Sodium Propionate: From History to Future Prospects

Historical Development

Sodium propionate entered the industrial world in the early 20th century, during a period when food preservation demanded better alternatives to naturally derived preservatives. Chemists started examining organic salts to slow down spoilage and discovered sodium propionate’s antifungal strengths. Bakeries and dairy producers adopted it quickly, recognizing its role in keeping bread mold-free longer during a time when reliable refrigeration remained out of reach for many. Regulatory approval arrived over the years in countries concerned both with food safety and shelf-life improvement, further solidifying its presence across processed foods. Behind every slice of shelf-stable bread, there’s a legacy of scientists racing against food waste and practicality shaping food science.

Product Overview

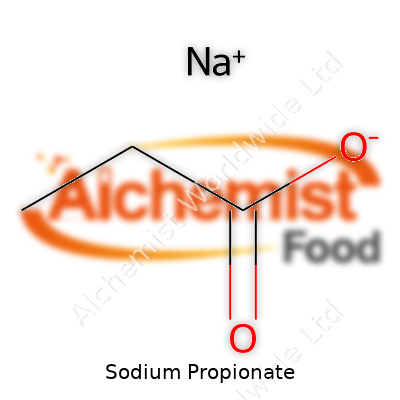

This white, powdery salt carries the chemical formula C3H5NaO2, crafted by neutralizing propionic acid. Food manufacturers value it for the way it prevents molds and some bacteria from blooming in flour-based goods, cheeses, and processed meats. Its E number—E281—helps consumers, regulators, and producers track its use in ingredient lists. Aside from food, sodium propionate makes its mark in pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and even animal feed, all thanks to its proven stability and safety track record across decades.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Sodium propionate forms a crystalline solid that dissolves keenly in water, giving it a practical edge for food applications. It’s practically odorless but gives off a faint, sharp scent when handled in bulk. At room temperature, it resists breaking down, but like other organic salts, it decomposes under high heat. The melting point hovers around 289°C. Its stability in food comes from its ability to lower pH locally and disrupt fungal metabolism, making it more effective in slightly acidic environments like bread dough.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

In commercial use, sodium propionate appears as a fine powder, granules, or compressed into tablets for specialty uses. Reputable producers hold purity above 99%, limiting contaminants such as heavy metals and residual acids far below international safety thresholds. Labels in packaged foods list it as “sodium propionate,” and sometimes reference its E number for regulatory clarity. In the US, it meets the “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) designation, reflecting its lengthy record of non-toxic use at recommended levels. For transportation and storage, food and chemical companies demand air-tight, moisture-resistant packaging; sodium propionate attracts water and will clump if left exposed.

Preparation Method

Factories produce sodium propionate through the direct reaction of propionic acid with sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide in aqueous conditions. The resulting brine gets filtered, and the product crystallizes out as water evaporates. Producers wash, dry, and mill the crystals before packaging and shipping to bakeries and factories. Most of the world’s propionic acid now comes from petrochemical sources, tying sodium propionate’s price to broader trends in energy and feedstocks, though research backs fermentation as a greener route for future production.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In water, sodium propionate splits into sodium and propionate ions. On the shelf, it holds up well, but under intense heat or acidic conditions, it may break down to release propionic acid or sodium compounds. Propionates play a role in organic synthesis, especially in the pharmaceutical industry, acting as starting points for more complex molecules. Chemists sometimes tweak the backbone for slow-release applications or greater microbial inhibition, aiming for additives that deliver broader protection or match specific formulation goals.

Synonyms & Product Names

Sodium propionate goes by several aliases in the chemical marketplace: “sodium propanoate,” “E281,” or “propionic acid sodium salt.” In pharmaceuticals and export markets, documentation may list CAS number 137-40-6 for universal clarity. These names help bilingual safety sheets, lab registries, and global trade logistics avoid costly confusion.

Safety & Operational Standards

Health authorities in the US, Europe, China, and elsewhere examined sodium propionate through toxicological studies, setting strict upper limits for foods and occupational exposure. Acute health risks for handlers stem from dust inhalation and skin contact, so plant workers rely on no-nonsense basics: gloves, dust masks, and eye protection. Outside the plant, bakers and consumers rarely face risk, since sodium propionate appears at tiny, measured concentrations. Governments periodically revisit standards as analytic tools sharpen, taking fresh looks at residue and purity benchmarks.

Application Area

Bakeries lead demand, sprinkling sodium propionate into dough mixes to stall the ever-present threat of mold, especially during warm, humid storage. Cheeses, especially processed varieties, take in sodium propionate to keep unwanted microbes at bay without affecting flavor. Meat processors employ it in prepared and cured meats for similar reasons, and animal feed producers use it to maintain quality through warehouse storage and shipping. Cosmetic chemists deploy it as a secondary preservative in lotions and creams, taking advantage of its mild profile. In medicine, it sometimes stabilizes ingredients in specialty tablets and suspensions.

Research & Development

Researchers look for ways to reduce energy and petrochemical use in sodium propionate synthesis. Fermentation from renewable biomass enters pilot trials, with certain bacteria breaking down sugar-rich waste into propionic acid, sidestepping dependence on oil. In food science, microbiologists screen for new spoilage organisms that resist sodium propionate, hoping to keep one step ahead in the preservative arms race. Academics examining consumer health interests publish findings showing low allergenic potential and no links to major chronic health problems, allaying bakers’ and shoppers’ anxieties. New analytical tools allow more sensitive purity checks, raising the bar for bulk producers trying to enter premium markets.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists continue to probe whether long-term consumption of sodium propionate in food correlates with health risks, especially among sensitive groups. Most studies, including large-scale feeding trials in rodents and primates, report no carcinogenic, reproductive, or developmental trouble at levels far above what foods typically contain. Metabolically, it breaks down into compounds the body handles easily, passing through without lingering or cumulating in tissues. Occasionally, case reports surface of individuals experiencing mild digestive upset, but these result from ingesting doses much higher than those found in bread or cheese. Regulatory bodies across developed markets keep re-evaluating old and new data, sometimes prompting tweaks in recommended daily intake.

Future Prospects

As food supply chains stretch and calls for reduced waste grow louder, the story of sodium propionate only expands. Producers feel the pressure to embrace green chemistry and shed fossil-fuel dependencies, putting fermentation or bio-based routes front and center in R&D budgets. Scientists working on “clean label” foods confront the challenge of reducing synthetic-sounding additives, posing fresh hurdles for sodium propionate if consumers’ perception shifts. New research takes a closer look at how combinations of propionates and other natural preservatives work together to limit spoilage while meeting customer demands for minimal-processing and clear labeling. Advances in food packaging—engineered to extend shelf life using less chemical input—also shape the outlook, hinting that sodium propionate’s role will need to keep evolving with technology and taste.

What is Sodium Propionate used for?

What Sodium Propionate Really Is

Sodium propionate turns up on lots of ingredient labels, right next to the expiration date. You’ll see this compound in bread, cakes, and a bunch of processed foods in the grocery store. At its core, sodium propionate keeps mold and bacteria from taking over what you eat.

Mold Prevention on the Dinner Table

Bakeries and big food companies rely on sodium propionate because mold causes enormous losses every year. One spoiled loaf can mean several wasted, and where you have mold, you often have a few health worries too. In countries where hot weather speeds up spoilage, this ingredient helps bread stay good for days, saving stores and families money. In my own kitchen, I’ve seen homemade bread go moldy in less than two days, but a store-bought loaf with sodium propionate stays fresh much longer.

How It Works in Your Food

Sodium propionate controls the pH and stops the enzymes that molds use to spread. Scientists discovered long ago that this chemical fights off fungal growth, and it’s no secret why commercial bakeries use it. Food safety agencies, including the FDA, give sodium propionate a green light as a preservative in reasonable doses. If you check the science, its action against spoilage makes a real difference in keeping food edible.

Safety and Concerns

Food additives raise tough questions, and sodium propionate isn’t immune. Some people worry about anything “chemical” in their food, often after headlines link additives to health problems. Current evidence suggests this compound breaks down into substances your body deals with every day—after all, it’s similar to what’s in many cheeses naturally. Occasionally, sensitive guts might react with mild irritation, but these cases seem rare. Honest labeling matters. Shoppers want transparency, and knowing what's in food can guide better decisions for sensitive individuals.

Where Else It Shows Up

Though sodium propionate pops up in baked goods most often, manufacturers also add it to processed meats and cheeses. It’s less common in other food categories since its main job targets mold that feasts on flour and dairy. Sometimes, animal feed producers use it to keep livestock grains safe, cutting down loss from spoilage.

Bigger Picture: Preserving Food and Reducing Waste

My years writing about food have shown time and again that food waste remains a stubborn problem. Preservatives like sodium propionate let families and stores stretch the life of groceries, leading to fewer trips to the store and less food in the trash. Tossing less bread or cake isn’t just good for wallets—it eases the pressure on landfills too.

Balancing Needs and Choices

If you feel cautious about preservatives, switching to fresh local bread is always an option, but you’ll need to eat it fast. On the flip side, long shelf life has practical perks, especially in places with limited food access or hotter climates. Trustworthy, up-to-date research should remain at the center of future food decisions. Asking manufacturers for clear, simple labels can make a big difference in how confident shoppers feel. Awareness and transparency will keep conversations about food additives honest and helpful.

Is Sodium Propionate safe to consume?

Breaking Down What Sodium Propionate Actually Is

Sodium propionate shows up in lots of food labels, particularly in baked goods, processed cheese, and some desserts. Manufacturers use this ingredient because it keeps mold from forming, making food last longer on store shelves. I’ve gone through my fair share of food science seminars, and sodium propionate always comes up during discussions of food safety, shelf life, and preservatives.

The Science Behind Its Safety

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) calls sodium propionate “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS). The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and many top food scientists worldwide share this viewpoint. These designations don’t get handed out lightly. Scientists run animal studies, comb patient health surveys, and set daily limits to keep consumption safe. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives did extensive reviews and laid out safe intake levels. Most people eating a typical Western diet end up nowhere near these limits.

I’m comfortable eating bread or pastries that list sodium propionate, not just because of regulatory thumbs-up, but because adverse effects rarely crop up in healthy individuals eating standard portions. Some people claim preservatives upset their stomach. For most, the link hasn’t shown up in well-run research. There’s also concern about hyperactivity in kids, but studies around propionates haven’t demonstrated consistent risks.

What Happens Inside the Body?

Once someone eats sodium propionate, the body breaks it down into propionic acid. Our gut needs to process lots of acids, especially after eating fiber-rich foods, so this isn’t unusual. The gut bacteria even make their own propionic acid from digesting certain plant fibers. The kidneys and liver quickly filter the extra, pushing it out with regular urine waste. That keeps any buildup from happening under regular dietary conditions.

Concerns About Long-Term Consumption

Even though regulatory agencies say sodium propionate is safe, people sometimes worry about eating chemicals they can’t pronounce. Some online posts talk about possible links between propionates and metabolic issues or gut health. Looking through peer-reviewed journals, high doses in animal studies sometimes triggered changes in insulin response or behavior. The catch is that those animals received way more of the chemical than anyone would ever eat from food. A regular sandwich or muffin doesn’t pack enough to cause the same effects.

One point I always raise in public lectures is the difference between “dose” and “danger.” A sprinkle of table salt makes food taste good, but too much salt every day might put blood pressure at risk. Sodium propionate ends up in relatively tiny amounts, definitely less than what’s shown to cause problems in any real-world dietary surveys.

Room for Better Transparency

Many people want easier-to-read food labels and resources about exactly what goes into their meals. More manufacturers today offer preservative-free choices or clearly list every additive in plain language. That helps families make decisions based on their own health needs or beliefs. If you have a food allergy or unique health condition, a conversation with a physician or registered dietitian helps clarify any special risks.

There’s always room for more independent research on food preservatives, particularly for long-term and vulnerable groups such as children. Supporting unbiased studies and sharing results widely will help foster trust and keep everyone safer.

What are the side effects of Sodium Propionate?

What Is Sodium Propionate?

Sodium propionate shows up in many ingredient lists, especially on processed foods like bread, pastries, and some dairy goods. Its job is to keep products from turning moldy or spoiling too fast. Many people eat foods containing this preservative every week without giving it much thought. The FDA recognizes sodium propionate as generally safe for use in food, but some people care about even low risks, especially if eating packaged food is a daily thing.

Common Side Effects and Sensitivities

Some people report digestive issues when eating foods high in preservatives. With sodium propionate, stomach upset, nausea, or a bit of cramping can pop up in sensitive people. Kids with certain food sensitivities have shown behavioral changes after eating foods heavy in preservatives, including propionates. The science isn’t solid on this point—some studies point toward a link, others don’t. Parents worried about hyperactivity sometimes keep an eye on any food triggers, preservatives or otherwise.

Allergic Reactions and Rarer Concerns

Allergies to sodium propionate show up less than to additives like sulfites, but reactions do exist. Rashes, swelling, or difficulty breathing call for a doctor’s care, no matter the cause. People with asthma sometimes find symptoms worse after eating foods with certain preservatives, including sodium-based ones. Asthma rates keep rising, so people learning which foods help or hurt matters for daily quality of life.

Long-Term Exposure: What Studies Say

Europe’s food agencies reviewed propionic acid’s safety along with its sodium salt. Their research points to low risk at the amounts usually found in food. Still, researchers are digging into what happens when someone eats processed snacks and meals day after day. Some animal tests saw stomach lining irritation at levels much higher than in bread or cheese, but humans don’t experience those doses from a regular diet.

Processed food delivers a lot of preservatives if it makes up most of someone’s meals. Folks eating this way can see changes in gut bacteria—and gut health ties strongly to overall wellness. Scientists continue debating just how much change comes from the preservative or from the rest of the processed food package.

Tips for Reducing Side Effects

Baking at home gives full control over what goes into bread and baked goods. People who notice they feel better on “cleaner label” diets might look out for sodium propionate as one more ingredient to skip. Reading labels closely and learning which brands use fewer preservatives offers another tool. For families managing allergies or asthma, talking with a dietitian can help zero in on foods that play well with their health needs.

Ways Industry Can Respond

More consumers ask for food with fewer additives. Some bakers and brands choose natural acids like vinegar to keep products fresh, or develop packaging that protects against spoilage without chemical preservatives. Open conversations between companies and shoppers have driven new formulas with familiar pantry ingredients. Feedback from shoppers shapes store shelves, nudging brands to rethink how they keep food safe and tasty.

Relying on Real-World Choices

Some folks never notice a problem from sodium propionate and comfortably eat foods containing it. Others notice subtle changes and prefer to minimize their intake. My own experience lines up with the research—not everyone reacts, but reading labels matters if you live with health conditions influenced by diet. Sticking closer to home-cooked meals made with whole ingredients usually brings peace of mind and fewer worries about what’s hiding in small print.

Is Sodium Propionate a preservative?

Recognizing Sodium Propionate’s Real Role in Food

A lot of people glance at bread labels, stumble on “sodium propionate,” and start to wonder what it’s actually doing there. Food labels have a knack for sending us to the internet or a dictionary. Years ago, I found myself checking every ingredient after being spooked by a news story about food additives. Out of curiosity, I looked up sodium propionate, hoping for a straightforward answer. Turns out, it deserves more than a suspicious side-eye from shoppers and parents.

Preserving Food, Not Mystery

Sodium propionate stands square in the food world as a preservative. That isn’t some food industry trick or clever marketing—it’s science. Bread, pastries, tortillas, and dairy foods attract mold faster than a sinkful of dirty dishes. Sodium propionate doesn’t hide or disguise; it shows up for one reason: stopping mold growth. Microorganisms like mold thrive in moist bread. A slice exposed to air even for a day or two can sprout blue or green fuzz in no time—unless preservatives break that cycle.

Research from the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) and scientific reviews consistently recognize this compound’s mold-fighting ability. The FDA lists sodium propionate as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) in baked goods within specific limits. The chemical blocks the enzymes molds use to grow, breaking the cycle before it even starts.

Safety, Trust, and Transparency

It’s easy to assume that everything unpronounceable in the ingredients list is a threat. As a parent and a cook, I want to know what goes into my food, not just for my family’s sake but out of sheer curiosity. The truth is, sodium propionate doesn’t build up in the body, nor does it linger longer than needed. It breaks down in the body similarly to other natural salts, exiting with standard metabolic waste. The amounts added to bread and dairy fit FDA and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) standards.

Allergies and intolerances are always possible with anything, but sodium propionate rarely makes headlines in this area. Still, more food companies post information about their processes and ingredient sourcing now than a decade ago. If there’s genuine concern about any preservative, asking your grocery store bakery or food supplier doesn’t hurt.

Weighing Benefits and Seeking Alternatives

Fewer preservatives may sound ideal, but anyone who has found a forgotten fresh loaf sprouting colonies overnight knows how quickly quality can vanish. Store shelves would shrink without preservatives because products would go stale and moldy in days, not weeks. Cutting food waste means striking a balance between shelf life and minimizing chemical intake.

Some companies test natural mold inhibitors like vinegar or cultured wheat flour. Artisan bakeries that skip chemical preservatives usually bake in small batches and recommend eating bread quickly. These small adjustments prove that while alternatives exist, they can’t always match the convenience or safety net provided by more established preservatives.

Building an Informed Perspective

Sodium propionate keeps baked goods and dairy safer for longer. As with all food choices, the final call rests in consumers’ hands. Reading labels, tracing ingredient origins, and talking with food producers offers more assurance than a quick online search. Science backs its use, and experience in kitchens and grocery aisles shows its value daily. Focusing on fact-based information instead of fear helps everyone make food choices they can stand behind.

Can Sodium Propionate cause allergies?

What’s Sodium Propionate Doing in Your Food?

Sodium propionate keeps food fresher longer — you’ll spot it on ingredient lists for bread, cakes, processed cheese, and some ready-to-eat meats. The main reason for its use: it stops mold growth. Nobody wants moldy bread, so this additive gets heavy use in bakeries and supermarkets across the world. It’s approved by food safety authorities in the U.S., Europe, and many other countries, partly because scientists have found it safe for most people to eat in small quantities.

Where Do Allergy Concerns Come From?

People often worry about chemicals in food, and that’s not crazy given how many folks have allergic reactions to common additives like sulfites or artificial colors. The thing about sodium propionate — it’s much less known for triggering allergic responses. Most clinical data points out that true allergic reactions to this compound are rare. If anything, vomiting, stomach pain, or nausea get reported more often than any classic signs of food allergy like hives or breathing problems.

Some people with extremely sensitive stomachs, especially kids, report abdominal discomfort after eating products rich in food preservatives, sodium propionate included. In most documented cases, this is discomfort or intolerance, not a full-blown immune response. Allergists know what true allergy looks like: hives, swelling, wheezing. Most cases tied to sodium propionate land on the side of irritant effects, not immune-based allergies.

The Science Behind the Claims

The FDA allows sodium propionate based on decades of toxicology work. The European Food Safety Authority reviewed propionates again in the last few years and kept them on the approved list, noting the lack of proven allergenic effects even at levels found in commercial food. One thing these authorities emphasize: even if a handful of people don’t tolerate this additive, the odds of a life-threatening response seem extremely low.

As someone with eczema and a family history of food allergies, I’ve had to dig into ingredient labels and sometimes track symptoms for weeks to spot any real trigger. Bread with sodium propionate never caused me or my family a problem, but I know how real food anxiety can be. Data from medical research and allergy clinics backs this up — confirmed propionate allergies barely make the medical literature.

Possible Solutions for Those with Concerns

People with ultra-sensitive stomachs may still want to limit foods with many preservatives. If nausea or stomach upset hits after eating certain packaged goods, keeping a food diary and checking food labels helps. Trying preservative-free bread from small bakeries can be a workaround for those who don't want to risk it. If an allergy is genuinely suspected, seeing an allergist for specific testing beats self-diagnosing.

Building Trust in Food

Misinformation and scary headlines make people anxious about food they buy every day. Reading scientific reviews and talking with food allergy specialists helps take some worry out of eating. The numbers don’t show sodium propionate as a likely trigger for serious allergies, but it’s never wrong to advocate for clear labeling and more choices. Everyone deserves to know what’s in their food and choose what works for their health.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium propanoate |

| Other names |

Propanoic acid sodium salt Sodium propanoate E281 Propionic acid sodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˌsoʊdiəm proʊˈpioʊneɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium propanoate |

| Other names |

Propionic acid, sodium salt Sodium propanoate E281 Propanoic acid sodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˌsəʊdiəm prəˈpəʊni.eɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 137-40-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1907001 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:31346 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1356 |

| ChemSpider | 6819 |

| DrugBank | DB11062 |

| ECHA InfoCard | '03b6928d-62d0-4d66-8402-97d8c5b82fbd' |

| EC Number | EC 204-623-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 3155 |

| KEGG | C01822 |

| MeSH | D011379 |

| PubChem CID | 517055 |

| RTECS number | UB4050000 |

| UNII | X9T41D21KB |

| UN number | UN1455 |

| CAS Number | 137-40-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 715873 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:31346 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1355 |

| ChemSpider | 5485 |

| DrugBank | DB02704 |

| ECHA InfoCard | '03b7c9b2-1233-4d8c-89ae-4c2a8fb971d8' |

| EC Number | 203-769-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 1866 |

| KEGG | C01822 |

| MeSH | D011379 |

| PubChem CID | 517055 |

| RTECS number | UF6970000 |

| UNII | X9U1FOK69T |

| UN number | UN 2813 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H5NaO2 |

| Molar mass | 96.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.26 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Easily soluble in water |

| log P | -0.38 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa 4.87 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.00 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -30.9·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.432 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | C3H5NaO2 |

| Molar mass | 96.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.59 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -0.38 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa 4.87 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.09 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -24.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.430 |

| Viscosity | 50 - 100 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 2.64 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 120.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -576.3 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2076.7 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 160.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -631.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2075.1 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A01AB19 |

| ATC code | A07AA07 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause mild skin and eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 250°C |

| Autoignition temperature | > 440 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3730 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral (rat) 3730 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WFZ2C96E67 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Sodium Propionate: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 300 mg/kg |

| Main hazards | May cause irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 250 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | > 462 °C (864 °F; 735 K) |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 4970 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat 3970 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WH2600000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Sodium Propionate: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 300 mg/kg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Propionic acid Propionyl chloride Potassium propionate Calcium propionate |

| Related compounds |

Propionic acid Propionates Calcium propionate Potassium propionate |