Potassium Sulphate: Looking Beyond the Label

Historical Development

Potassium sulphate first popped up in the historical records around the eighteenth century, when chemists began isolating minerals for fertilizers, gunpowder, and glassmaking. Early work depended on recovering this salt from the residue of mineral springs and volcanic soils. My own curiosity with potassium sulphate started at a local farming co-op. Old-timers there described truckloads arriving each planting season, long before digital crop planners and satellite advice. Even small communities knew the value of what they called “sulphate of potash,” and as agriculture scaled up after World War II, commercial processes replaced the old mineral springs, feeding the growing appetite for reliable plant nutrition.

Product Overview

Potassium sulphate’s role in farming runs deep. Primarily, it’s a fertilizer, giving plants two nutrients many soils don’t provide in large enough concentrations—potassium and sulphur. In my experience working with both conventional and organic growers, crops like potatoes, tobacco, and fruit trees draw big benefits because potassium strengthens cell walls and sulphur keeps metabolism humming along. The food and pharmaceutical industries also value the compound for quality controls and low-chloride content.

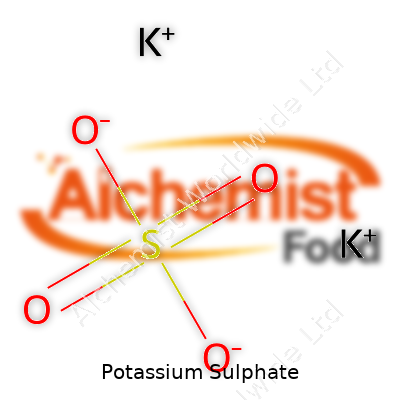

Physical & Chemical Properties

Potassium sulphate forms small, white, odorless crystals that dissolve easily in water. Chemically, you find K2SO4. Its melting point soars above 1,000°C, and it doesn’t react much with air or sunlight. Unlike potassium chloride, it won’t leave a salty taste or stress out salt-sensitive plants. That’s a lesson any greenhouse manager will learn quickly. Potassium sulphate resists breaking down in storage, doesn't clump under ordinary humidity, and dissolves right into irrigation water or spray tanks.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Most commercial potassium sulphate contains over 50% potassium by weight, usually expressed as K2O, and at least 17-18% sulphur, often as SO3. Labels matter in this sector, as regulations require clear declaration of purity, maximum permissible heavy metals, and solubility rates. Decades in ag supply taught me that mislabeling leads to poor results and costly crop loss. Certified suppliers tend to provide specs on particle size distribution, caking tendency, and chloride levels, the last being especially important in fruit and vegetable production.

Preparation Method

The majority of potassium sulphate today comes from two main processes. One route treats potassium chloride with sulphuric acid, yielding potassium sulphate and hydrochloric acid as a by-product. Another taps mineral ores like langbeinite or kainite, refining them with water and recrystallization to leave purified potassium sulphate. Each method brings unique advantages and waste streams. Mining operations near major deposits in Germany, Canada, and the U.S. supply much of the world market, while the synthetic approach mainly serves high-purity or pharmaceutical grades.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Potassium sulphate belongs to a family of stable salts. You can’t easily oxidize or reduce it under farm conditions, so tanks and spreaders do not corrode quickly. It reacts with barium chloride in labs to produce barium sulphate, a telltale white precipitate, often used in chemical analysis. Industry modifies the product for different uses—coating granules, adding trace elements, or making slow-release blends to fit specialty crops. These tweaks improve timing, reduce loss, and target unique soil challenges.

Synonyms & Product Names

Ask a grower about potassium sulphate and you might hear “SOP,” “sulphate of potash,” “arcanite,” or “patent kali.” Food processors sometimes list it as “E515,” since the European Union allows its use to adjust mineral content in foods. Labels from international suppliers usually include local language variations. Years in distribution showed me that checking names avoids confusion across border shipments and regulatory checks.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling potassium sulphate rarely brings serious risks as long as you stick to the basics. It doesn’t burn or explode, and it breaks down easily in water. That said, dust in the eyes or lungs can irritate, so warehouse staff and applicators use gloves, goggles, and ventilation. Modern storage sites keep the product in sealed bags or bins, out of direct rain, to stop any runoff or waste. The most critical risk comes from improper mixing with ammonium nitrate fertilizers—heat or nitrogen gas can prove dangerous. Industry regulations push for regular training, safety sheets, and clear labeling at all stages.

Application Area

Agriculture dominates the potassium sulphate market. High-value crops—vineyards, citrus, tomatoes, and cotton—depend on it for better yield and quality, often in soils already salty or with a heavy irrigation load. Greenhouse tomato growers rely on it to control nutrient ratios and limit chloride. Landscape and golf-turf crews spread it for lush, healthy greens where chloride-based fertilizers cause burn. The food industry uses potassium sulphate in cheese-making and wine production to adjust trace mineral balances. Recent growth in specialty chemicals taps the compound in glassmaking, pharmaceuticals, and animal feed. My time with land restoration projects showed its role in seedbed preparation for forest and prairie recovery.

Research & Development

Recent research explores molecular tweaks that might reduce potassium run-off from fields, bring better uptake by plants, and shrink the environmental footprint. Universities and crop science centers run trials on blending slow-release potassium sulphate with organic amendments such as compost or biochar. Some groups look at nano-coatings or delivery methods that might cut losses to dew or rain after application. Soil microbiologists want to better understand how root microbes help crops absorb both potassium and sulphur from applied fertilizers. These research streams feed into better yield, lower costs, and less water pollution for the next decade of farming.

Toxicity Research

Potassium sulphate stands out for low toxicity. Food safety authorities have repeatedly rated it as generally safe, even with regular dietary exposure, because the body handles potassium and sulphur well under normal conditions. That said, high doses bring problems—too much potassium can upset heart rhythms, and excess sulphate has a laxative effect. Livestock studies in scientific journals report that adding potassium sulphate beyond nutritional needs stunts growth and stresses kidneys. EPA guidelines urge runoff management and restricted access near streams or lakes, since concentrated solutions harm aquatic creatures.

Future Prospects

Growing pressure on farmland, fresh water, and sustainable agriculture will likely push potassium sulphate into new spotlight positions. Plant breeders are shifting toward varieties that need less chloride or cope with drier soils, while regulators demand tighter nutrient runoff controls. I expect technology to drive new products, coating each granule for longer release, or blending with micronutrients farmers usually ignore. Smart irrigation platforms might tune nutrient doses based on real-time soil tests. On the energy side, some researchers are testing potassium-based battery electrolytes that need ultra-pure materials. If climate change or market shocks disrupt potash supply chains, alternatives like potassium sulphate could become more than just one option on the fertilizer menu.

What is Potassium Sulphate used for?

Potassium Sulphate: The Quiet Backbone of Agriculture

Working on a family farm in my younger days, I spent early mornings moving sacks of different fertilizers. The dusty bags often bore names I barely paid attention to, but Potassium Sulphate kept appearing near the citrus groves. After years working with growers, I learned why it claims prime shelf space. Potassium Sulphate—also known as sulfate of potash—keeps food growing with vitality, especially in soils that can’t stand up to salty additives.

Feeding Plants Without Extra Salt

Crops need potassium to thrive. A lack of potassium makes leaves yellow around the edges and reduces the size and sweetness of fruits. Unlike some cheaper alternatives, Potassium Sulphate adds no unwanted chloride. In regions with dry weather or soils sensitive to chloride, growers turn to it. Think of grape vineyards near the Mediterranean or lettuce fields in California’s valleys. The salt load from other products ruins yields. Potassium Sulphate fits right in, boosting storage quality of potatoes, sugar content in grapes, and shelf life in tomatoes.

Helping Specialty Crops and Soils in Trouble

Some crops treat chloride like a poison—avocados, strawberries, beans, even tobacco. Potassium Sulphate ends up as the go-to fertilizer. Local greenhouse workers will share stories about how the wrong fertilizer ruined an entire batch, burning roots beneath the soil surface. Using this product helps avoid those costly mistakes. If a field has already collected salt from years of heavy fertilizer use, Potassium Sulphate lets farmers get potassium back into the ground without making the problem worse.

Other Uses Outside Farms

On the technical side, Potassium Sulphate shows up in more corners than many expect. It helps in fireworks, especially those that put out a gentle lilac color, and also pops up in some glass manufacturing. Its effectiveness in industrial processes doesn’t steal the spotlight from its agriculture role, but these uses add up. Still, the demand from food growers dwarfs anything else.

Sustainable Choices in Today’s Farming

The cost of Potassium Sulphate runs higher, so many large farms watch budgets closely. But cutting corners seldom pays off. Crops like almonds, carrots and peaches fetch a premium price for taste, appearance, and shelf stability. More farmers have asked if they can rotate fields, cut water use or apply nutrients with pinpoint accuracy to make expensive fertilizers count. Precision farming tools help, but soil testing remains the straightforward way to pinpoint just how much to use.

What Farmers and Gardeners Can Do

Smart soil management leads the way. Test the land before applying anything. If you farm in ground that fears salt or raise a specialty crop, Potassium Sulphate solves problems without introducing new ones. Gardeners growing tomatoes in raised beds like that it leaves soil structure intact and doesn’t stain leaves. Local extension agents and crop specialists carry practical advice for mixing and timing that stretches each bag further, saving both money and effort.

Health, Food, and the Everyday Plate

Each time someone sits down for a meal with crunchy lettuce or a perfect peach, there’s a good chance Potassium Sulphate played a small role. Soil needs help staying productive after years of harvests. Growers pick products that match the climate, crop, and land. The right fertilizer—applied carefully—keeps soil balanced and food quality high. Potassium Sulphate doesn’t take the limelight, but its steady presence keeps fields productive and grocery store shelves filled with fresh produce.

Is Potassium Sulphate safe for all crops?

The Promise and Limits of Potassium Sulphate

Walking the aisles of any agro-chemical store, a bag of potassium sulphate always seems to catch my eye. Plenty of growers lean on it for good reasons. Potassium supports how crops handle stress, helps fruit size up, and keeps leaves strong. Sulphur in the mix gives an extra boost, especially to oilseed and leafy crops that crave it. Potassium sulphate comes in handy where soils show salty patches or chloride-sensitive crops need special care because, unlike potassium chloride, it holds back on the salt.

Crops That Thrive with It

In experience on different fields, citrus and grape seem to wake up with potassium sulphate. The reduced chloride content keeps their roots happy and avoids scorch. Root vegetables such as potatoes push out better yields and stronger flavor, since high potassium deepens their dry matter content. Fields of cabbage and onions also gain from the sulphur inside, avoiding those pale yellow leaves that point to a deficiency.

Crops That Struggle or Stall

Safety questions always arise in regions where the soil already holds plenty of sulphur or potassium. Crops like legumes, which fix their own nitrogen and often pull what they need from the soil, might not care for extra sulphur or potassium from fertilizers. Piling it on only drains wallets and can push the soil balance off. Some berries or peas get thrown off by a heavy hand here, winding up with poor tasting fruit or odd leaf burn.

Soil Health and Over-Fertilization

Every year, more farmers test their soil before scattering any bagged fertilizers. Too much potassium sulphate stacks up potassium levels, locks up magnesium, and causes calcium to drift down. Over time, that shift in minerals means crops struggle to take up what they need. Soil with high sulphate can also run into troubles with certain sensitive crops, especially in sandy, weakly-buffered areas. If the soil drains fast or a heavy rain sweeps through, sulphate leaches out and ends up in the water table, causing headaches for communities nearby.

Smart Use and Better Yields

It makes a big difference to learn how much potassium and sulphur a crop can use, and where the soil sits before making a decision. Extension officers often bring up leaf analysis and regular soil testing — those help spot problems before they show up on the crop. Experts from the International Fertilizer Association note that worldwide, 30 percent of potash fertilizer goes to crops that respond best to it, while the rest may see little benefit or even suffer from the wrong mix.

Solutions for More Sustainable Potassium Use

Alternatives do exist for raising crop potassium. Compost and manures, for example, offer a steadier drip of both potassium and sulphur, along with organic matter. Rotating crops and growing less chloride-sensitive varieties can take the edge off fertilizer costs. More farmers look to controlled-release products, which feed nutrients slowly and trim waste or environmental risk.

A bag of potassium sulphate won’t fit every field or every crop. Understanding the needs of each plant and what the soil delivers keeps everything in balance. Harnessing local knowledge, listening to the science, and choosing the right product at the right time leads to strong harvests without wasting money or harming the ground.

How is Potassium Sulphate applied to soil?

Potassium Sulphate: More than Just a Fertilizer

Growing up on a farm, I’ve seen how essential potassium sulphate can be to a successful crop. Crops like potatoes, berries, tomatoes, and nuts all crave potassium for strong yields and better resistance to disease. Plants also suffer from too much salt, so growers use this sulphate form instead of cheaper potash if the soil or the crop can’t handle extra chloride. Getting the right balance is tough work, but potassium sulphate steps up for sensitive fruit and vegetable plots.

Methods Farmers Use to Apply Potassium Sulphate

Direct application works fine for small gardens and specialty beds. Dusty powder or pellets get scattered across the soil surface and worked in with a hoe or tiller right before planting. On the larger fields, farmers load up the spreader with granules. These pellets don’t clump or fly off with the wind. The farmer simply drives over the rows, letting the machine throw a measured dose across the field. The next rain or round of irrigation washes potassium and sulfur into the root zone.

Some growers prefer to mix potassium sulphate into compost or manure piles before spreading. That way, both organic matter and nutrients reach hungry crops together. Leafy vegetables respond especially well to this blended approach. Another method relies on fertilizer injectors hooked up to drip irrigation lines. Growers run a solution of potassium sulphate through these pipes right to roots, which saves labor and cuts runoff. In greenhouses, it’s common to dissolve potassium sulphate in tanks that feed an entire hydroponic system. Tomatoes soak up what they need and nothing gets wasted.

Soil Testing Guides the Way

Making decisions on how much to use starts with a soil report. Extension agents dig in, scoop up samples, send them to the lab, and break down the results for local growers. If the report shows potassium levels running low, those farmers can target their application. A good rule of thumb usually sits around 100 to 200 pounds per acre for many vegetables, with less for crops that need lower rates. No two fields match perfectly, so listening to the land makes sense every time.

Looking Out for the Environment

Getting carried away with potassium sulphate doesn’t just waste money — it can leach nutrients out of reach or into waterways. If the weather brings heavy rain after topdressing, older soils with less organic matter could lose potassium faster. Smart farmers rotate crops, plant cover crops in winter, and test soil regularly. These steps help protect streams and maximize every pound of input.

The Next Chapter in Feeding the World

Global fruit and vegetable demand keeps rising, especially for food grown with fewer residues. Potassium sulphate plays a role here, supporting lower-chloride practices. Research stations and ag startups keep pushing for more efficient fertilizers and precision equipment that places nutrients exactly where crops reach for them. Some farms use drones to scan stressed spots so nobody dumps product where it’s not needed. Taking care with each input helps families grow not just more food, but better food — straight from healthy soil.

What is the recommended dosage of Potassium Sulphate?

Practical Application In Farming

Potassium sulphate shows up in fields all over the world. Walk through any farm where crops demand both potassium and sulfur—think potatoes, tomatoes, grapes, or any fruit tree. Farmers lean on this fertilizer to push up yields and improve quality, but the amount tossed onto the soil isn’t guesswork. Even a well-intentioned heavy hand can tip the balance, burning roots or harming the environment. That’s why agronomists custom-fit recommendations according to each crop’s needs, the soil’s own potassium content, and the expected rainfall.

What the Experts Recommend

Guidelines give a solid starting point. University extension programs in the US and Europe suggest applying anywhere from 100 to 300 kilograms per hectare for most fruit and vegetable crops. Grains and less potassium-hungry crops often see doses closer to 50–100 kg per hectare. For gardeners working a smaller patch, that means 20–40 grams per square meter over the season, split into two or three applications to avoid wasted runoff. Local lab soil testing matters—too much potassium won’t just wash away dollars, it can also compete with calcium and magnesium, weakening plant growth.

Sulfur and Potassium: Why Both Drive Crop Health

It isn’t just about potassium alone—the sulfate part brings sulfur, too. Sulfur helps plants make protein and supports disease resistance. Lacking it, leaves might look yellow or crops can come out stunted. In places with cleaner air and little industrial fallout, sulfur shortages now pop up more often, pushing potassium sulphate to the front over classic muriate of potash. Soil tests tell you if your patch of land needs both nutrients or only one.

Potential Risks of Overdoing It

Every grower wants bigger harvests, but doubling the fertilizer rarely translates into double the fruit. Applying too much potassium sulphate not only wastes money, it can burn sensitive roots, especially in dry weather. Excess potassium can even lock out other key minerals. Farmers juggling livestock manure, compost, and chemical fertilizer sometimes see unbalanced fields because each source brings a different mineral mix. Balance matters much more than brute force.

Pathways to Smarter Use

With fertilizer costs climbing, a shovel’s worth of soil is worth testing before spending a cent more. Reliable labs test both potassium and sulfur. Once results come in, match your spreader to what the land asks for—not just a one-size recommendation. Split applications to feed crops through the growing season instead of all at once. Cover crops and crop rotation help hold on to nutrients, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizer by recycling what’s in the ground.

What Consumers Should Remember

People worry about what ends up in the food they buy. Following science-backed dosage keeps crops healthy and food safe. Enforcement is key in commercial farming, with regulators watching nitrate and salt buildup in both soil and produce. For folks growing for their family or on small community plots, reading fertilizer labels and checking local advice can keep the dose just right. No one wants to see healthy produce ruined by one mistake with a measuring cup.

Final Word: Test, Don’t Guess

Having walked past wilting tomato plants in an over-fertilized garden myself, I know the disappointment first-hand. With food prices rising and weather patterns shifting, using potassium sulphate correctly makes a real difference—saving money, feeding families, and protecting the land for the next generation.

Does Potassium Sulphate affect soil pH?

Digging Into Potassium Sulphate

Across farms and gardens, potassium sulphate sprinkles into soils as a prized source of both potassium and sulfur. Many growers trust it, especially where high-value crops—fruits, nuts, vegetables—ask for cleaner nutrition without extra salts. Yet, plenty of talk goes around about how fertilizers shift soil pH. I’ve had my hands in the dirt for years, and pH swings often worry folks who have seen problems with other fertilizers.

Soil pH and the Fertilizer Question

Soil pH isn’t just a number. It shapes the rules for how roots grab hold of nutrients. Too much acid ties up key elements. Too much alkalinity—same problem, different players. A change of half a pH point changes everything for blueberries or potatoes. Most growers learn this fast. I watched a neighbor flood his tomatoes with ammonium-based fertilizer and end up with stunted plants. So the question really matters: Will potassium sulphate act like those acidic products or swing the needle another way?

What Science Says About Sulphate

Potassium sulphate, by its chemical nature, brings potassium (K+) and sulphate (SO42–) ions. These wash into the root zone, dissolving easily, and don’t stick around as residues. Here’s where science helps. Unlike ammonium sulfate or urea, potassium sulphate doesn’t give off hydrogen ions that acidify the soil. Studies from agricultural universities show the pH barely moves after years of normal potassium sulphate use. Most soils—the loams, clays, sandy bits—shrug off its arrival. Some alkaline soils nudge pH very slightly, but not enough for crops or microbes to care.

Comparing Fertilizers: A Practical View

Out in the field, a bag of ammonium nitrate cranks up the acid load, pushing soil pH down. Gypsum fixes sodium without harming balance. Manure dumps both nutrients and organic acids, sometimes unpredictably. Potassium chloride, a cousin to potassium sulphate, sometimes builds up salt levels and burns tips in salty ground. After seasons of side-by-side trials, potassium sulphate consistently keeps soil pH within safe bounds. Sulfur, in other forms, can bring unwanted acidification. Here, the sulfate form rides in smoothly, balancing without extra drama.

Managing Soil Health Beyond the Bag

Watching fields over time, soil health comes from a blend of practices. Crop rotation, cover cropping, and the right fertilizer choices all matter more than one single nutrient. For soils already leaning too acidic from years of ammonium use, liming works. For sandy ground prone to leaching, potassium sulphate feeds plants without driving pH down, keeping roots healthy and active. The only places where a grower might see some change—very low pH, low buffered soils, or heavy repeated applications—still don’t report wild swings in acidity when potassium sulphate comes into play. Extension agents share the same advice: soil test first, apply what you need, and track results every season.

Solutions and What to Watch For

Sustainable soil management calls for honest records. Growers get the best results tracking fertilizer rates, rainfall, and crop performance, then running soil tests every year or two. In my experience, potassium sulphate carries less risk than many alternatives. If concerns about pH come up, a simple lime application or organic boost can set things right. It’s about stewardship—working with the land and using science to guide each decision. This approach gives crops what they crave and lets pH rest easy, season after season.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Potassium sulfate |

| Other names |

Sulphate of Potash Sulfate of Potash Potassium Sulfate SOP Arcanite Dipotassium sulfate Potash of sulfur |

| Pronunciation | /pəˈtæsiəm ˈsʌlfeɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium sulfate |

| Other names |

Sulphate of Potash Sulfate of Potash Arcanite Dipotassium sulfate |

| Pronunciation | /pəˈtæsiəm ˈsʌlfeɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7778-80-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 'BCFCDS' |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:131526 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201592 |

| ChemSpider | 22975 |

| DrugBank | DB11038 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard 03-2119456842-40-0000 |

| EC Number | 231-915-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | K 218 |

| KEGG | C14468 |

| MeSH | D011096 |

| PubChem CID | 24507 |

| RTECS number | TC6300000 |

| UNII | VGB1JE14YW |

| UN number | UN 2460 |

| CAS Number | 7778-80-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `"JSmol model" string for Potassium Sulphate: K2SO4` |

| Beilstein Reference | 120873 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:32588 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201432 |

| ChemSpider | 8266 |

| DrugBank | DB09433 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard for Potassium Sulphate: 03-2119956246-36-0000 |

| EC Number | 231-915-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | K 379 |

| KEGG | C14364 |

| MeSH | D011104 |

| PubChem CID | 24507 |

| RTECS number | TC6605500 |

| UNII | V8ZED1ZSRM |

| UN number | UN 2460 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | K2SO4 |

| Molar mass | 174.26 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.66 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 111 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.1 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.5 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.495 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | K2SO4 |

| Molar mass | 174.26 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.66 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 11.1 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -0.94 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | > 7.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.70 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Weakly diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.494 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 174.1 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1437 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1367.0 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 174.1 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1436 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1437.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 Warning |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not classified as hazardous according to GHS. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep away from heat. Wear protective gloves/eye protection. Avoid breathing dust. Wash hands thoroughly after handling. IF INHALED: Remove person to fresh air and keep comfortable for breathing. IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of water. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 0-0-0 |

| Explosive limits | Non-explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat: > 2,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 6600 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SN1650000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 60-80 kg/ha |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. May cause eye irritation. May cause skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Potassium Sulphate is not classified as hazardous according to GHS; therefore, it does not have hazard statements. |

| Precautionary statements | Store in a dry place. Store in a closed container. Avoid breathing dust. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use only outdoors or in a well-ventilated area. Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/eye protection/face protection. |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 6600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 6600 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | TC9300000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 50 - 100 kg/ha |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sodium sulphate Ammonium sulphate Magnesium sulphate Calcium sulphate Potassium nitrate |

| Related compounds |

Potassium nitrate Potassium chloride Potassium carbonate Sulfuric acid Sodium sulfate |