Potassium Metabisulfite: A Deep Dive Into Its Story and Use

Historical Development

Potassium metabisulfite emerged from the vigorous exploration of chemical preservatives in the 19th century. It owes part of its discovery to the search for effective ways to stabilize food and beverages a century ago. Early winemakers, struggling with unpredictable spoilage, stumbled upon the power of sulfur-based salts, including potassium metabisulfite, as a means to keep wine fresh during storage. Chemical suppliers then picked up the mantle, refining manufacturing processes through the 1900s to meet the growing demand of the beverage industry and food preservation. Over time, improvements in chemical purity and production scale transformed it from a niche preservative into a standard tool for artisans and industries alike.

Product Overview

Potassium metabisulfite, often found as a white granular or powdery substance, brings a powerful punch to food safety and preservation. In food and beverage production, particularly with wine, cider, and beer, it holds a crucial spot. The chemical shields products against oxidation and fights off unwanted bacterial and fungal invaders. Some home brewers swear by it, appreciating its reliability for protecting batches both small and large. Handmade or industrial labels rarely do without it when long shelf life and clarity matter. Its popularity stands as a testament to the trust professionals and hobbyists place in its continued effectiveness.

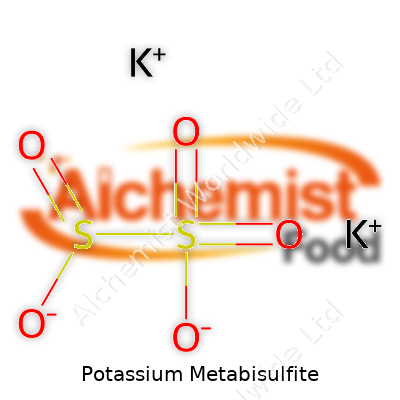

Physical & Chemical Properties

A glance at potassium metabisulfite shows a lightweight white powder, free-flowing but pungent, with a smell like burnt matches. Chemically, it counts on the K2S2O5 formula and dissolves with ease in water, transforming quickly to potassium bisulfite and releasing sulfur dioxide gas into the environment. That gas underscores its main strength — antimicrobial action — but demands care around enclosed spaces. It boasts a melting point near 190°C and demonstrates stability in dry conditions, although exposure to moisture prompts its signature chemical transformation. Every batch, regardless of use, leans on its chemical consistency to play its role in production.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Packaging for potassium metabisulfite often carries a content guarantee of over 95% purity, with strict tolerances for heavy metals and insoluble matter to meet food-grade standards. Labels bear hazard warnings: corrosive, irritant, strong oxidizer. Proper documentation addresses requirements for trace amounts of lead, arsenic, and other heavy metal contaminants. Food and beverage producers check for consistent particle size and confirm swift dissolution in laboratory water tests. Regulatory authorities mandate that labels clearly identify it as a food additive, typically under E224, providing transparency on usage limits for processed foods and wines. A reliable supplier meets or exceeds these benchmarks, as gaps here affect product safety and trust.

Preparation Method

Making potassium metabisulfite on an industrial scale relies on reacting potassium hydroxide or potassium carbonate with sulfur dioxide gas. Plant operators bubble sulfur dioxide through a solution until it saturates, then cool and evaporate the mix to drive out water content. At this point, potassium metabisulfite crystals emerge, ready for drying, sieving, and packing. Every step — strict temperature control, air monitoring, moisture management — shapes purity and yield. Plant managers guard against excess heat since decomposition will wipe out valuable product. While the core chemistry has changed little in decades, ongoing improvements in filtration and automation keep output consistent and costs manageable.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Potassium metabisulfite acts as more than just an additive. Mix it with water, and it quickly hydrates, breaking into potassium bisulfite (KHSO3) and potassium ions. Add acid, and you’ll get a strong release of sulfur dioxide, which plays the main preservative role. In the presence of oxidizing agents, it transforms into potassium sulfate and sulfuric acid residues. Wineries use it to bind acetaldehyde, a key player in spoilage. Once it interacts with oxygen or air for long periods, it loses activity, shifting into sulfate forms and shedding usefulness. So, users remain vigilant about storage and handling; once humidity or exposure ruins a batch, it’s time to start over.

Synonyms & Product Names

Potassium metabisulfite goes by many names, depending on industry or geography. Common synonyms include potassium pyrosulfite, E224, and K2S2O5. Food technologists often reach for “sulfite” or “meta” as short-hand. Chemical catalogs may refer to it as “dipotassium disulfite” or by product codes tied to purity and granule size. In brewing and winemaking circles, it’s “meta” or “wine stabilizer.” Whatever the business or label, these names funnel users to the same chemical — a recognized bulwark against bacterial and oxidative threat.

Safety & Operational Standards

Long experience with potassium metabisulfite taught producers and users to respect its hazards. The dry powder irritates skin, eyes, throat, and lungs on contact, and improper mixing produces choking sulfur dioxide fumes. Facilities handling it must install ventilation, keep dry eye-wash stations, and provide proper gloves and safety eyewear. OSHA and European REACH rules dictate exposure limits for airborne sulfur compounds in the workplace. Material Safety Data Sheets warn about accidental mixing with acids or moisture. Training extends from operators down to cleanup staff, so everyone recognizes symptoms — coughing, shortness of breath — and knows first aid. Anyone mishandling concentrated solutions rightfully faces fast enforcement and retraining since accidents can escalate quickly.

Application Area

Demand for potassium metabisulfite rises from its wide span of uses. The wine and brewing world leans heavily on it to squash microbial threats and control oxidation, preserving color and aroma. Dried fruit and vegetable packers dust it on produce to guard against browning. Photographers once used it to preserve developing baths. The chemical acts in the mining industry as a strong antioxidant, stripping unwanted impurities in ore processing. Textile operations harness it during dyeing to control unwanted oxidation that can wreck color quality. Smaller craft producers, home brewers, and even aquarium keepers look for it on store shelves, all searching out its chemical dependability to solve familiar problems.

Research & Development

Ongoing research explores better ways to deploy potassium metabisulfite in food tech, beverage stability, and industrial purification. Chemists tinker with blends that limit negative aftertastes in wines or control the trace contaminants that sometimes afflict fruit processed at scale. Start-ups in sustainable packaging hope to improve shelf life for dried goods by microencapsulating sulfites. Analytical scientists compare potassium metabisulfite with sodium metabisulfite, probing subtle differences in end-product aroma and residual taste. After working with winemakers, university teams run experiments on derivative compounds that may preserve without some of the sensitivity risks for asthmatics. Beyond food, researchers look into greener synthesis routes involving solar-driven processes or waste sulfur gas streams. Each step sheds light on smarter and safer applications that could soon filter into the mainstream.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology teams know the stakes with potassium metabisulfite, as sulfite sensitivity stands as a real problem for people with asthma or sulfite allergies. At normal use levels, regulatory authorities clear the compound as generally safe, but overexposure to sulfur dioxide or concentrated solutions brings health issues. Studies report respiratory irritation and, in rare cases, severe reactions in sensitive individuals, particularly after inhalation or ingestion of high doses. Regulatory agencies in the US and EU strictly enforce maximum allowable limits, and clear labeling serves as a shield for vulnerable consumers. Animal models and cell studies help illuminate the long-term impacts of chronic exposure, guiding policymakers on safe levels and prompting industry to push for responsible labeling and education for end users.

Future Prospects

The conversation around potassium metabisulfite heads in new directions each year, as food and beverage producers respond to growing market expectations for cleaner, additive-free labels. Biotech companies eye opportunities to engineer yeasts and bacteria that may produce their own preservative compounds, maybe reducing reliance on external sulfites in the long run. Wine and fruit processors put money into sensors to fine-tune dosage and limit free SO2 exposure. Environmental groups and green chemistry advocates press for reduced sulfur dioxide emissions in manufacturing cycles, pushing the sector toward more circular sourcing and energy-efficient reactors. If new consumer trends in natural wine and additive-free foods gain steam, potassium metabisulfite could see more application in cleaning up process lines and managing quality rather than as a direct food ingredient. People in the industry keep a close watch, knowing future changes in consumer safety rules or chemical regulation could call for big shifts in how they source and use this familiar but powerful product.

What is potassium metabisulfite used for?

The Many Roles of Potassium Metabisulfite

Potassium metabisulfite plays an important part in several industries. Talk to a winemaker, and the first thing you’ll hear is how it helps keep wine stable and safe. This white, crystalline powder helps prevent unwanted bacteria and wild yeasts from turning a good vintage into vinegar. Picture stacks of barrels in a cellar—each batch protected by just a pinch of this compound. Small wineries often handle challenging storage conditions, so they count on every bit of help for their wine’s flavor and clarity. Fewer off tastes means less waste and better business.

Beer brewers use it for similar reasons. Unwanted organisms can ruin a batch and hit the bottom line. Potassium metabisulfite acts like a gentle shield, giving the brew time to develop without interference. I’ve watched home brewers sweat over contamination in their kitchen setups—one misstep, and the whole carboy gets dumped. For those running a larger operation, losing hundreds of liters stings even more. Using preservatives seems like common sense.

Food and Beverage Preservation

The story does not end in the winery or brewery. Food producers count on potassium metabisulfite to keep fruit juices, dried fruits, and shellfish fresher for longer. Sulfites hold back browning and spoilage, making sure what reaches a market shelf still looks inviting. I remember packing dried apricots on my family’s small farm stand and being surprised at how quickly untreated fruit would turn. Customers trust that food is safe, and for people with allergies, knowing which products contain sulfites—thanks to clear labels—makes shopping possible. The labeling requirement isn’t just government busywork: it prevents some nasty allergic reactions, especially for asthmatics.

Water Treatment and Cleaning

Potassium metabisulfite lands a job in water treatment plants too. Some city water systems use chlorine to disinfect, but that chlorine needs neutralizing before the water gets used for certain processes or discharged into nature. This compound helps keep the process efficient and cheap, preventing environmental damage. If you’ve ever visited a facility where tap water gets recycled, you realize how critical these steps are for community health and the environment. Even small missteps can lead to contamination or fines for companies, so good chemistry matters as much as any filter or pump.

Risks and Moving Forward

Using potassium metabisulfite isn’t free from controversy. Some people react badly to sulfites. Public health bodies keep reminding everyone to read ingredient lists, and I’ve seen local food producers educate their customers with signs and explanations right on the market table. Allergies can make food producers nervous, but open communication and alternative preservation options (like refrigeration or vacuum sealing) give both businesses and shoppers more confidence.

Limiting use where possible, improving labeling, and investing in cleaner tech for water treatment could smooth out some rough edges. If producers and regulators keep listening to scientific research and real-world experiences, the benefits outweigh the risks. That’s how this simple compound keeps finding its way into more workplaces—quietly but surely protecting quality, flavor, and safety.

Is potassium metabisulfite safe to consume?

Understanding Potassium Metabisulfite

Walk into a winery or a homebrew shop, and you’ll spot potassium metabisulfite. This chemical gets sprinkled into everything from wine barrels to dried apricots. Its purpose? Killing bacteria and wild yeast, and keeping colors bright. If you track labels at your local grocery store, you’ll see it show up as E224. That code hides in the fine print on dried fruits, jams, juices, and plenty more. So the question isn’t just whether this ingredient works. The real concern—especially for people with allergies or asthma—centers on safety.

Sifting Through the Science

Over the years, regulators such as the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority have placed potassium metabisulfite on their “generally recognized as safe” or GRAS lists. Their confidence rests on studies with lab animals and people. At normal food levels, most bodies break it down pretty quickly, transforming it into harmless sulfate. That’s why the World Health Organization set an acceptable daily intake: 0.7 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. Most of us don’t even get close.

Allergy stories spook a lot of folks. For some, a plateful of sulphite-laced dried apricots can trigger wheezing, hives, or stomach cramps within minutes. These “sulphite-sensitive” people react to tiny doses—sometimes just 10 milligrams can bring on symptoms. People with asthma face the highest risk, as sulphites can provoke sudden breathing problems. Food labels must carry sulphite warnings if a product contains more than 10 parts per million. This alert gives shoppers a fighting chance to steer clear.

More Than Just an Additive

Anyone who’s spent time in food production knows the balancing act behind additives. Potassium metabisulfite offers cheap insurance against unwanted microbes and loss of color in shelf-stable foods. During winemaking, it protects wines from spoilage without torching the flavors that took months to develop in barrel. It’s not some mysterious lab concoction—just a tool to keep products tasting fresh and free from mold or bacteria.

The trouble turns up when people lose control of dose. Homemade wine kits, for example, can leave room for error. Inconsistent mixing or adding too much powder can bump up the sulphite punch to uncomfortable levels. That’s less of an issue in regulated factories—those teams use precise measurement systems. Still, home experimenters need to stick to recipes and use reliable scales, especially if bottling for friends or family. Overuse can not only bring harsh flavors, but also cause headaches or worse.

Safer Practices for Everyone

Experience teaches that plenty of folks never read a label or know what E-numbers mean. Schools can help by giving kids hands-on lessons—checking the back of snack packs, talking about food sensitivity, or even visiting local food plants. People living with sulphite sensitivity should always check labels, ask about food prep at restaurants, and carry medicine if needed. Family or co-workers can keep a lookout too, turning a private struggle into a problem everyone solves together.

Food scientists keep testing alternatives, from rosemary extract to vitamin C, but nothing matches sulphites for reliability on a mass scale. Each new ingredient gets the same careful review as sulphites did. It’s not about scaring anyone away from modern food—it’s about making choices with open eyes, backed by clear facts.

Making Informed Choices

Over the years, I’ve seen how a simple question—“Is it safe?”—opens the door to bigger conversations about trust in food and science. A little knowledge goes a long way. Potassium metabisulfite doesn’t deserve panic, but it does call for respect, smart habits, and clear rules about how much lands in our food. The more we know, the better we eat.

How do you use potassium metabisulfite in winemaking?

Understanding Its Role in the Cellar

Making wine, especially grape wine, demands more than just patience and good fruit. Microbes, oxygen, and wild yeasts love a sugary grape must as much as any winemaker. That’s where potassium metabisulfite comes in. This white, crystalline powder releases sulfur dioxide (SO2) when dissolved in water or must. SO2 isn’t just some mysterious chemical—it’s one of the oldest and most trusted tools in wine cellars around the world.

Why Winemakers Trust Potassium Metabisulfite

SO2 does double duty. On one hand, it protects must and finished wine from wild yeasts, bacteria, and spoilage. On the other, it blocks oxygen, slowing the browning and staling that can turn vibrant juice into a tired, flat beverage. I’ve watched a fresh carboy of chardonnay left untreated for a week turn funky and nearly undrinkable, while a batch treated with SO2 stayed bright, fresh, and full of aroma.

Application at Crush

Crushed grapes wake up all sorts of wild yeast and bacteria living on skins and equipment. Hitting the must with potassium metabisulfite at this point does more than knock back these potential spoilers—it gives your chosen wine yeast a fighting chance to take over the fermentation. For starters, 50–75 mg per liter of must (about 1/4 teaspoon per 5 gallons for typical home batches) usually sets the stage right before pitching yeast. Overdosing won’t make the wine safer or cleaner; too much SO2 stuns your wine yeast and leaves off-flavors and rotten-egg notes that no one enjoys.

Monitoring SO2 Levels: More Than Guesswork

Accuracy matters with this chemical. Relying on rough measures is asking for trouble, so invest in SO2 test kits or titration drops. The right SO2 level depends on pH—lower pH (more acidic wine) needs less. Most professional cellars keep 20–50 free mg/L in white wines and 10–30 in reds. Small home batches can swing out of range if you guess, leading to either spoiled wine or one with a harsh chemical nose. If you’ve ever tasted a bottle that stings your nose or seems lifeless, either wild bugs or too much preservative probably had their way.

Safeguarding Wine Through Aging and Bottling

SO2 isn’t just for day one. As wine ages, oxygen sneaks in through airlocks and even corks. Topping up with potassium metabisulfite every couple of months, and right before bottling, locks in freshness. I add it primarily during rackings and check levels meticulously before moving wine to bottle. Too little and you risk months of effort fading fast. Too much, and you get that classic “burnt match” aroma that’s tough to shake.

Best Practices for Home Winemakers

Proper use of potassium metabisulfite isn’t complicated, just requires attention. Always dissolve it in a bit of water, never toss dry crystals into wine—they won’t distribute evenly, and that leads to pockets of overly high concentration. Keep a small scale in the winery and record every addition. Clean tools and sanitized carboys matter just as much as the right dose. Take the time to learn your wine’s pH, keep a logbook, and don’t cut corners on testing.

Respecting Both Tradition and Science

Great wine rewards careful handling. Potassium metabisulfite, used wisely and sparingly, acts as both shield and safeguard. It doesn’t fix bad grapes or sloppy cleaning, but it gives good raw material the shot at becoming something truly remarkable. Those who treat it as a crutch often end up battling the very problems they set out to solve. A deft touch, tight records, and regular monitoring keep both bugs and off-flavors at bay, letting the fruit do the talking in the glass.

What is the recommended dosage of potassium metabisulfite?

Understanding Its Role in Winemaking and Food Preservation

Potassium metabisulfite shows up in many wineries and homebrew setups. People know it as a go-to ingredient for preserving wine and preventing unwanted bacteria or wild yeast from turning a good batch sour. Winemakers rely on it because nothing ruins a vintage faster than oxidation or microbial spoilage. I’ve experienced first-hand how a forgotten dose left cloudy bottles and off-smells—lessons I won’t repeat.

The general advice in most wine circles points to 50–75 milligrams per liter (mg/L) for must sterilization before fermentation kicks off. That means people usually dissolve about one gram in a bit of water, then stir it into a 20-liter fermenter. After the initial fermentation, the story changes: topping up usually calls for 30–50 mg/L every racking, especially for white wines. Red wines handle smaller doses because their tannins and antioxidants help out.

Why These Amounts Make Sense

Let’s cut through the numbers and talk about why this amount matters. More isn’t better—overdosing can leave a sharp smell and taste that turns even the nicest Chardonnay into something people politely set aside. The World Health Organization pegs the acceptable daily intake of sulfite at 0.7 mg per kilogram of body weight. Sticking to that protects consumers, especially those sensitive to sulfites, who might experience headaches or asthma-like symptoms.

Sulfur dioxide, which potassium metabisulfite releases, binds with oxygen and cleans up microbes. This isn’t just theory; loads of studies point out its strong antimicrobial and antioxidant effects. Skipping this crucial step can turn weeks of hard work into an undrinkable mess, especially if natural wild yeasts or spoilage bacteria find their way into the fermenter.

Testing and Adjusting Dosage: Don’t Fly Blind

Over years of making cider and small-batch wine, I learned early mistakes stick. The “just eyeball it” approach didn’t work—my first five-gallon wine went flat with not enough protection. This taught me about test kits and pH meters. Acidity changes the effectiveness of potassium metabisulfite; more acid means less is needed. People with different water sources or fruit types sometimes need to test more. Test strips or digital titration kits help figure out what’s dissolved in the batch and avoid going over or under the mark.

Regulations and Labeling: Keeping Consumers Safe

Food safety watchdogs, especially in the US and EU, require labeling if sulfite content passes 10 mg/L. This matters because plenty of people want to know what goes into their glass. Producers can’t ignore these rules without risking fines and a bad name. Folks at home should pay attention too. Kids, pregnant women, or asthmatics can react poorly—there’s no easy fix after bottling if the dose goes too high.

Managing Dosage Responsibly

Paying attention to cleanliness, fruit ripeness, pH, and temperature means you can often use less potassium metabisulfite and get the same result. Fermenting in cool conditions with careful hygiene means less risk from bacteria, so there’s less need to add extra chemicals. This isn’t just about taste—it’s about protecting health, avoiding waste, and making something worth sharing.

Are there any side effects or health risks associated with potassium metabisulfite?

Why People Use It In Food and Drinks

Potassium metabisulfite shows up a lot in winemaking, beer brewing, and food preservation. People count on it to stop spoilage from bacteria and molds. Adding it to white wine, for example, keeps the flavor clean and extends the shelf life. You might not spot it on ingredient labels if it’s below certain levels, but it’s behind the scenes in countless products at the store.

Where Side Effects Begin

Sulfites like potassium metabisulfite don’t sit well with everyone. Some folks react after eating dried fruit, drinking certain wines, or tucking into canned foods. The reaction doesn’t stop at a sneeze or a mild itch. For people with asthma, exposure can bring on wheezing, chest tightness, or even a full-blown asthma attack. Research shows that between 3 and 10 percent of asthmatics are sensitive to sulfites, which isn’t a small group.

I’ve seen someone deal with sulfite sensitivity up close. At a family dinner, my aunt started coughing after a glass of chilled white wine. She started using her inhaler and looked genuinely scared until it passed. This kind of risk doesn’t always get enough attention, partly because labels are easy to gloss over. A simple dessert or a glass of lemonade from a mix can be enough to trigger symptoms if sulfites are hiding inside. People without asthma rarely notice a problem, but for those who react, it gets serious fast.

The Main Health Questions

The FDA recognizes potassium metabisulfite as generally safe, but there’s a ceiling to how much can safely go into food — about 0.01% for most cases in the U.S. Europe draws the line a little differently but shares the same spirit of caution. If you cross that threshold, the food starts to smell and taste bad, so it’s rare for legal products to blow past the limit. But the real-life challenge doesn’t always center on quantities. For sensitive people, even a small dose brings trouble.

Chronic exposure may do more than irritate a sensitive airway. Studies point to irritation in the throat, hives, headaches, and in some odd cases, stomach pain and nausea. In the wine world, “sulfite-free” wines get buzz for these reasons, though they aren’t entirely free of natural sulfites. Most folks never notice, even after years of sipping and snacking. The worry tends to crop up for people with a family history of allergies and people with severe asthma.

Ways Forward: Protecting Health Without Ditching Modern Convenience

Food labeling matters a lot. I learned to help my aunt check labels on store goods. Packaged foods in the U.S. listing more than 10 parts per million of sulfites must state it on the label, but it wouldn’t hurt to require that for all amounts. Restaurants and bars could share more details about sulfite content. Clear information puts control back in the hands of diners and shoppers.

Producers who crave fewer sulfites in recipes might try alternative preservatives. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and citric acid work well in many foods and don’t cause these reactions. Makers of small-batch wine and beer can experiment with handling, temperature, and packaging to reduce the need for chemical additives. Smaller players tend to move quicker on these changes, but big manufacturers can adopt gentler methods over time. People with severe sulfite allergies should have support from doctors and easy access to safe, comparable products. A bit of awareness and clear information go a long way toward avoiding another asthma scare at the dinner table.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium oxido-oxididosulfate |

| Other names |

Pyrosulfite Disulfurous acid, dipotassium salt Potassium pyrosulfite E224 |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˌtæsiəm ˌmɛtəˈbaɪsʌlfaɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium oxido(sulonato)sulfate |

| Other names |

Pyrosulfite Disulfurous acid, dipotassium salt Potassium pyrosulfite K2S2O5 |

| Pronunciation | /pəˌtæsiəm ˌmɛtəˈbaɪsʌlfaɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 16731-55-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3561332 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:61357 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1357 |

| ChemSpider | 14232 |

| DrugBank | DB14526 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.021.170 |

| EC Number | 231-673-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 778 |

| KEGG | C07392 |

| MeSH | D011096 |

| PubChem CID | 24415 |

| RTECS number | SY7550000 |

| UNII | 94H4R9AnNA |

| UN number | UN 1499 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4023497 |

| CAS Number | 16731-55-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3563781 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:61258 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1359 |

| ChemSpider | 14106 |

| DrugBank | DB14526 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b3f2da-5a98-48ba-9c8c-0c715f46b6d0 |

| EC Number | 224-167-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 19654 |

| KEGG | C18696 |

| MeSH | D010947 |

| PubChem CID | 24460 |

| RTECS number | TP2275000 |

| UNII | 0WNHG1K75S |

| UN number | UN 1490 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | K2S2O5 |

| Molar mass | 222.32 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Pungent, sulfur dioxide odor |

| Density | 2.34 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 65 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -3.1 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.15 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.410 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | K2S2O5 |

| Molar mass | 222.33 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Pungent, sulfur dioxide odor |

| Density | 2.34 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 65 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -3.1 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 7.0 (1 g/L, H₂O, 25 °C) |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb 6.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.470 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 165.8 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1047 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1451 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 137.6 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1046 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1369 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CQ01 |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Oxidizing, harmful if swallowed, causes skin and serious eye irritation, may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye damage. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-1 |

| Autoignition temperature | 220 °C (428 °F) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 2,500 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 2,330 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WN5600000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | IDHL: 3000 mg/m³ |

| Main hazards | Hazardous if swallowed, may cause respiratory irritation, causes severe skin burns and eye damage. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS05 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. H318: Causes serious eye damage. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-0-1 |

| Autoignition temperature | > 190°C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 2,500 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 2,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WS5600000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Potassium Metabisulfite: 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 5 mg/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 1500 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Potassium bisulfite Sodium metabisulfite Sulfur dioxide |

| Related compounds |

Potassium bisulfite Sodium metabisulfite Potassium sulfite Potassium sulfate |