Saccharin Calcium: A Journey Through Science, Safety, and Solutions

Historical Development

Most conversations about sweeteners go back to table sugar, but the story of saccharin calcium starts in the late 1800s, during one of those serendipitous moments that often pluck new discoveries straight out of the chaos of research labs. Constantin Fahlberg, a chemist at Johns Hopkins, first noticed the sweet aftertaste of this substance—right on his own hands after a long evening’s work. At the time, diets heavily depended on sugar, both for pleasure and calories. People began searching for replacements not long after this discovery, especially with world wars and rationing putting sugar in short supply. Saccharin soon appeared in various products, but concerns about sodium intake among some groups and the drive for alternatives brought saccharin calcium to the scene. This compound offered a way out for those looking to limit sodium without giving up on artificial sweetness. The search for new sweeteners still reflects the original quest for balance and health.

Product Overview

If you pour a packet of tabletop sweetener labeled “saccharin," you might spot calcium saccharin among the ingredients. It’s known mainly for its role as a non-nutritive sweetener, meaning people use it for taste instead of nutrition. This form appears in tablets, powder blends, and liquid concentrates, ready for food, beverages, pharmaceuticals, and beyond. Manufacturers rely on its stability and long shelf life, particularly where heat or acidity would spoil other sweeteners. Few artificial ingredients can stand in a warehouse for years without noticing any change in quality. Saccharin calcium’s taste tends to linger, with a sweetening power hundreds of times greater than sugar—so only tiny amounts go into any given product.

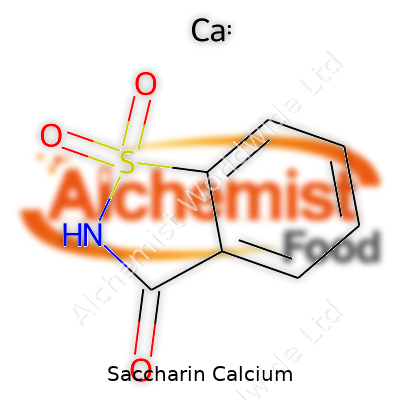

Physical & Chemical Properties

This compound comes in the form of a white, odorless crystalline powder that dissolves in water without much fuss. The taste, intensely sweet, sits somewhere between sugar and metallic, depending on whether the blend hides the aftertaste. The molecular structure resembles other sulfonamide derivatives, but the calcium salt makes it less soluble in some solvents compared to its sodium cousin. This matters for product developers who want fast or slow dissolution—there’s a reason beverage manufacturers choose carefully between salt forms. You can’t ignore the melting point or the tendency of the powder to clump in humid conditions, especially in tropical storage environments. Every property has a practical upshot in shipping and shelf stability.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers must stick to clear labeling under food law, especially in the United States and European Union. You’ll see purity requirements laid out by pharmacopeias and food agencies, without room for shortcutting. Limits on heavy metals and other impurities appear in every spec sheet because saccharin calcium can carry residues from processing if made carelessly. Regulatory bodies specify the minimum percentage of pure compound required and test for contaminants such as lead, arsenic, and moisture content by standard analytical chemistry methods. Labels must state the actual content, batch number, and often country of origin. There’s no room for ambiguity here—companies risk massive recalls or lawsuits if accuracy slips.

Preparation Method

Chemists start with o-sulfamoylbenzoic acid and pass through several steps to synthesize saccharin. The calcium salt forms by reacting the free acid with calcium hydroxide or calcium carbonate. Industrial setups may use reactors built for high-purity yields, with extra steps for filtration and drying. Each batch depends on maintaining tight pH control and temperature—too much variation, and purity tanks. The choice between batch and continuous processes reflects both the intended scale and local regulations. Systems require thorough cleaning protocols, as residues from previous runs can compromise the next batch’s quality and safety. These details matter most once you realize a misstep can lead to a tainted product shelf-wide.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Beyond the basic reaction with calcium compounds, researchers sometimes tweak conditions to develop purer or more functionalized versions. Hydrogenation, crystallization with different solvent systems, or complexing with other minerals can fine-tune the product for specific uses. In the lab, chemists have also explored substitutes for the sulfonamide group, creating analogues with marginally altered taste profiles or improved solubility. Every version faces the same rigorous scrutiny for safety, taste, and stability; small chemical shifts often ripple out to affect toxicity or how long the sweetener holds up in food storage. Those who develop new variants must stay ahead of both regulators and consumer expectations.

Synonyms & Product Names

Saccharin calcium appears under several trade names and synonyms around the world. Depending on the market or the manufacturer, it shows up as calcium saccharinate, E954(ii), or as branded blends mixed with carriers or stabilizers. The core chemical formula never changes, but labeling laws demand these alternative names. For food technologists, picking the right name is more about regulatory acceptance and consumer recognition than about chemistry. Packaging often lists both the chemical and marketing names, so customers wondering about “calcium saccharin” or “calcium saccharinate” can trace it back to familiar territory.

Safety & Operational Standards

Ten years ago, few conversations about artificial sweeteners would escape debate about cancer risk. Saccharin—both sodium and calcium—ran into these headwinds after rodent studies sparked fear about bladder cancer links. Agencies such as the FDA and European Food Safety Authority reviewed the data thoroughly, and new research cleared saccharin from the list of possible human carcinogens. Saccharin calcium remains GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) within recommended limits. In practice, food companies keep usage well below the Acceptable Daily Intake to sidestep even hypothetical risks. Plant safety standards focus on cleanliness, ventilation, and personal protective equipment for workers. Dust from the crystalline powder can irritate the respiratory tract—a minor point, but easy to manage using modern ventilation controls and worker education. Companies follow HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) plans to prove their sites meet both legal and ethical expectations for safe food production.

Application Area

Saccharin calcium travels far from the original sweetener packet market. Food and beverage companies use it wherever sugar brings either too many calories or stability issues. Think sugar-free gums, diet sodas, baked goods for diabetics, and even some canned fruits in regions where shelf life trumps everything else. Tablets for diabetics often include saccharin calcium thanks to its easy compression and dissolution in water—an underrated advantage for elderly or pediatric care. Pharmaceutical products sometimes contain it to mask bitter flavors in syrups or chewable tablets. Pet food uses have crept up, mostly to cover up off-putting flavors in veterinary medicines. Its lack of sodium makes it more appealing in hypertension diets, filling a niche that saccharin sodium cannot.

Research & Development

Current R&D in artificial sweeteners focuses on making blends that reduce the aftertaste while keeping sweetness high and calorie count zero. Saccharin calcium often gets paired with other sweeteners such as aspartame, cyclamate, or stevia, producing a more sugar-like taste. Food scientists continue to look for ways to cut the metallic tinge by adding masking agents. Some researchers test encapsulation techniques so the sweetener releases more slowly and tastes smoother. The newer focus on clean labels has pushed teams to investigate plant-based carriers and naturally derived process aids. Innovations in crystalline form and particle size also help manufacturers solve mixing and solubility challenges on high-speed production lines.

Toxicity Research

People’s worries about artificial sweeteners determined much of saccharin calcium’s path through history. Early toxicity tests flagged some risks, but new generations of studies have focused on realistic consumption levels—the doses people actually encounter in their food. Regulatory authorities around the globe, from the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives to the FDA, have set strict maximum intake levels based on decades of animal and clinical research. These limits provide big safety cushions even for heavy users. Still, researchers continue animal studies to catch long-term or subtle effects. Genetic toxicity and reproductive health are two hot spots, reflecting rising consumer demand for transparency about what’s in daily food. Surveillance never really ends, as new findings may prompt updates to recommended intake guidelines.

Future Prospects

Sugar consumption continues to decline in many developed countries, and the push for healthier alternatives shows no sign of slowing. Saccharin calcium, with its low cost and long shelf life, will likely stay important wherever affordability and accessibility matter. At the same time, consumer demand for “clean” or “natural” ingredients has rattled the market. Saccharin calcium remains synthetic, so shifting perceptions could slow its growth in premium grocery categories or brands that market purity as a selling point. Companies who use this ingredient will need to communicate not just regulatory compliance but health benefits and production transparency. Continued research into taste-masking and new delivery forms will likely keep the sweetener on the menu for beverages, medicine, and specialty foods for several years. The bigger challenge remains public trust. Industry, regulators, and scientists need to keep the lines open, explaining the evidence and responding clearly to consumer questions, if artificial sweeteners like saccharin calcium are to keep their place at the table.

What is Saccharin Calcium used for?

Where Saccharin Calcium Shows Up

Saccharin calcium pops up in places many don’t expect. It’s a non-sugar sweetener, chosen in products wanting to keep calories down. People watching their blood sugar see it in their morning coffee, their zero-sugar soda, or the chewable vitamins they hand to their kids. It’s not just a trick for taste buds; it helps manufacturers keep promises made to diabetics and calorie-counters.

Why People Choose Saccharin Calcium

Not everyone reaches for sugar’s crystal grains. There’s a real drive to trim sugar without losing sweetness. Saccharin calcium steps up when someone needs their favorite treats to come guilt-free. It’s sweet—about 300 times sweeter than table sugar. That means you barely need any to get the job done.

In hospitals and clinics, patients with strict diets need a sweet option that doesn’t mess up their routine. Parents who want their children to avoid tooth decay hand over sugarless gum. For years, I’ve watched folks reach for diet sodas at backyard barbecues and trust the “sugar-free” label on their favorite cough drops. Those seemingly small swaps add up over time for both personal health and public health.

Safety Under the Microscope

There’s old debate about artificial sweeteners, but science stands behind saccharin calcium when used responsibly. Studies run by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and health agencies in countries like Canada and across Europe reviewed stacks of research. The consensus: saccharin calcium is safe at levels you’ll find in food and drinks.

For people living with diabetes, this has opened the door to more food choices. Instead of feeling boxed in, they can eat and drink with less worry. Still, moderation matters—just like with anything. Some folks notice a bitter aftertaste or digestive upset if they use it too much. That’s a sign to listen to your body’s feedback.

Beyond Food: Other Uses

I’ve seen saccharin calcium sneak into places beyond the grocery aisle. Pharmaceutical companies use it to mask the flavor of medicines. That cherry-flavored syrup or chewable allergy tablet? Odds are, it gets its kick from saccharin calcium. With toothpaste and mouthwash, sweetening agents help folks stick with daily routines that keep mouths healthy.

In the lab, researchers use saccharin calcium to analyze water purity. It acts as a tracing agent because of its solubility and strong taste—even at tiny concentrations. It proves itself useful in places that have little to do with a sugar craving.

Challenges and Smarter Choices

One issue keeps coming up: trust. People worry about artificial ingredients because of stories from decades ago about cancer scares tied to laboratory rats. Regulators took notice. Later research found that those risks didn’t apply to humans eating or drinking normal amounts. Still, the confusion sticks around.

Parents and teachers have to answer tough questions from kids about what goes into snacks and drinks. Saccharin calcium, like all ingredients, deserves an honest look. People get the most from it with a balanced diet that favors whole fruits and vegetables and reads the fine print on packages.

All in all, saccharin calcium provides a tool. It can keep calories low, support dental health, and bring peace of mind to diabetics and calorie-watchers. In the end, it gives choice to people navigating a food landscape shaped by both tradition and science.

Is Saccharin Calcium safe for diabetics?

The Reality Behind Artificial Sweeteners

A lot of us want to cut down on sugar, especially after a blood sugar scare or a family member gets diagnosed with diabetes. The idea behind using artificial sweeteners like saccharin calcium sounds pretty straightforward: keep the sweet taste, skip the sugar spike. For folks with diabetes, every gram of sugar can turn into a math equation. So turning to something like saccharin calcium, which brings sweetness without raising blood sugar, feels like a safe workaround.

Backing from Science

Saccharin calcium has been around for a long time. Way back in the 1970s, studies brought up cancer risks, but newer, higher-quality research has cast a much softer light on that old concern. Today, food safety organizations—including the U.S. FDA, European Food Safety Authority, and World Health Organization—give saccharin calcium the green light for human consumption, including for folks with diabetes. They reviewed all those cancer fears and found no evidence strong enough to warrant concern at typical intake levels.

Busting Blood Sugar Myths

The real draw for diabetics comes from saccharin calcium's sweetening action. This substance doesn’t break down into glucose in the body. So, eating something with it doesn’t raise blood sugar levels. Studies confirm that it travels through the body and gets excreted almost unchanged, not causing those blood sugar spikes you get from table sugar or corn syrup. For a person trading off dessert or drinks for better glucose control, this makes life a bit less complicated.

Digestion, Tolerance, and Taste

Saccharin calcium dissolves well and works in baked goods, drinks, and even packets for coffee or tea. Most people tolerate it without trouble; stomach upsets are rare at typical doses. Rare allergic reactions have been seen with saccharin in some people with sulfa allergies, but these remain outliers. For folks used to the taste of sugar, saccharin’s flavor may seem metallic or a bit off. Plenty of people get used to it – for others, blending with another sweetener helps smooth out the taste.

Is It the Only Answer?

Switching to sugar substitutes gives diabetics more control, but the long game isn’t only about avoiding sugar. It’s about building a better food routine, getting exercise, focusing on whole foods, and making sure any substitute doesn’t become an excuse to eat more sweets. The American Diabetes Association says non-nutritive sweeteners like saccharin can help reduce calorie and sugar intake if they don’t crowd out other healthy habits.

Looking at the Big Picture

Choosing a sweetener often comes down to personal preference, dietary goals, and trust in food safety boards. Saccharin calcium fits into modern diabetes care because it doesn’t push up blood sugar. People still need to stay mindful about how much sweetness they add to their diet in any form, since taste buds often crave more after long use. For someone worried about artificial ingredients, natural sweeteners like stevia might feel more comfortable.

Better Choices for Better Health

Getting good information and talking with a registered dietitian can make the process less overwhelming. Diabetics need to look at the bigger pattern of what goes on their plate. Saccharin calcium makes low-sugar living easier, but the healthiest path always brings in fresh veggies, lean proteins, enough fiber, and regular talks with a healthcare team. That approach grounds every decision—sweeteners included—in facts and real-life results.

Does Saccharin Calcium have any side effects?

Understanding Where Saccharin Calcium Lands in Our Food

Saccharin calcium steps in when people hunt for a sugar substitute that keeps calories low. With diabetes, obesity, and sugar-related health problems on the rise, folks often ask if these artificial sweeteners bring baggage. Some people might pop a pink packet in their coffee every day without thinking twice. The question sticks though—what’s the tradeoff?

Personal Experience and What Research Says

If you drink diet soda or chew sugar-free gum, you’ve probably had saccharin calcium. I grew up watching my grandmother pour sweetener into her tea, believing it kept her diabetes in check. She never complained about it, but now and then, she’d complain about a funny aftertaste—that deeply metallic tang isn’t for everyone. My own time with saccharin-sweetened drinks didn’t last long for that same reason.

Taste issues aside, some researchers point toward potential problems. Decades ago, saccharin faced backlash because of links with bladder cancer in lab rats. That set off alarms. The U.S. National Toxicology Program and World Health Organization later reported that those results didn’t line up for humans in the same way. The amount of saccharin people usually eat won’t line up with lab-rat doses. By 2000, saccharin stepped off the U.S. government’s list of possible cancer-causing substances—still, rumors keep spinning.

What Kind of Side Effects Matter for Real People?

Stomach troubles top the list for some people. Digestive systems don’t always treat sweeteners kindly—gas, bloating, or mild laxative effects show up sometimes. People sensitive to sulfonamides (the class of chemicals saccharin belongs to) can get allergic reactions. Symptoms like rashes, itchiness, or even swelling, though rare, demand attention. It’s not common, but if an allergy exists, it pays to listen to your body instead of brushing off strange signals.

Research often circles back to another roadblock: changes in gut bacteria. If you eat a lot of artificial sweeteners—including saccharin—some studies suggest your gut microbiome could shift in ways that don’t help glucose tolerance. While that research isn’t cut and dried, the gut works like a canary in the coal mine. Tossing in too many chemicals your body didn’t evolve with might not do you any favors over time.

Levels of Safety and Practical Considerations

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration labels saccharin calcium as “generally recognized as safe,” or GRAS. Most people can use it daily without consequences, so long as intake doesn’t skyrocket past the recommended daily intake. For adults, that means about 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day—pretty generous. Kids and pregnant women stand on shakier ground, so doctors usually steer them toward caution.

In my own life, reading labels has become less of a chore and more of a habit. Knowing what goes into my food arms me with the choice to pick what sits right. I tend to tell people: if you’re swapping sugar for health reasons, know what you’re taking in. Not everyone feels the impact the same way. Sometimes, less really means more, especially with artificial sweeteners.

What Helps People Make Informed Choices?

Doctors and dietitians suggest listening to your body, starting small with any new sweetener. If something feels off, try cutting back. Fact-check the claims you read, searching out sources that back up the science. Companies hold the job of labeling honestly—and people need to read those labels.

In my view, awareness ranks above habit. Folks who pay attention avoid many surprises. Choose moderation, know the potential effects, and the rest falls into place without needing to play food detective every meal.

How should Saccharin Calcium be stored?

Keeping It Away from Trouble

Saccharin calcium does a great job sweetening products without adding calories. I remember using it in my college chemistry labs, and the instructors always stressed the importance of storage. Everyone wants their product to last. Few appreciate how storage conditions end up making the difference between safe usage and a batch that doesn’t perform as expected. Moisture causes clumping and can degrade quality. Direct sunlight or heat alters the compound. Heat doesn’t just mess with taste; it can break down the molecular structure, making it unusable.

Simple Steps Make a Difference

A dry, cool storeroom changes everything. Manufacturers recommend storage below 25°C, and there’s science behind that number. Temperatures above that accelerate chemical reactions. Saccharin calcium starts to cake or pick up strange odors if left in damp, warm environments. Factories often use climate-controlled storage for this reason. Anyone who’s opened a sugar container that sat too close to the stove knows humidity ruins even the most stable ingredients.

Airtight containers make a world of difference. Every time you twist open a lid, the powder is exposed to air, and air carries invisible water molecules that quickly affect texture and purity. Using small, sealable jars at home keeps spoiling at bay. Industrial facilities seal larger drums with moisture-absorbing packets for good reason. There have been recalls in the past linked directly to poorly sealed powder. Even the U.S. Pharmacopeia lists moisture as a primary threat to food and pharmaceutical additives.

Contamination Concerns in Storage

Cross-contamination sounds like a far-off problem, but I’ve seen it happen in shared pantries. Saccharin calcium can pick up flavors and odors left behind by other chemicals or foods. Placing it away from strong-smelling items—like spices or solvents—keeps the sweetness pure. These are not abstract concerns. A 2022 report in the Journal of Food Science highlighted that trace impurities from nearby volatile substances showed up in quality control testing, affecting both flavor and safety.

At commercial scale, storage rooms include protocols to rotate older stock forward and check for leaks. Bags made from food-grade plastic, with a secondary paper layer, offer good insulation. When transported, manufacturers use pallets and keep containers off the ground where temperature and humidity swing wildly. At home, most people don't own warehouses, but a cupboard away from the stove works surprisingly well. Keep it off the floor, sealed tight, away from cleaners and spices.

Getting Rid of Waste

No one wants to think about throwing product away, but improper disposal can cause environmental harm. Small amounts can go in regular household waste, but larger quantities require responsible disposal based on local rules. Manufacturers and businesses turn to certified disposal companies for expired or contaminated batches. This doesn’t just protect people, it protects water sources and the wider ecosystem.

Attention to proper storage doesn’t just protect a product’s effectiveness. It reduces unnecessary waste and keeps sweetening agents safe and stable. Taking the time to store saccharin calcium away from moisture, heat, and contamination saves money, meets regulatory guidelines, and protects all who rely on it.

What is the recommended dosage for Saccharin Calcium?

Why Set a Dosage for Artificial Sweeteners?

People use artificial sweeteners for many reasons—cutting sugar, managing diabetes, lowering calorie intake. Saccharin calcium sits high on the list because it’s heat-stable and has a long shelf life. But concerns about how much to use aren’t just academic. High intake often links to potential health risks, so official guidelines step in to offer a safe middle ground.

The Facts on Saccharin Calcium Safety

The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) both address sweetener safety. They set what’s called an Acceptable Daily Intake, or ADI. For saccharin calcium, this sits at 5 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day. That’s a practical limit designed for long-term use, not a casual cup of tea.

Let’s put that into perspective: For a person weighing 70 kilograms (about 154 pounds), that’s up to 350 milligrams in a whole day. You’d need to drink a lot of sweetened beverages or eat quite a few sugar-free treats to hit the line. In a home kitchen, one might use a pinch for a pot of coffee or in a baking recipe. Commercial products tread carefully, measuring exactly so they’re well under that recommended ceiling.

Personal Awareness Counts

I once thought sweeteners would be an easy fix for sugar cravings, but I learned habits form fast. Our taste buds adjust—and expectations grow. Folks who load up artificial sweeteners sometimes crave even more sweetness in foods later on. And with saccharin, some experience aftertastes or stomach upsets at higher consumption levels, so keeping under the limit feels wise.

Reading food labels becomes a habit once you pay attention to daily intake. Sugar-free gum, diet sodas, yogurts—they add up. Changing brands or picking up a few extras at the store easily sneaks more sweetener into a diet than people realize.

Issues With Excess and What Can Help

Saccharin faced tough scrutiny decades ago when early data suggested a link to bladder cancer, mostly in rats. Later studies on humans didn’t show the same risk. Health agencies worldwide have since cleared it, but they stick with the ADI for safety’s sake. Some countries have specific labeling rules for saccharin-sweetened goods, so people can make informed decisions.

It’s easy to go overboard with any substitute, especially in groups working hard to avoid sugar. Providing clear consumer guidance helps tremendously. If food companies display how much saccharin calcium sits in a serving, people can watch their intake more easily. Doctors and nutritionists can play a big role too—offering practical advice on balancing real sugar, artificial sweeteners, and natural options.

Moving Forward

Relying only on artificial sweeteners doesn’t address all health concerns. Balanced eating habits, regular exercise, and personal monitoring make greater impacts. For those set on using saccharin calcium, moderation is the best approach. Understanding how much lands in your cup or plate gives back a bit of control, while sticking to science-backed guidelines keeps risk at bay.

Responsible use keeps food options open for people needing or wanting to skip sugar. Keeping one eye on dosage never hurts—it adds up without much warning. Staying informed and a little cautious gives everyone a safer experience.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Calcium 3-oxo-2,3-dihydro-1,2-benzothiazole-1,1-dioxide |

| Other names |

Calcium saccharin Calcium saccharinate Calcium salt of saccharin E954(ii) |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsæk.ə.rɪn ˈkæl.si.əm/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Calcium 3,4-dihydro-1,2-benzothiazole-1,1-dione-2-sulfonate |

| Other names |

Calcium saccharin Calcium saccharinate Saccharin, calcium salt E954(ii) Calcium salt of o-sulfobenzimide |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsæk.ə.rɪn ˈkæl.si.əm/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 6485-34-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 105226 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:47444 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201575 |

| ChemSpider | 21577411 |

| DrugBank | DB11195 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b7ee29-80a2-4371-8a42-efadfbcf1f33 |

| EC Number | 954-22-1 |

| Gmelin Reference | 18453 |

| KEGG | C14321 |

| MeSH | D020123 |

| PubChem CID | 24867631 |

| RTECS number | WN6500000 |

| UNII | U725D2574T |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 6485-34-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3560953 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:78050 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL2109537 |

| ChemSpider | 53455 |

| DrugBank | DB13283 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.447 |

| EC Number | 954-22-1 |

| Gmelin Reference | 151973 |

| KEGG | C14330 |

| MeSH | D020149 |

| PubChem CID | 24865873 |

| RTECS number | FC0525000 |

| UNII | 2J16SF10GX |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C7H4CaNNaO4S |

| Molar mass | 430.4 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.9 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble in water |

| log P | -0.18 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 11.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.08 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.666 |

| Dipole moment | 2.98 D |

| Chemical formula | C14H8CaN2O8S2 |

| Molar mass | 430.4 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.83 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.6 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 11.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.08 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.662 |

| Dipole moment | 4.74 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 437 J/mol·K |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1616 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −7084 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 297 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1615.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3589 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A10BX04 |

| ATC code | A10BX04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS labelling: "Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270 |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ (oral, rat): 18 g/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | > 17 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WZ2620000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 15 mg/kg bw |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS labelling: "Not classified as hazardous according to GHS |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Autoignition temperature | > 553°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 rat oral 7200 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 17 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WN6500000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 4.8 mg/kg bw |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Saccharin Saccharin sodium Saccharin potassium Saccharin ammonium |

| Related compounds |

Saccharin Saccharin sodium Saccharin ammonium |