Sodium Saccharin: A Closer Look at a Controversial Sweetener

Historical Development

Back in the late 1800s, Constantin Fahlberg was working in a Johns Hopkins University lab. He accidentally discovered saccharin after a long day synthesizing various chemicals from coal tar. He noticed a sweet taste on his hands, traced it back to his experiments, and soon recognized this remarkable sugar substitute. The world was hungry for low-calorie sweetness, especially during sugar shortages in the World Wars. People quickly embraced synthetic options like sodium saccharin, long before sucralose or aspartame came on the scene. Over decades, sodium saccharin earned its place in kitchens, chemistry sets, and regulatory debates because, for millions, it seemed to offer the answer to dietary and economic concerns tied to natural sugar.

Product Overview

Known for its intense sweetness—hundreds of times greater than table sugar—sodium saccharin pops up in everything from diet sodas to toothpaste. The food industry leans on it to provide sweetness without calories, since metabolic processes do not break it down as energy. This characteristic appeals to the growing number of people watching calorie intake or struggling with diabetes. Granular or powdered, sodium saccharin dissolves rapidly, making it easy to blend seamlessly in both industrial manufacturing and home kitchens.

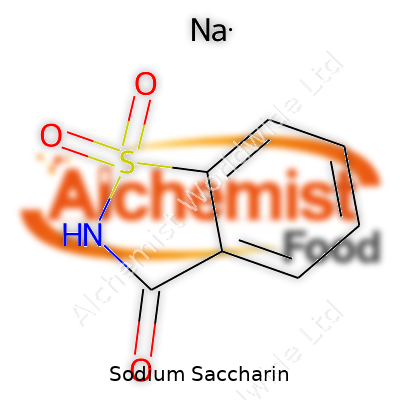

Physical & Chemical Properties

Chemists describe sodium saccharin as a white, crystalline powder, with a melting point of around 225°C before it starts to decompose, and an unmistakable sweet flavor that can almost feel metallic or bitter to sensitive palates at higher concentrations. Its water solubility means beverage manufacturers don’t need to jump through hoops to integrate it into recipes. The compound’s stability across a wide pH range and resistance to both heat and light explain why companies have trusted it for decades in shelf-stable products. The chemical formula, C7H4NNaO3S, plus a molecular weight of about 205 grams per mole, defines its technical backbone.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

For the food and beverage world, sodium saccharin generally comes with purity north of 99%. Regulations cap the allowable levels and dictate strict limits for contaminants like arsenic and heavy metals, matching food safety expectations. The legal framework sets requirements for product labeling, with packs carrying clear markers, including the "artificial sweetener" tag and disclosure of concentration. Brands and ingredient suppliers stay vigilant, knowing consumers and watchdogs both check those details before products reach supermarket shelves.

Preparation Method

Industry synthesizes sodium saccharin through several routes. The most common starts with anthranilic acid, which reacts with nitrous acid, sulfur dioxide, chlorine, and then ammonia. Each step in this process produces intermediates, but the endgame is always that sweet, water-soluble powder. Manufacturers employ strict controls and purification steps to ensure the sodium saccharin meets not just sweetness but safety standards. Cleanroom gear and rigorous monitoring help achieve this, protecting workers and keeping finished batches free from impurities.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Once in hand, sodium saccharin resists many forms of degradation, giving it impressive shelf life. Chemists have worked on tweaking its structure to address flavor profile quirks or compatibility issues in industrial blends. Mixing with other sweeteners, such as aspartame or cyclamate, usually softens some of sodium saccharin’s aftertaste and balances sweetness perception. Researchers also look at derivatives for specialty uses, but the original sodium salt remains the workhorse of the additive world.

Synonyms & Product Names

Supermarkets and ingredient lists rarely call it by its formal chemical name. You’ll spot sodium saccharin listed as E954, saccharin sodium, or simply saccharin in ingredient panels. Some trade names feature Sweet‘N Low or SugarTwin, anchoring the substance in the collective consumer memory. This web of names often causes confusion, so consumers rely heavily on regulatory labeling to unravel what’s actually in their food or medications.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety sparked heated debates for decades. In the 1970s, lab studies in rats raised concerns about bladder cancer risk, resulting in warning labels for products in the United States. Later scientific scrutiny revealed these effects occur under laboratory conditions unlikely to be matched by human consumption. Today, most leading agencies, including the FDA and European Food Safety Authority, consider sodium saccharin safe when people stay within recommended daily limits. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives set the acceptable daily intake at 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, and most real-world diets land far below this. Nonetheless, food and pharma firms maintain robust operational standards, with plant hygiene, cross-contamination controls, and rigorous quality checks underpinning every batch. Workers have to take serious measures to keep dust exposures low, both for respiratory safety and to meet standards for pharmaceutical or food-grade ingredients.

Application Area

Sodium saccharin’s reach extends well beyond soda and tabletop sweeteners. Food processors use it in baked goods, jams, jellies, chewing gum, desserts, and canned fruits to keep sugar levels down and flavor high. Toothpaste and oral hygiene products tap saccharin for sweetness without promoting tooth decay. Medications, especially syrups and chewable tablets, mask medicinal bitterness using saccharin-based formulations. Animal feed and even electroplating solutions count on sodium saccharin for specialty technical reasons, such as serving as a brightener in metalworking. Its compatibility with other stabilizers explains its continued use even as rival sweeteners join the market. Food scientists leverage this additive for its consistency and long track record.

Research & Development

Laboratories and manufacturers invest time and resources to make sodium saccharin not only sweeter but also better accepted by consumers sensitive to its flavor quirks. One research avenue explores encapsulation, reducing bitter aftertaste in finished products. Another trend includes looking for new production routes with greener chemistry, such as bio-based raw materials or processes that use fewer hazardous reagents. Others want to combine sodium saccharin with plant-derived sweeteners, searching for new flavors and profiles in response to consumer demand for “natural” products. Projects also examine its interaction with other ingredients, searching for ways to improve product texture and shelf stability without complicating regulatory hurdles.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists dove deep into sodium saccharin’s effects over the past half-century. The famous rodent studies from the 1970s triggered regulatory changes, consumer concerns, and ambitious research programs. More refined long-term studies and improved epidemiology in humans quickly separated rat-specific risks from human realities, so health agencies eventually dropped cancer warnings. Chronic exposure at levels seen in standard diets has not triggered lasting health effects in humans. Researchers continue looking at whether saccharin influences gut microbiota, metabolism, or other subtle physiological systems. Cumulative knowledge keeps scientists alert, knowing food technologies need to adapt if new threats emerge.

Future Prospects

Artificial sweeteners keep gaining ground as more countries grapple with obesity, diabetes, and ever-tightening sugar taxes. Plant-derived sweeteners—like stevia—grab headlines, but sodium saccharin’s stability and cost mean it probably won’t disappear soon. Future markets may reward innovation around taste, allergen avoidance, and eco-friendly production. As analytical techniques advance, researchers keep tight tabs on long-term impacts, fully aware society expects transparency, accountability, and evolving safety standards. The future will likely feature sodium saccharin not as a lone hero, but as a member of an expanding roster of sweetening tools. No matter where technology leads, the industry must answer to science and shifting consumer values, balancing tradition with progress as health trends and food cultures evolve.

What is Sodium Saccharin and how is it used?

Understanding Sodium Saccharin

Sodium saccharin often pops up in ingredient lists for drinks, baked goods, and even toothpaste. A synthetic sweetener older than most people's grandmothers, it delivers intense sweetness without the calories. I remember seeing those pink packets at diners and realizing that this sweetener comes from a chemical process, not a plant or fruit. One tiny pinch can be hundreds of times sweeter than regular table sugar, so manufacturers use only a fraction to flavor products.

The Many Faces of Sweetness in Everyday Life

People who manage diabetes or watch their calorie intake sometimes reach for foods and drinks made with sodium saccharin. The compound helps cut sugar while keeping that sweet flavor alive. Fast food chains, soda companies, and chewing gum brands rely on sodium saccharin to create sugar-free versions that catch the eye of health-minded shoppers. For someone who is careful about blood sugar levels, those diet sodas or light yogurts offer a treat without the side effects of regular sugar.

Manufacturers also turn to sodium saccharin because it resists heat. Baking at high temperatures can ruin weaker sweeteners. Sodium saccharin holds up, so baked goods stay sweet without losing their taste after a trip through the oven. I’ve talked with bakery owners who like having an option that keeps their sugar-free pastries tasty enough for kids and adults who can’t or won’t eat regular sugar.

Food Safety and Sodium Saccharin

Safety concern always crops up with artificial ingredients. Historical studies raised questions about saccharin’s risk in lab rats, fueling fears over long-term health impact. Later research couldn’t link current human use to the same risks, so health agencies revised their stance. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, European Food Safety Authority, and World Health Organization set daily intake levels that remain well above what most people ever eat or drink.

People often ask me if sodium saccharin is “safe” or “natural.” While no one finds it in a fruit or vegetable, it goes through careful safety checks because of how commonly it shows up on shelves. Many manufacturers publish testing results to assure consumers and buyers, so the question of quality doesn’t go unanswered. If a product comes from a reputable brand and follows regulations, sodium saccharin appears in safe amounts.

Solutions for Better Choices

Some shoppers look at ingredient labels, spot sodium saccharin, and put the product back in search of a different sweetener. Others pick it up without hesitation. Facing so many choices, it’s tough to know what’s best. Educating families and schools about different sweeteners, explaining how they work, and sharing facts helps everyone make choices that fit their needs and health goals.

For me, moderation stands out as the guiding principle. Adding a coffee sweetener now and then doesn’t mean abandoning a healthy lifestyle. Staying informed and paying attention to how different foods affect energy and mood leads to greater confidence in picking what goes onto our plates. Products with sodium saccharin offer a tool, not a mandate, for people striving to balance sweetness and health.

Is Sodium Saccharin safe for consumption?

Understanding Sodium Saccharin

Sodium saccharin landed on my kitchen table in the 1990s, tucked into the little pink packets at diners and my grandparents’ coffee shop. Touted as a calorie-free substitute for sugar, it delivered the promise of sweetness without the fallout of an expanding waistline. As a kid, I never thought about what sweetened my lemonade except that it did the trick.

Fast forward, and sodium saccharin appears on ingredient labels everywhere—from diet sodas to toothpaste. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use long ago, after decades of back-and-forth over whispers of health concerns. After all the to and fro, saccharin carries a green light for consumption, but many folks still wonder if it’s actually safe.

Looking Into the Safety Concerns

Back in the 1970s, one study on rats suggested saccharin might cause bladder cancer. This headline stirred fear: major health organizations pressed pause, and even Congress stuck warnings on saccharin packets. The average person—my parents included—chose to switch to "natural" sweeteners or went back to sugar. The tide eventually turned when researchers dug deeper. The type of cancer found in rats didn’t pop up in people. Science points to the difference in rat urine chemistry compared with humans. Repeated reviews showed no strong link between saccharin and cancer in humans. In 2000, the National Toxicology Program pulled saccharin from its list of potential cancer-causing chemicals.

Every agency from the FDA to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) now gives saccharin a stamp of approval. Each group reviews stacks of studies that check for links to cancer, allergies, and otherwise. Sure, some people still report a bitter aftertaste or mild allergic reactions, usually if they deal with sulfa allergies. For the vast majority, saccharin sweetens without incident. Its use in toothpaste, candies, and low-calorie snacks stretches globally.

Why This Matters – My Take

Our modern food environment dangles ultra-sweet flavors all day, every day. So the puzzle: how can we enjoy our favorite treats with less added sugar—without creating other health risks? Saccharin offers one route. In my own efforts to cut down on sugar, non-nutritive sweeteners made a big difference for my blood sugar. Research backs up the safety of saccharin and shows it doesn’t raise blood glucose the way table sugar does, which matters for people living with diabetes or those aiming to drop a few pounds.

Excess sugar taxes our health, raising risk for obesity, heart disease, and even some cancers. Agencies like the American Heart Association urge limits, well below what most folks consume today. So alternatives like saccharin aren’t just trendy—they help millions manage their health.

Pay Attention to How Much You Use

No single ingredient solves everything. Saccharin on its own won’t undo a diet packed with processed foods. It works best as one tool, not the foundation. Taste buds easily adjust over time to less sweetness—swapping sodas for water does more than switching to diet pop, in my experience. The FDA set an acceptable daily intake (ADI) far above what people hit in normal use, so the risk from moderate consumption stays low.

For anyone curious or concerned, looking at the bigger eating patterns helps more than focusing only on one additive. Choosing foods closest to their original state and using processed sweeteners sparingly always points in the right direction for long-term health.

What are the main applications of Sodium Saccharin?

In the Food and Beverage Industry

Growing up, I watched my grandmother avoid sugar for her health. Her cupboard always had those little pink packets—sodium saccharin. This sweetener has been stepping in for sugar for over a century. It shows up in diet sodas, sugar-free gums, and tabletop sweeteners. Lab tests reveal that saccharin brings about 300 to 500 times more sweetness than regular table sugar. Food producers like it because it holds up during baking and stays stable in cans or bottles—heat and acid don’t break it down. It keeps sweets, jams, and drinks palatable for people watching their calorie and sugar intake.

Pharmaceutical Uses

Saccharin finds a home in medicines. Many liquid meds—think cough syrups or chewable tablets—would taste pretty bad without something to mask the bitterness. Pharmacists learned to add a pinch of saccharin to make medicine easier for kids and picky adults to stomach. Studies published in drug formulation journals confirm that low-calorie sweeteners don’t interact with many of the active drug ingredients. This quality helps ensure patients stick with their medicine as prescribed.

Personal Care and Oral Hygiene

Brushing your teeth feels a little more tolerable thanks to saccharin hiding in toothpaste and mouth rinses. Most people don’t think about why toothpaste tastes pleasant, but a look at labels shows sodium saccharin on many ingredient lists. The sweetness helps mask the taste of stuff like fluoride and abrasives. Since saccharin doesn’t feed bacteria like regular sugar, it helps dental products stay cavity-friendly. Cosmetic giants also add it to lipstick, mouth sprays, and dental floss. The amounts stay small, well below levels that health agencies warn about.

Industrial and Technical Roles

Moving away from the kitchen and medicine cabinet, saccharin even has some surprising jobs. Plating factories—a place I once visited with a school group—use saccharin in electroplating baths. Nickel plating often needs this compound to polish and smoothen metal surfaces. Tech experts point out that just a small dose in the solution results in a shinier, more durable coating. Some companies use it in herbicides and pesticides, where a sweet taste helps with coating seeds or attracting pests. Research articles from chemistry circles back up these technical uses, showing saccharin’s adaptability.

Safety and Public Perception

Many people remember scary headlines about saccharin in the late 1970s, linking it to cancer in early rodent studies. Since then, scientists from groups like the World Health Organization and the FDA have taken another look and cleared up many worries. Decades of new evidence and human trials—summarized in reports from the National Institutes of Health—show no clear link between saccharin and cancer in people, provided intake stays within guidelines. Manufacturers label their products so consumers know exactly what they’re eating or drinking.

Looking Forward

As populations around the world continue searching for lower-calorie choices, and as diabetes climbs in many countries, sodium saccharin remains important. There’s ongoing work in both food science labs and health policy offices to make sure that artificial sweeteners like saccharin deliver safety, taste, and value. It’s amazing to think one compound can pop up in so many places, from a soda bottle to a shiny car bumper.

Are there any side effects of Sodium Saccharin?

The Lowdown on Sodium Saccharin

Sodium saccharin pops up everywhere: diet sodas, packets of tabletop sweetener, processed snacks, and even toothpaste. It’s sweet, sometimes bitter, and way sweeter than sugar—about 300 times stronger. For decades, it’s been the go-to option for people trying to cut sugar. People lean on saccharin for weight management, diabetes, and keeping calories down, but the big question lingers: What's the trade-off for a sugar taste without the sugar?

Recognizing Common Side Effects

Some folks notice a metallic or bitter note with saccharin. I’ve felt it myself when I’ve poured a packet into my coffee, looking for sweetness but grimacing at a strange aftertaste. Taste is personal, but for those trying to quit real sugar, switching to saccharin can feel disappointing because of that lingering note.

There are more than taste complaints. Some people deal with allergic reactions, especially asthma sufferers or those allergic to sulfa drugs. Symptoms range from hives to wheezing and trouble breathing. That’s not most users, but these reactions are well documented in medical sources like the National Institutes of Health. If someone with these sensitivities tries saccharin, they could end up with more than just an odd taste in the mouth.

Digestive Woes and Big Debates

Some report digestive issues after consuming too much sodium saccharin. Bloating and mild stomach upset are among the complaints. Saccharin passes through the body mostly unchanged, so it can ferment in the gut and mix things up for people with sensitive stomachs. Anecdotally, a friend of mine—attempting to swap out sugar entirely—ran into unexpected stomach discomfort from adding saccharin to everything. Small amounts worked fine, but piling it on did not.

The big scare decades ago was cancer risk. In the 1970s, lab rats developed bladder cancer after eating huge amounts of saccharin, leading to warning labels on products in the US for years. Later research, including large-scale human studies, found that saccharin doesn't trigger the same cancer risk in people. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and WHO reviewed these results and cleared saccharin for normal use. Still, old fears linger with people who remember that era.

What Does Science Say?

Medical research holds the most weight for something so widely used. Reviews show saccharin doesn’t spike blood sugar, so it’s safer for diabetics than regular sugar. Scientific bodies have set limits far above what most people ever reach; you’d need to eat hundreds of packets a day to hit risky territory. The FDA, WHO, and the European Food Safety Authority agree: realistic consumption hasn't shown clear evidence of harm for most people.

Practical Ways to Use Saccharin Safely

Trusting nutrition information means looking at more than headlines. For one thing, rotating between different sweeteners keeps intake in check. People sensitive to saccharin’s aftertaste or who notice allergies should talk to a doctor or nutritionist before switching sweeteners entirely.

Relying on a wide assortment of nutritional sources—fruits, whole grains, regular sugar in reasonable amounts—lessens the urge to stack up on any one artificial sweetener. For me, mixing up my flavors and not expecting any sweetener to deliver a perfect substitute brought more satisfaction and less worry.

Saccharin can help cut calories and support blood sugar management. Like any food ingredient, moderation pays off, and listening to your own body's response matters more than old scare stories or the marketing on a pink packet.

How does Sodium Saccharin compare to other artificial sweeteners?

Personal Experience at the Supermarket

I remember checking out the sweetener aisle at my local supermarket. Rows and rows of little packets, each promising the same thing — sweetness without sugar. It struck me how one small blue packet labeled “sodium saccharin” and another yellow one marked “sucralose” claimed to do the same job, yet each played a very different role in my morning coffee. Sodium saccharin has a legacy stretching back to the late 1800s, and many people still reach for it when they want a calorie-free sweetener. Still, anybody who’s tried different sweeteners can tell there’s more to the story than just “sweet or not.”

Taste and Everyday Use

Sodium saccharin packs an intense punch — it's about 300 times sweeter than table sugar. Some coffee drinkers pick up a slightly bitter, metallic aftertaste, which isn’t as common with other sweeteners like aspartame or sucralose. If someone grew up with saccharin in their iced tea, that taste might actually feel nostalgic. These days, brands usually blend it with other sweeteners to mask any bitterness.

Saccharin survives heat, making it handy for baking or sweetening hot drinks. Unlike aspartame, which breaks down when cooked, saccharin holds on and keeps doing its job. For folks who like to make muffins or jams without sugar, there’s real value in a sweetener that doesn’t buckle when things heat up.

Health Facts and Common Concerns

People keep asking if artificial sweeteners are safe. In the 1970s, saccharin took a hit — studies back then linked it to bladder cancer in rats. That research led to warning labels that stuck on saccharin for years. Newer studies and reviews, including ones from the World Health Organization and the U.S. National Toxicology Program, haven’t found firm links to cancer in humans. Grocery store shelves no longer carry those warning labels.

Compared with sucralose or aspartame, saccharin doesn’t add calories or raise blood sugar. People with diabetes can safely use it. Unlike aspartame, which people with phenylketonuria have to avoid, saccharin doesn’t create any extra restrictions. Some folks may still have concerns, and the best approach is to talk these through with a registered dietitian or doctor. Clinical guidance shouldn’t come from social media hearsay but from credible studies and expert consensus.

Cost and Accessibility

One thing that stands out about sodium saccharin is the low cost. Aspartame and sucralose often cost more, both on store shelves and for manufacturers. If a family is shopping for a sugar substitute on a tight budget, saccharin can stretch the grocery bill a little further. In many developing countries, cost decides whether people can access sugar alternatives at all. Saccharin gets points for helping make lower-calorie options more widely available.

The Environmental Angle

Artificial sweeteners, including saccharin, end up in waterways, and their long-term effects on wildlife are still getting studied. Sucralose raises even bigger questions here because it breaks down slower than other sweeteners. The same intensity that makes these products economical also means small amounts travel far once they leave our homes.

Practical Solutions Moving Forward

For the millions of people who want less sugar but don’t want to give up sweetness, saccharin remains a strong choice — especially in countries where cost matters most. Clear, honest labeling and accessible information from responsible health authorities can help people make informed choices. Research should continue, especially as more sweeteners hit the shelves and new questions surface. For those trying to cut sugar, it’s not always about chasing the newest sweetener, but about finding the right fit for taste, safety, and budget.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium 1,2-benzothiazole-3(2H)-one 1,1-dioxide |

| Other names |

Saccharin Benzoic sulfimide o-Sulfobenzimide E954 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm ˈsækərɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | sodium 2H-1,2-benzothiazol-3(4H)-one 1,1-dioxide |

| Other names |

Benzoic sulfimide Saccharin Ortho-sulfobenzoic acid imide |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsoʊdiəm ˈsækərɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 128-44-9 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `sad(-1) c1cc2c(cc1S(=O)(=O)N)C=CS2` |

| Beilstein Reference | 105873 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:4344 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL267251 |

| ChemSpider | 157355 |

| DrugBank | DB00832 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.005.432 |

| EC Number | 128-44-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | 85234 |

| KEGG | C01739 |

| MeSH | D013190 |

| PubChem CID | 5237 |

| RTECS number | WS0925000 |

| UNII | WL7VP6O6HZ |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 128-44-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 2311043 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:43612 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201603 |

| ChemSpider | 6329 |

| DrugBank | DB02710 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.022.700 |

| EC Number | 128-44-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | 8492 |

| KEGG | C01716 |

| MeSH | D012446 |

| PubChem CID | 5237 |

| RTECS number | WN6500000 |

| UNII | F80MF9UJA2 |

| UN number | UN#3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C7H4NaNO3S |

| Molar mass | 183.18 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.828 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble |

| log P | -4.2 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 11.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.1 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.200 |

| Dipole moment | 3.16 D |

| Chemical formula | C7H4NNaO3S |

| Molar mass | 183.18 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.828 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble |

| log P | -3.4 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.1 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -12.0 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.333 |

| Viscosity | 30~100 mPa.s (20°C, 20% in water) |

| Dipole moment | 2.69 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 203.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -714.6 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -380 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 282.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -751.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -393.4 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A10BX04 |

| ATC code | A10BX04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H317 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: May cause eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry, well-ventilated place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Do not ingest. Use appropriate personal protective equipment. |

| Autoignition temperature | > 550 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 17,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 5000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Main hazards | May cause skin, eye, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements for Sodium Saccharin: "May cause eye irritation. May cause skin irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P264, P270, P301+P312, P330 |

| Autoignition temperature | > 550 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ Oral - Rat: 17,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | > 17 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | RN822 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Saccharin Calcium Saccharin Potassium Saccharin |

| Related compounds |

Saccharin Calcium Saccharin Potassium Saccharin Sucralose Aspartame |