Propionic Acid: A Practical Look

Historical Development

Before propionic acid showed up in the laboratory, a lot of problems in food storage often meant more waste than anyone liked. Chemists back in the 19th century first picked it out from dairy products and started mapping out ways to make it on a larger scale. Once the stuff worked out as a food preservative, its value climbed fast. For well over a hundred years, both people and companies have relied on propionic acid to keep animal feed and bread from turning moldy, keeping plates and livestock troughs safer with less fuss. Today, the world cranks out millions of tons every year, thanks to processes that have gone from small beakers to reactors the size of a swimming pool.

Product Overview

This acid carries a sharp, pungent smell, a smaller cousin of familiar vinegar. Compared to many chemicals running through factories, propionic acid feels down-to-earth because it keeps mold and bacteria in check but doesn’t mess with what you eat. You can pour it straight or add it in various forms, depending if you’re in grain silos, bakeries, or paint shops. Techs, farmers, and bakers recognize the difference once it’s included. Regulators in almost every region recognize it as a safe addition when used as directed, and it often pops up in product labels for everything from preservatives to flavorings.

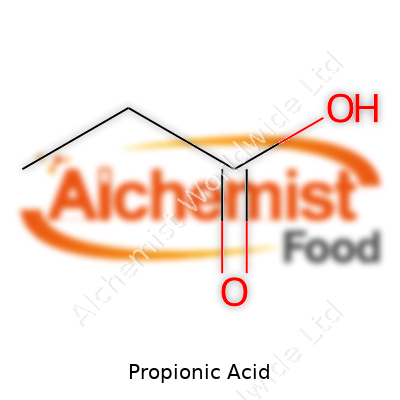

Physical & Chemical Properties

On the shelf, propionic acid comes clear and has a biting scent that’s hard to mistake, especially if you’ve handled acetic acid. Pour some in cold, and it stays liquid easily below room temperature. It boils just above that of water’s mark, and mixes all the way with water, ethanol, and a bunch of organic solvents. With a chemical formula of C3H6O2, this molecule behaves as a carboxylic acid, and can handle both acid-loving and base-loving reactions. Its density and reactivity make it suited for chemical processes that need a quick acid punch without the baggage of bigger, heavier molecules.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

You’ll see food grade and industrial grade as the two main choices, and both prickle the skin if spilled. Purity usually lands at 99 percent or higher, which researchers check using titration and chromatography. Producers stamp containers with UN number 3463, batch codes, hazard warnings, and handling instructions. In practice, every tank and drum wears both a product name and hazard icon, enforced heavily anywhere regulators have jurisdiction. If you’re doing quality control or tracking a batch through customs, these details are more than just a paper chase; wrong specs lead to product recalls or fines.

Preparation Method

Large companies tend to lean on either petrochemical or fermentation routes. Most propionic acid comes from hydrocarbons, especially through the hydrocarboxylation of ethylene. The other route starts with bacteria, like Propionibacterium, chomping away on a sugar or glycerol source in a tank. Both paths turn out a strong product, but fermentation keeps cropping up as a sustainable option, especially as feedstocks move away from fossil fuels. Each method calls for refined distillation and purification, otherwise impurities can throw off both shelf life and application in sensitive uses.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Propionic acid plays well with a broad roster of chemicals. It makes esters, salts, and can help produce useful building blocks like propionates for pharmaceuticals and plastics. The acid group opens doors: combine it with alcohols and you’ll get esters fit for flavors and fragrances. Propionic acid can take up chlorine to make propionyl chloride, or hook up with bases for salts that stay solid in the heat and damp of animal feed bins. Companies keep tinkering with new derivatives, aiming for fresh flavors, more potent preservatives, or improved industrial solvents.

Synonyms & Product Names

Most folks in the lab call it propanoic acid, while labels in the feed business list it as E280 in the EU. You’ll catch names like carboxyethane, methylacetic acid, and propionic acid. Brand names sometimes surface, especially for food and feed blends, but in chemical supply catalogs, only the pure name and batch counts.

Safety & Operational Standards

This acid demands respect in the workplace. Direct splashes burn skin and eyes, and the fumes can irritate airways—ventilation and gloves aren’t optional. Regulations in North America and Europe set workplace exposure limits, call for spill training, and force companies to keep emergency wash stations close to every filling line. In transportation, the acid rides in corrosion-resistant tanks with full containment measures in case a valve leaks. Routine audits and safety drills protect both workers and the public from avoidable accidents. In food use, strict limits keep daily intake far below levels that might spark health worries, with every load tracked from production to grocery shelf.

Application Area

You’ll spot propionic acid going to work in food preservatives, animal feed, pharmaceuticals, plastics, and even some herbicides. The most common spot in daily life is probably bread, where it blocks the molds that otherwise show up days before you finish the loaf. Farms use it to bale-proof hay and silage, pinning down moisture so animal feeds last until winter. Manufacturers count on it for plastics and solvents. As a feed preservative, it keeps grains fresh during storage, a key step wherever large-scale animal production depends on year-round supply. In pharma, propionates lead into drugs for everything from arthritis to anti-fungal applications.

Research & Development

Departments at universities and companies keep busy chasing both greener production and fresh options for derivatives. Fermentation keeps gaining ground, and researchers dig into new strains that thrive on waste biomass instead of grain, hoping for both cost savings and less competition with food sources. There’s ongoing interest in finding propionic acid replacements that work as well but cost less or run even safer. Efforts also dig into enzyme catalysts that promise cleaner, more targeted production, aiming to keep environmental loads low. New applications keep popping up, from biodegradable plastics to crop protection, pushing engineers and scientists to squeeze one more advantage out of a familiar chemical.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology teams have run tests on rats, rabbits, and cell cultures to map out margins of exposure and reaction. The acid’s sharpness mostly stays outside the body unless overdosed, and regulatory studies point to a wide safety margin for normal uses. Long-term animal studies don’t show cancer or major organ impacts at doses well above those found in preserved foods. Still, exposure above recommended limits in factories poses real risks: skin burns, breathing troubles, and eye injuries show up in accident logs. Food authorities check every batch for residues, and watchdog groups track new studies to catch any molehill before it turns into a mountain.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, propionic acid isn’t bowing out soon. Demand tracks with global population growth and the push for safer food storage, especially as weather swings and supply chains put more stress on crops. Markets for greener production continue drawing investment, with fermentation scaling up. Beyond the bakery, niche uses in biodegradable plastics, medical products, and novel agrochemicals could push demand higher. As more countries tighten food safety rules, technologies that get more preservative power from fewer chemicals likely get extra attention, keeping research dollars flowing and opening new doors for the sector.

What is propionic acid used for?

An Everyday Ingredient in Food and Farming

Propionic acid does its work quietly in a lot of places — grain silos, bakeries, cow barns, and maybe even your kitchen pantry. Anyone who has ever cleaned out a bread box knows what happens when mold gets out of hand. Foods spoil, profits drop, and producers lose sleep over recalls. Propionic acid steps in as a solution. It keeps mold and some bacteria from turning grain, bread, and cheese into science experiments. This acid gets added to animal feed and stored grain for the same reason — spoiled feed can sicken whole herds, and the losses pile up fast.

Years ago, I worked in a small bakery. Every baker kept an eye on shelf life. Bread with short shelf life means wasted effort and money, unhappy customers, and endless complaints about moldy slices. Using propionic acid, it became possible to keep bread fresher without pumping it full of sugar or salt. This acid works in small amounts, and it doesn't taste like a chemistry set. That turns out to be a real bonus, both for bakers and the people who eat their bread.

Farmers’ Friend and Food Safety Ally

On the farm, mold in stored grain can wipe out months of work. Propionic acid acts like a line of defense, slowing down spoilage after the harvest. Without it, feed grain faces rain, heat, and invisible spores that move fast. In the dairy industry, spoiled silage can run animals into the ground with illness and weight loss. Farmers learned to mix propionic acid into silage and stored feed, giving cows a fighting chance during rough seasons. Sick animals mean lost milk, vet bills, and even burned reputations if disease spreads. Keeping feed stable stretches the hard-earned harvest further and lowers risk all around.

Add to this the world’s growing focus on food safety. Companies must prevent mold before products leave the warehouse. If spoiled food makes it onto store shelves or dinner tables, lawsuits and ruined reputations follow. Propionic acid provides a proven, science-backed answer to this ever-present threat. Food scientists have found it works well alongside other acids and treatments, so producers can tweak recipes without breaking regulations or adding extra processing steps.

Health Considerations and Consumer Demand

There’s always a debate once a chemical with a tongue-twister of a name goes into food. In the case of propionic acid, safety reviews point out that it breaks down in the body into common compounds found in normal metabolism. Major food watchdog agencies, including the FDA and EFSA, have given it the stamp of approval when used in low concentrations. That said, transparency in food labeling matters. Companies have to keep informing people about what goes into processed foods and why. The push for “clean labels” urges suppliers to prove both safety and necessity.

Shoppers want to know what keeps their bread and grain fresh. Producers can boost trust with clear labels, backed by third-party safety findings. In an age where information moves quickly online, hiding behind jargon does more harm than good.

Charting the Future

Propionic acid fills an important gap between waste prevention and food safety. Focus turns now to smarter use, cleaner application methods, and greener production. Research keeps coming in, and so do demands for products with fewer additives. The sweet spot in modern food systems lies in using less to do more — and in explaining these choices to anyone who wants to know how their food is made.

Is propionic acid safe for human consumption?

Understanding Propionic Acid

Walk through any supermarket bread aisle, check the label, and you’ll often find propionic acid listed among the ingredients. It stops mold in its tracks, keeping baked goods fresher for longer. While that might sound a bit unsettling, this acid forms naturally in some cheeses and even in our own intestines, where bacteria churn it out as they break down fiber. It’s not some recent lab invention; it is part of how our digestive system works every day.

Recognizing the Science and Studies

Researchers have been paying attention to food additives like propionic acid for decades. Multiple studies funded by public health agencies and independent scientists have tested the safety of propionic acid. Toxicity evaluations in animals at high doses haven’t shown carcinogenic effects or genetic mutations. Authorities around the world—including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority—have reviewed all the data and continue to allow this acid in bread, cheese, some processed meats, and even animal feed.

Fears and Concerns

Despite the general green light from regulators, lots of people feel uneasy about seeing unfamiliar chemical names on ingredient lists. That comes from a reasonable place; trust gets shaken when a food label reads like a chemistry quiz. Some early animal studies hinted at links between propionic acid and behavior changes. That got picked up by news outlets and circulated through parent groups, especially among families concerned about food dyes and ADHD. Human data hasn’t supported those fears, though. The levels present in bread or cheese don’t build up in the body. Our livers break them down quickly, and any leftovers get flushed out in urine.

Practical Consumption and Daily Reality

Baked goods with propionic acid usually contain concentrations far lower than scientific thresholds. Eating a sandwich or a croissant now and then doesn’t push anyone toward danger territory. For people who stick to home-baked bread or shop at markets selling preservative-free goods, exposure drops even further. The occasional consumption of store-bought bread as part of a balanced diet remains safe for the vast majority of adults and children.

There are cases where sensitivity may crop up, especially in rare metabolic disorders. In conditions like propionic acidemia—a genetic defect—this compound doesn’t break down well, which brings serious symptoms. That’s an outlier situation and needs medical guidance, not a sweeping ban or dramatic headlines.

Weighing the Real World and the Way Forward

Instead of demonizing or blindly trusting anything with a chemical-sounding name, there’s wisdom in paying attention to quality dietary habits overall. Relying on processed bread or pastries loaded with additives day after day? That probably signals an underlying issue with access to fresh foods or a need to learn some simple baking skills—not that a food scientist has slipped poison into breakfast. Food safety authorities in many countries keep reviewing studies, and if new data showed harm from typical daily use, guidelines would shift.

For the time being, if labels make you uncomfortable, sticking with simpler foods or using a local bakery is always possible. Propionic acid doesn’t belong on a blacklist for most people, but it shouldn’t be a license to eat shelf-stable baked goods at every meal, either.

Make decisions based on balanced evidence, not internet scare stories or marketing slogans. Diverse diets rich in whole foods foster health a lot more reliably than any single preservative ever could.What are the storage requirements for propionic acid?

Why Proper Storage Matters

Propionic acid often shows up in food preservation and animal feed, and it’s a pretty common sight in chemical plants. Folks handling this compound already know it has a strong, unpleasant odor and can burn the skin or eyes if not managed with caution. Few realize just how much overlooked storage issues cost both in lost product and safety risks. Over the years, stories have come up where leaks and poor ventilation led to serious worker injuries and expensive fines.

Effects of Material and Temperature

Propionic acid reacts aggressively with common metals. Storing it in steel drums turns into a disaster if moisture finds its way inside; corrosion sets in, and the next thing you know, there’s contaminated product or leaks. Well-sealed, corrosion-resistant containers—usually polyethylene or stainless steel—prove far more reliable over time. These containers should stay out of direct sunlight, partly because heat speeds up evaporation and partly because build-up of fumes inside a warm storage shed creates a breathing hazard.

From first-hand experience, placing propionic acid in a poorly ventilated, cramped storeroom leads to headaches and coughing fits within minutes if someone opens a drum. Nobody wants to work in those conditions. Proper aisle spacing and ventilation—ideally mechanical exhaust fans that replace air several times per hour—go a long way to keep levels safe for workers. Public incidents, including reports from OSHA, often trace back to a lack of fresh air inside storage areas.

Segregation and Leak Control

Mixing storage of acids and bases creates more problems than it solves. Spills or leaks that mix with incompatible chemicals can trigger reactions producing heat, toxic gases, or flammable fumes. This isn’t just theory—it’s played out dozens of times, with emergency teams hustling to contain what began as a minor leak. Propionic acid stays far safer if it remains in a separate, clearly marked area, well away from oxidizers and strong alkalis.

Spill Response and Fire Safety

Cleanup crews handle most acid leaks by placing dry earth or sand around spills, then clearing it out for hazardous waste disposal. Small leaks might sound trivial, but even a small puddle can burn through protective gloves that aren’t rated for acids. Modern facilities keep neutralizing agents like sodium bicarbonate nearby, alongside spill kits, chemical splash goggles, and acid-resistant gloves.

Fire risk doesn’t disappear just because propionic acid isn’t classed as highly flammable—its vapors catch fire with the right spark. Good practice means keeping ignition sources, such as electrical panels or smoking areas, well away from storage locations. Safety Data Sheets show that its flash point sits fairly low, which means even mild heat or static discharge in confined spaces can cause trouble.

Practical Steps for Compliance and Longevity

Facilities storing propionic acid take regular inventory of containers. Labels need to remain clear so no confusion arises under stressful situations, like during an accidental spill or fire. Routine inspections check for corrosion, leaks, and aging of plastic drums—any sign of weakening calls for prompt replacement. Training programs for warehouse staff often run yearly, not only to meet legal requirements but because new employees need a practical guide beyond what’s on paper.

Storing propionic acid well requires thoughtful site design and a commitment to safety. Investing in the right containers, ventilation, and spill response tools saves a lot more than it costs. The value shows up in better worker health, less product loss, and a smoother day-to-day operation.

What industries commonly use propionic acid?

Food Industry Keeps Bread Fresh

Anyone who likes fresh bread probably owes more to chemistry than they realize. Propionic acid shows up in bakery products, cheeses, and even some processed meats. The main reason: it slows fungus and mold, cutting down on food spoilage. In my early days working with small bakeries, bakers mentioned how just a little of this additive could double the shelf life of a loaf. Besides bread, some cheeses use it for the same reason, helping cheese wheels stay edible longer and survive transport.

Animal Feed Production Counts On Protection

Animals on large farms get feed that needs to last through humid summers and long winters. Propionic acid helps protect feed from mold growth, which can ruin whole silos and cause massive financial loss. Livestock owners aren’t just saving feed; they’re making sure animals don’t eat anything dangerous. After years around rural feed mills, I noticed how dusty grain without these additives could get—and how quickly mold could take over. Not only does the propionic acid fend off spoilage, but it means farmers can trust their investment doesn’t rot away before animals eat it.

Pharmaceuticals And Preservatives Walk Hand In Hand

Drug makers use propionic acid during some chemical syntheses, especially for medications where purity matters. While it doesn’t end up in every finished pill, it does a quiet job in the background, shaping certain antibiotics or anti-inflammatory drugs. In the case of topical creams and gels, it can even stop the product from breaking down on the shelf. While patients rarely think about what stops skin ointments from spoiling, quality and safety standards in these industries are strict for a reason—contamination means risk.

Herbicides and Other Chemical Manufacturing

Agriculture leans on dozens of chemicals, and propionic acid plays a part in a few herbicides. Pesticide production often calls for small, reactive molecules, and this acid fits in more industrial formulas than people might imagine. Chemical plants put these components together under tight control, building the kind of agricultural tools that protect crops or clean up weeds. While some worry about the use of chemicals in food production, the strict guidelines for handling and application are there to protect both farmers and the land.

Personal Experiences Shape Perspectives

In my own cooking experiments, I’ve seen how bakery muffins go moldy within a few days in humid weather, unless treated. Meeting feedlot operators when I traveled through the Midwest, stories about lost crops due to mold were all too common—one summer of wet weather, and entire investments could disappear. Factoring in the pharmaceutical world, my conversations with pharmacists convinced me of just how much chemistry quietly supports public health.

Safer Handling and Room for Better Solutions

As with any strong chemical, safety in handling propionic acid cannot be overlooked. Industrial workers need the right gloves, masks, and training to avoid exposure. While many want to cut preservatives, the real question becomes how to keep food and feed safe if we move away from these time-tested solutions. Research continues into natural alternatives—certain plant extracts show promise, but cost and consistency remain challenges. Open communication between regulators, scientists, and industry players often leads to safer, smarter practices.

What are the physical and chemical properties of propionic acid?

The Plain Facts About Propionic Acid

Propionic acid turns up in labs, food factories, and across farmland, yet few outside those circles recognize it. This short-chain fatty acid shows up as a colorless liquid, with a sharp, almost pungent smell that calls to mind body odor or vinegar crossed with Swiss cheese. Some call it “propanic acid,” although most stick to the propionic label.

Chemically, propionic acid carries two carbons bonded together, topped by a carboxylic acid group. It stands somewhere between acetic acid and butyric acid—never quite as volatile or strong-smelling as the one, not as harsh or greasy as the other. These simple molecules shape how the acid reacts with water and with other substances, becoming a player in the shelf-life of bread, preservatives for animal feed, and as a growth inhibitor for molds.

What Sets Propionic Acid Apart

From the moment you open a container, the odor tells you this isn’t some background solvent. Anyone who’s worked around feed silage or in the flavor industry remembers the smell; you don’t forget it soon. Its boiling point hovers around 141 degrees Celsius—higher than acetic acid—so spills on your bench top don’t evaporate in minutes and linger in the air. Still, it dissolves easily in water, ethanol, and ether, making it versatile for food scientists and industrial chemists. This mix of volatility and solubility turns propionic acid into a keystone for safe food storage, slowing down spoilage organisms far better than some older treatments.

Working with acids always means handling with care. Propionic acid won’t burn straight through your gloves, though it causes burns and irritation with enough exposure. Getting splashed feels as rough as a vinegar burn, but a quick rinse and some common sense head off problems. Without safety steps, repeated handling brings headaches and lung irritation—common issues in cramped labs before fume hoods came in or when farmers mix preservatives into silage sheds.Older research from the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry highlights how even small doses keep bread mold-free days past untreated loaves. That niche—preserving bread—has kept propionic acid in commercial bakeries and on the ingredient lists for decades. In nature, bacteria in the gut and in Swiss cheese operations generate propionic acid as a byproduct, no chemistry degree needed.

Safety and Environmental Impact

Concerns surrounding acids often center on health and environmental spillover. Propionic acid doesn’t create persistent problems in soil or water, mostly breaking down safely in the presence of air and sunshine. Regulatory watchdogs, including the Food and Agriculture Organization, continue to clear it as a safe food preservative when kept to reasonable concentrations.

While demand keeps rising for “clean label” preservatives, bread-makers and feed producers find it tough to skip propionic acid. Its strong antimicrobial punch and easy compatibility with food processes keep it on top, despite newer organic acids hitting the market. From my experience, switching to alternatives means higher spoilage, more expensive ingredient sourcing, and, for some, a nostalgia for the days before “no chemical-sounding names” shaped the conversation.

The Search for Better Solutions

The food sector keeps scanning for new ways to fight mold without sacrificing shelf life or hiking up prices. Scientists test plant extracts, or blend acids in low doses, hoping for a perfect solution. So far, nothing knocks propionic acid from its position. Recognizing its strengths and limitations, while handling it with respect and knowledge, looks smarter than simply chasing labels.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | propanoic acid |

| Other names |

Propanoic acid Methylacetic acid Ethylformic acid Propionate |

| Pronunciation | /proʊˈpiː.ɒn.ɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Propanoic acid |

| Other names |

Propanoic acid Methylacetic acid Ethylformic acid Propionate |

| Pronunciation | /proʊˈpiː.ə.nɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 79-09-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | Beilstein Reference: 1720249 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30779 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL730 |

| ChemSpider | 565 |

| DrugBank | DB00163 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03-2119432645-48-0000 |

| EC Number | 200-835-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 971 |

| KEGG | C00163 |

| MeSH | D011345 |

| PubChem CID | 1032 |

| RTECS number | UJ8750000 |

| UNII | X045WJ989B |

| UN number | UN1844 |

| CAS Number | 79-09-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1900223 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30779 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1047 |

| ChemSpider | 709 |

| DrugBank | DB00163 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03-2119471835-39-0000 |

| EC Number | 200-835-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 736 |

| KEGG | C00163 |

| MeSH | D011374 |

| PubChem CID | 1032 |

| RTECS number | UF6930000 |

| UNII | XF88ZOU4FV |

| UN number | 1276 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H6O2 |

| Molar mass | 74.08 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid with a pungent, unpleasant odor. |

| Odor | Pungent odor |

| Density | 0.992 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | miscible |

| log P | 0.33 |

| Vapor pressure | 3.8 mmHg (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.87 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 11.35 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -47.5×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.386 |

| Viscosity | 1.19 mPa·s (at 25°C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.73 D |

| Chemical formula | C3H6O2 |

| Molar mass | 74.08 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless liquid with a pungent, unpleasant odor |

| Odor | Pungent |

| Density | 0.99 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| log P | 0.33 |

| Vapor pressure | 3.8 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.87 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 11.36 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -34.5·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.386 |

| Viscosity | 1.28 mPa·s (at 25°C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.50 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 152.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -425.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | –1527.1 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 152.3 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -425.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1525.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A07AA07 |

| ATC code | A07AA07 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS02,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H226, H314, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | H314, H335, P260, P264, P280, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P312, P321, P363, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-3-2 |

| Flash point | 129 °F (54 °C) |

| Autoignition temperature | 485 °C |

| Explosive limits | 2.1–12.1% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ (oral, rat): 2600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 2600 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | PR6400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 ppm |

| REL (Recommended) | 5000 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 1500 ppm |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS02,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H226, H314, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P210, P233, P260, P264, P273, P280, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P311, P312, P321, P363, P370+P378, P403+P235, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-2-2-Acid |

| Flash point | 53 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 485 °C |

| Explosive limits | 2.1–12.1% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 2600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 2600 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | WA6085000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL = 10 ppm |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.5 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 150 ppm |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Acetic acid Butyric acid Formic acid Valeric acid Isobutyric acid |

| Related compounds |

Acetic acid Butyric acid Valeric acid Caproic acid Isobutyric acid Isovaleric acid |