, what happens over long exposure. It’s a tough job—balancing innovation in the food world with strict consumer protection. While potassium sorbate scored approval for its safety record and effectiveness, sodium sorbate couldn’t clear that bar.

The Human Side of Food Safety Decisions

A lot of us have memories of scanning ingredient lists, either by habit or out of caution for allergies or dietary reasons. Food safety standards have improved dramatically since the days when manufacturers slipped almost anything into packaged foods. Food authorities don’t just respond to scientific data but also public concern—no one wants to see a repeat of old, preventable food safety disasters.

Regulatory approval plays a practical role. It sets a baseline level of protection for everyone; without it, risky substances make their way into lunchboxes and family dinners. Even though a chemical cousin may be safe, nobody can assume every related additive is harmless. The sodium sorbate example reminds us that not every innovation reaches market shelves, and not all that sounds familiar earns a spot in our food supply.

Better Solutions Depend on Trust

Trusting food means trusting the regulatory process. Authorities lean on peer-reviewed science—collecting proof, not guesswork. Public access to these decisions keeps companies honest, families protected, and the whole food supply more secure.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | sodium (2E,4E)-hexa-2,4-dienoate |

| Other names |

Sorbic acid, sodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm ˈsɔːr.beɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | sodium (2E,4E)-hexa-2,4-dienoate |

| Other names |

Sorbic acid sodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm ˈsɔːrbeɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7757-81-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3592473 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:32225 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1350 |

| ChemSpider | 70753 |

| DrugBank | DB11151 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.030.252 |

| EC Number | E 201 |

| Gmelin Reference | 28459 |

| KEGG | C18525 |

| MeSH | D017370 |

| PubChem CID | 23680582 |

| RTECS number | WI6806000 |

| UNII | 9043-98-9 |

| UN number | UN 1759 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8036397 |

| CAS Number | 7757-81-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `[Na+].C=CC(=O)[O-]` |

| Beilstein Reference | 1901273 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:32233 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL135653 |

| ChemSpider | 133080 |

| DrugBank | DB11149 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.274 |

| EC Number | 231-295-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 82252 |

| KEGG | C18567 |

| MeSH | D015547 |

| PubChem CID | 23684095 |

| RTECS number | WV9175000 |

| UNII | O6XEA9392T |

| UN number | UN2813 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | NaC6H7O2 |

| Molar mass | 150.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 1.27 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -2.7 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.76 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 9.13 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.441 |

| Viscosity | Viscosity (20°C): 5 mPa·s (5 cP) |

| Dipole moment | 1.82 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H7NaO2 |

| Molar mass | 150.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.41 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -7.17 |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa 4.76 (for sorbic acid) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.77 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -53.0e-6 cgs |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.451 |

| Dipole moment | 2.48 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 253.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 234.9 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A01AD20 |

| ATC code | A01AD11 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: "P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-1 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Rat oral > 10,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 7.5 g/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | WFN22000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL not established |

| REL (Recommended) | '20 mg/kg' |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P312, P337+P313, P362+P364 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 1, Flammability: 1, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Autoignition temperature | 400 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 7,200 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 4,950 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | UNII:24J99466ZK |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL not established |

| REL (Recommended) | Not recommended (see notes) |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sorbic acid Potassium sorbate Calcium sorbate |

| Related compounds |

Sorbic acid Potassium sorbate Calcium sorbate |