Potassium Ferrocyanide: A Close Look at Its Role, Risks, and Future

Historical Development

Potassium ferrocyanide came into the industrial spotlight centuries ago, back in the 18th century. Early chemists stumbled upon this compound in the course of searching for better pigments, and before long, it earned a reputation for making Prussian Blue, a pigment known for its intense color and durability. Factories across Europe began working with it, giving textile dye houses and artists a new palette to work with. Over time, the chemical found new life, branching into more practical uses that stayed long after the excitement over Prussian Blue faded from the headlines.

Product Overview

Potassium ferrocyanide goes by many names, like yellow prussiate of potash or E536 when added to table salt. It doesn’t spark much reaction until you see how widely it appears in food processing, photography, metal treatment, and even in laboratories. One bag of this pale yellow salt, tucked away in a storage cabinet, might serve dozens of industries. It runs like a quiet thread through all sorts of workflows, some mundane and some surprisingly high-tech.

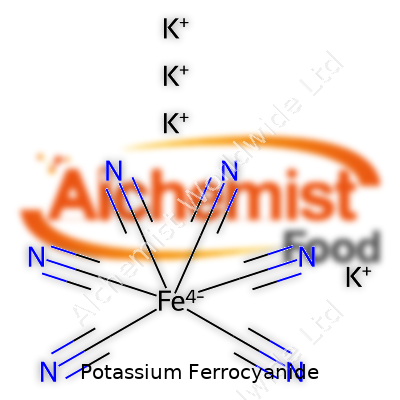

Physical & Chemical Properties

At room temperature, potassium ferrocyanide looks pretty unassuming—yellow crystals or granules, no strong smell, no fuss. Its ability to dissolve in water stands out. The molecular structure, K4[Fe(CN)6], keeps iron snug inside a cage of cyanide ions, which stops it from being as toxic as its relatives, like potassium cyanide. Still, the word "cyanide" spooks folks, and with good reason, though this molecule doesn’t break open easily under normal handling. Once dissolved, it turns laboratory solutions a mild yellow tint, a clue some might overlook unless they know their chemistry.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers label potassium ferrocyanide with clear technical specs to limit guesswork. Purity hovers around 99 percent for food-grade or lab-grade material. The material stays stable if kept sealed away from acids and moisture. Labels spell out basic safety directions, and strict rules shape the size, graininess, and even packaging types, especially for additives or materials destined for food production. This attention to detail isn’t about creating paperwork—it directly shapes worker safety and product performance.

Preparation Method

Chemists make potassium ferrocyanide by reacting ferrous salts (from iron) with potassium cyanide. Sometimes, leftover cyanides from coal processing or metallurgy set the process rolling. The resulting solution crystallizes out, and those solid yellow prismatic crystals get dried and processed, ready for shipping. Industrial operators handle volatile intermediate steps, using ventilation, sealed pipes, and safety monitors to tackle hazards before they reach the packaged product.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Though potassium ferrocyanide behaves gently around most bases and salts, things change fast in acidic conditions. A strong acid can break the iron-cyanide bonds to release hydrogen cyanide gas, a known poison. Chemists also use potassium ferrocyanide in complex reactions, from making pigments or metal salts to acting as a mild reducing agent. In water treatment, for example, it helps trap heavy metals, forming insoluble precipitates that settle out of solution. While not flashy, these reactions provide the foundation for dozens of practical tasks that seem simple only because the chemistry behind them works so well.

Synonyms & Product Names

People have given potassium ferrocyanide all sorts of handles over the years. Besides yellow prussiate of potash, names like E536 or ferrocyanate (when used as an anti-caking agent) turn up on ingredient lists. Chemists know what these code names hide, but regular folks might not realize the same chemical in table salt dust might be called something else if it shows up in an industrial tank farm down the road. This complexity confuses policy makers and average consumers alike, adding another wrinkle to safe handling.

Safety & Operational Standards

Strict rules guide use and storage, especially since the dangers come not from potassium ferrocyanide alone, but from what it could become under the wrong conditions. Anyone who’s spent time in a chemistry lab or food processing plant recognizes the yellow hazard diamond and warnings about acids stiffly posted on storage cabinets. Material Safety Data Sheets call for gloves and goggles, careful labeling, and special ventilation for large-volume operations. Teams drill for spills and accidental releases, not because the compound’s everyday form acts up easily, but because cutting corners can turn things dangerous in a hurry.

Application Area

Salt manufacturers use potassium ferrocyanide as an anti-caking agent, keeping grains loose and sprinkle-ready in supermarkets everywhere. Water treatment plants turn to it to bind with heavy metals, pulling toxins out of the water stream—an approach powering clean-up at everything from factories to drinking water plants. Labs rely on its stable chemistry for blood tests, pigment synthesis, and even teaching the basics of complex ion chemistry. During my time in a water testing lab, I watched technicians add potassium ferrocyanide to tricky samples, amazed at how one scoop can settle out nickel or copper, leaving clearer water than before. In the world of steel hardening, it shapes case-hardened surfaces. Photographers in the film era counted on it for specialized toning formulas and cyanotypes—those striking blue prints that still catch the eye of artists and historians alike.

Research & Development

Academic groups and industry labs still find new ways to use potassium ferrocyanide, exploring its potential as a remedy for heavy metal poisoning and as a catalyst for green chemistry processes with less waste. Some recent papers discuss tweaking the molecule to build new frameworks for battery technology or to act as building blocks for molecular cages in targeted drug delivery. Nothing sits still for long in a research environment; what looked ordinary last decade could anchor entirely new products or treatments tomorrow, depending on funding and collective curiosity.

Toxicity Research

Most toxicity studies focus on the cyanide part, but with potassium ferrocyanide, animal tests and human studies point to very low toxicity, provided it stays out of acidic or high-heat conditions. The body doesn’t break apart the molecule under normal circumstances, so the risk of cyanide poisoning remains small. Food safety agencies have set clear thresholds for how much gets added to salt and processed foods, based on years of animal testing. Environmental watchdogs, though, keep a sharp eye on discharge from industrial plants, pressing for low limits on any ferrocyanides entering waterways. From conversations with environmental consultants, I’ve learned regulators stay on higher alert in places where acidic waste might meet ferrocyanide runoff—for good reason, as this could shift the balance and create toxic releases.

Future Prospects

Potassium ferrocyanide sits at a crossroads right now: tried and tested, yet ripe for fresh ideas. Food processing isn’t going away, and neither is the need for safe, efficient anti-caking solutions. Clean water efforts place greater demand on heavy metal treatment, urging both established and small-scale municipal plants to look beyond basic old-school chemistry for more sustainable answers. Advanced manufacturing pushes for purer compounds as battery demands rise, from electric cars to renewables, and potassium ferrocyanide increasingly lands on researcher short lists as a stable backbone for new compounds. Policy trends point toward stricter environmental controls, higher transparency in food and water additives, and a push to engineer alternatives in case emerging risks demand a switch. As the chemical landscape shifts, companies, regulators, and the public stand to benefit if this old stalwart gets a second look through the lens of health, efficiency, and environmental care.

What are the common uses of Potassium Ferrocyanide?

A Colorful Role in Food Production

Potassium ferrocyanide sometimes gets a suspicious glance because of its chemical name, yet this yellow crystal has a long history in food. Some table salt producers add a pinch to prevent caking. Salt clumps are a nuisance, so using potassium ferrocyanide helps keep the grains flowing smoothly. European food safety authorities have taken a hard look at it and set intake limits, but the levels in salt stay far below those cut-offs. In the cheese world, making Roquefort and other blue cheeses involves complicated reactions. Here, potassium ferrocyanide comes in handy, keeping metals from causing off-flavors or colors.

Refining Sugar: Keeping Things Clear

Raw sugar is anything but pristine. It contains bits of plant, metals, and other impurities. Sugar refiners rely on potassium ferrocyanide’s ability to snatch up stray metal ions like iron. By pulling iron out of the raw mixture, refiners get a white, pure end product. This keeps the food looking inviting and tasting as expected. Without it, sugar would show hints of yellow or even rusty tones, which most folks would rather not see in their morning coffee.

Metallurgy and Printing: More Than Meets the Eye

People who work with metals know that surface treatment often calls for chemicals that can manage iron and steel. Potassium ferrocyanide steps into this process, sometimes helping to reveal flaws in steel during quality checks. In the dye and pigment industry, the famous “Prussian Blue” pigment comes from a reaction with potassium ferrocyanide. Artists have used Prussian Blue for centuries, and printmakers have depended on it for blueprints and cyanotypes. It’s behind the scenes in creating everything from engineering drawings to works of art.

Water Treatment Solutions

Clean drinking water should always be a priority. Water treatment plants face challenges with heavy metals. Some use potassium ferrocyanide to help trap copper and iron, making them easier to filter out. Getting rid of excess metals is not just about taste or color—regulations govern allowable levels to protect public health. By using potassium ferrocyanide in a controlled way, plants meet those benchmarks and deliver safe water to taps. Each step has to follow strict monitoring and testing because mistakes can impact people’s health.

Safety and Perception: Clearing the Air

Potassium ferrocyanide sounds dangerous, and concerns usually stem from the word “cyanide”. Real-life use proves otherwise. Inside the chemical structure, cyanide ions are locked so tightly that they don’t break free during everyday applications. Decades of food science research and strict oversight from agencies like the FAO and WHO have ensured that the levels used in food or water treatment stay well within safety margins. Having open communication between producers and consumers fosters trust, and transparent labeling allows people to make informed choices.

Looking Forward: Responsible Use

Modern industry keeps an eye on environmental impact. Technologies evolve and regulators set higher standards for chemical residues. Potassium ferrocyanide continues to fill a practical role, but alternatives and improvements show up with advances in green chemistry. Companies focus on minimizing leftover chemicals in finished products and recycling as much of the processing chemicals as possible. Investments in better filtration and process control lead to cleaner outcomes, so using chemicals like potassium ferrocyanide remains part of the solution rather than the problem.

Is Potassium Ferrocyanide safe for use in food products?

Understanding Potassium Ferrocyanide

The name “Potassium Ferrocyanide” can grab attention and spark questions—especially when found on food labels. At first glance, the term looks technical and even a little intimidating. Many people see “cyanide” and feel wary. That unease is understandable, so digging into what this compound is and its place in our food supply makes sense.

What It Does in Food

Potassium ferrocyanide helps keep table salt free-flowing. In the food industry, clumps in salt packs cause hassles for both factories and home cooks. By adding this compound in very small amounts, salt producers prevent moisture from causing salt crystals to stick together. The European Union, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and several other authorities recognize potassium ferrocyanide as safe when used within strict prescribed limits.

Should Consumers Be Worried?

The word “cyanide” brings to mind toxic substances, and that’s not lost on folks flipping over a salt container to read the ingredients. But potassium ferrocyanide is not the kind of cyanide that kills. The molecule is stable. It doesn’t break apart and release free cyanide under normal conditions found in the body or kitchen. In fact, you’d need to heat potassium ferrocyanide above 400 degrees Celsius—much hotter than even commercial kitchen ovens reach—for it to decompose into anything dangerous.

Safety assessments from agencies like the World Health Organization and the European Food Safety Authority back this up. They’ve looked at toxicology data, metabolic studies, and observations from decades of food use. The acceptable daily intake (ADI) established leaves a generous safety margin. Most people’s real exposure through regular salt use stays well below this threshold.

Trust in the Testing

Questions about food additives hit home for me because my family watches ingredients closely due to allergies. What matters most is transparency, clear labeling, and good science. Food safety agencies perform continuous reviews. If new evidence came up showing actual harm, these bodies would act fast—either by lowering allowed limits or pulling the ingredient from the market. That's how it works for things like food dyes, preservatives, and, yes, anti-caking agents.

That said, labels should signal clearly what people are eating. Shoppers deserve to make informed choices, including those who want to avoid even very small amounts of any additive. Food safety regulations are not perfect, but they do offer a system where new research leads to rapid change.

Room for Better Approaches

Many people ask for cleaner ingredient lists. Some consumers want salt without anything extra. Companies have started responding with “additive-free” or “sea salt” alternatives, which use mechanical drying or packaging tweaks instead of chemical help. For people with health conditions or high salt sensitivity, these options add peace of mind.

Food research continues. Teams in universities and private labs always look for replacements that might ease public concerns—using more natural or less chemically complex ingredients whenever possible. It's slow going, but progress keeps pushing forward.

Final Thoughts

Potassium ferrocyanide, at the low levels used for anti-caking, passes the test for safety based on current, high-quality evidence. The strict controls and constant oversight mean genuine risks don’t slip through the cracks easily. Still, demanding better, simpler foods remains a healthy way for people to steer the marketplace—and themselves—toward choices that feel right.

What are the storage and handling precautions for Potassium Ferrocyanide?

Getting Familiar With Potassium Ferrocyanide

Potassium ferrocyanide is common in food production, lab work, and even photography. Despite its name, the word “cyanide” doesn’t mean it’s highly toxic on its own. But like any chemical, it demands some respect—especially in how it's handled and stored. People tend to ignore this compound, but that's where problems start.

Storing Potassium Ferrocyanide Safely

Good storage makes a world of difference with chemicals, and potassium ferrocyanide stands as no exception. Store it in a cool, dry place. Humidity invites trouble. Dampness can break down the chemical over time, and nobody wants to deal with clumpy powder or chemical changes that could affect its use. Closed containers keep out moisture and help prevent spills that are tough to clean and waste money.

Keep it away from acids. That’s not just a textbook rule. If potassium ferrocyanide comes in contact with acids, it releases hydrogen cyanide, and that’s a genuinely dangerous situation. Label shelves clearly and keep acids on a separate rack so there's never room for mix-ups, especially in a busy workspace.

Handling: Slow and Steady

On the handling side, treating the material with care goes a long way. Gloves protect your hands, even if the powder hasn’t spilled. Goggles block accidental splashes and dust. Dust seems harmless, but small inhaled particles are tough to avoid once they’re in the air. Even if the risk of acute toxicity is low, long-term exposure never does your body any favors.

Spills rarely make a dramatic entrance, but even a small one can linger. Clean them up using a damp cloth and toss used gear into designated hazardous waste bins. Skipping proper cleanup can leave behind residue, which sometimes interacts with other chemicals in ways you might not expect.

Why Small Precautions Matter

Potassium ferrocyanide is used in table salt to prevent caking, in winemaking, and in metallurgy. You’d think a food additive would suggest total safety, but accidents happen because of shortcuts and overconfidence. CNN reported not too long ago about a food facility where improper storage allowed moisture to get into supplies, leading to both product loss and workplace complaints. That kind of mistake strains trust and drains budgets.

With about 10,000 chemical exposures reported to U.S. poison control centers every year, most come down to simple mistakes like bad labeling, mixing incompatible chemicals, or a lack of basic training. Skipping steps for convenience never pays off. In my own lab days, rushing cleanup once cost us a costly equipment swap and several hours lost because a leaky cap dripped ferrocyanide onto a bench, which later was used for a completely different project. People forget how much one missed detail can shift everything off track.

Paths Forward: Training and Real Accountability

Rules aren't enough by themselves. Training sessions that feel routine lose everyone’s attention quickly. Practical, hands-on demonstrations help more. Pair new staff with experienced folks until the routine feels natural. Keep chemical inventories current and encourage everyone to point out issues before they turn into real dangers. Regular peer reviews for chemical storage aren’t just busywork—they force a second set of eyes on habits that get sloppy over time.

Storage and handling mistakes can be fixed by keeping your workspace organized, taking personal precautions, and speaking up about any concerns. With the right daily habits, potassium ferrocyanide is just another tool, not an accident waiting to happen. That’s what experience—and plenty of spilled salt—has shown me.

How is Potassium Ferrocyanide different from other cyanide compounds?

Getting Past the Scary Name

You hear “cyanide” and a wave of worry goes through the room. Cyanide carries an ugly reputation, thanks to its role in some notorious crimes and accidents. So people react with suspicion whenever they see “potassium ferrocyanide” on packaging or ingredient lists. I used to share that knee-jerk fear, especially after stories about cyanide poisoning. It took time and research to shake loose from those assumptions and figure out what sets potassium ferrocyanide apart.

Not All Cyanides Are Alike

Here's a basic fact: Potassium ferrocyanide doesn’t behave like the “bad” cyanides used in poisons. Its chemical structure locks away the dangerous cyanide part. Unlike potassium cyanide or sodium cyanide—both notorious for releasing deadly hydrogen cyanide gas—potassium ferrocyanide hangs onto its cyanide tightly. This stability means it doesn’t let go of cyanide easily. Chemical textbooks call it a coordination complex. That sounds dry, but it’s crucial for food safety.

Where It Shows Up

Food producers rely on potassium ferrocyanide to keep things clump-free. You might see it on table salt containers, tagged as E536. The amount is tiny. Food regulations in Europe and America set strict caps, and testing shows safety margins are wide. I learned this the hard way during a stint at a food company—people are always suspicious of anything with “cyanide” in the name, and it took more than one lab test to convince a roomful of managers.

Its use extends to the chemical industry, too. Metal workers prefer it for use in blueprints and as a stabilizer in pigment production. Here again, safety is built into the molecule: breaking it apart and getting dangerous hydrogen cyanide gas out of it requires harsh treatment—far more than you’d ever find in a kitchen, warehouse, or factory.

Fears and Facts

Most of the panic comes from confusion. Potassium cyanide—a different compound—is used in mining and has a deadly reputation. News stories around mining accidents or old murder mysteries spread old fears. The truth is, calling potassium ferrocyanide dangerous just because of its name ignores the tight hold its chemical structure has on free cyanide. Analyses run by regulatory agencies like the EFSA and FDA show that residual cyanide in foods with added potassium ferrocyanide falls so far below harm levels, the risk to people is negligible.

Solutions: Open Information, Not Just Chemistry Lessons

People want clear information, not jargon. My own encounters with food safety debates remind me over and over: trust comes from clear talk and independent proof. Food labels should explain why these anti-caking agents are used and point out their long record of safe handling. Chemists and regulators need to be accessible, giving the public straightforward evidence instead of hiding behind technical language. That goes for food safety and workplace rules alike.

Potassium ferrocyanide’s science separates fear from real risk. The answer isn’t to get rid of useful compounds but to back up their use with facts, transparency, and constant safety checks. My experience shows that calm, honest conversation wins out over scary names—every single time.

What is the chemical formula and structure of Potassium Ferrocyanide?

Breaking Down the Formula

Potassium ferrocyanide has the chemical formula K4[Fe(CN)6]. In plain terms, this means a single molecule carries four potassium ions, one iron atom, and six cyanide groups all held in a specific arrangement. The iron atom sits in the center, surrounded by those six cyanide ions, producing a stable coordination complex. In high school chemistry, this kind of arrangement fascinated me; seeing how atoms lock together, forming a structure that’s surprisingly tough, taught me a lot about chemical bonds.

The Structure Reveals a Lot

This yellow crystalline compound takes shape as a coordination complex. Iron, with a +2 charge, lies at the heart surrounded by six cyanide ligands. The four potassium ions keep everything balanced and carry the molecular charge. If you’ve ever mixed iron salts with potassium ferrocyanide in a lab and seen Prussian blue form, you’ve watched chemistry in action—a vivid color switch revealing those hidden structural relationships.

Practical Reasons to Know Potassium Ferrocyanide

Food safety organizations have a close eye on additives like potassium ferrocyanide. This compound often turns up in table salt or in the winemaking process, working as an anticaking agent. It keeps clumping at bay better than a paper packet ever could, and it does the job in unbelievably tiny amounts. Regulators in the European Union, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and other agencies permit trace levels, showing the trust in scientific studies into its risk profile. I learned early in my chemistry studies that most fears about “cyanide” in the name don’t hold up—the bonded form in potassium ferrocyanide keeps the otherwise dangerous cyanide ion locked up tight.

Understanding the molecular structure gives a window into its safety. Potassium ferrocyanide simply doesn’t break down under normal food storage or digestion, so the cyanide ions don’t just roam free. Peer-reviewed toxicology research, including detailed studies cited by the World Health Organization, backs up this position. Of course, in extreme conditions—strong acids or high heat—the story changes, but those cases rarely crop up in daily life or manufacturing settings.

Solutions and Responsibility

We all depend on rigorous oversight. Chemists, regulators, and manufacturers have to keep close track of how potassium ferrocyanide is used and monitored. Batch testing, supply chain checks, and food safety labeling don’t just protect companies; they keep us all safer. Equipment that handles large amounts in industrial settings must have the right fail-safes to avoid unintended reactions. Open communication from brands about their ingredients supports public understanding and trust.

In classrooms, talking about compounds like potassium ferrocyanide helps break down fear of chemical names and encourages a more nuanced view of what enters our lives. Facts and structure keep the conversation grounded—no need for panic, but every reason to respect the lessons of chemistry.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium hexacyanidoferrate(II) |

| Other names |

Yellow prussiate of potash Dipotassium hexacyanoferrate(II) Potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) E536 |

| Pronunciation | /pəˌtæsiəm ˌfɛroʊsaɪˈænaɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium hexacyanidoferrate(II) |

| Other names |

Yellow Prussiate of Potash Tripotassium hexacyanoferrate(II) Tripotassium ferrocyanide |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˌtæsiəm ˌfɛroʊˈsaɪənaɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 14459-95-1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | _3d:potassium ferrocyanide, id: K4[Fe(CN)6], model: JSmol, string: {2K+.Fe2+.6C#N-} |

| Beilstein Reference | 3564980 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:48807 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL135873 |

| ChemSpider | 5213 |

| DrugBank | DB13904 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 13-155-048-068 |

| EC Number | 206-122-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gm:1521 |

| KEGG | C18602 |

| MeSH | D010915 |

| PubChem CID | 10211 |

| RTECS number | SS1400000 |

| UNII | Q21MN73H8F |

| UN number | UN3076 |

| CAS Number | 14459-95-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3569229 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:48719 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1352 |

| ChemSpider | 52644 |

| DrugBank | DB14035 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 03-2119475601-41-0000 |

| EC Number | 206-122-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: **15778** |

| KEGG | C18618 |

| MeSH | D011096 |

| PubChem CID | 6093208 |

| RTECS number | SS8050000 |

| UNII | 3M60G0M3XW |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | K4[Fe(CN)6] |

| Molar mass | 368.35 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 1.85 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 27.5 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -4.6 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.0 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Paramagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.409 |

| Viscosity | Low viscosity |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | K4[Fe(CN)6] |

| Molar mass | 368.35 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 1.85 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 27.5 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -4.3 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.36 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Paramagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.682 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 333.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1191 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 333.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1181.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V03AB33 |

| ATC code | V03AB33 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed; may cause irritation to skin, eyes, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "H319 Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | NFPA 704: 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 790°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 6400 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 6400 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SY8650000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | REL (Recommended): 1 mg/m³ |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. May cause irritation to skin, eyes, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319, P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 6400 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 6400 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SN3075000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Potassium Ferrocyanide: "No OSHA PEL established |

| REL (Recommended) | REL (Recommended Exposure Limit): 1 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Potassium ferricyanide Sodium ferrocyanide Calcium ferrocyanide Ammonium ferrocyanide Iron(II) cyanide Prussian blue |

| Related compounds |

Potassium ferricyanide Sodium ferrocyanide Calcium ferrocyanide Ammonium ferrocyanide |