Resveratrol: Layers of Discovery, Science, and Possibility

Historical Development

People have long valued plants both for healing and nutrition, but it took the scientific curiosity of the twentieth century to uncover many of the secrets hidden in vines, roots, and leaves. Resveratrol entered the scene when Japanese scientist Michio Takaoka isolated it from the roots of the white hellebore in 1939. Grapes and red wine came later as research broadened, drawing attention to diets in Southern Europe that seemed linked to healthier hearts, even with bread dipped in olive oil and plates of cheese at every meal. The so-called “French Paradox” caught the world’s attention in the 1990s, sparking fresh debate over the real role resveratrol plays. Over the decades since, studies have brought new layers to the story, showing both promise and confusion, as experts continue to measure the compound's true value.

Product Overview

Resveratrol shows up as a supplement, an ingredient in some cosmetics, and a favorite buzzword for lifestyle marketers reaching for credibility. It’s often sourced from the skins of grapes, root of Japanese knotweed, and berries. Commercial products often extract the trans isomer, which is believed to be more bioactive than its cis counterpart. Supplement capsules line health store shelves promising antioxidant and anti-inflammatory benefits, sometimes bundled with other polyphenols for a marketing boost. Powdered forms and food additives target manufacturers who want to give functional foods a premium label, leaning on the reputation resveratrol gained after years of press. In cosmetics, manufacturers prize it for the claims of skin renewal and “anti-aging” properties, although evidence for true age reversal remains thin.

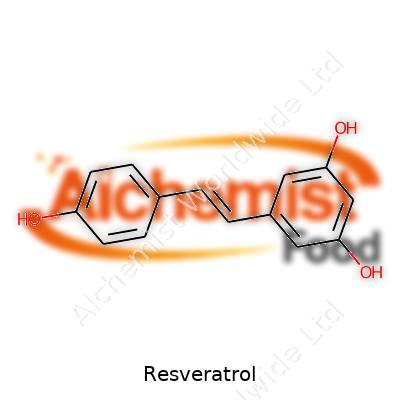

Physical & Chemical Properties

On the lab bench, resveratrol takes the form of a white to off-white crystalline powder. Chemists recognize its structure by three hydroxyl groups on a backbone of two aromatic rings joined by a double bond. It melts at about 253 °C. Water doesn’t dissolve it well, leading scientists and industry specialists to look at fat-based carriers or alcohol for solutions. The double bond makes it sensitive to light, heat, and oxidation—packaging and storage become more than just afterthoughts because mishandling strips away its potency. These traits influence both industrial processing and the design of clinical trials, since not all resveratrol in a supplement ever finds its way to the blood once swallowed.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers lay out purity, particle size, and source origin on certificate of analysis sheets. Pharmaceutical and food-grade standards expect upwards of 98% purity, with heavy metal and pesticide residues kept below tight thresholds. Labels in the U.S. follow FDA dietary supplement guidance, stating serving size, trans-resveratrol content, and a note clarifying that claims haven’t been evaluated by the agency. In the EU, names and quantities on packaging face stricter rules, focusing on both consumer safety and traceability under regulations for novel foods and cosmetics. Traceability plays out along each step, from farmers harvesting knotweed roots to batch records at facilities grinding extracted powder.

Preparation Method

Extraction often begins with dried grape skins or knotweed ground into coarse flake. Ethanol or methanol baths pull resveratrol from plant tissue. Filtration and evaporation steps concentrate the extract, which goes through further purification—often using column chromatography—to isolate the trans form. For large industrial batches, solvent selection walks a line between safety, cost, and efficiency, keeping residual solvents below regulatory thresholds. Synthetic routes use the Perkin reaction or Wittig reaction, but most industry prefers natural sourcing to meet consumer demand for “plant-based” origin on the label. After purification, the powder dries under controlled conditions before being packed into bulk containers or portioned into capsules, tablets, or small-dose vials.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Scientists tweak resveratrol’s structure to try and boost its bioavailability—adding methyl, acetyl, or glycosyl groups. These modifications increase solubility or change how the body absorbs and metabolizes the compound. Glycosides such as piceid occur naturally in some plants and release active resveratrol after enzymatic hydrolysis in the gut. Researchers in medicinal chemistry studios also make analogues, shifting hydroxyl positions or extending the carbon chain, with hopes of creating compounds that show stronger or more selective biological activity against inflammation, oxidative stress, or even specific cancer pathways. Some teams look at encapsulation in nanoparticles or emulsions, aiming to shelter resveratrol through the harsh stomach environment to improve delivery to target tissues.

Synonyms & Product Names

The name resveratrol appears on supplement bottles, but scientists might reference it as 3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene, embracing IUPAC convention. In pharmacological databases, synonyms include "trans-resveratrol" or "cis-resveratrol", and the abbreviation RSV finds use in both scientific and marketing materials. Plant sourcing leads to alternate names as “polygonum extract” or “Japanese knotweed extract.” Cosmetics trade uses creative product names like “youth grape concentrate” or “vino defense complex” to sharpen consumer appeal. On ingredient lists, transparency varies, and savvy consumers run into everything from “natural polyphenols” to precise chemical identifiers.

Safety & Operational Standards

Labs, factories, and packaging operators follow hazard statements and workplace exposure rules. Pure resveratrol in bulk powder form can irritate eyes, skin, and lungs. Material safety data sheets flag both acute and chronic exposure risks, though normal dietary intake from wine or berries remains safe for adults. During processing, air extraction, gloves, and goggles cut down on worker incidents. These efforts tie into broader food safety certifications, and companies chasing “clean label” status document every step from raw material traceability, to final third-party purity tests. Regulatory bodies in the U.S. and EU request safety studies and set allowable limits on solvents like ethanol, ensuring that commercial products don’t expose consumers to residues above established health benchmarks. Specialists monitor batch quality using HPLC and spectrophotometric tests, keeping records for auditing and recall compliance.

Application Area

Red wine headlines aside, most resveratrol finds its way into wellness supplements, sold on the strength of botanical tradition and modern antioxidant hype. Manufacturers of functional foods and drinks blend the compound into protein bars, yogurts, juices, and teas with an eye on heart health claims. The cosmetic world pursues its purported benefits for skin’s appearance, integrating resveratrol into lotions, creams, and serums, chasing demand for products that promise to offset signs of sun, age, or pollution exposure. In medicine, researchers and clinical teams evaluate resveratrol as an adjunct in diseases tied to inflammation or oxidative stress, including diabetes, neurodegeneration, and arthritis, though regulatory approval as a drug has yet to materialize. Agriculture even taps the power of resveratrol, breeding plants rich in the compound to defend against mold and pathogens.

Research & Development

University labs and biotech firms continue to map out resveratrol’s molecular pathways in cell culture and animal models. Research has zeroed in on signaling cascades involving sirtuins, AMPK, and NF-kB, tying them to aging and metabolic health. Animal studies report improvements in insulin sensitivity, reduced tumor formation, and neuroprotection. Translating these benefits to humans remains challenging, partly because the body breaks down resveratrol quickly. Teams now turn to analogues, combinations with other plant compounds, and novel delivery platforms to push clinical outcomes closer to preclinical promise. The field remains highly competitive, with patents filed on proprietary mixtures, encapsulation techniques, and process improvements that stretch from farm partnerships to bioavailability-boosted finished products. Funding trends suggest a rising tide of support for projects that take resveratrol beyond the supplement aisle, possibly into prescription drug territory.

Toxicity Research

Dose, duration, and purity drive risk. Studies using rodents and in vitro assays report low acute toxicity at doses well above what people typically consume, whether by eating grapes or popping a capsule. Mild GI complaints show up with higher doses in some human studies—nausea, stomach upset, and headaches come up most often. Scientists look for liver, kidney, and reproductive toxicity in animal chronic dosing, with most studies showing a wide margin of safety. That said, resveratrol interacts with some enzymes tied to drug metabolism, raising flags about its combination with prescription medications. Those with bleeding disorders or pregnant individuals stand among the groups for whom caution makes sense. Regulators urge manufacturers to follow good manufacturing practices and to support health claims with enough data to ensure the public doesn’t get misled about safety, especially when stacking resveratrol with other bioactive compounds.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the road for resveratrol splits in a few directions. The supplement market stays robust, but researchers want to solve bioavailability puzzles so more resveratrol reaches tissues where it may help. Ongoing clinical trials push product developers to refine dose forms, from sublingual drops to slow-release capsules. Regulators in major markets pay closer attention to claims, hoping to bridge the gap between preclinical enthusiasm and proven health benefits in humans. Genomic tools and big data may soon reveal which populations stand to benefit most, and which gene variants shape individual response. Food and beverage companies continue to experiment with resveratrol-fortified snacks and drinks, aiming to draw “better for you” shoppers while managing flavor and shelf life concerns. The cosmetic and pharma worlds look to resveratrol as more research clarifies whether molecular tweaks or new delivery systems can deliver the protective edge hinted at in animal studies, possibly reshaping how people think about prevention, aging, and healthy living for decades to come.

What is Resveratrol and what are its health benefits?

What Is Resveratrol?

Resveratrol shows up as a natural compound in the skins of grapes, some berries, and peanuts. Red wine features it most famously, thanks to the grape skins used during fermentation. This plant chemical belongs to a group called polyphenols, which help protect plants from injury and fungal attacks. Over the past few decades, researchers noticed how resveratrol seemed linked to better heart health among people who drank moderate amounts of red wine. That kicked off years of studies and a load of health claims—some more convincing than others.

The Heart Health Connection

People often point to the so-called “French Paradox”—the idea that French folks eat plenty of cheese and fatty meats but have relatively low rates of heart disease. One possible reason? The red wine at mealtime. Resveratrol stands out here. Studies in animals have shown it may help protect the lining inside blood vessels, reduce "bad" LDL cholesterol, and keep platelets from clumping together, which lowers the risk of blood clots. Human studies suggest there could be a connection, but the Mediterranean diet itself also involves loads of vegetables, fruits, and healthy fats, so the whole picture looks more complex than just a single ingredient.

Beyond the Heart: What Else Could Resveratrol Do?

Apart from heart health, some research points toward resveratrol’s anti-inflammatory and antioxidant powers. Scientists have looked at it for possible help with diabetes, memory loss, and even prolonging lifespan. One study out of Harvard showed that resveratrol triggered a gene linked to longevity in mice, sparking a flood of anti-aging claims. But that same splashy news must be balanced with human experience. In people, evidence runs thin. Large reviews haven’t found strong proof that supplements slow aging or sharply boost health in the average person.

Should People Take Resveratrol Supplements?

Walk into any pharmacy and you’re bound to spot resveratrol pills, each promising big benefits. Yet most of what science knows comes from animal or lab work. In people, studies often use higher doses than what shows up in food or red wine. The body doesn’t absorb oral resveratrol very well—most of it breaks down before it reaches the bloodstream in useful amounts. Health experts warn about treating it like a miracle fix. If someone already eats a nutritious diet full of fruits and vegetables, especially those with natural polyphenols, that offers broader protection than relying on one compound.

What Matters for Real-World Health

Eating a diet rich in plant-based foods delivers plenty of polyphenols, not just resveratrol. Blueberries, nuts, and grapes all bring benefits that go beyond a single nutrient. Drinking red wine in moderation seems safe for most adults, although too much alcohol quickly cancels any gain and brings serious risks. For folks taking blood thinners or who face specific medical conditions, supplements or even extra helpings of resveratrol might interact with their medications. It makes sense to talk with a healthcare provider before jumping into new supplements, especially for anyone with ongoing health concerns.

Strengthening Health Through Small Choices

Science shows nature often works best as a package deal. Relying on food sources, not just pills, remains the simplest way to get the mix of healthy chemicals the body appreciates. While excitement around resveratrol isn’t hype-free, its story fits into a larger lesson: small choices, such as eating a variety of plants, walking daily, and enjoying life’s pleasures in moderation, stack up to protect health for the long haul. That’s something worth appreciating more than any single “super-nutrient” headline.

Is Resveratrol safe to take daily?

Taking the Hype for a Test Drive

Resveratrol stands out as one of those supplements that people talk about at dinner parties, often right after a glass of red wine. Researchers first found it in the skin of grapes, which sparked lots of talk about the “French Paradox”—low rates of heart disease despite wine-rich diets. Plenty of folks jump on board, hoping for a shortcut to good health, but safety deserves real attention.

Why Safety Gets Real

Supplements flood the market, each vying for a spot in our morning routines. Resveratrol ranks high because of studies linking it to lower inflammation and even cancer prevention. Still, most of these claims start with animal studies or short-term human data. Taking a pill every day needs more evidence than what looks good in a petri dish.

The US Food and Drug Administration doesn’t treat supplements with the same scrutiny as prescription drugs. What you see on the label may not always match what’s in the bottle. Brands vary a lot in quality and dose, which matters since too much resveratrol can start to stress the liver and interact with blood thinners. If a doctor already prescribed medication for heart health, daily resveratrol can increase the risk of bleeding by bumping against drugs like warfarin or aspirin. Grapefruit doesn’t get along with many drugs, and resveratrol might behave in the same unpredictable way since the liver uses similar pathways.

Where Research Stands Now

Studies on daily resveratrol safety rarely last longer than three months. The biggest ones use doses between 150 mg and 500 mg a day, usually with few side effects in healthy adults. Nausea and stomach upset keep popping up as the most common complaints. Some mild headaches and diarrhea also show up, but nothing life-altering at regular doses.

People dealing with diabetes, cancer, or heart disease tend to feature in resveratrol research because these groups have more at stake. Unfortunately, long-term safety stays murky because most trials don’t follow people for years. Resveratrol’s promise comes with a data gap—especially for those with multiple health conditions or those taking several prescriptions.

Reading Between the Lines

My own experience comes from supporting loved ones looking for options besides statins or anti-inflammatory painkillers. Doctors I trust often point out that, despite the “natural” tag, resveratrol isn’t magic. Piling up supplements won’t make up for eating pizza every night and skipping vegetables. Real-world nutrition wins over shortcuts every time.

Making Informed Choices

Anyone thinking about adding resveratrol should talk to their healthcare provider—especially if chronic illness or daily prescriptions play a role. Getting the supplement from a reputable manufacturer with third-party testing helps cut the risk of surprises in purity and strength. Better to approach resveratrol as a piece of a bigger health puzzle, not a miracle fix.

If future studies show resveratrol can make a difference without hidden dangers over the long haul, it could move from boutique supplement to mainstream advice. For now, balanced eating, regular exercise, and honest conversations with doctors still deliver the best odds for healthy living.

What is the recommended dosage of Resveratrol?

The Buzz About Resveratrol

Resveratrol seems to pop up everywhere – from health store shelves to headlines promising a longer life thanks to a molecule found in red wine. People often ask how much to take. Sorting through the claims matters, since chasing after longevity should come with real-world evidence.

The Dosage Question

Doctors and researchers don’t see eye-to-eye about the ideal daily dose. Most of the studies looked at doses ranging from about 100 milligrams to over 1,000 milligrams per day. In real life, far lower quantities exist in food. You’d need to drink countless bottles of wine to match even the lowest supplement levels used in research. Typical resveratrol supplements sold to the public come in doses of 100 to 500 milligrams per capsule.

Listening to the Science

Based on clinical trials, a daily dose of 150 to 500 milligrams appears quite common in supplement regimens. Researchers have seen some benefits with doses in this range, such as improved cholesterol numbers or reduced inflammation. High doses around 1,000 milligrams brought more side effects — upset stomach, headaches, and at times even increased liver enzymes. So, more isn’t always better.

How the Body Handles Resveratrol

Taking large amounts at once often means the body just gets rid of most of it before it can really do anything. The liver processes and flushes it pretty quickly. That quick elimination explains why scientists struggle to prove resveratrol helps as much in people as it does in animal or test tube experiments. Real benefit likely comes from consistency, not from mega-doses taken once in a while.

Does Everyone Need It?

Some experts say healthy eating should provide enough without pills. People eager for a specific heart, blood sugar, or anti-aging advantage turn to supplements hoping for extra help. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration doesn’t regulate these supplements as strictly as prescription drugs, so quality can change from one bottle to the next.

The Safety Factor

Doctors usually call resveratrol safe in the short term at moderate daily doses. Anyone on blood thinners or with bleeding disorders should keep their distance, since resveratrol seems to make blood less likely to clot. People with hormone-sensitive conditions might want to avoid it, too. Chatting with a doctor before jumping in makes sense, especially for anyone on medication.

Finding the Balance

Few Americans get anywhere close to high supplement levels from food. A bunch of grapes or a glass of wine gives less than five milligrams. People looking to supplements should stick to the lower end—say, 150 to 250 milligrams per day—unless working with a doctor monitoring for side effects.

Research on resveratrol keeps changing. Chasing health fads rarely pans out. Better to put energy into healthy eating habits than trust a single supplement to fix everything. If picking up a bottle sounds tempting, checking with a trusted medical professional will keep things safe and tailored.

Are there any side effects or interactions with Resveratrol?

Understanding Why People Pick Up Resveratrol

Resveratrol grew into a buzzword after researchers linked red wine and lower heart disease. Plenty of folks went looking for the benefits in supplement aisles, chasing hopes for longer life, better blood sugar control, and improved brain function. This compound comes from grape skins, berries, and peanuts, and it started popping up everywhere—capsules, drinks, even chocolate. People ask about side effects and interactions because natural doesn’t equal risk-free.

Stomach Troubles and Headaches

I tried a resveratrol supplement last year. Eager to reap the rewards, I didn’t expect it to upset my stomach. About an hour later, I felt cramps and thought it was my lunch. Turns out, mild stomach upset happens to others as well, along with diarrhea and headaches. Review articles from the Mayo Clinic and NIH mention that most people handle small doses well, but high doses—over a gram—tend to stir up more digestive irritation. Some even report dizziness or rashes.

Blood Thinners: Risk Worth Checking

Resveratrol acts like a mild blood thinner. If you take warfarin, aspirin, or even fish oil, this starts to matter. Mixing too many blood-thinning agents increases the risk of bruising and bleeding. I’ve seen patients at the pharmacy counter holding three bottles, not realizing they overlap in this way. Doctors now flag it, especially before surgery. One review published in Frontiers in Pharmacology cautions about combining supplements with prescription anticoagulants, because bleeding complications can sneak up.

Interactions with Other Medications

Resveratrol can mess with how your body breaks down medicine. The liver uses something called cytochrome P450 enzymes to process a lot of drugs—statins, anti-anxiety meds, certain blood pressure tablets. Resveratrol slows these enzymes in lab tests, so it could bump up levels of other medicines in your bloodstream. In practice, the effect seems small, though experts agree more human studies are needed. If someone already takes a handful of prescriptions, pharmacists recommend an extra check before starting anything new.

Affecting Hormones

Some animal research links resveratrol to shifts in estrogen levels, which draws attention for people with a history of hormone-sensitive cancers. There isn’t enough evidence yet in humans to call it dangerous, but oncologists still tell patients to use extra caution, just in case it acts on the same pathways as estrogen.

What Works for Real People

Discussion with a doctor or pharmacist remains one of the most reliable ways to cover gaps in supplement knowledge. Most side effects turn up when people overdo it with large doses that far exceed the amount found in wine or food. Pills on store shelves range widely in strength. Independent testing groups like ConsumerLab sometimes find labels don’t match the contents, so stick with reputable brands and look for third-party seals.

Smart Steps Moving Forward

Balancing benefits and risks takes honest conversations between people and their health care team. Choosing lower doses, timing resveratrol apart from prescriptions, and watching for warning signs like bleeding or major stomach upset gives people a safer shot at the benefits. Stories of mild headaches or gut irritation may not always show up on product packaging, but sharing those lived experiences helps everyone. Real trust builds through fact-sharing and transparency, not miracle claims promising the world in a bottle.

Can Resveratrol help with anti-aging or heart health?

A Closer Look at a Popular Supplement

Resveratrol sits in the middle of every conversation about anti-aging supplements. Walk into most health stores or browse online, and it's right there on the shelf, promising smoother skin, sharp memory, or a stronger heart. The buzz came after folks learned that red wine, a staple in some of the healthiest Mediterranean diets, is packed with this compound. Before tossing back a handful of resveratrol pills, it's worth breaking down what research and real-life experience actually reveal.

The Science Behind the Hype

Plenty of research teams set out to uncover secrets behind long life and a strong heart. In animal studies, high doses of resveratrol appeared to protect mice against some chronic diseases—especially those linked with aging. These findings led to an explosion of interest, but mice and people are worlds apart.

In human studies, the results come out less dramatic. A review in the journal Nature found little evidence that resveratrol pills extend lifespan or act as a cure for aging. Some trials reported a mild improvement in certain markers, like blood pressure or cholesterol. Daily doses in these studies usually needed to be pretty high—much more than anyone would get from a glass of red wine. So, munching on dark chocolate and sipping Bordeaux won’t deliver enough resveratrol to mimic those test tube miracles.

Heart Health and Lifestyle

Doctors usually talk more about balanced meals and regular walks than any single supplement. It’s hard to outsmart health basics, and it turns out whole foods work in ways isolated nutrients can’t replace. Resveratrol in red wine might play a supporting role, but nobody suggests drinking more wine for health. Other nutrients, plus the habit of social eating and active living, seem to matter just as much.

The American Heart Association stops short of recommending resveratrol pills. They point to lifestyle changes—think more fruits and vegetables, less processed food, and thirty minutes of movement most days—as the real heavy hitters for heart protection.

Risks, Supplements, and Smart Choices

Every pill sold over-the-counter falls under looser regulations than prescription medicine. Walk into any supplement aisle, and labels often stretch the truth. Some products don’t even match what’s on their own packaging, and the Food and Drug Administration doesn’t check every bottle before it hits store shelves.

For people on blood thinners or certain medications, resveratrol may bring some risks. Too much can slow clotting, which could lead to easy bruising or worse. Always talk to a doctor or pharmacist before starting a new supplement, especially if prescriptions or health conditions are already part of your life.

What Actually Helps

Aging well draws from the same advice most health professionals have used forever: eat real food, move your body, and manage stress. Antioxidants like resveratrol matter, but they work best as part of a bigger routine built around good habits. No single supplement can reverse time, but choices made at every meal and every day go further.

Health rarely boils down to one magic ingredient. For most folks, spending more time outside, prepping meals at home, and building strong relationships make a bigger difference than what’s inside any capsule. Simple steps win out over shortcuts in the long run.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 5-[(E)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]benzene-1,3-diol |

| Other names |

3,4′,5-Trihydroxystilbene trans-Resveratrol cis-Resveratrol |

| Pronunciation | /rezˈvɛr.ə.trɒl/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 5-[(E)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)ethenyl]benzene-1,3-diol |

| Other names |

3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene trans-Resveratrol Polygonum cuspidatum extract Japanese knotweed extract |

| Pronunciation | /rezˈvɛrə.trɒl/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 501-36-0 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3591692 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:27881 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL575 |

| ChemSpider | 7756 |

| DrugBank | DB02709 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.099.932 |

| EC Number | 1.14.14.161 |

| Gmelin Reference | 715545 |

| KEGG | C16516 |

| MeSH | D000072449 |

| PubChem CID | 445154 |

| RTECS number | SLB714350 |

| UNII | Q369O8926L |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5020185 |

| CAS Number | 501-36-0 |

| Beilstein Reference | 376925 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:27881 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1421 |

| ChemSpider | 5754 |

| DrugBank | DB02709 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.058.874 |

| EC Number | 1.14.14.149 |

| Gmelin Reference | 110492 |

| KEGG | C05996 |

| MeSH | D000072615 |

| PubChem CID | 445154 |

| RTECS number | SL1693000 |

| UNII | Q369O8926L |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5020183 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C14H12O3 |

| Molar mass | 228.24 g/mol |

| Appearance | Off-white to light brown powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.359 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | 0.03 mg/mL |

| log P | 3.1 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.0 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.58 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.56 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.529 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 2.47 D |

| Chemical formula | C14H12O3 |

| Molar mass | 228.24 g/mol |

| Appearance | Off-white to light brown crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.359 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | 3.1 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.0000001 mmHg (25 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.49 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.70 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.579 |

| Dipole moment | 3.2465 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 218.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -315.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3110 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 208.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -382.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3657 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX10 |

| ATC code | A16AX24 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GF, DF, SF, V, Ve |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315: Causes skin irritation. H319: Causes serious eye irritation. H335: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN. If you are pregnant, nursing, taking any medications or have any medical condition, consult your doctor before use. Discontinue use and consult your doctor if any adverse reactions occur. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0-🛢️ |

| Flash point | Flash point: >230°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 610 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): >2,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 2,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg |

| REL (Recommended) | 100 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GF, PF, SF, DF, V, Non-GMO |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302 + H312 + H332: Harmful if swallowed, in contact with skin or if inhaled. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep out of reach of children. Consult your healthcare provider before use if you are pregnant, nursing, taking any medication, or have any medical condition. Store in a cool, dry place. Do not use if safety seal is broken or missing. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0-H |

| Flash point | Flash point: >230°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 460 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): >2,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 2.0 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/kg bw |

| REL (Recommended) | 100 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Pterostilbene Piceatannol Polydatin Trans-stilbene ε-Viniferin Phytoestrogens Quercetin |

| Related compounds |

Piceatannol Pterostilbene Polydatin Viniferin Trans-stilbene Oxyresveratrol |