Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite: A Deep Dive into an Industrial Staple

Historical Development

Sodium hydrogen sulfite, often called sodium bisulfite or by its chemical formula NaHSO3, traces its roots back to the progress of industrial chemistry in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Chemical giants looked for ways to control oxidation and manage unwanted discoloration in food, textiles, and pulp products. In those early days, companies relied on crude production that involved bubbling sulfur dioxide through sodium carbonate solutions, a process that cemented sodium hydrogen sulfite’s importance as both a preservative and an antioxidant. The demand for more reliable and consistent formulations led suppliers to fine-tune production techniques, and countries invested heavily in infrastructure that provided access not just to source materials but to specialists who could refine the yield and purity of sodium hydrogen sulfite crystals. Modern facilities now generate sodium hydrogen sulfite on a commercial scale, supporting massive food and water treatment markets worldwide.

Product Overview

Sodium hydrogen sulfite, or E222 as the food industry calls it, shows up in everything from packaged fruits to municipal water. Its key strength lies in scavenging oxygen and neutralizing chlorine, all while occupying a small but mighty role as a preservative. Manufacturers offer it in powder and solution forms, allowing broad adoption in applications that include cleaning, water disinfection, and chemical synthesis. The product usually travels in sealed, moisture-proof packaging, as it attracts water and gives off sulfurous odors when left exposed. Buyers value sodium hydrogen sulfite not for romance or flash, but for persistence and effectiveness. Food processors need its predictable behavior to prevent browning, winemakers add it to stabilize and clarify fermentation, and industrial users trust it to quench residual chlorine after water sterilization.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Sodium hydrogen sulfite forms white or yellowish solid crystals, highly soluble in water but not in most organic solvents. Its molecular weight clocks in just over 104 g/mol. Strong humid conditions cause the powder to clump and release an unmistakable sour smell, a direct result of sulfur dioxide emissions. In water, sodium hydrogen sulfite produces mildly acidic solutions, usually in the 4-5 pH range. Its melting point runs lower than one might guess, sitting around 150°C, as it breaks down before reaching a full melt. Its interaction with oxidants brings rapid reaction and is part of why it sees wide use as a reducing agent. Someone handling the powder will quickly notice the sulfur smell that seems to stick to your hands and clothing, a tell-tale sign that the material is both reactive and volatile in humid air.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers list sodium hydrogen sulfite under several grades, targeting food, industrial, or laboratory use. Labeling must follow precise regulations, showing purity—commonly 97% or better—alongside any stabilizers or anti-caking agents. Technical datasheets outline sulfur dioxide content, moisture levels, bulk density, and solution clarity. Any reputable supplier discloses impurity levels, especially metals like iron or arsenic, since end-users in food manufacturing face tight legal standards. Label warnings on packaging focus on dryness, ventilation, and avoiding direct sunlight. Packed in plastic-lined drums or polyethylene bags, product codes will often reflect batch numbers, expiration dates, and the intended market to prevent confusion at points of use. The need for traceability has only grown stronger, and digital records now help guarantee batch recall and regulatory compliance.

Preparation Method

Industrial production calls for precise conditions. Plants draw on sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide, injected with sulfur dioxide gas until the correct sodium hydrogen sulfite salt forms. The mixture cools, and excess liquid decants or evaporates, leaving the bisulfite behind. Controlling temperature and sulfur dioxide flow—no simple trick—means plant engineers must monitor each step, making sure they avoid side reactions that would eat into product purity. Small labs sometimes make sodium hydrogen sulfite in situ, but commercial users want bulk consistency, so companies turn to continuous reactors and highly automated systems. Attention to gas-phase mixing, solution concentration, and temperature all factor into yield and crystal size, supporting a dependable supply chain.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Sodium hydrogen sulfite reacts with strong acids to liberate sulfur dioxide, which is a key intermediate for sulfur-based syntheses. It reduces permanganates and halogens, making it a popular dechlorinator in pool and water treatment, and will break down aldehydes and ketones in pharmaceutical manufacturing. When solutions get exposed to air, oxidation gradually converts bisulfite to sulfate or thiosulfate. Chemists can modify sodium hydrogen sulfite with stabilizers to slow this process. In personal experience, throwing it into a chlorinated rinse tank at the wrong concentration leads to either a rapid, violent reaction or incomplete dechlorination—a risk always present without proper titration.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll find sodium hydrogen sulfite listed as sodium bisulfite, monosodium sulfite, and even by its E-number, E222, in food applications. Across water treatment and industrial cleaning, documentation may show alternative names, but the chemistry stays constant. In older texts and supplier catalogs, different countries stick to local language variants, and global buyers need familiarity with product codes, not just the main chemical name, so shipments do not get delayed by mislabeling.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone handling sodium hydrogen sulfite has to pay close attention to personal protection. Skin and eye contact brings intense irritation and, much worse, inhaling dust or vapors can set off respiratory trouble, especially in people with asthma or other lung conditions. Industrial sites must implement solid standard operating procedures and keep eyewash stations and gloves close at hand. Local exhaust systems remove stray fumes, and dry areas help keep the material stable. Storage always happens in sealed containers and away from strong oxidizers. Current regulatory heat puts a spotlight on safe handling through training and documentation, and many plants mandate spill containment kits. After several years on a mixed-use site, it becomes clear that the right labeling and proper separation from acids prevent not just accidents but disastrous releases of sulfur dioxide.

Application Area

Food preservation stands out as one of the most familiar uses, keeping dried fruit and shellfish looking fresh and palatable during long transits and shelf life. In winemaking, sodium hydrogen sulfite is irreplaceable for stabilizing freshly pressed grape juice, halting wild fermentation, and clarifying product before bottling. Water treatment operators put it to work neutralizing residual chlorine before water heads into sensitive fish habitats or food plants. Pulp and paper lines employ it to bleach and prevent buildup of undesirable side products while cleaning up wastewater. Textile processors depend on sodium hydrogen sulfite to remove excess dye and correct color issues during production of cotton and wool fabrics. Some medical applications, notably in hemodialysis or as a chemical intermediate, further highlight its wide reach. Each application requires a careful match of grade and dosage, making consultation with suppliers and regulatory bodies vital to keeping product quality and safety up to snuff.

Research & Development

Academic labs and industry groups keep plugging away at boosting the stability and reactivity of sodium hydrogen sulfite products. Research in the last decade honed in on shelf life improvements, granular formulations that resist caking, and low-dust mixtures to improve worker safety. Analytical chemists focus hard on refining test methods for trace contaminants, pushing detection limits lower each year. Enzyme and pharmaceutical development explores new ways to harness the compound’s reducing power while controlling byproducts. My own experience in industry collaborations shows that process engineers get the best results by working with research chemists, who approach both purity and sustainability as design targets. Progress relies not only on lab breakthroughs but on translating them through pilot trials to the men and women mixing tanks and running lines on the factory floor.

Toxicity Research

Extensive toxicological reviews make clear that sodium hydrogen sulfite exhibits moderate acute toxicity if inhaled, swallowed, or heavily exposed to the skin. Chronic exposure brings a risk of developing allergic reactions or asthma-like symptoms, especially in workers with regular, unprotected contact. Animal studies confirmed low potential for carcinogenicity, but ingestion in high amounts—the sort not seen from a typical meal—provokes headaches, nausea, or worse. Food safety authorities set strict limits on what’s acceptable in prepared foods, usually no more than 100-200 mg/kg in dried fruits and wines. Environmental scientists warn about uncontrolled releases into aquatic systems where sodium hydrogen sulfite can deplete oxygen and endanger fish. Personal encounters underscore the importance of timely cleanup and air checks wherever handling may lead to accidental releases. Regulatory frameworks keep companies honest, so routine monitoring programs remain the norm today.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, consumer and industry shifts continue to shape how sodium hydrogen sulfite features across manufacturing. Clean label trends in food make some companies seek alternatives, but for many bulk preservation applications, sodium hydrogen sulfite remains tough to beat. Advances in packaging and dosing equipment may cut down worker exposure and waste. Environmental policies could push for closed-loop water treatment and tighter emission controls, leading to further refinement of both product purity and process safety. Digital labeling and blockchain tracking of raw materials already help raise confidence in product history, and the next wave of innovation promises better traceability and transparency for end-users up the supply chain. Research into low-sulfur dioxide byproducts or bio-based alternatives may give sodium hydrogen sulfite a run for its money, but sheer economic efficiency keeps it relevant in today’s cost-sensitive markets. Those working hands-on with the material know that while tweaks and improvements arrive, the basic chemical continues to anchor industries that rely on trusted, robust chemical solutions.

What is Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite used for?

The Chemistry of Day-to-Day

The name sodium hydrogen sulfite doesn’t naturally roll off the tongue, but many households and factories depend on it more than you’d expect. I spotted the name the first time in a food ingredient list years ago, tucked underneath ingredients I thought I already understood. This compound keeps popping up in places where preservation, cleaning, or quality control comes into play.

Keeping Food Fresh and Safe

Most folks trust that what lands on grocery store shelves is safe. Sodium hydrogen sulfite helps here by acting as a preservative. Packaged foods, especially those with dried fruit, wine, or processed potatoes, often turn out looking unappealing if left without protection. Browning and spoilage follow quickly when oxygen has free rein. This compound slows that down. I learned this the hard way after baking a large batch of homemade apple rings — those without proper preservation browned and toughened fast. Industries use sodium hydrogen sulfite to block enzymes responsible for discoloration. Not only does this keep food safer for longer, but it also cuts down on waste.

Making Wine and Juice Taste Right

Few traditions bring people together quite like sharing a drink. During winemaking, fermenting grape juice sometimes produces off-flavors or unwanted bacteria. Sodium hydrogen sulfite pops in right here as a powerful sanitizer and antioxidant. By taming wild yeasts or bacteria, it preserves the wine’s intended taste. Professional wine-makers carefully adjust their dosages to avoid ruining flavor. Home brewers who skip it learn quickly that contamination brings a sour disappointment. Food safety agencies set clear limits, protecting sensitive individuals, especially those prone to asthma who could react to the sulfites.

Cleaning Up in the Lab and Beyond

Digging through memories from my college chemistry courses, sodium hydrogen sulfite played a role nearly every time we had to clean up after experiments. It breaks down chlorine and peroxide residues. Water treatment plants use this property, neutralizing chlorine before releasing water back into nature. Pulp and paper factories rely on this reaction too, using it to bleach paper without leaving harmful byproducts behind. Though the chemistry seems simple, the benefits stack up — safer water, whiter paper, and less pollution.

Risks, Regulation, and Looking Forward

Every tool comes with trade-offs. Overuse or improper handling of sodium hydrogen sulfite can trigger health worries. Sensitive individuals sometimes develop allergic reactions. Nausea and breathing difficulties show up among those who handle the compound without proper protective gear. As a society, I’ve noticed regulations tighten over the years; the FDA and EPA continually review approved uses and exposure limits. The food industry clearly labels products with sulfites, helping people make informed choices.

Alternatives like ascorbic acid or nitrogen flushing offer some similar protection, and they’ve gained popularity among those avoiding chemical preservatives. Still, sodium hydrogen sulfite persists because of its reliability and low cost. Businesses and researchers monitor its downsides, looking for ways to minimize risk while protecting its benefits.

Trust, Transparency, and Taking Action

Sound food systems and environmental practices start with knowing what’s added and why. Sodium hydrogen sulfite’s work behind the scenes shows how chemistry can improve daily life, but its downsides can’t be ignored. By supporting open labeling, sensible regulation, and a culture of informed choice, we strengthen public trust and look out for those most at risk.

Is Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite safe to handle?

Everyday Encounters With Chemistry

I’ve spent enough time in science labs and working around industry folks to know that no matter how fancy or technical a chemical may sound, the same question crops up every time: is it safe? Sodium hydrogen sulfite, which some know as sodium bisulfite, shows up in a surprising number of places—from water treatment to winemaking.

In small doses, sodium hydrogen sulfite does a job society relies on. It helps keep water clean, preserves foods, and gets rid of unwanted chlorine. But people handling it outside controlled settings can run into trouble if they treat it casually. The issue isn’t so much about what this compound does in theory, but how it interacts with skin, eyes, lungs, and whatever else it touches along the way.

The Risks That Don’t Disappear

If you’ve ever opened a bag of the stuff and caught that nose-wrinkling whiff, you’ve picked up on the real hazard: fumes. Sodium hydrogen sulfite can release sulfur dioxide, and that gas can sting your eyes, throat, and lungs. People with asthma or any breathing condition get hit even harder. Breathing in enough can mean headaches, coughing, and chest tightness. In some work environments, a few moments of carelessness can lead to emergency room visits.

Most people underestimate the other risks until they see chemical burns—direct contact with skin can cause itching, redness, or serious rashes. I’ve watched a new lab tech touch the salts and wound up scrambling for the eyewash after rubbing his eyes. The label might warn about trouble, but those words don’t sink in for everyone until it’s too late.

What the Experts Advise

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration lists sodium hydrogen sulfite as hazardous. Storage instructions stress cool, dry spots away from kids and food. Gloves and goggles beat wishful thinking—barriers between skin and chemical prevent most accidents. Decent ventilation trumps open doors and windows, especially in smaller spaces. Medical studies say the folks most at risk are workers in food processing plants and cleaning crews, not the scientists in lab coats.

Some winemakers swear by this compound for fermentation, but they handle it using gear and clear routines. They watch for bottle labels, keep spill kits handy, and train staff to rinse skin right away in cool water after a mix-up. Anyone handling the powder on an industrial scale knows safety isn’t a formality, it’s real protection from real harm.

Solutions That Don’t Rely on Luck

Companies need to set standard operating procedures—policies don’t just exist for paperwork. Training goes beyond watching a video once a year; people need to practice with real materials in the conditions they’ll face on the job. I’ve met people who skip the gloves one day and pay for it for weeks afterward.

For people at home, always check what’s actually in the products you’re using. Read the small print, keep products away from food, and store them away from children and pets. Spill something? Don’t use your bare hands to clean it up. Baking soda and water work to neutralize small spills, then plenty of water for cleanup. If anything gets in your eye or on your skin, flush it right away and call for help.

The big takeaway from my own bumps and scrapes: safety rests on good habits, not luck. Chemicals like sodium hydrogen sulfite are only as safe as the person using them decides to be.

What are the storage requirements for Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite?

Looking at Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite

Sodium hydrogen sulfite, better recognized in some places as sodium bisulfite, frequently shows up in labs, water treatment, and food processing sites. It serves as a preservative, bleaching agent, and reducing agent. I’ve moved buckets and drums of this stuff in both university settings and during a stint at a municipal water plant. Despite the usefulness, the headaches come when you ignore how picky it is about its environment. Every worker who’s torn into a bag or opened a drum of sodium hydrogen sulfite will tell you: moisture, heat, and contamination spell trouble fast.

Moisture and Air: The Unseen Thieves

Humidity transforms sodium hydrogen sulfite from solid to clumpy mush. Left unchecked, it reacts with air and pulls moisture straight out of it. Along with water vapor, oxygen in the air nudges it towards breaking down, creating sulfur dioxide gas. Anyone in a small storeroom can tell when those invisible changes start—the smell gets harsh, sometimes it stings your throat, and the eyes might water. Containers have to stay sealed tight, not just loosely capped. I’ve seen good money wasted when a cap was left off a barrel for just a weekend, turning part of the supply into useless crust.

Containers Matter—a Lot

Plastic drums or high-grade polyethylene containers work. Metal gets eaten through, especially with repeated exposure. Cheap buckets or thin liners end up failing because the material can’t hold back moisture or comes apart after shaking. For small labs, original supplier packaging should stay intact as long as possible. Big plants use drums with special gasketed lids, and they use pallets to keep everything off bare floors. Once a container sits on concrete, condensation builds underneath, attacking the container itself.

Heat Is Not a Friend

Heat speeds up decomposition and vaporizes sulfur dioxide. Storing the chemical near boilers, direct sunlight, or even in warehouses with poor cooling leads to rapid spoilage and health risks. Sulfur dioxide irritates the lungs, especially if the exhaust system isn’t moving a lot of air. I’ve seen staff develop headaches in old storerooms where air conditioning cut out and nobody noticed until the smell got tough to ignore. The maintenance team at our water plant checked temperature gauges by touch, not just numbers—hands told them if a room ran too warm for safe storage.

No Chance for Food or Metal Nearby

Warehouses that share space with foodstuffs or metals court disaster. The chemical contaminates grains, sugar, and other absorbent materials even through accidental dust. Metal corrosion can wreck shelving and add impurities to stored product. Rust and sodium hydrogen sulfite don’t mix cleanly, producing off-color powder and hazardous spots. Dedicated shelves, with no sharing between cleaning tools and chemical bins, keep everything isolated and out of trouble.

Training and Emergency Measures

It’s not enough to just lock sodium hydrogen sulfite away. Anyone who opens containers or shifts storage locations should know the signals of a leak or decomposition—sharp odor, crusting, hissing gas. Proper gloves and face shields guard against splashes or accidental contact. Many chemical storerooms now list emergency numbers right on the door and keep spill cleanup kits stocked and checked. Chlorinated cleaners stay clear, since they can react violently with small spills.

Smarter Practices for a Safer Workplace

These habits grow from hard lessons and a handful of near-misses: label everything clearly, keep inventory rotation steady to use older stock first, and review storage sites at least once a shift, especially in busy seasons. Safety isn’t just about regulations—it’s about preventing the waste, cleanups, and risk to people that show up when you cut corners storing sodium hydrogen sulfite.

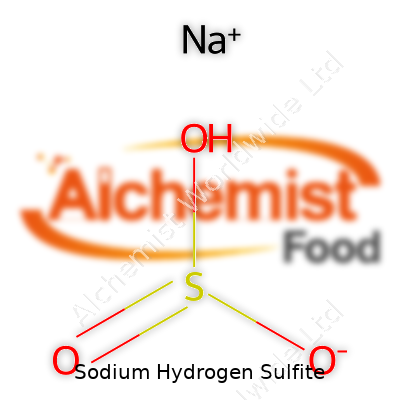

What is the chemical formula of Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite?

A Simple Formula With Everyday Impact

Sodium hydrogen sulfite carries the chemical formula NaHSO3. It’s not the kind of compound most folks think about while making coffee in the morning. Still, this simple mix of sodium, hydrogen, sulfur, and oxygen shows up in more places than some realize. Sitting on the shelf as a white powder or sometimes dissolved in water, sodium hydrogen sulfite doesn’t call attention to itself, yet it plays a bigger role than its plain name suggests.

Why NaHSO3 Matters Beyond the Lab

Take a walk through a food processing plant, and you spot the steady hands of workers tossing in sodium hydrogen sulfite to help preserve dried fruits or to keep color and freshness in vegetable packs. As a preservative, it drops pH levels enough to discourage unwanted bacteria from setting up shop. In real life, keeping food safe for transport matters to everyone involved, from farmer to grocery shopper. The sharp tang of sulfur it leaves means it’s doing its job, holding off spoilage and keeping costs from creeping up.

Having worked in a small winery, I’ve watched NaHSO3 save batch after batch of white wine from going brown. Winemakers reach for it during fermentation and bottling. They rely on it not only for its ability to snuff out wild yeasts but also to protect against oxidation, giving bottles a chance to age gracefully. Without that intervention, more bottles end up spoiled, and less wine reaches the table. It feels good to trust that safety net.

Safety and Environmental Questions

Not everything about NaHSO3 lands in the win column. Breathing the dust or its fumes can trigger asthma or irritate eyes and lungs. One close call can stick with you—gloves, goggles, masks become less an afterthought and more a routine necessity. Mistakes cost time and safety. Factories address this with strict handling protocols and regular safety training. Everybody on the floor should know what that faint sulfur smell means.

This chemical’s journey doesn’t end at the point of use. Runoff or heavy use brings environmental worries. Spilling it into rivers or soil upsets delicate balances, harming fish and plant life. In many areas, regulations set upper limits on discharge and require proper neutralization before leaving the plant. I’ve seen companies turn to waste treatment specialists who neutralize the chemical with alkaline solutions, keeping it from causing downstream damage.

Toward Better Solutions

It’s not about simply banning NaHSO3. In many cases, no easy replacement keeps food fresh or prevents wine from turning. Instead, there’s value in using smarter dosing systems and ongoing workplace education, helping cut down on waste and accidents. Food makers keep an eye open for alternative natural preservatives, and researchers try to balance safety and effectiveness. It takes a mix of regulation, innovation, and hands-on caution to use chemicals like this wisely.

Understanding sodium hydrogen sulfite and its formula removes some of the mystery but also highlights the need for responsibility. Chemicals can help, but using them well means knowing the risks, learning from experience, and finding better methods wherever possible. Real progress usually happens in small, practical steps, guided by facts and a commitment to do a little better each time.

How should Sodium Hydrogen Sulfite be disposed of?

Looking Beyond the Label

Sodium hydrogen sulfite might sound like the kind of stuff that only matters in big industrial tanks. Anyone who has spent time in a chemistry lab or worked with photographic chemicals knows how easy it is to underestimate what a jug of this stuff can do in the wrong place. Pouring it down the drain doesn’t always feel risky until sewer fumes start coming back up or fish turn belly-up downriver. As someone who’s watched a science teacher scramble to deal with a clogged fume hood, it hits home that carelessness with disposal leaves more than a mess behind.

Environmental and Health Hazards

This chemical reacts pretty quickly with acids, giving off a sharp smell and pumping out sulfur dioxide gas. That’s not only rough on your lungs, it’s a hazard for anyone nearby with asthma. In the soil or water, it takes away oxygen – choking out aquatic life. Once it slips into city water treatment systems, it can throw off the balance, stripping out the oxygen that bacteria need to break down waste. It took a single afternoon in an environmental science class, tracing chemical spills in the city, to understand how easy it is to lose track of where a few ounces end up—and how long the damage sticks around.

Smart Steps for Disposal

The first step always starts with stopping and checking. Local hazardous waste guidelines usually come from real horror stories—cleanup crews dealing with illegal dumps, or sick workers trying to trace a smell in the pipes. Calling the local waste authority adds a layer of frustration, but pays off. Most cities run collection days for household and lab chemicals. Some schools or companies contract with hazardous waste haulers. The cost always beats emergency cleanup fees or a lawsuit when chemicals show up somewhere they shouldn’t.

Neutralization Is Key

Before even thinking about open drains or trash cans, neutralization makes the biggest difference. Sodium hydrogen sulfite reacts with simple bases like baking soda (sodium bicarbonate). With gloves, eye protection, and lots of ventilation, add the base in small amounts. Stir it until the fizzing stops and the mixture tests close to neutral using pH strips. That’s as close as it gets to safe for any future steps. Never mix with acids or bleach—nothing clears a room faster than a cloud of toxic gas or unexpected heat.

Small Batches, Less Trouble

Breaking the disposal into smaller containers keeps the risk, and the smell, under control. Sealed, labeled, and stored away from heat or sunlight, the leftover neutralized mix waits for hazardous waste pickup. There’s no shortcut that feels good the next morning if someone gets a whiff or pipes go weird. It only takes one headline about a school evacuated for people to ignore a simple set of rules to make future lab work a headache for everyone.

Ideas for Reducing Future Waste

For labs or small businesses, planning purchases helps. Every leftover bottle is a new headache next time. Sharing supplies, switching to less hazardous alternatives, and regular audits make sense. In schools, turning disposal into a teachable moment has more impact than another worksheet. The rules matter because, in the long run, skipping steps hurts more than it saves money or time. Responsible handling protects not just places, but people.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | sodium hydrogensulfite |

| Other names |

Sodium bisulfite Sodium acid sulfite |

| Pronunciation | /ˌsoʊdiəm haɪˈdrɒdʒən ˈsʌlfaɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium hydrogen sulfite |

| Other names |

Sodium bisulfite Sodium acid sulfite Monosodium sulfite |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm haɪˈdrɒdʒən ˈsʌlfaɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7631-90-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | Beilstein Reference: 3642761 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:37955 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1356 |

| ChemSpider | 14116 |

| DrugBank | DB09462 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.891 |

| EC Number | 231-548-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 778 |

| KEGG | C02335 |

| MeSH | D011225 |

| PubChem CID | 23666362 |

| RTECS number | VZ2000000 |

| UNII | 34R6PS43ND |

| UN number | UN2693 |

| CAS Number | 7631-90-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3568014 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:37958 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1356 |

| ChemSpider | 21709 |

| DrugBank | DB09462 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.860 |

| EC Number | 231-548-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 778 |

| KEGG | C00847 |

| MeSH | D012964 |

| PubChem CID | 23743238 |

| RTECS number | VZ2000000 |

| UNII | 6Q8U766M1S |

| UN number | UN2693 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | NaHSO3 |

| Molar mass | 104.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Sulfur dioxide odor |

| Density | 1.48 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -4.29 |

| Vapor pressure | < 1 mm Hg (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.97 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.83 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | `-40.5×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol` |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.334 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 1.79 D |

| Chemical formula | NaHSO3 |

| Molar mass | 104.06 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Pungent sulfur dioxide odor |

| Density | 1.48 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | soluble |

| log P | -4.27 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.81 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.81 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | −53.0·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.333 |

| Dipole moment | 1.70 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 91.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -547 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -104.6 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 92.9 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | −547.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -947.9 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V03AB02 |

| ATC code | A01AD11 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes severe skin burns and eye damage, may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS05, GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302, H318, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P261, P280, P301+P330+P331, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-1 |

| Autoignition temperature | 220°C (428°F) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 1420 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 1540 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WF6060000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL = 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 15 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 300 mg/m3 |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H314: Causes severe skin burns and eye damage. H335: May cause respiratory irritation. H302: Harmful if swallowed. H318: Causes serious eye damage. H317: May cause an allergic skin reaction. H412: Harmful to aquatic life with long lasting effects. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P271, P301+P312, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P330, P403+P233, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-1 |

| Autoignition temperature | 220°C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 1540 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 1310 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WS5600000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 100 mg/L |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 70 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sodium metabisulfite Sodium sulfite Sodium thiosulfate Potassium bisulfite Sulfurous acid |

| Related compounds |

Sodium metabisulfite Sodium sulfite Potassium bisulfite Sulfurous acid |