Potassium Citrate: History, Properties, and the Road Ahead

Historical Development

Potassium citrate traces its roots back to the early days of organic chemistry, well before the periodic table took its modern shape. Chemists first identified the versatility of citrates in treating medical conditions linked to diet and metabolism. Early pharmacists prescribed potassium citrate to offset acidity in urine, aiming to manage kidney stone formation even when doctors lacked our current understanding of biochemistry. Over time, with advances in synthetic processes, production expanded beyond pharmaceutical use. By the mid-20th century, potassium citrate found homes in food preservation, beverage production, and technical fields. The steady increase in health awareness and scientific interest in diet spurred the demand for well-characterized, high-quality potassium citrate, driving refinements in its manufacturing and regulatory standards.

Product Overview

Potassium citrate appears as a white, crystalline powder or small, transparent granules. Manufacturers deliver it with a neutral or slightly tart taste, which makes it suitable for blending with food and pharmaceuticals. Formulators have turned to potassium citrate to provide potassium ions in supplement mixes and as a buffering agent where acidity requires careful control—an issue that matters whether for keeping beverages shelf-stable or supporting renal health. You’ll run into potassium citrate on ingredient labels for everything from lemon-lime sodas to prescription tablets, attesting to its role as a dependable salt in both daily routines and specialized environments.

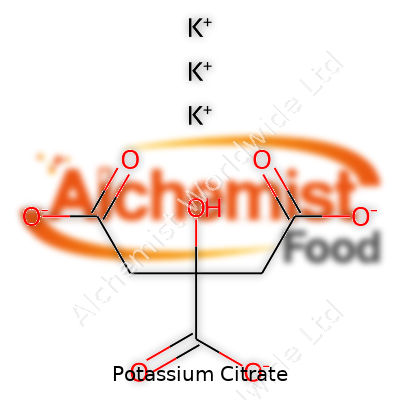

Physical & Chemical Properties

At room temperature, potassium citrate stands as a stable, crystalline solid, highly soluble in water yet insoluble in alcohol. Its molecular formula, C6H5K3O7, encodes three potassium ions per citrate molecule, giving it a lightweight, ionic character. Because it melts only at rather high temperatures and decomposes when pushed further, potassium citrate demands solid containers away from fire or strong acids. The odorless, non-volatile powder doesn’t attract moisture from the air in the way some salts do, making storage and handling less troublesome in production plants or pharmacies.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Regulatory frameworks such as the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and European Pharmacopoeia (EP) set the bar for potassium citrate purity and impurity limits. These guidelines call for at least 99% active compound, with stringent caps on heavy metals, loss on drying, and contaminants. Packaging often includes food-grade or pharmaceutical-grade designations, batch number, expiration date, and supplier information. In food applications, potassium citrate appears under the additive code E332, which flags it as an acidity regulator and stabilizer. Labeling also demands clear directions for storage—mainly, keep it dry and at room temperature—to help ensure solid performance right up to its labeled use-by date.

Preparation Method

To make potassium citrate, producers react pure citric acid with potassium carbonate or potassium bicarbonate, both commonly available industrial salts. The reaction yields potassium citrate and carbon dioxide gas—a relatively straightforward setup in a stainless steel reactor tank. As carbon dioxide escapes, the operator stirs and heats the solution just enough to speed up the process without degrading the product. The clear solution crystallizes on cooling, with the resulting crystals collected, washed, and dried before packaging. Plants invest effort in purification and careful filtering to secure product that meets pharmaceutical standards, free of trace acids, insoluble residues, or any dust from previous runs.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Potassium citrate acts as a moderate base and a strong buffer, resisting swings in pH when mixed with acidic or basic additives. In labs or processing lines, it forms stable complexes with calcium or magnesium ions, which helps prevent undesirable precipitation in drinks and health supplements. At higher temperatures or in the presence of strong acids, potassium citrate can break down into citric acid and potassium salts, reactions key to understanding its behavior during certain manufacturing steps or high-heat food processes. Chemists have modified potassium citrate’s structure slightly to adjust its solubility or ease of mixing, but the parent salt dominates most industrial and health applications thanks to its tried-and-true reliability.

Synonyms & Product Names

Across markets and research papers, potassium citrate answers to several names. You’ll encounter “tripotassium citrate,” “potassium citric acid salt,” or the European food code E332 (often split as E332(i) and E332(ii) for monopotassium or tripotassium forms). Pharmaceutical labels might call it “potassium citrate monohydrate” when water’s attached, or simply “potassium salt of citric acid.” Other languages and regions use their own variants, but the underlying compound remains easily identifiable through its chemical formula C6H5K3O7.

Safety & Operational Standards

Potassium citrate, classified as low-toxicity, requires basic precautions in handling—avoid dust inhalation, wash away spills, and use personal protective gear in processing plants. Overdoses or chronic heavy use can throw off the balance of electrolytes, so medical personnel track dosing and patient potassium levels when prescribing it as a drug. Food and drug safety authorities, such as the FDA and EFSA, recognize potassium citrate as Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) at normal consumption levels. Regulatory bodies expect producers to follow standards like HACCP or GMP, ensuring quality and traceability from raw material sourcing through packing. Waste management involves neutralizing dilute residues and keeping large quantities away from waterways, since excess potassium can disrupt aquatic ecosystems.

Application Area

Potassium citrate features across several sectors. Kidney stone patients often take it as a supplement or medicine, since it helps curb stone formation and regulate urinary pH. Dietitians point out its role in delivering potassium without sodium's drawbacks for those managing blood pressure or salt intake. Food scientists rely on potassium citrate as a buffering agent in soft drinks, jams, and processed cheeses, where acidity needs to stay predictable. Beverage makers lean on its flavor-balancing powers, smoothing out sour notes in fruit drinks and helps stabilize vitamin C. In manufacturing, potassium citrate might show up in detergent formulations or serve as a chelating agent in industrial water treatment. Every application benefits from its relative safety and straightforward handling procedures.

Research & Development

Researchers have pushed deeper into how potassium citrate affects renal health, bone strength, and cardiovascular function. Ongoing studies hope to unlock the best ways to harness its alkalizing action in sports nutrition and kidney care, sparking new products or improved dosing protocols. Advanced analytics, like high-performance liquid chromatography, chase down trace impurities and map out how potassium citrate behaves alongside a cocktail of nutrients or pharmaceuticals. The push for cleaner labeling means R&D labs hunt for ways to improve transparency and minimize process aids. Meanwhile, industry specialists study particle engineering and granule shape, chasing smoother dissolution and easier mixing for new delivery formats like effervescent tablets or gummies.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists have put potassium citrate under the microscope to chart its effects at different intake levels. Short-term use at therapeutic doses rarely triggers problems outside a few sensitive groups. High doses or long-term overuse can lead to excessive potassium—hyperkalemia—a risk factor for muscle weakness, irregular heartbeat, or dangerous shifts in blood chemistry. Studies continue to monitor trace contaminant risks, especially lead or arsenic that could sneak in from raw ingredients. Regulators take these findings seriously, raising the bar on supplier audits and testing standards to keep even small risks tightly controlled.

Future Prospects

As processed foods, supplements, and tailored nutrition carve out more shelf space, potassium citrate looks set to play a larger part in both health management and food innovation. New interests in lowering dietary sodium and increasing alkaline mineral intake keep this salt in demand among formulators. The shift toward plant-based diets boosts attention on non-animal derived minerals, a niche where potassium citrate already stands strong. Sustainability ranks high on buyers’ lists, triggering investment in greener manufacturing routes and waste minimization. If researchers can deepen the scientific case for potassium citrate’s long-term health benefits, expect broader use in everything from functional beverages to green tech, making this old salt a player in modern wellness and industry.

What is Potassium Citrate used for?

Real-Life Uses for Potassium Citrate

Every time I talk about dietary supplements or medications with friends or family, potassium citrate comes up more often than you'd think. It's not trendy like vitamin C, but ask anyone dealing with kidney stones or heart health. They'll tell you what a difference this mineral salt can make.

Doctors recommend potassium citrate to help prevent kidney stones, especially when regular diets or other treatments haven't done the trick. For years, kidney stones disrupted my uncle's work and family routines. The pain kept him up at night and sometimes landed him in the emergency room. His doctor suggested potassium citrate because it raises the citrate level in urine, lowering the risk for stones to form. After a few months of sticking with his prescription and adjusting his diet, my uncle's life changed. He could travel again. He didn't need to worry about that sudden stabbing pain while on a camping trip.

Protecting Kidneys and Easing Chronic Issues

It's not just about kidney stones, either. For people with certain metabolic or genetic problems, potassium citrate helps balance the acid in the blood. Most folks don't realize that a diet high in protein or certain medical conditions, like renal tubular acidosis, can turn the blood a bit more acidic than what's healthy. That acidity wears down bones and muscles over time, sometimes without people noticing until something worse crops up. Doctors use potassium citrate to help get that acid under control, supporting bone health and preventing further problems.

Improving Heart Health Through Potassium

We're often told to eat more bananas or leafy greens for potassium, but sometimes, getting enough just from food isn't practical. Potassium, including in potassium citrate form, helps nerves, muscles, and especially the heart keep a steady beat. Too little potassium can trigger muscle cramps or even more serious heart rhythm problems. People taking water pills (diuretics) for high blood pressure often lose potassium faster. Some need potassium citrate as a supplement under medical guidance.

Everyday Food Uses You Might Not Expect

I remember helping my grandmother bake cookies as a kid, reading the ingredient list, and spotting “potassium citrate.” At the time, it sounded like rocket fuel. Turns out, it keeps foods shelf-stable and maintains flavor balance without loads of sodium. Manufacturers work potassium citrate into soft drinks, jellies, and processed foods to help the food taste right and keep its texture. For people trying to cut back on salt (and lower their blood pressure in the process), potassium citrate lets food stay tasty while reducing sodium content.

Being Mindful with Potassium Citrate

While talking to healthcare professionals, I learned that too much potassium can be dangerous, especially for those with kidney disease or taking certain heart medications. Too little is a problem, but too much causes its own troubles, like irregular heartbeat or muscle weakness. Always best to get lab work first, check kidney health, and work out the right dose if potassium citrate is on the table.

Practical Solutions to Common Challenges

Pharmacists suggest starting low, checking blood levels, and adjusting the dose. For people who have trouble swallowing pills, tablets come in different sizes, and some versions dissolve in water. If grocers listed food additives clearly and doctors spent more time explaining the “why” behind prescriptions, more patients could avoid side effects or awkward hospital visits.

Most health problems don’t get solved with a magic pill, but understanding how something like potassium citrate fits into the bigger picture of diet, lifestyle, and medical care can shape better habits. Anyone considering a change in how they get potassium—either from food, supplements, or prescriptions—should always check with their care team for safe, personalized advice.

How should I take Potassium Citrate?

What Potassium Citrate Does

Potassium citrate supports people dealing with kidney stones and certain urine problems. Doctors often prescribe it when low potassium or a risk of new kidney stones turns up in blood work. This mineral works by making urine less acidic, stopping stones from forming or getting bigger. For some, it helps balance heart rhythm, especially in folks using medicines or treatments that drain potassium.

How to Take Potassium Citrate Safely

Tablets and powders both exist, but they do not go down the same way. Most people receive tablets. It’s a smart move to take potassium citrate tablets with a meal. Food cuts the chance of stomach upset, nausea, or that burning feeling as the pill moves down. Wash each dose down with a full glass of water. Water not only protects your stomach and throat but helps keep the kidneys flushing.

Some folks get a powder or a liquid. Mix the powder or liquid with at least half a cup of water or juice. Stir it well and drink it right away — do not let it sit around. The taste may turn bitter, but you can add a little more juice if swallowing gets tough. Do not crush, chew, or suck on extended-release tablets. The coating keeps medicine slower and gentler on your body. Crushing them can release too much potassium at once, and that risks heart trouble, tingling, or serious weakness.

Timing and Dosage: What Experience Teaches

Never change your dose on your own. Potassium changes happen quietly, but the effects build up. Too much can stop your heart, and too little leaves you tired, crampy, or clouded in thought. Dosing schedules usually split into two to four times a day, spaced out to keep levels steady. What works for a neighbor will not always fit you. That is why labs and check-ins happen. Your kidney specialist or family doctor watches blood and urine for a reason: the right level means safety.

Daily Realities and Risks

Taking potassium citrate may lead to some surprises. Upset stomach, mild nausea, or loose bowels come up for many, especially in the early days or at higher doses. Slow adjustments and meal timing help. Be honest with your care team about odd side effects: tingling, chest pain, weakness, or skipped heartbeats do not call for waiting. That is the time for quick action, not quiet suffering. Most emergencies from potassium citrate stem from use outside of doctor advice.

Some foods pack loads of potassium too. Bananas, citrus fruit, spinach, potatoes, and even orange juice raise natural potassium. If you already use potassium citrate, ask your doctor before piling a lot of potassium-rich foods on your plate. Combining supplements and high-potassium diets without guidance leads to trouble. Older adults and those with kidney disease run the highest risk.

Smart Choices for Long-Term Success

Feeling better or seeing stones dissolve does not mean you should quit taking the medicine on your own. Blood pressure, kidney health, and future stones all depend on steady potassium levels. If you ever forget a dose, take it as soon as possible — unless it’s close to your next scheduled time. Skipping or doubling up can both do harm. Store the medicine away from heat and moisture, somewhere kids and pets won’t find it.

In real practice, the small choices matter — honest talk with your care team, consistent meals, and regular check-ins. Potassium citrate can help, but only with careful use, a bit of patience, and a partnership with your doctor. Each step keeps your heart steady, your kidneys running well, and those painful stones at bay.

What are the possible side effects of Potassium Citrate?

Potassium Citrate and Its Purpose

Potassium citrate brings relief for kidney stone sufferers and those with certain metabolic conditions that upset acid balance. Years in the pharmacy taught me this prescription gets doled out because it raises urine’s pH and helps flush out pesky stones. Anyone handed a bottle from the counter has likely heard the pharmacist mention common things to watch out for. But that quick consult doesn’t always cover the realities you might face after starting it.

Digestive Upset: More Than Mild Nausea

The gut takes the brunt right off the bat. Stomach pain and nausea seem to show up early, often after the morning pill. Reports of loose stools aren’t rare. I’ve seen folks try to power through, thinking the worst will pass. Sometimes the cramps ease with food or a new dosing schedule, but for others it lingers. If diarrhea refuses to budge, dehydration risks pile up, especially in summer or among older adults. These daily discomforts seem minor until they chip away at someone’s resolve to stick with the medicine.

High Potassium: The Stealthy Risk

Potassium helps nerves fire and muscles—including your heart—beat smoothly. But too much causes problems fast. Doctors call it hyperkalemia, and it’s not just a textbook worry. In my time behind the counter, I saw blood tests dialed in for anyone at risk, especially those with weakened kidneys or who already take water pills or ACE inhibitors. Weakness, chest pain, and muscle twitches don’t always announce themselves loudly; they sneak up, which makes regular monitoring crucial. Published research confirms that the threat grows in people with any kidney slowdown, reinforcing why labs matter more than how someone feels alone.

Heart and Nerve Problems: What High Potassium Can Do

A racing or skipping heart isn’t something easily shrugged off. High potassium can glitch the heart’s rhythms, sending people to the ER. I recall one patient whose pulse was steady one week and then suddenly erratic the next, traced back to extra potassium from supplements piled on top of the prescribed citrate. Confusion and tingling limbs join the list. Anyone already dealing with heart troubles, or older adults slower to clear potassium, face a higher risk. Both science and real-world experience prove this isn’t a side effect to underestimate.

Managing the Risks

Doctors often recommend regular blood draws after starting potassium citrate—this step isn’t busywork. A balanced diet also matters since some high-potassium foods (bananas, spinach) add to the total. Pharmacists remind patients about interacting meds; common items like ibuprofen can magnify potassium buildup in some people. Simple reminders, like taking tablets with meals or splitting doses, cut down on stomach woes for many. But once chest pain or numbness appear, waiting it out at home turns dangerous. I’ve seen the difference a quick response makes, even if the ER trip feels like a hassle.

Why Paying Attention Matters

Potassium citrate plays a role in keeping kidneys and stones in check, but the side effects turn into real-life hassles if not monitored closely. My years in healthcare showed that the people who fare best build a clear routine—tests on schedule, meals planned with care, open talks with prescribers. A bit of vigilance and honest conversation gets better outcomes than stubbornness or guessing alone.

Can I take Potassium Citrate with other medications?

Mixing Potassium Citrate With Other Medicines: What's At Stake

Standing at the pharmacy counter with a handful of prescription bottles, many people wonder if adding a potassium citrate pill is safe. Potassium citrate supports those struggling with low potassium or certain kidney stone issues. Still, not every medicine plays nicely with it. My years helping loved ones manage their pillboxes taught me that even common combinations could cause trouble if you don’t keep your eyes open.

Interactions That Raise Red Flags

Some meds push potassium levels higher. ACE inhibitors for blood pressure control, like lisinopril, belong to that group. Add potassium citrate, and the potassium number in your blood can climb too high. The results feel nasty — heart palpitations, weakness, or even dangerous heart rhythms. I watched a neighbor hit the ER after combining two “kidney-friendly” prescriptions with a potassium supplement. Her story keeps me cautious.

Diuretics, especially ones that keep potassium around (like spironolactone or triamterene), bring similar concerns. Potassium-sparing types help some hold onto potassium but can shoot those levels up under certain conditions. Mixing both without lab checks means risking medical emergencies. On the other side, “water pills” such as furosemide remove potassium from the body, leading some doctors to recommend potassium citrate. These combos need real supervision and ongoing lab work.

Kidney Health: The Deciding Factor

Kidney function sits at the center of all these interactions. Healthy kidneys manage potassium efficiently. For people with even mild kidney impairment, clearing potassium slows down. That means taking potassium citrate puts more strain on organs that might not handle the job. I’ve seen older adults get new prescriptions without anyone double-checking their recent bloodwork. Learn from their vulnerability: kidney trouble and potassium don’t mix well without careful oversight.

Sneaky Over-the-Counter Products

Vitamins and meal replacements sometimes include potassium too. It’s easy to look past those numbers until a surprise lab result drops. Multivitamins, sports shakes, even certain fiber supplements stack up potassium across the day. Most don’t even realize the buildup until symptoms show up. Combining these extras with prescription potassium has caught plenty of people off-guard.

Proof From Research

Current guidelines from the American Heart Association and National Kidney Foundation stress monitoring potassium levels for people on any combination therapy including potassium citrate. Studies emphasize hospital cases of drug-induced hyperkalemia—high potassium—caused by multiple medicines working together. Doctors act on these facts every day but can’t watch over every pill swallowed at home.

Practical Steps For Safer Use

Potassium often gets labeled a “benign” mineral, which leads to mistakes. Lay out every prescription and supplement with your healthcare provider—not just the major prescriptions. Request periodic bloodwork to catch small changes before symptoms arise. If new medicines come along, especially blood pressure drugs, double-check interactions right away. Stick with the same pharmacy, so their system flags risky overlaps. Better to make an extra phone call than end up with a real emergency.

Seeking Reliable Information

Trustworthy sources remain essential. The FDA, Mayo Clinic, and academic health systems consistently put out clear, accessible guides about drug interactions and potassium safety. I’ve bookmarked their pages and returned to them countless times on behalf of others.

Managing medications means more than following instructions on a bottle. Taking potassium citrate with other prescriptions asks for a regular check-in, a sharp memory, and honest talk with your medical team. These habits protect health in ways quick fixes never will.

Who should not use Potassium Citrate?

Risks of Potassium Citrate in Everyday Health

Potassium citrate shows up as a trusted remedy for certain kidney stones and low potassium. Plenty of people reach for it when their doctor tries to protect their kidneys or correct an electrolyte issue. But things are never one-size-fits-all, especially with something as powerful as potassium. Drawing from my own time working alongside pharmacists, the stories stick with me—people who trusted a supplement, only to wind up with side effects that a quick check-in could have prevented. It's tempting to think every “natural” treatment works for everyone, but with potassium citrate, some folks need to steer clear.

Who Faces Harm Using Potassium Citrate?

Anyone with chronic kidney disease carries a real risk taking potassium citrate. I’ve heard nephrologists explain how damaged kidneys can't clear potassium like a healthy organ. Extra potassium starts building up, sometimes fast, leading to irregular heartbeats. Hyperkalemia, which means too much potassium in the blood, can flip from mild symptoms—like muscle weakness—to something as sudden as a cardiac arrest. According to the National Kidney Foundation, kidney patients top the list for complications from extra potassium.

People on certain blood pressure pills also run into trouble. ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and potassium-sparing diuretics (like spironolactone) all slow down potassium removal. Tossing potassium citrate on top just pushes levels higher. Some patients get surprised, thinking their doctor knows the whole supplement routine. But unless someone asks outright, the combination can slip under the radar—until lab results ring the alarm.

Anyone dealing with untreated Addison’s disease or other adrenal problems should skip potassium citrate. The adrenal glands help keep mineral levels balanced. Without them, the body gets overloaded on potassium pretty fast. It’s a tough lesson, and one that’s easiest to avoid by skipping potassium citrate altogether in these cases.

Sometimes, stomach problems mean potassium supplements should wait. If someone has a blockage, a narrowing, or takes medicines that slow down gut movement, tablets or capsules can just sit inside, slowly releasing more and more potassium into one small area. Ulcers or even perforations can result. It’s not a story you hear every day in the news, but it’s one that shows up regularly in medical case reports.

Safe Use Starts with Clear Conversations

A lot of folks don’t realize how often potassium citrate can interact with other supplements or medications. Over-the-counter anti-inflammatories and even some heart drugs can work against the kidneys. During my years working in a community pharmacy, I watched how quickly someone’s supplement list could bloat, with each item safe on its own but dangerous combined. Information sharing between doctors, pharmacists, and patients—out loud, not just on a screen—prevents the worst outcomes.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) places potassium citrate behind the counter, so doctors and pharmacists can help sort out risks before someone walks home with a bottle. Online, that gate can break down a bit, leading to more chances for unnoticed drug reactions or health problems.

What Can Be Done?

On the ground, solutions start with better awareness. If you have kidney disease, adrenal disorders, or use certain blood pressure medicines, clear it with your doctor or pharmacist before starting something like potassium citrate. Healthcare teams need to ask pointed questions, not just rely on lists. Patients should never feel embarrassed about bringing up supplements, no matter where they heard about them. Open, honest talks save lives in places where potassium citrate seems harmless.

Education from clinics, pharmacies, and community organizations can swing the needle, helping people learn which symptoms demand fast medical attention. With the rise of supplements advertised online, strong guardrails—easy to understand and widely shared—could cut the danger. It's clear that using potassium citrate safely depends on more than labeling; it means real conversations and real partnership between patients and providers.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | tripotassium 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate |

| Other names |

Tripotassium citrate Potassium salt of citric acid E332 Citrate of potash |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˈtæsiəm ˈsɪtreɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | potassium 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate |

| Other names |

Tripotassium citrate Potassium salt of citric acid E332 |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˈtæsiəm ˈsɪtreɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 866-84-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1721223 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:131379 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201567 |

| ChemSpider | 54628 |

| DrugBank | DB00630 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.153 |

| EC Number | 208-750-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 7783 |

| KEGG | C00365 |

| MeSH | D017732 |

| PubChem CID | 11370 |

| RTECS number | TS8050000 |

| UNII | 65ANW36S2K |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 866-84-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1821803 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:131379 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201733 |

| ChemSpider | 6297 |

| DrugBank | DB00630 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.675 |

| EC Number | 209-504-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 7704 |

| KEGG | C00764 |

| MeSH | D017697 |

| PubChem CID | 311 |

| RTECS number | TT2975000 |

| UNII | V8UR102RXD |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | K3C6H5O7 |

| Molar mass | 324.41 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or almost white, crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | D=1.98 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -3.3 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 8.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 11.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | \-54.0·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.49 |

| Dipole moment | 1.8 D |

| Chemical formula | K3C6H5O7 |

| Molar mass | 324.41 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | DENSITY: 1.98 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -3.3 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 3.13, pKa2 = 4.76, pKa3 = 6.40 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb = 3.1 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -52.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.498 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 2.56 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 418.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -2347.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -4188 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 324.4 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -2234 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3738 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation; causes serious eye irritation; may cause skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS hazard statement: H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 5400 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 5400 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WT2932500 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 8-16 mEq per day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory tract, eye, and skin irritation |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319, P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | No hazard statements. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P330, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 5,400 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 5400 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WT2935000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 105 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Citric acid Sodium citrate Calcium citrate Magnesium citrate Ammonium citrate |

| Related compounds |

Citric acid Monopotassium phosphate Sodium citrate Potassium bicarbonate Potassium chloride |