Potassium Gluconate: A Closer Look at a Modern Essential

Historical Journey

Potassium gluconate has stories reaching back to the early efforts in mineral therapy, where doctors sought relief for patients struggling with low potassium. Before the age of supplements and precise diagnostics, potassium deficiency meant fatigue, cramps, and risk for more serious health consequences. Early chemists recognized that raw potassium salts did a number on the gut, so compounds with better absorption were needed. Gluconic acid, derived from glucose, met potassium’s need for a bioavailable partner. By the late 19th century, medical formulations included potassium gluconate, giving doctors a tool that balanced effectiveness with relative gentleness on the body. Through decades, the pharmaceutical industry kept refining production and purity, eventually meeting modern food and drug standards.

Product Snapshot

Walk down any pharmacy aisle and you’ll find potassium gluconate in tablets, powders, and sometimes liquid forms. The most common role: oral supplement to replenish potassium levels. Athletes, those on certain medications, or individuals fighting chronic illnesses often grab this product for its reliable potassium content. Outside of health, it finds a place in laboratory reagents and, in some cases, as a food additive, hitting a sweet spot between function, price, and tolerability.

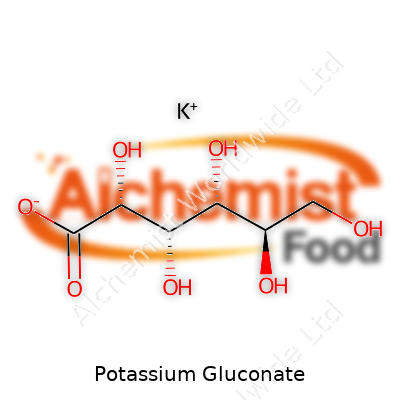

Physical and Chemical Traits

Potassium gluconate shows up as a fine, white to off-white powder. The taste leans to mildly salty and slightly bitter, though less offensive than raw potassium chloride. Water readily dissolves the powder, but alcohol shrugs it off. The molecular formula is C6H11KO7, with a molecular weight around 234 grams per mole. In the right storage—cool, dry, and away from light—it remains stable for long stretches. Once dissolved, though, it’s wise to use it soon, as solutions can invite bacterial growth if left out.

Technical Specs and Labeling

Regulations insist on clarity for nearly every pack or bottle. Potassium content, purity percentage, batch code, expiration date, and manufacturer traceability now define a credible label. Quality standards align with pharmacopeia requirements such as USP, BP, or EP standards, which set narrow boundaries for impurities, loss on drying, and heavy metal content. Most supplements will show potassium gluconate per dose and direct consumers not to exceed recommended amounts, tying into broader safety campaigns. Each label aims to guide consumers, but with supplementation there’s no room for guesswork—overdosing can cause real harm, so clear guidance remains critical.

Preparation Methods

Industrial synthesis relies on the reaction of potassium carbonate or potassium hydroxide with gluconic acid. Gluconic acid itself comes from the aerobic fermentation of glucose, often using strains of Aspergillus niger or similar microbes. Once mixed, neutralization yields a crude salt, typically purified through crystallization or other separation techniques. Manufacturers race to improve yields, cut costs, and minimize the traces of starting materials or byproducts. The final drying stage ensures the product doesn’t clump or degrade in storage, important for both large-scale operations and pharmacies slicing pills for individual doses.

Chemical Reactions and Modifications

Potassium gluconate stays relatively stable under neutral and basic conditions but starts to decompose under strong acids, breaking down into gluconic acid and potassium ions. Direct modification is rare in consumer products, though research circles explore its use as a precursor for potassium-based catalysts, buffering agents, or novel organic syntheses. Contact with oxidizing agents does not play well for this salt, and heat above decomposition temperatures releases fumes best avoided in a workplace. Under day-to-day conditions, this molecule stays firmly in its lane, delivering potassium where it’s needed without fuss.

Alternative Names

Step into a chemistry lab or medical library and you might hear potassium gluconate referred to as “gluconic acid potassium salt,” “monopotassium gluconate,” or even just “E577” (its European food additive code). Each name highlights a different community or regulatory scheme, but pharmacists, food scientists, and researchers all point to the same compound in the end.

Safety and Operations

Every factory or research lab handling potassium gluconate tracks safe handling guidelines. Standard operating procedures call for gloves and eye protection during processing and mixing, mainly to avoid mild irritation from dust. The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) doesn’t see major workplace hazards compared to many other industrial chemicals. Still, purity matters: contamination with other potassium salts or unreacted gluconic acid can bring safety problems, especially if dosing isn’t accurate. Food industry and supplement makers routinely audit their processes for cross-contamination and track every lot from raw powder to final bottle. Consumers should pay close attention to recommended doses, since excessive potassium intake leads to dangerous cardiac effects, especially for individuals with impaired kidney function.

Application Areas

Potassium gluconate snugly fits in supplements for athletes and people on diuretics, helping support nerve and muscle function when ordinary diets run short on potassium due to illness, stress, or food insecurity. Beyond individuals, the food industry uses it as a replacement for regular salt in low-sodium products, allowing processed foods to keep taste and shelf life while cutting sodium’s cardiovascular risks. In laboratories, this compound slides into cell culture work and as a buffer in biochemistry experiments. Water treatment processes sometimes use it to manage mineral balance. The mix of safety, solubility, and relatively mild taste gives potassium gluconate a secure future in both wellness and industry.

Research and Development Work

Academic and pharmaceutical researchers look for new ways to improve potassium delivery, absorption, and tolerance. Recent studies dig into how the gluconate ion affects absorption in the digestive tract compared to other common potassium salts. There’s real hope that smaller doses could offer better bioavailability when paired with strategic dietary changes or novel formulations. Minor advances in manufacturing are shaving costs and boosting yield with green chemistry and biotechnology, which reduces the environmental footprint—a rising concern as both pharmaceutical and food sectors pursue sustainability goals. Some labs investigate new uses, such as stabilizing agents in injectable drugs or trace mineral carriers in personalized nutrition regimens, showing that established compounds like potassium gluconate never stand still.

Toxicity and Health Findings

Potassium gluconate remains widely recognized for its safety when properly dosed, but as with any potassium compound, there’s a razor-thin line between helpful and harmful. Small studies on healthy adults show most people tolerate the recommended amounts very well, rarely seeing more than mild digestive upset. Cases of toxicity usually center on overdose—either from mistakenly high doses or from impaired renal function, which slows potassium excretion and can produce life-threatening symptoms like abnormal heart rhythms. Regulatory agencies, including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), set maximum daily intake recommendations that guide the supplement market. Long-term toxicity studies in animals have not flagged cancer risks or cumulative organ damage at sensible doses, but health practitioners stay wary for those on potassium-sparing medications or with kidney trouble. As the pandemic drove renewed interest in personal health and supplementation, public education campaigns stress the balance between correcting deficiency and risking toxicity.

What the Future Might Hold

Trends in nutrition and healthcare point toward even greater demand for potassium gluconate, as more people recognize the essential role of potassium and medical advice leans into preventive therapy. Innovation in supplement delivery and pharmacokinetic research could see microencapsulated forms hitting markets, promising fewer side effects and better absorption. Both pharmaceutical and food sectors will stay under pressure to clean up supply chains, improve traceability, and push for even tighter impurity limits in supplements and processed foods. New ventures may blend potassium gluconate with other functional minerals to support holistic health, backed by fresh clinical trials and consumer data. Growing calls for heart-healthy diets and reduced sodium intake keep potassium salts front and center for product developers. In coming years, continuous improvement in science, safety, and consumer understanding will shape how this long-standing, reliable compound finds its way into more homes and industries worldwide.

What is Potassium Gluconate used for?

Looking at Potassium Deficiency

Nobody talks much about potassium, but the body feels the shortage. Leg cramps, muscle weakness, even heart rhythm changes—these show up when potassium misses from the diet. Bread, fruits, and leafy greens provide plenty, though life gets busy or health makes things tricky. Potassium gluconate steps into this gap. One reason behind the push for this supplement is that certain medications, like diuretics for high blood pressure, drain potassium faster than you can replace it with a sandwich and a banana.

How Potassium Gluconate Helps

Some people think all supplements work the same way, but I learned that’s not true. Potassium gluconate offers a milder form of potassium. Hospitals and clinics use stronger versions for emergencies, but those can hit the stomach hard. Gluconate blends easier with water and skips that burning taste, so folks handling chronic low potassium can take their steady boost at home. It won’t fix the problem overnight, yet it gives a gentle nudge in the right direction. You see, the mineral keeps nerve signals and muscles firing smoothly. Without it, daily tasks feel tougher.

Who Uses Potassium Gluconate?

Doctors often recommend potassium gluconate for people living with high blood pressure, heart disease, or chronic kidney trouble. These groups face higher risk because their medicines or conditions can sap potassium quickly. Athletes sometimes turn to this mineral, hoping to stave off cramps after tough workouts, though for most, diet alone does the trick. An average adult eating a balanced plate rarely needs a pill, but if blood tests show the tank running low, supplements fill in the gap.

Safety: Keeping the Balance

There’s a catch to supplements. Too much potassium can turn dangerous, especially for people with weak kidneys. I’ve seen people assume more equals better, but that’s risky thinking. Signs like numbness, trouble breathing, or pounding heartbeat deserve quick medical help. Blood work plays a big part here. Most doctors check potassium levels before giving the green light. Over-the-counter versions contain smaller amounts than prescription pills for this reason. Many products top out at 99 milligrams per tablet—a drop compared to the daily amount from food.

Better Choices, Better Health

The easiest wins come from small moves: swap chips for baked potatoes, pick up a salad or grab an orange after a workout. These steps keep potassium steady and sidestep the confusion over pills and powders. Still, supplements like potassium gluconate give a vital option for those with extra challenges—older adults, anyone with certain digestive conditions, or people forced to avoid potassium-rich foods. That’s why pharmacies keep these tablets close at hand.

What Works in Practice

Potassium gluconate won’t cure medical problems all by itself. It fills a need, not a cure-all promise. Anyone thinking about adding it should ask a professional who knows their story. I’ve seen real benefits when people use it right and follow up as needed. No shortcuts—just one more way to keep things on track and avoid the pitfalls that life or illness can throw at us.

How should I take Potassium Gluconate and what is the recommended dosage?

What Potassium Gluconate Does

Potassium keeps nerves talking, muscles working, and the heart beating at a steady pace. Most folks picture bananas when thinking about getting enough of this mineral. But for some, supplements such as potassium gluconate fill the gap. Doctors use it for patients with low potassium, heart concerns, or who take certain medicines like diuretics that pull potassium out of the body.

Dosage: Not a One-Size-Fits-All

Determining the right amount comes down to individual need. The U.S. National Institutes of Health says adults need about 2,600-3,400 milligrams of potassium from diet each day. A potassium gluconate tablet usually contains only around 99 milligrams of elemental potassium—because too much at once can bother the stomach or even cause trouble for the heart. You won’t find massive doses over-the-counter for exactly that reason.

Most of the time, doctors tell people to take a pill once or twice daily. Sometimes more, sometimes less—it depends on lab results. I remember being cautioned by my own physician not to chase high doses on my own when I was on water pills after surgery. The risk of throwing off my whole electrolyte balance was real, and side effects like weakness and irregular heartbeat are nothing to play around with.

Tips for Safe Use

Potassium in high doses can hurt more than help. People often skip reading the label, thinking more means better results. Not so with this mineral. Swallow potassium gluconate tablets whole; breaking or crushing them delivers too much at once and can burn the throat or stomach. Drinking a full glass of water helps move it along and lowers the chance of stomach upset.

If taking other prescription medicines—such as ACE inhibitors for blood pressure or NSAIDs for arthritis—make sure to ask your doctor about interactions. Both can mess with how the body manages potassium. I once saw a colleague ignore these warnings. He ended up with dangerous potassium levels after mixing supplements and blood pressure pills.

Warning Signs and What to Watch For

Sometimes symptoms sneak up when potassium gets out of whack. Cramps, muscle weakness, numbness, or trouble breathing all deserve attention. In serious cases, very high potassium throws heart rhythm into chaos. Tests are quick and simple—a blood draw tells the story.

Skipping doses or doubling up by mistake happens more often than people think, especially with older relatives juggling many medicines. Keeping a daily log or using a pill box helps avoid mix-ups.

Eat Your Way to Healthy Potassium

Supplements help, but whole foods pack plenty of potassium and other nutrients. Beans, potatoes, leafy greens, and yogurt all fit the bill. Most people who eat balanced meals don’t need a supplement at all. For those with kidney issues, extra potassium can turn dangerous, so doctor advice is essential before starting anything new.

Solutions for Getting Dosage Right

Clear communication with a health provider makes a difference. Bringing up every supplement and medicine at checkups helps spot problems before they start. Pharmacists can also double-check for interactions. If lab tests suggest low levels, following the prescription exactly brings the safest results.

Potassium gluconate isn’t some everyday vitamin to pick up on a whim. Sticking to prescribed amounts, listening to your body, and staying honest with your medical team take the guesswork out of keeping potassium right where it should be.

Are there any side effects or risks associated with Potassium Gluconate?

Potassium Gluconate Isn’t Just Another Supplement

Lots of people grab potassium gluconate off pharmacy shelves believing it can “fix” low potassium or keep their hearts and muscles going strong. After all, potassium sits up there with sodium and calcium as one of our body’s most-wanted minerals. Doctors sometimes recommend it for folks with certain health problems or those taking medications that mess with potassium levels. It shows up in Google searches from folks trying to figure out fatigue, muscle cramps, and pounding heartbeats.

Risks—Because Too Much Potassium Spells Trouble

Taking extra potassium in the form of gluconate isn’t free of risk. There’s an important line between having enough potassium and having too much. The kidneys do the heavy lifting of keeping that balance. If they don’t work well—think older folks, folks with heart or kidney problems, or those on meds like ACE inhibitors—extra potassium can start to pile up in the blood. High potassium plays out in scary ways: muscle weakness, confusion, a heartbeat that flutters or stalls. If it builds up enough, the heart can stop working the way it should. According to the FDA, supplements should not deliver more than 99 mg of elemental potassium unless prescribed.

Everyday Side Effects Aren’t Invited, Either

Even at recommended doses, some people notice odd belly pains, nausea, or diarrhea. These side effects push some to quit before finishing a bottle. People with sensitive stomachs usually feel it worse. Crushing or breaking tablets instead of swallowing them whole ramps up the chance of stomach irritation. That’s why the directions always say: take this with a full glass of water, and never on an empty stomach.

Missing the Main Cause Leaves a Bigger Problem

Potassium isn’t the sort of mineral that's easily depleted unless something else is going on. Common causes of low potassium include certain diuretics, long bouts of vomiting, or conditions like Crohn’s disease. Masking those issues with more potassium isn’t a real solution. Low potassium sometimes means there’s a bigger health concern that needs a doctor’s attention—not just a change to your supplement routine.

Drug Interactions Join the List of Worries

Mixing potassium gluconate with other drugs spells even more trouble. ACE inhibitors for high blood pressure, some water pills, and drugs for organ transplant patients can tip potassium levels sky high. People who take these drugs don’t always realize that a store-bought supplement could send them to the ER. The U.S. National Institutes of Health warns about drug interactions and points out that anyone thinking about these supplements should check with a medical professional first.

Practical Steps Before Reaching for the Bottle

Focusing on a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole foods covers potassium needs for most people. Bananas, potatoes, beans, and spinach pack enough potassium to make most supplements unnecessary. Blood testing stays the gold standard for figuring out if potassium is low or dangerously high. For those with chronic conditions, partnering with a trusted doctor beats guessing based on symptoms or internet advice. Nobody knows your story the way you and your care team do.

Can Potassium Gluconate interact with other medications?

Looking Beyond the Supplement Label

Potassium gluconate often shows up in conversations when people want to boost their potassium without eating another banana. Many grab these supplements in hopes of steadying blood pressure, soothing cramped muscles, or filling some nutritional gap. Still, once it moves from the supplement shelf to our daily routine, every other medicine gets folded into the story. Ignoring that means missing out on what can keep you safe, especially if your health picture is complicated.

Common Interactions That Matter

Mix potassium gluconate with certain prescription drugs, and things change quickly. One set of medications that stands out is ACE inhibitors, such as lisinopril or enalapril. Doctors prescribe these for high blood pressure or heart troubles. These drugs tend to slow down the body’s natural way of flushing out potassium through urine. Add potassium supplements on top, and you run a risk of stacking up too much potassium. Excess potassium can make its mark on the heart, pushing up the possibility of rhythm problems or even irregular heartbeats.

Same goes for potassium-sparing diuretics. Spironolactone and triamterene help the body lose water but save potassium. This sounds like a good idea—until it isn’t. Combine these with potassium gluconate, and potassium levels might rise too high unless watched closely. If you’ve ever been told you have kidney disease or trouble, even a little extra potassium sneaks up on you because weak kidneys slow down its removal.

On the other hand, other diuretics—the so-called “water pills” like hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide—tend to drain potassium. Sometimes, this leads to a doctor writing up potassium gluconate to fill in what those pills wash away. It’s a balancing act, and it usually takes lab work to know if things are heading in the right direction.

Familiar Medications With Hidden Risks

Switch focus to pain relievers and you’ll find another concern. Some non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—like ibuprofen or naproxen—make kidneys work harder. This extra strain can lead to a buildup of potassium, especially if someone already takes a potassium supplement. For people with no kidney issues, a few days of NSAIDs may not matter. But for folks using these medications daily, or with existing kidney or heart problems, the story changes.

Even seemingly harmless antacids can sneak in. One common antacid, called “aluminum hydroxide,” sometimes makes it harder to absorb potassium from food and supplements. Unless your doctor or pharmacist walks you through potential effects, you might not see this twist coming.

Real-Life Lessons and Safer Paths

Speaking with a pharmacist can reshape your understanding. Their advice is built from seeing what happens when one prescription meets another or when supplements creep in. My own brush with high potassium came after I started a new medication for my blood pressure and didn’t realize my multivitamin had extra potassium. Bloodwork caught it before my heart felt any consequences. That taught me to run supplement plans by someone with the facts.

Checking with a healthcare provider offers more than a stamp of approval. They answer the questions you didn’t know to ask. Lab results can measure potassium and signal trouble before symptoms start. If your health needs include multiple prescriptions, routine blood tests aren’t just paperwork—they are real protection.

Keeping a list of every supplement and medication helps both you and your doctor keep pace with your health goals. Building trust with those who manage your care turns what can feel like mystery into something straightforward: if in doubt, just ask.

Is Potassium Gluconate safe for pregnant or breastfeeding women?

Looking at Potassium Gluconate in Everyday Life

These days, many women flip over supplement bottles, unsure if ingredients like potassium gluconate will help or hurt. Moms and moms-to-be already work hard enough to balance energy, health, and the happiness of their growing families. Sorting through advice, old wives’ tales, and scientific jargon can make decisions about supplements confusing. Potassium remains essential for nerve function, muscle contraction, and keeping electrolytes in check. Women need it every single day, but pregnancy and breastfeeding throw unpredictable twists into the body’s needs.

What Potassium Gluconate Does Inside the Body

The body uses potassium to support heartbeat, keep blood pressure steady, and help muscles—including the uterus—work smoothly. Low potassium risks go up if morning sickness leads to vomiting, or if preferences and cravings make eating a balanced meal challenging. Some prenatal vitamins skimp on potassium altogether, so it’s no surprise that women feel tempted to reach for a potassium pill at the pharmacy.

Is It Safe During Pregnancy?

Feeling run-down, having muscle cramps, or experiencing heart palpitations while pregnant sometimes signals a potassium imbalance. Doctors measure potassium using standard blood tests, so guessing isn’t smart here. Pregnant women who lack enough potassium because of diet, intense vomiting, or certain meds occasionally need supplements. But too much potassium can harm both mother and baby. Extra potassium, if not monitored, pushes blood levels over safe limits and strains the heart or kidneys.

No supplement, including potassium gluconate, replaces a foundation of colorful, potassium-rich foods like bananas, avocados, beans, and spinach. Most pregnancies do not require potassium supplements, and manufacturers make potassium gluconate for people who cannot meet needs with food or have physician-identified low potassium. The FDA limits over-the-counter potassium to 99 milligrams per pill for a reason. Higher doses belong to prescription territory only.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists points out that a healthy pregnancy usually covers potassium needs through food. If concerns arise, health care providers determine supplementation based on blood results, health histories, and safety for both mother and baby. No mom should self-prescribe potassium gluconate just because fatigue feels overwhelming.

What About Breastfeeding?

Breastfeeding draws on a mother’s nutrient stores, and potassium stays important for milk production and supporting a baby’s developing muscles and nerves. The good news: breast milk supplies enough potassium for infants when mothers eat well. Supplements should come into play only if a real deficiency exists, shown in lab results or noticeable health issues—and only under a physician’s eye. Healthy kidneys easily excrete extra potassium from foods, but not everyone processes supplements as safely.

Sorting Fact from Fiction and Making Safe Choices

Marketing campaigns can make it sound like everyone could use a little more of this mineral, but context matters. Women with kidney disease, heart conditions, or certain hormone problems see much higher risks from high-potassium supplements. Pregnant and breastfeeding moms should talk openly with health professionals about their symptoms and daily diet instead of guessing and reaching for supplements at random. Most of the time, preparing meals with a range of fruits and vegetables covers daily potassium needs far better than anything in a bottle.

Listening to the body and the doctor, not internet trends or supplement hype, remains the best way forward during these important years. With a personalized approach, mothers can stay confident about giving both themselves and their newborns a strong, healthy start.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium (2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate |

| Other names |

Potassium D-gluconate Gluconic acid, potassium salt E577 |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˈtæsiəm ˈɡluːkoʊneɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Potassium 2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate |

| Other names |

Potassium D-gluconate Potassium salt of gluconic acid |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˈtæsiəm ˈɡluːkoʊneɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 299-27-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1720830 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75233 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201564 |

| ChemSpider | 15424 |

| DrugBank | DB01397 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.011.114 |

| EC Number | 209-567-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | 75473 |

| KEGG | C00748 |

| MeSH | D017697 |

| PubChem CID | 23682522 |

| RTECS number | AR8750000 |

| UNII | FWH9G7RBQ5 |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CAS Number | 299-27-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1720479 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:62605 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201600 |

| ChemSpider | 16214513 |

| DrugBank | DB01844 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03cfa5c4-2c52-4d0b-a951-cfd8725bab24 |

| EC Number | 209-506-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 5748 |

| KEGG | C00745 |

| MeSH | D019340 |

| PubChem CID | 23668168 |

| RTECS number | GN4825000 |

| UNII | CPD4NFA903 |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8020297 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H11KO7 |

| Molar mass | 234.25 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.8 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble in water |

| log P | -3.3 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 4.60 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -51.2 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.49 |

| Dipole moment | 1.7 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H11KO7 |

| Molar mass | 234.25 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.8 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -3.36 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 1.8 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 0.36 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.54 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 1.82 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 206.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1616.6 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3774 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 253.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1567.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3853 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory tract irritation; May cause eye and skin irritation |

| GHS labelling | GHS labelling: "Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Store in a well-ventilated place. Keep container tightly closed. Wash hands thoroughly after handling. Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 6060 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 10.38 g/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | Not Established |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 1.5 mg(K)/kg bw |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H315, H319, H335 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use with adequate ventilation. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 6060 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 10.38 g/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | RN6303 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2 mg(K)/m³ |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Gluconic acid Calcium gluconate Sodium gluconate Iron(II) gluconate Magnesium gluconate |

| Related compounds |

Gluconic acid Sodium gluconate Calcium gluconate Magnesium gluconate Zinc gluconate Iron(II) gluconate Copper gluconate |