Sodium Glutamate: Past, Present, and Future of a Flavor Powerhouse

Historical Development

Many people know sodium glutamate by the brand name MSG. Its story starts in early twentieth-century Japan, when Kikunae Ikeda, a chemist seeking to unravel the umami taste in seaweed broth, identified and extracted glutamic acid as the source. He saw potential beyond his own kitchen table and commercialized it, paving the way for factory production under Ajinomoto, a company still in the game today. The demand surged as busy households and food producers clung to anything that boosted flavor without boosting cost. After World War II, factories across Asia and beyond churned out mountains of MSG, making it a staple in fast food, processed snacks, and restaurant kitchens. The West’s romance with sodium glutamate hit a hitch in the 1960s from unfounded health scares, yet global use pushed on, especially in regions where umami is a prized taste.

Product Overview

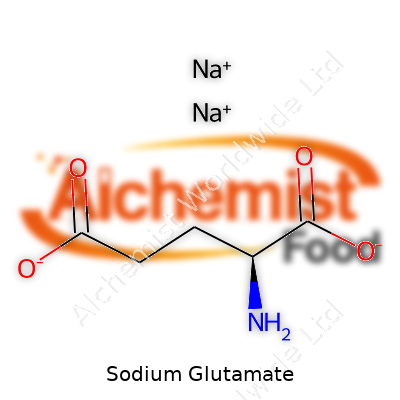

MSG stands for monosodium glutamate, the sodium salt of glutamic acid, one of the most common naturally occurring amino acids. Its job in food is to highlight savory flavors, adding depth to soups, snacks, sauces, and instant meals. The chemical formula is C5H8NO4Na. Usually, you find MSG as a fine white crystalline powder that dissolves easily in water. Simple in looks, but mighty in the way it can transform bland tastes into something crave-worthy.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Visually, sodium glutamate looks much like table salt: white, odorless, and free-flowing. Its melting point hovers just over 230°C, and it readily dissolves in water to form a clear solution with a strong umami character. In practical terms, its ionic structure lets it activate taste receptors on the tongue by matching perfectly with the cluster of glutamate receptors in human taste buds. Stable at room temperature, MSG neither breaks down nor reacts with common food ingredients during storage or regular cooking. From lab data, the pH of a moderate aqueous solution leans slightly toward alkaline, often between 6.7 and 7.2.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Quality standards vary by country, but food-grade MSG needs to meet purity minima of about 99%, with sodium chloride and other mineral impurities capped at fractions of a percent. Labels must list the product by its common name, but sometimes you’ll see E621 (its food additive code in Europe). In the US, regulations require a clear declaration on ingredient lists if a product contains MSG separately. Some companies call out “No Added MSG,” even if ingredients naturally rich in glutamates sneak in. The Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Health Organization both consider proper use of MSG as safe, and international labeling guidelines mostly echo this stance.

Preparation Method

Today’s MSG hardly ever comes from seaweed like in the old days. Most manufacturers work with fermentation—a bit like making beer or yogurt. Bacteria feed on carbohydrates sourced from crops such as sugarcane, beets, or corn, converting the sugars into glutamic acid. After fermentation, the liquid gets filtered, neutralized with sodium to form mono-sodium glutamate, then crystallized and dried. Processes follow strict sanitary protocols to avoid cross-contamination or off-flavors. Large-scale plants automate most steps, but quality checks, monitoring for bacterial contamination, and fine-tuning pH require a human touch. Residual microorganisms and heavy metals stay well below international regulatory limits.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

MSG sits at a crossroads between chemistry and biology. Heating it in normal cooking doesn’t produce new compounds that threaten health or taste. Exposing it to intense conditions like high heat in a dry skillet leads to breakdown and browning, turning it into pyroglutamic acid with a loss in flavor punch. MSG manufacturers sometimes adjust the fermentation process or change bacterial strains to increase yield. Chemists have tinkered with derivatives, looking for versions that dissolve faster or might interact differently with taste receptors, but plain MSG remains the most popular and best studied.

Synonyms & Product Names

MSG goes by a batch of names on commercial packaging and in ingredient lists. Look out for “monosodium glutamate,” “sodium glutamate,” or the European code “E621.” In some Asian markets, brands pitch MSG as “seasoning salt,” “umami seasoning,” or “flavor enhancer.” Shopping for food, you’ll find Ajinomoto and Vedan as brand titles known around the world. Some restaurants and processors label it simply as “flavor enhancer,” which can make it tricky to spot depending on your dietary preferences.

Safety & Operational Standards

Countless regulatory groups, from the US Food and Drug Administration to the European Food Safety Authority, consider MSG safe. Some people report mild headaches or flushing after large doses, known as “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” decades ago, but comprehensive research hasn't supported a direct toxic link at typical food levels. Factories need good hygiene, strong batch records, and regular inspections to keep product quality consistent. Occupational exposure happens mainly during bulk handling, with standard dust masks and gloves keeping it in check. Proper storage—sealed, dry, and out of direct sunlight—prevents caking and keeps the product effective.

Application Area

MSG stays busy in the food world. Every ramen seasoning packet, instant soup, canned stew, and flavored potato chip owes much of its punchy flavor to monosodium glutamate. Chefs mix it into spice blends, bouillon, and sauces to boost savory notes without overloading on salt. Fast-food outlets rely on it to produce consistent flavors batch to batch. Snack makers and restaurant kitchens in Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas all call on MSG to hold diners’ attention and set their dishes apart. It has also seen limited use in animal feeds, with indications that it could influence consumption and growth, but food uses far outpace any farm applications.

Research & Development

Researchers look at everything from optimal fermentation organisms to ways to create low-sodium or allergen-friendly blends. Some teams work with genetic engineering, creating bacterial strains that churn out glutamic acid more efficiently, which can bring down production costs and boost sustainability. There’s ongoing lab work toward discovering other amino acids and derivatives that mimic MSG without the same label stigma. Some food chemists look for ways to combine MSG with other savory-rich compounds—like yeast extract or nucleotide salts—for a more rounded flavor boost. Development teams have tried to encapsulate MSG in fat or starch to slow release in foods, eyeing better heat stability and reduced clumping on storage shelf.

Toxicity Research

Early scare stories suggested MSG might cause asthma or migraines, but broad clinical studies keep returning little to no danger for the general population eating normal amounts. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives placed MSG in the safest category, “ADI not specified,” meaning they see no risk at ordinary use levels. Some rodent studies at much higher doses showed potential neuroactive effects, but these results did not translate to humans. Care teams do recommend caution for people with rare metabolic disorders, such as those unable to process certain amino acids. Nutritional studies haven’t found any direct connection between MSG and obesity, diabetes, or cancer. That said, MSG is no superfood—it carries sodium, and overconsumption could push up blood pressure for salt-sensitive folks.

Future Prospects

The worldwide push for healthy, flavorful, and affordable food keeps sodium glutamate relevant. Consumers chase “clean labels” these days, so producers experiment with process tweaks or marketing tactics to sidestep negative perceptions. Researchers probe new fermentation sources, like agricultural waste, to make MSG greener and more cost-effective. Some companies try mixing MSG with potassium salt or novel plant proteins to cut sodium content and meet nutrition guidelines. Global markets, especially Asia and Africa, expect steady demand as rising urbanization and changing diets drive sales of instant and processed foods. Nutritional advances, like pairing MSG with fiber or plant protein for better mouthfeel, may soon land new products on shelves. MSG’s role may shift along with consumer trends, but its bold ability to lift the flavor of everyday meals keeps it in the spotlight across kitchens large and small.

What is sodium glutamate used for?

The Powerhouse Behind Flavor

Walk into any kitchen and start checking the seasoning shelf. There’s a good chance you’ll spot a white, crystalline powder labeled monosodium glutamate—MSG for short. Billed as a “flavor enhancer,” this ingredient has stirred quite a discussion in food circles for decades. The real reason it keeps showing up isn’t magic or food industry trickery. MSG delivers umami, that fifth taste people recognize yet find tough to describe. It’s the rich, savory note found in foods like tomatoes, mushrooms, parmesan, and soy sauce.

Everyday Cooking and World Cuisine

My grandmother never hesitated to add a pinch of MSG to her soups if the flavor fell dull; these meals brought everyone back for seconds. In most homes across East and Southeast Asia, a rice cooker and a jar of MSG share counter space with soy sauce and salt. Cooks working with tough cuts of meat, vegetables past their prime, or lower-fat broths turn to sodium glutamate to give dishes a lift. Research from the International Food Information Council shows MSG pops up the most in processed snacks, seasoning mixes, instant noodles, and frozen meals.

The Science That Backs the Taste

MSG taps into the way our taste buds detect glutamate, a naturally occurring amino acid. Human saliva even contains glutamate, and our mothers pass glutamate to us in breast milk. Decades of scientific analysis, including work published by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, have found MSG safe at typical consumption levels. The wild stories of “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” never translated into consistent real-world problems under controlled study.

Restaurants, Home Cooks, and Saving Money

Restaurants often rely on MSG to keep flavors strong while using basic ingredients. Instead of heavy amounts of cream or butter, a bit of sodium glutamate satisfies the craving for taste without blowing up calories or the budget. At home, I’ve rescued plenty of bland dishes—beans, vegetable stews, or even mashed potatoes—using just a dash. With food prices climbing, MSG stretches every grocery dollar by taking humdrum vegetables and leftovers to new heights.

Health, Misinformation, and Smart Choices

MSG runs into a wall of suspicion thanks to decades of rumor and outdated studies. Nutritionists now recognize that cutting out all sodium glutamate doesn’t offer any special health protection for most people. On the other hand, people with rare disorders like glutamate sensitivity should work with their healthcare providers. The bigger health challenge usually hides in the sodium content—MSG has less sodium than table salt but still needs respect if you’re watching your intake for blood pressure.

Smarter Seasoning for the Future

Food's not just fuel; it’s connection, comfort, and well-being. MSG lets cooks build big flavor without heavy salt or fat, opening doors for healthier habits. Community groups and nutrition educators have a job to do—help people see past old scare stories and understand real choices. Balancing flavor and health means working with the best information and skipping the shortcuts that sidestep both science and common sense.

Is sodium glutamate safe to consume?

What is Sodium Glutamate?

Sodium glutamate, often called MSG, pops up in all sorts of food. Walk down the aisle with instant noodles, frozen meals, or snacks—there it is, adding umami, that deep savory taste people crave. My own kitchen has a jar for boosting stir-fry flavors, the kind you find in any Asian market.

The Science Behind MSG’s Reputation

MSG gained a bad image in the late 1960s. Some folks reported headaches and other weird symptoms after eating Chinese food, and MSG ended up shouldering the blame. The term “Chinese restaurant syndrome” took off in media, creating suspicion about this common food additive. Yet, decades of research tell a different story.

Groups like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and World Health Organization have checked MSG’s effects over years and found no concrete link to health troubles in healthy people. A review from 2018 in the Journal of Clinical Nutrition showed that MSG’s so-called negative effects don’t turn up in well-controlled studies where people don’t know if they’re eating MSG or not. Symptoms like headaches often result more from expectation and suggestion than any actual response to the ingredient.

The FDA puts MSG in the “generally recognized as safe” group. Some people are sensitive and notice tingling or flushing if they gobble up piles of it in one go, but the average eater doesn’t encounter issues in normal amounts. In Japan, MSG’s birthplace, it’s used daily even in home-cooked soups. There’s no wave of hidden illness tied to it—just flavorful meals.

Fear and Food Choices

With food, much of the fear comes from the unknown. At family celebrations, I’ve heard relatives complain about MSG, diving for ingredient labels. They often miss that tomatoes, Parmesan cheese, and mushrooms all come loaded with natural glutamates, which the body can’t tell apart from the added kind. MSG isn’t some wild lab invention. It’s simply salt with extra glutamate, which already exists in many common foods.

One real thing to watch out for: MSG can be used in over-processed foods to trick the palate into thinking something tastes fresher or heartier than it actually is. If a meal needs MSG just to taste like food, maybe it’s time to cook more from scratch, using real stock and vegetables. The easiest way to avoid unwanted additives is to pay attention to whole, simple ingredients you trust.

Better Eating: Knowledge Over Fear

We live in a world where labels matter and choosing what goes into your body makes a big difference. The evidence so far points to this—MSG won’t hurt most people eating it as part of a balanced diet. I look at it the way I look at salt or sugar: a little improves food, too much drowns out every other flavor and might bring health concerns.

Listening to your body makes sense. If you eat something and feel off, cut back. Talk to your doctor if it happens more than once. For most, though, the science supports that enjoying that umami kick from time to time won’t spell trouble. The key comes down to moderation and understanding—not rumor or hype.

Looking Forward

As research moves on and people share more accurate information, conversations around MSG are starting to turn. Instead of labeling it an enemy, folks are realizing it’s just another tool in the kitchen. Balance, informed choices, and a little bit of skepticism towards food scares can help everyone cook and eat smarter. That’s good news for anyone craving a bowl of broth with that deep, satisfying note only glutamate brings.

Does sodium glutamate cause allergic reactions?

What is Sodium Glutamate?

Sodium glutamate, better known as monosodium glutamate or MSG, turns up in noodle soups, snack chips, canned vegetables, and restaurant stir-fry. Cooks sprinkle it for an extra punch of umami. The stuff’s been a food fixture since the early 1900s, yet folks keep calling it into question, with some blaming it for racing hearts, headaches, and allergic reactions after eating foods that contain it.

Experience with MSG Concerns

Cracking open a bag of chips as a teenager, I remember hearing my friends mutter, “That stuff gives me a headache.” Years later, I looked through medical journals and asked nutritionists whether anyone actually needs to fear MSG. The real story seems tangled between personal accounts and what the science actually shows.

The Science and Allergic Reactions

Medical researchers dug deep into MSG’s reputation. Rigorous double-blind trials, including those from the Food and Drug Administration and organizations like the World Health Organization, show no clear link between MSG and classic allergic reactions—such as hives, swelling, or anaphylaxis. The immune system seems to ignore MSG, unlike peanuts or shrimp, which set off a real allergic cascade in some bodies.

Some people talk about the “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”—flushed skin, headaches, or chest tightness after eating dishes with MSG. Researchers call this a food intolerance, not an allergy. The symptoms are usually mild and pass quickly. They happen when folks eat large amounts on an empty stomach. For most people, sipping a broth with MSG or munching on seasoned corn chips doesn’t bring on any troubles.

Breaking Down the Fear

Health authorities across Europe, North America, and Asia have spent years reviewing MSG. Each time, they come to the same point: for healthy adults, MSG isn’t dangerous at the amounts found in food. The FDA even labels it “generally recognized as safe.” If MSG posed real danger to the general population, countries with high daily MSG consumption—like Japan or South Korea—would have seen waves of allergic illness tied to their staples. That never happened.

Some parents talk about wanting to avoid MSG for kids. Scientific panels see no risks for children at normal levels either. The nervous system handles glutamate—the main part of MSG—in the same way, whether it comes from Parmesan cheese, tomatoes, or a seasoning packet. No food police force recommends banning it from children’s meals.

What to Do for Sensitive Eaters

Some folks say MSG upsets their stomach or leaves them feeling weird. In my case, eating a steaming bowl of ramen with extra MSG powder never gave me problems, but everyone’s got unique quirks. If you think you react, trust your body: skip it, read labels, or talk to your doctor. Food labels must list MSG when it’s an ingredient. If an ingredient makes somebody feel sick, there’s no shame in leaving it out, even if medical tests say it’s not an allergy.

Looking At Solutions

Education stands out as a better remedy than panic for ingredient worries. Anyone confused about MSG’s effects could ask their healthcare provider, especially if allergies or sensitivities run in the family. Chefs and grocery producers should keep offering clear ingredient lists, so anyone controlling what they eat has the tools they need. Most of the evidence points to MSG as a flavor booster, not a public health threat.

Familiar foods can sometimes stir up big debates, but with MSG, the science tells one story and urban legend tells another. Trusted sources and real-world experience can help clear things up, making the dinner table a less stressful place.

Is sodium glutamate the same as MSG?

Why the Names Cause So Much Stir

Food debates heat up fast, but few ingredients spark as much chatter as monosodium glutamate—better known as MSG. Walk into any grocery, search an ingredient label, and “sodium glutamate” might pop up beneath a list of unfamiliar chemicals. People wonder if this is the same stuff that restaurants tossed into fried rice back in the day, back when folks blamed MSG for itchy skin and headaches. The simple answer: sodium glutamate and MSG are the same thing. MSG stands for monosodium glutamate. It’s just one sodium atom attached to glutamic acid, a natural amino acid found in foods such as tomatoes, cheese, and mushrooms. That’s the truth behind the mysterious E621 on European labels—the food industry code for MSG.

The Flavor Kick You Already Love

I’ve cooked since high school, and nothing wakes up the flavors in a tired pot of soup like a pinch of MSG. In my family’s kitchen, we used a tiny amount to give sautéed greens or broth extra depth. MSG doesn’t cover up a dish; it helps round out flavors already there. Glutamate brings out that crave-able savory taste called “umami.” The same taste that makes Parmesan cheese or slow-cooked tomatoes stand out. It’s no different in form from the stuff your body breaks down when you eat meat or drink tomato juice.

Much of the fear around MSG started decades ago—partly from anecdotal reports and partly from myths that spread before researchers had a handle on food sensitivities. Responsible scientific reviews (including reports from the FDA, WHO, and the European Commission) have not found consistent evidence that MSG causes health issues for the majority of people. People talk about “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome,” but studies haven’t pinned widespread health reactions to the additive at the doses used in cooking or processed foods. Some do report rare sensitivities—so, as with anything, listen to your own body if you notice symptoms.

Health, Science, and Real-World Solutions

Many health professionals agree: moderating sodium matters far more than demonizing one ingredient. Most processed foods pack plenty of regular table salt (sodium chloride), and that’s what really pushes up the average person’s blood pressure. Using MSG can actually cut the total sodium in recipes, since it contains about one-third the sodium found in common salt. Swap out part of the salt for MSG and the savory notes stay strong with less saltiness. That’s handy advice for home cooks working toward heart-healthy goals.

As someone who reads supermarket labels, I understand parents and cooks worry about what goes into their meals. The scientific consensus around MSG gives room to focus on other dietary choices that truly impact health—fiber, added sugars, good fats. Nutrition is bigger than any one seasoning.

Lifting the Fog: Practical Steps

Anyone confused by long ingredient lists can call brands or look up reputable food safety organizations. I check answers with dietitians or national food agencies rather than random internet blogs. Teaching yourself to separate marketing spin from fact can help families feel good about what they eat. If you live with dietary restrictions, talk to your doctor or a registered dietitian for peace of mind.

The real takeaway here: sodium glutamate and MSG name the same compound. Most of the fears rest on shaky ground, while the facts continue to point to moderation and informed choices over fear. Embracing a realistic look at food science helps everyone eat better and worry less at the dinner table.

What foods contain sodium glutamate?

How Sodium Glutamate Gets Into Our Food

Sodium glutamate, often called monosodium glutamate or MSG, works as a flavor enhancer. It delivers that unmistakable savory or “umami” taste that people associate with ramen broth, snacks, and some processed foods. Once you’ve gotten used to the savory punch MSG gives to soups and chips, it’s not surprising to notice its presence throughout the grocery store aisles.

Common Foods with Added MSG

Canned soups and instant noodles almost always contain MSG. The boost it provides means manufacturers don’t have to rely as heavily on real meat or bones for richness. Potato chips, cheese-flavored crackers, ranch-flavored dressings, and flavored nuts include it for that satisfying aftertaste. Supermarket rotisserie chickens and fried chicken from fast food spots will often rely on MSG in the seasoning blend, amplifying the meaty flavors while smoothing out the salt.

It turns up in frozen entrees, especially those with gravy, stir-fry sauce, or noodles. Soy sauce, oyster sauce, and some brands of bouillon cube—especially the ones made abroad—include sodium glutamate to deepen the taste. Seasoned instant rice mixes and stuffing blends use it in their herb and spice powders, for a more full-bodied flavor profile.

Hidden Sources Beyond Obvious Labels

Even if you avoid products with “MSG” in the ingredients list, the story doesn’t end there. Sodium glutamate also hides behind names like “autolyzed yeast extract” or “hydrolyzed vegetable protein.” These ingredients act much like MSG by providing the same rich and satisfying taste foundation. Snack seasonings and meat-flavored ramen flavor packets usually rely on these hidden forms.

Many processed meat products—like hot dogs, sausages, and deli ham—add MSG or related glutamates. The boost to umami makes each bite taste meatier. Stores with bulk snack bins, especially those selling spicy or barbecue-flavored corn chips, sprinkle on seasoning mixes containing MSG or its relatives.

Natural Presence in Fresh Foods

Some people forget that glutamate, without the sodium, shows up naturally in plenty of real foods. Tomatoes, mushrooms, parmesan cheese, and anchovies pack a natural dose. Many Asian broths and fermented products owe their distinct taste to the natural glutamates inside kombu (kelp), miso, and soy sauce brewed the traditional way. Roasted nuts and aged cheeses, parmesan in particular, get their addictive flavor largely from glutamate.

Why It Matters: Taste, Health, and Transparency

For many folks, understanding which foods include sodium glutamate makes it possible to make more informed choices. Though research over the years has not shown a clear link between standard MSG consumption and health issues in the general population, people with sensitivities may feel headaches or nausea after eating foods loaded with MSG. Individuals with hypertension or those watching sodium intake will benefit from keeping an eye on labels due to the sodium content.

If you want to reduce your intake, cook from scratch more often. Rely on naturally umami-rich foods—like slow-roasted tomatoes, mushrooms, or seaweed—when deepening a dish’s flavor. Stay savvy about ingredient names on packaging. If in doubt, look past the marketing and scan the fine print, since MSG and its relatives sometimes appear under different aliases.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Sodium 2-aminopentanedioate |

| Other names |

Monosodium Glutamate MSG E621 Sodium 2-aminopentanedioate |

| Pronunciation | /ˌsəʊdiəm ˈɡluːtəmeɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | sodium 2-aminopentanedioate |

| Other names |

Monosodium Glutamate MSG E621 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsəʊdiəm ˈɡluːtəmeɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 142-47-2 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3Dmol.js?cid=23672387` |

| Beilstein Reference | 1906112 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:52519 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL140997 |

| ChemSpider | 22259 |

| DrugBank | DB03744 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 07e9d7c9-40d8-4fc3-80ed-ffb1b4317e55 |

| EC Number | 211-519-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | 5979 |

| KEGG | C00286 |

| MeSH | D018709 |

| PubChem CID | 23672308 |

| RTECS number | WN0810000 |

| UNII | YDDD84VX6H |

| UN number | UN1322 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID6020670 |

| CAS Number | 142-47-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1916783 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:5259 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1409 |

| ChemSpider | 87649 |

| DrugBank | DB00142 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 13be3e82-8007-4313-ad13-71b65c1bb5bc |

| EC Number | E 621 |

| Gmelin Reference | 6367 |

| KEGG | C16260 |

| MeSH | D014825 |

| PubChem CID | 23672308 |

| RTECS number | MN9100000 |

| UNII | W81N5U6R6U |

| UN number | UN1320 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DJ8E5QWV6H |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C5H8NNaO4 |

| Molar mass | 169.111 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.62 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -3.7 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.25 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.07 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -24.8×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.493 |

| Viscosity | 47 mPa.s |

| Dipole moment | 6.1 D |

| Chemical formula | C5H8NNaO4 |

| Molar mass | 169.111 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 1.62 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -3.3 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.25 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 7.75 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -24.2×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.4900 |

| Dipole moment | 7.2 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 116.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -907.6 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -390.5 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 146.4 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -828.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -389.1 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A15BA01 |

| ATC code | A16AA04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. Ingestion may cause headache, nausea, and weakness. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0- |

| Autoignition temperature | Autoignition temperature: 801 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 15,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 15.9 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | RR297 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 8000 mg/m3 |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 15,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 15,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WV0325000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | Up to 6 g/person/day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 800 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Monopotassium glutamate Monosodium aspartate Calcium glutamate Magnesium glutamate |

| Related compounds |

Monopotassium glutamate Glutamic acid Monosodium aspartate |