Saccharin: Unwrapping the Story, Science, and Future

Historical Development

Saccharin's journey began in 1879 in a Johns Hopkins University lab, by accident, when Constantin Fahlberg noticed his hands tasted sweet after a day’s work experimenting with coal tar derivatives. People latched on to this sweetener right away. It offered an alternative—especially for diabetics and anyone wanting to avoid sugar’s calories—long before aspartame or sucralose popped up. Through two world wars and sugar shortages, saccharin helped keep food sweet without draining supplies. In the early 1900s, regulatory debates about its safety pushed and pulled saccharin’s reputation. Official bans never really held, since strong demand from diabetics and soldiers kept pushing it back into people’s kitchens. The story reflects the real-life push-pull between science, regulation, and the public’s sweet tooth.

Product Overview

Saccharin arrives in grocery stores, labs, and industrial facilities mainly as a fine, white crystal that packs a punch—about 300 to 500 times sweeter than table sugar. You only need a tiny bit to sweeten a drink or a batch of cookies, and that economy explains part of its persistence. As a zero-calorie sweetener, it doesn’t trigger spikes in blood sugar, so for diabetics, it’s been a valuable option. In the food world, you’ll find it tucked in tabletop sweeteners, diet sodas, baked goods, toothpastes, and even some medicines. Manufacturers appreciate its stability under heat and acidic conditions. Some folks complain about its metallic aftertaste, but product developers often blend it with other sweeteners to balance things out.

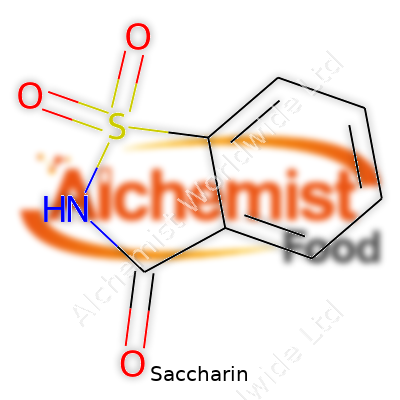

Physical and Chemical Properties

Saccharin, known chemically as o-benzosulfimide, presents itself as a white, odorless crystalline powder. It dissolves easily in water—especially in its sodium salt form—which explains why it mixes so well in sodas and diet drinks. Melting point hovers around 228°C. Saccharin stands up against heat and acidic conditions, a feature that few other alternative sweeteners can boast. Its sweetness can turn bitter when concentrated, so getting the ratio right matters for palatability. Most recall the slightly astringent or metallic taste if the balance tips.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Food-grade saccharin typically lands at about 99% purity or higher. Testing routines confirm the absence of hazardous byproducts, heavy metals, or residual solvents. The most common forms seen in foods are saccharin sodium and saccharin calcium, preferred for their solubility. Food laws in regions like the United States and Europe set maximum use levels, often between 80 and 300 milligrams per kilogram of food depending on the product. Food packaging must declare saccharin and its salt derivatives by their specific names and offer daily intake warnings based on local regulations. In the U.S., sweetener packets or beverages list “saccharin” with statements referring to its long-debated safety history, though nearly all official concerns have faded after several rounds of modern testing.

Preparation Method

Production once started with toluene as the raw material, running through sulfonation and oxidation steps, then cyclization to lock in the core benzosulfimide structure. More modern processes often begin with phthalic anhydride or methyl anthranilate—yielding less environmental impact and producing purer end products. Industrial setups handle the reactions in stainless steel reactors with precise control over temperature, pressure, and pH. After separation and purification, drying follows to deliver tightly specified quality metrics. The route matters for downstream purity, cost, and safety.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Saccharin’s unique benzosulfimide structure allows chemists to adjust its properties by reacting functional groups on the ring. Early methods left trace bitter-tasting byproducts, but cleaner syntheses virtually eliminated these. Chemists also created a series of salts—sodium and calcium saccharin most notably—that dissolve better and fit specific application needs in food, pharmaceuticals, and cosmetics. Some research aims at reducing the slight bitterness in pure saccharin through chemical tweaks. Its molecular backbone, however, remains largely unchanged because most modifications either ruin sweetness or complicate safety certification.

Synonyms & Product Names

Globally, saccharin appears under names like E954, Sweet ‘N Low, Sweet Twin, Necta Sweet, and in compounds as sodium saccharin and calcium saccharin. Laboratories and distributors might list o-benzosulfimide or benzoic sulfimide, especially in technical documentation. International labeling standards use these variations to clear up confusion, since buyers want to know exactly what they’re getting. On ingredient labels, reaching for “saccharin” or “sodium saccharin” gives consumers a clear signal.

Safety & Operational Standards

Food authorities around the globe keep a close watch on saccharin’s purity, permitted concentration, and residue levels in foods. Modern manufacturing lines use elaborate quality assurance programs, tracking batch purity with liquid chromatography, checking heavy metals, and verifying pH and solubility. Safe handling at the plant level involves gloves, goggles, and dust control. Approved daily intake stands at about 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight, based on global scientific consensus. Manufacturers face routine audits and must be ready to produce traceability data for every batch, since a slip in standards can lead to public distrust. Factory workers follow protocols for spill management, fire risk, and environmental containment, given the fine powder’s tendency to drift.

Application Area

Saccharin’s main job remains sweetening food and drinks where sugar either won’t do or isn’t welcome—think diet sodas, sugar-free gums, some pharmaceuticals, and a surprising range of toothpaste, mouthwash, and even livestock feeds. One standout application is table-top sweeteners, those pink packets found everywhere from diners to hospital kitchens. Pharmaceutical firms use it to mask bitterness in syrups and chewable tablets, making medicine more palatable for kids and adults alike. In personal care products, saccharin sweetens toothpaste and mouth rinses, helping encourage dental hygiene. Animal nutritionists find value too, since livestock sometimes eat better if feed tastes sweeter without wasted calories.

Research & Development

Decades of lab effort improved saccharin’s purity, stability, and safety. Early controversies over cancer links prompted significant animal testing, pushing for even tighter production controls and cleaner formulations. Researchers seek to lower the bitter notes through new blends or molecular tweaks. In food tech, combinations with aspartame or cyclamate create more sugar-like sweetness without off-flavors. Product developers also work on new dosage forms for both food and medicine, plus innovative delivery systems—think dissolving films or blended chewables. Modern genetic testing and food safety techniques check for any lingering risks, closing the gaps left by studies from the 1970s and 1980s.

Toxicity Research

For years, saccharin lived in the shadow of cancer warnings, after a 1977 study linked high doses with bladder tumors in lab rats. Subsequent reviews, including massive epidemiological studies, showed that humans metabolize saccharin differently and face no measurable increase in cancer risk at realistic intake levels. Regulatory bodies like the U.S. National Toxicology Program removed saccharin from their list of carcinogens in 2000, citing clear scientific evidence. Today’s research runs extensive tests on saccharin’s metabolic breakdown, tracking not only acute toxicity but potential long-term effects or rare allergic responses. Its safety record stands on mountains of controlled studies, consumer tracking, and ongoing batch-level analysis.

Future Prospects

Rising rates of diabetes and obesity keep demand for non-nutritive sweeteners strong, and saccharin’s resilience comes from decades at the front line. New sweeteners keep gaining ground, but saccharin’s reliability, heat resistance, and established safety profile give it continued relevance. Modern R&D focuses on blending—finding the least controversial and best-tasting combinations for calorie-free products. Regulatory hurdles will keep shaping its use, especially as food standards tighten around labeling and trace contaminants. Efforts to clean up feedstocks and further reduce environmental impact in manufacturing could help keep saccharin both competitive and socially responsible. With more global connectivity, food science networks share best practices faster than ever, helping saccharin stay relevant in an evolving marketplace.

What is saccharin used for?

What People Use Saccharin For

Saccharin ranks high among old-school artificial sweeteners. It brings that sweet kick without any sugar or calories. You find it in the pink packets on many diner tables, hidden in sugar-free gum, diet sodas, even some toothpaste. Most folks think of saccharin as the choice for coffee and tea, but food producers blend it into baked desserts, jams, salad dressings—even pharmaceuticals use its sweetening power to mask bitterness in liquid medicines or chewable pills. The low cost and long shelf life keep it a go-to for companies looking to trim calories while delivering a sweet taste.

Why Saccharin Sticks Around

Saccharin has a long shelf life. It does not break down quickly or spoil, making it attractive to manufacturers. It carries no calories, so people with diabetes or folks working on weight control often turn to it. For many people, the need to control blood sugar keeps them searching for sugar substitutes. Saccharin enables them to enjoy sweet flavors without serious health risks tied to added sugar.

Unlike some newer sweeteners, saccharin costs less to produce. I have seen it countless times as the "starter" artificial sweetener in restaurants and cafés unwilling to switch to costlier alternatives. I remember pouring those little pink packets into my grandmother’s coffee as a kid. Back then, sugar substitutes felt like a sign of progress, a way to enjoy the foods we like while dodging the downsides.

Concerns That Won’t Go Away

A few decades ago, controversy erupted as some early studies linked saccharin to cancer in lab rats. Regulators threw up warning labels, and folks got worried. Later, scientists realized those results came from using doses far above what anyone would ever eat. Huge studies, including reviews from the U.S. National Toxicology Program and the World Health Organization, showed saccharin does not cause cancer in humans. Still, some people avoid it, whether from old warnings or worries about artificial anything in their diet.

Some people notice saccharin leaves a metallic aftertaste. Food companies work around that by blending it with other sweeteners. This mix often delivers a sweeter taste that feels closer to real sugar, especially in flavored yogurt or fiber bars. Even with new sugar substitutes on the market—stevia, sucralose, monk fruit—saccharin stays in rotation because it brings predictable results at a low cost.

Looking For Smarter Sweetener Choices

Saccharin offers an option for those who need fewer calories or less sugar. For people with diabetes, this can open up foods they might otherwise avoid. That said, many folks rarely stop at a single sweetening agent anymore. Instead, we see more products combining artificial and natural sweeteners for better taste and mouthfeel, while working to keep calorie totals down.

The real trick for healthier eating still starts away from the sweeteners. I have found that choosing fresh fruits, whole foods, or drinking water is a better way to cut down on both added sugar and artificial ingredients. For anyone curious whether saccharin fits into their diet, doctors and registered dietitians help sort out risks versus benefits based on up-to-date evidence. If saccharin isn’t your taste, plenty of other sugar alternatives now line the shelves.

Moving Forward with Balanced Choices

Saccharin’s journey from lab experiment to supermarket shelf reminds us that food science keeps changing. Sweeteners like saccharin play a role in helping people reach health goals, but no one tool solves everything. I stick to moderation, enjoy a treat now and then, and trust that staying informed beats following old rumors or skipping sweets out of fear.

Is saccharin safe to consume?

Sweetener With a Past

People have turned to saccharin since the late 1800s. My first run-in with it came from my grandma’s white-lidded sugar bowl. She raved about saving calories and keeping her diabetes in check. Saccharin offers a sugar-like taste, doesn’t spike blood sugar, and doesn’t add calories. Diet soda, pink packets in diners, and low-calorie desserts still use it. Its long shelf life and cost outshine table sugar by a mile.

The Controversy and the Research

Curiosity about saccharin safety grew after 1970s studies on rats linked heavy doses to bladder cancer. Stores in my neighborhood carried warning labels back then. Since then, deep dives by the U.S. National Toxicology Program and the FDA show humans break saccharin down differently than rats. Large human studies, including those by the National Cancer Institute, haven’t tied saccharin to bladder cancer in people.

By 2000, health agencies removed saccharin from lists of proven human carcinogens. The American Diabetes Association accepts it as a sugar alternative. The FDA, World Health Organization, and European Food Safety Authority all set daily intake limits—a sweet spot that remains far below the amounts ever linked to health scares. For an average adult, this tops at about nine to twelve sweetener packets a day.

Modern Habits and Hidden Risks

Food and drink labels can leave folks guessing about which sweeteners end up in their snacks. People don’t always think to add up those little pink packets with the dozens of hidden sources. Folks who eat saccharin on top of other artificial sweeteners may overlook total exposure. Kids, who grab what’s in the fridge or pantry without thinking twice, get a higher dose for their body size than adults.

In my work with people trying to lose weight or manage diabetes, most want to understand how sweeteners affect energy and cravings. Artificial sweeteners like saccharin may not spark hunger, but cravings often sneak up on people anyway. It’s not just about what goes into your coffee. Taste patterns shape what ends up on plates and snack trays all day long.

What Matters Most: The Whole Diet

Most health experts I trust say moderation works best. Swapping every bit of sugar with saccharin won’t fix every health issue. Research around gut health and appetite keeps evolving. The gut microbiome, those trillions of tiny bacteria living in us, may react to artificial sweeteners in ways scientists don’t fully grasp yet.

Reading the small print on ingredient lists helps manage total intake. I’ve seen folks do well when they focus on whole foods—vegetables, fruit, nuts—and use sweeteners, natural or artificial, as flavor boosts, not meal mainstays. Simple steps like cooking more at home and choosing water over soda can shrink sweetener use without sacrifice.

Navigating Choices

Ask questions at your next doctor’s visit or with a dietitian if you’re unsure. For people with rare sulfa allergies, saccharin might cause hives or headaches. For most healthy people, current science shows saccharin as safe within reasonable limits, and that’s good news for folks still clutching their favorite sweet packets in their morning coffee.

Big answers in nutrition rarely come from a single ingredient. Saccharin’s story reminds us that simple swaps work best in the context of balanced eating, not as magic fixes. Respect for new research and honest label reading steer us in a healthier direction.

Does saccharin have any side effects?

People's Questions About Saccharin Safety Never Seem to Go Away

Saccharin has landed in millions of sugar bowls since the late 1800s. My grandma kept a little pink packet in her purse and added it to coffee at every family diner stop. She always said it tasted close enough to sugar, and at zero calories, it seemed like a small miracle. Decades later, saccharin continues to raise concerns about what it actually does inside the body. Plenty of folks have doubts: Does saccharin really cause cancer? Is it safe for kids or pregnant women? What about folks with gut problems?

What Science Has Found

Back in the 1970s, animal studies triggered a panic about saccharin causing bladder cancer in rats. Research grabbed headlines and led to warning labels that scared plenty of people off anything labeled “artificial.” But here's the crucial part: studies in humans never found that link. The National Cancer Institute, the Food and Drug Administration, and the World Health Organization all looked at the research and shifted their stance. FDA scientists eventually removed those alarming labels after finding no evidence tying normal saccharin use to cancer risk for people.

The occasional side effect that still shows up most often seems pretty boring by comparison: some people complain about headaches or a strange aftertaste. Rarely, folks with very specific allergies report rashes or swelling. Parents might want to be careful since research hasn’t nailed down every possible effect for kids, but most pediatric health groups say saccharin is safe in common food amounts.

Saccharin and Blood Sugar: Real Effects for People with Diabetes?

Living with diabetes means scanning any sweetener label with suspicion. Saccharin never raises blood sugar, so it’s technically a safe choice. Some studies suggest using lots of artificial sweeteners could affect the body’s sense of sweetness and appetite cues over time, but nothing links saccharin to blood sugar spikes. If you have diabetes, talking with a doctor helps tailor a plan if you’re worried about cravings or managing your sweet tooth.

The Gut Microbiome Question

Lately, research keeps returning to the gut microbiome. Some lab experiments show that big doses of sweeteners—including saccharin—can shift the mix of bacteria in the intestines. The science isn’t settled, especially for people using saccharin in realistic amounts. For now, dietitians tell clients not to dwell on a few packets of saccharin and to stick to a balanced diet full of fiber, fruits, and fermented foods known to really support gut health.

Safer Choices and Honest Trade-Offs

The wider question looms over all this: Do artificial sweeteners promise more than they deliver? Plenty of people wind up eating more processed snacks just because the label says “sugar-free” or “diet.” No single packet makes or breaks a healthy lifestyle, but small decisions add up. Anyone feeling nervous about artificial sweeteners can reach for other options like monk fruit, stevia, or just plain fruit when looking for sweetness.

Doctors, nutritionists, and public health groups usually agree on one thing: keep an eye on added sweeteners, whether natural or artificial, and don’t stress about the occasional taste. Saccharin isn’t a health villain, but neither does it fix the bigger issues around diet, processed food, or overall wellness. Balancing convenience, taste, and actual health still looks like the toughest puzzle in every household kitchen.

Is saccharin suitable for diabetics?

Saccharin and Blood Sugar: What Studies Show

Saccharin has been around for more than a century. This artificial sweetener drew interest as soon as people realized it doesn’t raise blood sugar. For diabetics, this detail matters. Diet often means watching sugar grams with an eagle eye. Saccharin’s structure passes straight through the body without breaking down, so it skips the blood sugar spike entirely. That’s a major selling point for anyone trying to stabilize their glucose. The FDA and the American Diabetes Association both list saccharin as a sweetener option for people with diabetes, and for good reason: randomized clinical trials such as a 2017 study published in Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology found no evidence that saccharin triggers insulin responses or pushes blood sugar out of safe territory.

Concerns About Saccharin and Health

Safety questions keep cropping up. Stories about saccharin and cancer stuck in people’s memories after rodent studies from the 1970s. Mice and rats developed bladder tumors when given exceedingly high doses (far more than any human would ever eat). Later research found that human bodies don’t react to saccharin in the same way. The National Cancer Institute and World Health Organization both state there’s no clear link between saccharin and cancer in people. Epidemiological studies haven’t found spikes in bladder cancer among saccharin users. Government agencies lifted warning labels decades ago.

There’s still debate about how artificial sweeteners might change gut bacteria. Some animal studies raised a flag, but large-scale studies in people haven’t settled that question. Research from Israel’s Weizmann Institute described shifts in some gut bacteria after regular heavy saccharin use, but the amounts used were much higher than most people consume. Ongoing research may bring more clarity, though right now, evidence of harm in real-world doses looks thin.

Day-to-Day Reality: Saccharin in Food and Drinks

Saying goodbye to sugar isn’t easy. In my own family, diabetes runs deep, and nearly everyone swaps out sugar for alternatives. Saccharin pops up in tabletop packets, canned drinks and low-calorie desserts. One thing we learned: even though saccharin offers a sweet taste without calories or glucose spikes, it leaves a lingering, slightly metallic aftertaste if too much gets used. That means variety helps. Blending a bit of saccharin with other sweeteners often gets closer to sugar’s flavor, while keeping diets on the rails. People who feel frustrated by the sugar restrictions have told me they’re grateful for these options, though they rarely rely on just one sweetener every day.

Smart Choices and Limits

No sweetener replaces healthy habits. A daily diet overflowing with artificially sweetened sodas and ultra-processed foods won’t boost well-being, no matter how blood sugar behaves. Nutrient-dense meals, full of veggies, lean protein and whole grains, set the foundation for good energy and health. Saccharin fits best as a tool for occasional indulgence, not a crutch for every meal or snack. The FDA sets a limit for safe intake—up to 15 mg per kilogram of body weight each day—a figure most people never approach.

Doctors, dietitians and diabetes educators remind us to keep perspective. If saccharin makes life a bit sweeter and makes diabetes management feel less punishing, it has a place at the table. People should always talk to their health team about what works for their own bodies, especially because taste and tolerance vary person to person. After trying different options, many folks find saccharin fits somewhere in the toolbox, helping them stick with a careful, balanced life.

How does saccharin compare to other artificial sweeteners?

A Small Pink Packet and a Mountain of Questions

Every diner table seems to have that little pink packet—saccharin. This sweetener has been around since a Johns Hopkins chemist discovered it in 1879. My own earliest memory of saccharin was my grandmother spooning it into her morning coffee, swearing that it kept her diabetes in check without losing the taste she craved. Nowadays, the options for sugar substitutes have multiplied. Choices include aspartame (blue packet), sucralose (yellow), and even plant-based stevia or monk fruit. With all these sweeteners, it’s natural to wonder: is saccharin still a smart pick?

Breaking Down the Choices

Saccharin carries a bold sweetness—about 300 to 400 times sweeter than table sugar. That means a sprinkle goes a long way. It doesn’t give calories, and it passes straight through the digestive tract. Aspartame delivers less sweetness per gram and gets digested, so folks with phenylketonuria need to avoid it. Sucralose, the main ingredient in Splenda, also packs a strong punch and resists breaking down when heated, making it simple for baking. Stevia sports a “natural” label since it comes from a plant, but extraction methods involve plenty of chemistry before it ends up on the shelf.

The Bitterness Factor

People complain about saccharin’s aftertaste. If you’ve ever tried it in plain tea, that bitter metal-like note is tough to miss. Sucralose and stevia can have aftertaste issues too, but food companies blend them with bulking agents to help mask weird flavors. For a long stretch, manufacturers mixed saccharin with cyclamate to improve flavor, though cyclamate ended up banned over cancer concerns.

Debates Over Safety

Back in the 1970s, headlines linked saccharin to bladder cancer in lab rats. My parents, along with half the country, stopped using it nearly overnight. Later research never found proof that humans face the same risk, and by 2000 the U.S. government agreed—removing warnings and easing the fear. Aspartame and sucralose also spend time under the microscope. Some studies raise eyebrows about everything from gut bacteria to headaches, though regulatory agencies like the FDA and European Food Safety Authority greenlight use within set daily limits. With stevia, the evidence runs short, mostly because it’s a newer kid on the block.

Public Health Perspective

The world faces soaring rates of obesity and diabetes. The hunt for zero-calorie sweetness matters. Science tells us that switching from sugar to any artificial sweetener can help cut calories, though there’s still an open question about long-term benefits or side effects. One 2023 review found artificial sweeteners may only shave off a tiny bit of body weight, and that their taste might stoke sugar cravings anyway. That lines up with my own attempts to diet—artificially sweetened sodas cancel the guilt, but I find myself hunting for hidden sugar elsewhere.

Finding the Right Balance

For most people, swapping sugar with any low-calorie sweetener likely poses little risk. Diabetics often benefit the most, keeping blood sugar stable, but the story isn’t as simple outside this group. Parents worry, yet pediatric dietitians now tell families that a small amount here and there isn’t dangerous. Still, no artificial sweetener stands out as magic. Taste, tolerance, and a bit of trial and error shape the best choices. The big lesson I’ve learned—don’t rely on one food fix to solve a much larger health issue.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 1,1-Dioxo-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one |

| Other names |

O-sulfobenzimide benzosulfimide saccharin sodium E954 ortho-sulfamoylbenzoic imide |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsæk.ə.rɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 1,1-Dioxo-1,2-benzothiazol-3-one |

| Other names |

Sodium saccharin Benzoic sulfinide E954 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsæk.ə.rɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 81-07-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 320436 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:18320 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1137 |

| ChemSpider | 5797 |

| DrugBank | DB00896 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03f7f91f-4dd8-40bb-98b0-1f83c3b5f145 |

| EC Number | E954 |

| Gmelin Reference | 8112 |

| KEGG | C01737 |

| MeSH | D013158 |

| PubChem CID | 5143 |

| RTECS number | WS0925000 |

| UNII | F6YK4MQR8V |

| UN number | UN1871 |

| CAS Number | 81-07-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1209632 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28201 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1409 |

| ChemSpider | 21101417 |

| DrugBank | DB00823 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.026.057 |

| EC Number | E954 |

| Gmelin Reference | 85240 |

| KEGG | C02445 |

| MeSH | D013174 |

| PubChem CID | 5143 |

| RTECS number | WS0925000 |

| UNII | F6YK7RS206 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C7H5NO3S |

| Molar mass | 183.18 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.83 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | 1.12 |

| Vapor pressure | 1.33E-07 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 1.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.58 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -39.5·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.587 |

| Dipole moment | 3.61 D |

| Chemical formula | C7H5NO3S |

| Molar mass | 183.18 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.83 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | sparingly soluble |

| log P | 1.34 |

| Vapor pressure | < 0.1 mm Hg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 1.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.58 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -52.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.347 |

| Viscosity | Low viscosity |

| Dipole moment | 3.47 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 276.6 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -414.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3982 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 289.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -413.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3960 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A10BX02 |

| ATC code | A10BX01 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0-✕ |

| Flash point | > 250 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 550 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): 17,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 17,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WN6500000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/kg bw |

| Main hazards | May cause irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory tract |

| GHS labelling | GHS07,Warning, H317 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 1, Flammability: 1, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Autoignition temperature | 550 °C (1022 °F; 823 K) |

| Explosive limits | Lower: 80 g/m³, Upper: 2300 g/m³ |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): 17,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 5000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WN6500000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) of Saccharin: 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/kg bw |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Dulcin Sodium cyclamate Acesulfame potassium Sucralose Aspartame Neotame Steviol glycoside |

| Related compounds |

Aspartame Acesulfame potassium Cyclamate Sucralose Neotame |