Potassium Carbonate: More Than Just a Basic Chemical

Historical Development

Humans have relied on potassium carbonate far longer than many realize, and its journey runs deep through centuries of daily life. Long before laboratory syntheses, wood ash from kitchen fires offered primitive versions of the compound, giving rise to potash, an essential ingredient for soap-making and glass-blowing. Early potters mixed it to lower melting points, easing their craft long before thermometers existed. In the 18th century, the chemical industry’s growing needs led to purer forms, and manufacturers began producing it by treating potash with lime, paving the way for more precise chemical control and broader industrial uses. Over time, production improved, technology advanced, and potassium carbonate transformed from a product sourced out of necessity into a mainstay for modern production lines and research laboratories.

Product Overview

At first glance, potassium carbonate may look like just another white powder, but its versatility tells a bigger story. From food processing to pharmaceuticals, it shows up where few expect—softening water in laundries, raising pH in winemaking, and helping with silk dyeing. This salt, known as K2CO3, dissolves so readily in water that it almost disappears before the stir is over, and the solution feels slippery like soap. Across different industries, its ability to control acidity and contribute potassium makes it indispensable, and that’s a reputation earned over a long, active service on factory floors and research benches.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Potassium carbonate forms colorless, odorless crystals, but don’t let the bland appearance fool you. It’s deliquescent, meaning it eagerly pulls moisture right out of the air—a trait making it handy for drying operations but challenging when it comes to storage. In water, it forms a strong alkaline solution, raising pH just the way soap does on skin. Its solubility and reactivity stem from its ionic structure, and it doesn’t burn, but it reacts fiercely with acids to produce carbon dioxide. The melting point sits around 891°C, high enough to withstand most kitchen and laboratory mishaps, and the material’s stability under regular conditions makes it safe for use when proper precautions are taken.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Factories and research labs alike depend on consistency, and that’s where specs come in. The industry expects potassium carbonate to boast at least 99% purity, with traces of chloride and sulfates kept to a strict minimum. In packaging, companies clearly spell out chemical concentration, weight, grade (food or industrial), and batch number for tracking and quality assurance. Labels also flag corrosivity and the need for proper personal protective equipment. Even small details—like the presence of water as hydrate—matter on these sheets, because process control depends on exact formulations. Listing complies with international standards, such as those from OSHA and the European REACH directives, lending extra confidence to users down the line.

Preparation Method

Modern manufacturers typically produce potassium carbonate by treating potassium hydroxide with carbon dioxide gas, a process that starts with electrolyzing brine to generate the hydroxide, followed by carbonation. The reaction produces a solution, which gets concentrated, crystallized, and dried to the desirable white solid. In some regions, traditional methods still find a home—plant ash leaching and lime mixing deliver cruder product in rural applications. Whether refined or rustic, the method reflects the needs of the user and the resources on hand, but the push for precise control leads most industrial players to favored chemical routes.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Potassium carbonate pulls its weight in countless chemical scenarios. Drop it in water and watch it dissolve with heat released, then react with acids and see carbon dioxide bubble up—a quick test no lab student forgets. Mix with calcium hydroxide, and potassium hydroxide emerges, prized for industrial alkali uses. Further modifications can create double salts or specialty reagents for analytical chemistry. Its mild basicity lets it shift the balance in organic syntheses, especially where more aggressive bases would ruin sensitive compounds. In these contexts, flexibility reigns, and a well-trained chemist finds new tricks for potassium carbonate every year.

Synonyms & Product Names

Ask for potassium carbonate in different settings, and you’ll hear a slew of names. "Potash" pops up in discussions from farm fields to soap factories, carrying tradition as much as chemistry. Trade catalogs prefer "Pearl Ash" for its historical value. The food industry codes it as E501, while chemists abbreviate it K2CO3. Each name tells a story about use, purity, or market, and keeping track of terms ensures users get exactly what they intend. Industry databases and international registries like CAS (584-08-7) and EINECS maintain clarity for anyone tracking shipments or regulatory compliance.

Safety & Operational Standards

In my years working with chemicals, few things rank higher than strict safety. Potassium carbonate must be handled with gloves and goggles, especially in concentrated form, since the high pH can irritate or burn skin and eyes. Proper ventilation is essential because dust, once airborne, causes throat and lung discomfort. Storage calls for airtight containers—humidity turns the powder to a sticky paste quickly. Facilities train staff to follow spill and exposure protocols and keep safety data sheets in reach. Industry standards, set by authorities like OSHA and the European Chemical Agency, drill in these habits, and routine audits reinforce good practice across corporate and academic labs.

Application Area

Potassium carbonate’s real appeal comes from its adaptability. Glassmakers value it for its role in reducing melting temperatures and yielding higher clarity, and food technologists use it to regulate acidity in cocoa and noodles. Laundry services add it to soften hard water, industrial chemists prepare specialty soaps and detergents, and winemakers adjust pH in fermentation tanks. My own kitchen has seen it as a leavening agent in traditional Chinese mooncakes. Beyond the home and plant, even cave explorers deploy potassium carbonate to neutralize acids on equipment. This reach means scientists and technicians trust its reliability, and the breadth of applications shows a chemical firmly embedded in daily living and commerce alike.

Research & Development

Significant R&D keeps potassium carbonate relevant as demands shift. Researchers now explore greener synthesis methods, using enzyme catalysis or reusing industrial CO2 emissions to create the compound. Traditional applications call for refinement—producing ultra-pure grades for electronics manufacturing or new crystal forms for specialty ceramics. Studies push the envelope in additive manufacturing, fuel cell electrolytes, and even carbon capture, where potassium carbonate absorbs CO2 efficiently. My own exposure to university materials labs saw funding chase pilot projects using potassium carbonate in energy storage prototypes. These explorations keep the compound front and center for future-facing industries increasingly focused on sustainability.

Toxicity Research

Potassium carbonate remains much safer compared to many industrial chemicals, yet nobody in their right mind treats it casually. Toxicologists note that ingestion or inhalation of concentrated dust causes irritation, nausea, and in extreme doses, more serious electrolyte imbalances. Research points to a low risk for carcinogenicity and mutagenicity, but the corrosive nature in eye or skin contact continues to drive safety standards higher each year. Regular studies update permissible exposure limits, and workplace health programs track long-term effects, especially in environments where daily handling occurs. Regulatory agencies draw lessons from workplace incidents across decades, using findings to refine guidelines and keep risks lower for everyone from factory workers to researchers.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, potassium carbonate holds promise that goes beyond legacy use. Energy storage and renewable energy advances draw on its buffering abilities, and environmental engineers use it for CO2 scrubbing in climate action plans. The need for high purity in electronics manufacturing remains an ongoing challenge, pushing companies to refine production processes. Agricultural scientists evaluate potassium carbonate in precision farming, tailoring fertilizer blends for efficiency and lower runoff. As sustainable methods take center stage, circular production models gain ground—recovering potassium and carbon sources from waste streams. These moves point to a future where old chemicals find new life, enabled by research and driven by the evolving needs of technology and society.

What is Potassium Carbonate used for?

The Forgotten Helper in Food and Drink

Most people eat chocolate, drink lattes, and snack on pretzels without ever considering what helps shape their flavors and textures. I still remember reading the ingredient label on my favorite Dutch cocoa powder and seeing a long chemical name—potassium carbonate. Rather than some suspicious additive, it’s actually an old friend to the kitchen. Potassium carbonate helps alkalize cocoa, giving it that rich, mellow taste that makes Dutch chocolate so smooth. In bakeries, it helps pretzels develop their signature dark skin during baking. It’s not as showy as sugar or salt, but its presence matters for taste and texture.

Guardian of Everyday Products

I’ve worked with artisan soap makers and always noticed those sacks of potassium carbonate in their storage rooms. Its ability to soften water in the soap-making process stands out. With hard water, homemade soaps can leave behind a sticky film and don’t lather much. Adding potassium carbonate neutralizes minerals, giving bars a cleaner, silkier feel. Cleaners and detergents also benefit, since softened water means less soap scum and fewer wasted cleaning agents. In glass production, the chemical helps reduce melting temperatures, saving money and energy—a detail that often gets lost in the talk about green manufacturing.

A Quiet Player in Industry

Chemical plants use huge amounts of potassium carbonate to capture carbon dioxide gas, especially in ammonia synthesis and natural gas purification. You don’t hear much about this process, but it helps control pollution and ensures safer workplaces. Lower-tech jobs, like making some fire extinguishers, make good use of potassium carbonate because it cuts through grease fires without producing toxic smoke. Some photographic developers also rely on it, even though digital cameras have shrunk the film market over the years.

Food Safety and Health: Real Concerns

Nobody wants to worry about hidden dangers in their food. Health agencies, including the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority, consider potassium carbonate safe in the small doses used for food processing. I’ve learned that overdose could upset the body’s acid-base balance, but that’s only at doses far above anything found in a chocolate bar or bakery snack. Allergy worries rarely turn up, and as a food additive, potassium carbonate doesn’t add extra calories or questionable residues. Still, manufacturers and regulators need to remain vigilant, especially as processed foods evolve and new techniques emerge.

Looking Beyond the Label: Supporting Smart Use

The practical side of me wants to see more transparency from companies. Even a short explanation on labels could help folks understand why potassium carbonate appears in their pantry staples. Many shoppers, armed with smartphones and social media, want the facts on every ingredient. If more people know that this chemical comes from wood ash and potash, and that it helps craft the foods and goods they love, maybe skepticism would shift to trust.

Better communication between producers, safety regulators, and the public ensures responsible use and less fear. In my kitchen, in the factory, and on the supermarket shelf, potassium carbonate deserves a little respect. Facts, not fear, should shape our choices—much like potassium carbonate quietly shapes what we eat, clean, and create every day.

Is Potassium Carbonate safe for consumption?

What Is Potassium Carbonate?

Potassium carbonate pops up in food science circles as E501. It looks like a white, salty powder and gets used for all kinds of things outside the lab, too. You’ll find it in baking, cocoa processing, and even ramen noodles. My time working at a bakery taught me that this is one of those hidden helpers—rarely in the spotlight, but always helping out behind the scenes.

How Is Potassium Carbonate Used in Food?

This compound changes the pH in foods. In cocoa, it helps mellow out bitter flavors and gives Dutch-processed chocolate its deep color. For some noodles, like authentic Chinese mooncake pastry or traditional alkaline-type ramen, it creates that springy, chewy bite. Bakers have known for centuries about its role in producing fluffy baked goods. Most large-scale bread factories use it as a leavening agent. Even in wine-making, potassium carbonate can stabilize acidity. It’s not just a chemical from a lab—it helps make our favorite foods as good as they are.

Is It Safe to Eat?

The big question always comes down to safety. Research shows that small amounts used in food manufacturing are generally considered safe. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists it as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS). The European Food Safety Authority has made similar statements. In kitchens and food processing, nobody is dumping handfuls of the stuff into food—it’s always measured out in tiny amounts.

Problems start at high doses, way above what someone would get in an average diet. Swallowing large quantities can irritate the digestive system, raise potassium in the blood, and create health risks, especially for people with kidney issues. I learned this in food handling training: safe handling comes down to quantity. With most things, the dose makes the poison—even something as simple as water can cause deadly problems if consumed excessively.

What Should Consumers Know?

Seeing a chemical-like name on a food label can trigger worry, but context matters. Many of these ingredients have passed safety checks, usually with lifetimes of experience and regulation. If potassium carbonate pops up in a product, it usually shows up in such small concentrations that it won’t move the needle for your health. Still, those watching their blood potassium levels—folks with kidney disease, in particular—should check with their doctor. That goes for any supplement or chemical additive, not just this one.

Improving Transparency and Trust

Manufacturers can do a better job explaining food additives like potassium carbonate. Too many labels stay vague or avoidable for the average shopper. Everyone benefits when companies post more resources online, break down ingredients, and answer consumer questions directly. Public health agencies can jump in by educating people, backing up statements with long-term studies, and sharing real-world data, not just lab results. Journals, news outlets, and educators can play their parts in making science accessible and practical—the kind of information that helps people make steady choices at the grocery store.

Smart Choices and Practical Tips

If you’re concerned about any chemical in your food, dig a little deeper. Look up reputable sources, ask a registered dietitian, and avoid the world of half-true internet scares. Potassium carbonate helps bring us better flavors, textures, and shelf life in many foods. With proper use, evidence points to it being a safe, helpful ingredient for most people. If your health demands you watch every sodium or potassium milligram, talk to someone qualified—but don’t lose sleep over a chemical that’s helped bakers and food makers for generations.

How should Potassium Carbonate be stored?

Why Care About Where and How Potassium Carbonate Sits?

Potassium carbonate comes up pretty often for folks who work with chemicals, fertilizers, glassmaking, or certain soaps. I first handled a batch during a summer job at a ceramics shop, where any old shelf wouldn’t cut it. This white powder may not look imposing, but the right storage can mean the difference between safe handling and costly mistakes.

Humidity: The Constant Enemy

Humidity likes to sneak in everywhere. Potassium carbonate draws moisture out of the air (hygroscopic is the technical term, but what matters is that it clumps up and forms a slick mess). In high humidity, the product can harden, bleed through packaging, or stick to everything. No one enjoys scraping a sludge of chemical off warehouse floors. A bone-dry storeroom, preferably with dehumidifiers running, keeps the material in top shape.

Seal It Tight, Save Yourself Some Headaches

Once a bag of potassium carbonate gets opened, it can become a race against the clock. Containers need to shut airtight. Folks often use high-density polyethylene drums or sturdy plastic pails fitted with strong lids. Forget about leaving the sack half-folded or in a cardboard box that once held printer paper. Even a little moisture sneaks in, and things start breaking down. You might lose the whole batch.

Temperature Swings Don’t Help Either

Sunbeat warehouse window? That’ll shorten the life of any chemical, potassium carbonate included. Keep it out of direct sunlight, and shoot for a spot with stable, moderate temperatures. I once worked with a supply left on a loading dock in July. By the end of the week, what was left inside looked and felt nothing like what we had ordered. Storing potassium carbonate at steady room temperature, away from sources of heat and cold drafts, makes sure it performs the way it's supposed to.

Chemical Segregation: Thinking Bigger Than Just This Product

The trouble doesn’t only start with water vapor. Mixing up storage can spell bigger problems. Potassium carbonate reacts with acids and can corrode some metals. Avoid putting it near hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, or anything with a high water content. It’s not worth stacking it with gear for pool chemicals either. Storing similar basic chemicals together and marking shelves saves confusion—and sometimes prevents dangerous reactions.

Label Everything, Always

Once or twice, I’ve seen new workers mistake potassium carbonate for baking soda. Both are white powders, but only one will make your cookies safe to eat. Clear labels—big, printed, even color-coded labels—keep everyone on the same page. For places where the law demands Material Safety Data Sheets nearby, it pays to give those docs a quick check each time you start a new job.

Don’t Forget Personal Safety

Storage isn’t just about the chemical lasting longer. The right choices help keep people protected. Gloves and glasses always come out before a storage container opens. Spills can happen, and potassium carbonate dust shouldn’t end up in eyes or lungs. An eyewash station nearby is smart, and having a broom and vacuum ready for quick cleanup means less risk.

Simple Steps, Fewer Problems

Keeping potassium carbonate dry, out of direct sunlight, shut in proper containers, labeled, and separated from acids keeps it useful and everyone safe. These habits—learned on the ground—pay back with fewer accidents, no wasted product, and a bit less stress day to day.

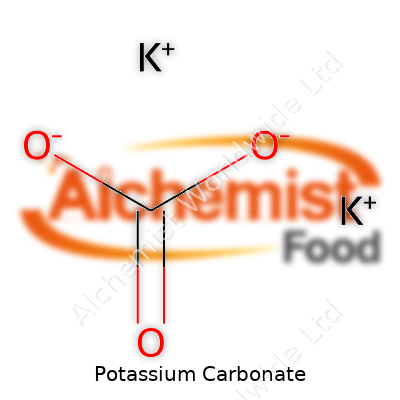

What is the chemical formula of Potassium Carbonate?

Potassium Carbonate’s Chemical Make-Up

Potassium carbonate carries the formula K2CO3. The name might sound like high-school chemistry, but this compound touches so many parts of everyday life. Two potassium atoms and one carbonate group come together to form this white, salty powder. It’s the details behind the K2CO3 formula that build all the properties people rely on, from water softening in households to the crispy snap in certain noodles.

A Familiar Face in Industry and the Home

From my own days working behind the counter in a hardware store, I often saw folks reach for Potassium carbonate because it got the job done without fuss. Soap makers leaned on it for its ability to soften hard water. Brewers found it handy to adjust pH levels during beer production. Even glass manufacturers built entire processes around it, shaping those familiar bottles and panes people use every day.

The formula, K2CO3, is not just a label but a promise. Each potassium ion does heavy lifting — helping balance acidity, driving chemical reactions that make products safer and stronger. The carbonate part brings another set of benefits, letting the compound neutralize acids or loosen stubborn grime. Knowing the formula means knowing how much to use, how it will react, and how to store it safely.

Learning from Potassium Carbonate’s Practical Role

One year, a local bakery ran into trouble with their noodles. They were sticky and limp. Someone suggested adding food-grade potassium carbonate to the dough. The difference surprised everyone: noodles turned springy and light, and all because the baker understood what K2CO3 could do. This practical advantage traces right back to the predictable chemistry behind its formula.

While it’s tempting to shrug off chemical formulas as academic, misjudging the formula quickly leads to mistakes, like damaged machinery from wrong dosages or unsafe chemical mixes. At a fertilizer plant I visited, operators avoided costly shutdowns by knowing precise ratios thanks to the clarity given by formulas like K2CO3. Each letter and number carries real consequences for workplace safety and efficiency.

Safety and Environmental Responsibility

Any time you bring a chemical into a factory, school, or home, there’s a responsibility that goes with it. K2CO3 isn’t toxic in the way some substances are, but it can irritate skin and eyes or cause problems if handled carelessly. Strong, clear labeling backed by a solid grasp of the formula makes sure anyone in contact knows what to expect.

From an environmental angle, potassium carbonate breaks down without leaving harmful residues. Municipal water treatment plants often use it in measured amounts, as its predictable composition based on its formula helps manage both safety and effectiveness.

Building Trust Through Knowledge

Knowing the formula for potassium carbonate, K2CO3, unpacks a world of practical knowledge. It provides a foundation for science teachers introducing chemistry, for workers guiding industrial processes, and for consumers wanting to understand what’s inside their products. With clear information like this, trust and product safety grow, showing that real expertise combines science with lived experience.

Can Potassium Carbonate be used in food processing?

What Potassium Carbonate Brings to the Table

Potassium carbonate isn’t as famous as table salt, but it pops up in surprising places. It’s a white, salty powder that mixes well with water. Chemists call it a “strong alkali,” but cooks and bakers just see what it can do. In food processing, potassium carbonate acts as a pH adjuster and leavening agent. You’ll spot it in certain noodles, German pretzels, cocoa, and sometimes in caramel coloring. It goes by the E number E501.

Not Just Any Ingredient

Potassium carbonate can’t be tossed into food without rules. Governments take additives seriously because there’s a big difference between a safe kitchen helper and a dangerous mistake. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists potassium carbonate as “generally recognized as safe” for certain uses, and the European Food Safety Authority takes a cautious, regulated approach as well. Used in the right amounts, it won’t threaten health for most people. Too much can be harmful—large doses may irritate the stomach or disrupt minerals in the body.

How Food Makers Use Potassium Carbonate

Some foods owe their signature taste and texture to this additive. Lye water noodles, found in many Asian dishes, have a unique springiness and yellow hue thanks to potassium carbonate. In German baking, pretzels get their deep brown crust from a bath in a potassium carbonate solution. Chocolate makers use it to mellow acidity and help cocoa powder blend smoothly into drinks.

Bakers know that it punches up rising in sweets, working alongside baking soda or on its own. It works best in recipes that ask for an alkaline touch. Some caramel colors and syrups get just the right color and flavor through careful tweaking with potassium carbonate.

Quality and Consumer Trust

Consumers expect food to be safe, pure, and clearly labeled. With the rise of “clean label” products, shoppers and manufacturers want straightforward ingredients. Potassium carbonate may sound synthetic, but so does baking soda or citric acid—and most come from natural mineral sources. Companies have a job to make sure they are sourcing pure potassium carbonate and using it in allowable ways. Regular lab testing and compliance checks go a long way toward building trust.

Potential Issues and Alternatives

Some people worry about the growing list of food additives in their meals. Others have health conditions that force them to watch their potassium intake—too much can complicate kidney problems or affect the heart. For those people, food makers have to watch levels closely or consider ingredient swaps. Baking soda, sodium carbonate, or natural alkaline extracts sometimes replace potassium carbonate in recipes. Each has its own impact on taste, color, and texture.

Looking Ahead

Potassium carbonate does an honest day’s work in food processing. Used responsibly, it gets the job done without putting people at risk. The food industry is full of innovation, and with more focus on transparency and health, makers should keep a close eye on how and where they use this additive. Regular testing, clear labels, and listening to consumer feedback make a difference.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Potassium carbonate |

| Other names |

Pearl ash Potash Dipotassium carbonate Carbonic acid dipotassium salt |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˌtæsiəm ˈkɑːrbəˌneɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Potassium carbonate |

| Other names |

Pearl ash Potash Carbonate of potash |

| Pronunciation | /poʊˌtæsiəm ˈkɑːrbəˌneɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 584-08-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | BCF879383 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:131526 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201784 |

| ChemSpider | 4946 |

| DrugBank | DB11095 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03-211-796-809-23 |

| EC Number | 209-529-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: **12704** |

| KEGG | C01023 |

| MeSH | D017749 |

| PubChem CID | 8762 |

| RTECS number | TS7750000 |

| UNII | VU55T222FJ |

| UN number | UN1841 |

| CAS Number | 584-08-7 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `K2CO3` |

| Beilstein Reference | 358726 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:131526 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201706 |

| ChemSpider | 15422 |

| DrugBank | DB11098 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.883 |

| EC Number | 209-529-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: 15544 |

| KEGG | C01426 |

| MeSH | D011104 |

| PubChem CID | 24624 |

| RTECS number | **TS7750000** |

| UNII | K8U3BW49QQ |

| UN number | UN1872 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | K2CO3 |

| Molar mass | 138.205 g/mol |

| Appearance | White, odorless, hygroscopic, crystalline solid or powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.43 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 1120 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -4.7 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.33 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 3.2 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +33.0·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.427 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | K2CO3 |

| Molar mass | 138.205 g/mol |

| Appearance | White, odorless, hygroscopic powder or granules |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.43 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 1120 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -1.57 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.33 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 3.89 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -33.4×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.427 |

| Viscosity | Viscosity: 1.50 cP (20°C, 47% solution) |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 118.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | –1151 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1130.3 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 142.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1151 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1150.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12BA01 |

| ATC code | A12BA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS hazard statement: H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P301+P312, P330 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-1 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (Oral, Rat): 1870 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 1870 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | SA1160000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | up to 5 mg/m3 |

| Main hazards | Irritating to eyes, respiratory system and skin. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS hazard statement: H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-1 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 1870 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral (rat): 1870 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | RT8475000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 2 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Potassium bicarbonate Sodium carbonate |

| Related compounds |

Potassium bicarbonate Sodium carbonate Potassium sulfate |