Nicotinic Acid: Unpacking a Century of Science, Utility, and Future Promise

Historical Development

Long before supplement bottles filled drugstore shelves, nicotinic acid—also known as niacin or vitamin B3—found its way into scientific curiosity through a mix of bread, disease, and perseverance. In the early 20th century, doctors traced the ugly grip of pellagra—a disease marked by diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and sometimes death—back to a simple nutritional deficiency. Scientists, after years of chasing the elusive “pellagra-preventive factor,” pinned it down to nicotinic acid. Public health took a giant leap forward. Crews of doctors and chemists proved that adding niacin-rich foods could erase diseases that once tore through rural communities. From lab benches with rudimentary glassware to industrial-scale production and global health rollouts, the substance earned its place as a nutritional staple and later as a pharmaceutical tool for managing cholesterol.

Product Overview

Nicotinic acid comes as a white crystalline powder. It’s got a bitter taste, and, because it’s stable under heat and air, food manufacturers toss it into everything from breakfast cereals to multivitamin pills without worrying about it breaking down. Vitamin companies press, encapsulate, and blend it a thousand different ways, selling both as a food fortifier and as a prescription drug for cholesterol control. In a pharmacy, it goes under both “niacin” and nicotinic acid; sometimes it appears as part of B-vitamin complexes, all serving much the same end—keeping basic cellular metabolism humming.

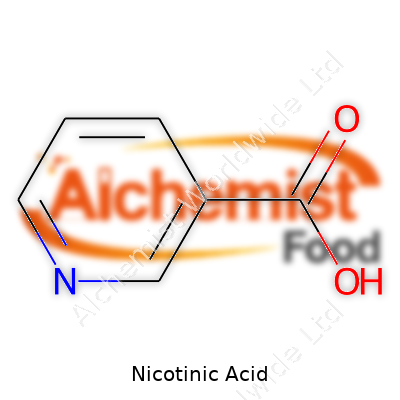

Physical & Chemical Properties

Nicotinic acid stands out for being freshwater-soluble—think easy uptake in the gut and simple mixing during manufacturing. Its melting point floats around 236-237°C, and the powder itself stays odorless. The molecule—C6H5NO2—belongs to the pyridine family, with a carboxyl group at the “3” position of the aromatic ring, separating it from close chemical cousins like nicotine. You can spot its crystalline structure under a microscope: needle-like or plate-shaped grains. Toss it in water, and it dissolves enough to let chemists dose even large batches. Forget about it breaking down at room temperature; it packs real staying power against shelf decay.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

In the world of pharmaceuticals and additives, numbers rule. For pharmaceutical use, purity often has to hit better than 99%, monitored batch by batch under pharmacopeia guidelines. Any bit of moisture has limits—5% is a typical upper threshold, as too much water clumps powders and gums up automated presses. Labels, especially on consumer products, need to nail both form—the name “nicotinic acid” or “niacin”—and function, listing everything from dosage strength, recommended intakes, safety statements, to batch codes for tracking. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority set clear boundaries on what counts as “safe” daily intake, as extremely high doses often tip over from benefit to risk.

Preparation Method

Industry usually makes nicotinic acid by oxidizing 3-methylpyridine. In practice, this involves heating the precursor with air or suitable oxidizing agents at high temperatures to shift the methyl group into a carboxyl group, finishing off as niacin. Smaller-scale labs and some older manufacturing setups lean on oxidizing nicotine or nicotinonitrile. Both routes demand controlled conditions, since byproducts and overheating can tank yield and purity. After the reaction, chemists run the crude mix through filtration, solvent crystallization, and drying, aiming for a fine white powder that checks every purity box under a microscope and through spectrum analysis.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemists have long found nicotinic acid simple enough for modifications, yet resilient as a core structure. You can convert it into nicotinamide by reacting with ammonia or an amine under gentle heating—a form that’s often friendlier to the stomach. For diagnostic kits and research reagents, the acid group gives a hook for attaching labels or making derivatives. Some researchers have built slow-release prodrugs by re-cloaking the carboxy group, reason being to stretch niacin’s presence in the bloodstream while dodging “niacin flush.” The aromatic ring survives most pH changes and mild oxidizing environments, which helps with blending into both food and pill formats that see plenty of handling.

Synonyms & Product Names

Nicotinic acid crowds vitamin guides, journals, and textbooks under several names: Niacin, Vitamin B3, Pyridine-3-carboxylic acid, Nicotinyl alcohol when reduced, and often just “B3” on fortified foods. In some countries, older labels even reference “anti-pellagra vitamin.” Prescription drug bottles use “niacin” or “nicotinic acid” interchangeably, depending on local regulations. Every synonym traces back to its core structure yet tells a story of use and discovery in nutrition, medicine, and basic science.

Safety & Operational Standards

Most of the world’s food regulatory bodies agree: Nicotinic acid works as a safe food additive and supplement when taken in recommended amounts. Trouble tends to show up when people overdo self-medication or megadose on supplements, trying to force down cholesterol. The “niacin flush”—a rush of blood to the skin, headache, tingling—often marks the first warning of pushing too far. Massive, chronic doses can scrape the liver and spiral into metabolic problems, mainly in people with pre-existing conditions. For industrial labs and supplement brands, tight controls over contamination, trace heavy metals, and batch tracking keep the compound within legal and health boundaries. OSHA and analogues worldwide expect chemical handling with gloves, eye protection, and dust extractors.

Application Area

Humans and animals need nicotinic acid for unlocking energy from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. That makes it a building block for fortifying flour and other staple foods, a move credited with stamping out pellagra across wide swaths of the United States and Europe. Doctors have called on prescription-grade nicotinic acid—often in slow-release tablets—to lower cholesterol and triglycerides, which, in turn, can cut risks for strokes and heart attacks. Beyond nutrition and medicine, researchers feed the compound into biotechnology as a supplement for cell culture media. Animal feed mixes borrow niacin to round out vitamin profiles. Chemical manufacturers use its reactivity for complex syntheses in dyes and diagnostics. The sheer spread into so many sectors shows how small molecules punch above their weight in daily health and industry.

Research & Development

R&D work on nicotinic acid continues to shine new light on both its strengths and shortfalls. Teams design better forms that lower traditional side effects—controlled-release tablets, new salts, and combinations with other lipid therapies. Gene mapping has shown that some people metabolically break down niacin in unexpected ways, making personalized dosing a likely frontier, especially in future cholesterol drugs. Scientists also watch closely for its role in NAD+ biosynthesis, tying niacin metabolism to everything from aging to immunity. On the food science side, researchers keep boosting its stability in processed foods and exploring new plant-based sources. The move to precision agriculture has meant revisiting natural niacin levels in crops and breeding strains that amp up natural content, rewarding both farmers and consumers.

Toxicity Research

The story of nicotinic acid doesn’t skip its darker side. Decades of animal and clinical data shine a light on safe limits. Human studies pinpoint the short-term tolerable upper intake at about 35 milligrams per day, though prescribed higher doses get managed with close supervision. Side effects don’t stop at the skin—persistent overuse can hammer liver function, trigger insulin resistance, and push uric acid out of balance. Some mouse and rat studies have pointed to possible birth defects at extreme, chronic exposures, but such conditions stay rare in real-world use. Toxicology testing runs alongside pharmacology nowadays. New formulations get routinely screened across model organisms long before humans swallow a single pill.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, nicotinic acid isn’t just a solved case from vitamin history. Targeted delivery systems promise steady absorption and lighter side effects for heart patients. Advances in synthetic biology have researchers eyeing greener ways to manufacture it, using engineered microbes or plant-based reactors, slashing industrial waste. Studies probing its connection to cellular aging and mitochondrial health put niacin in the running for anti-aging supplements and therapies beyond lipid control. If upcoming research opens safe, sustained pathways for boosting NAD+—the core molecule tied to niacin—new uses could surface in neuroprotection, inflammation, and maybe even lifespan extension. Whatever direction the next decade takes, both science and markets look ready to keep rewriting the story of this hard-working, well-tested nitrogen ring.

What are the health benefits of Nicotinic Acid?

Understanding Nicotinic Acid

Nicotinic acid, also known as niacin or vitamin B3, has earned a spot on my breakfast table more times than I can count. In my twenties, I rarely thought about the B vitamins packed into my food. With age, I started paying attention. Doctors point out that nicotinic acid helps the body convert food into usable energy. That matters a lot on groggy mornings and long workdays. Without enough niacin, fatigue creeps in and everyday tasks seem tougher.

A Cholesterol Fighter Backed by Science

People with a family history of high cholesterol often hear about statins, but few realize how effective nicotinic acid can be in the right circumstances. Multiple clinical studies show that niacin supports heart health by raising HDL cholesterol, the “good” cholesterol, and lowering LDL, the “bad” cholesterol, plus trimming triglycerides. The American Heart Association lists nicotinic acid as a proven therapy in adults who cannot tolerate statin medications or need additional cholesterol control. After watching my uncle’s numbers shift in the right direction with a doctor-supervised niacin regimen, this benefit really hit home.

Supporting Nervous System and Mental Health

Many overlook that niacin also safeguards the nervous system. Nerves depend on vitamins for proper communication, balance, and quick responses. A niacin shortage can lead to trouble concentrating, irritability, and even depression. Researchers at Harvard have published reports linking long-term, mild deficiency of niacin with a greater risk for memory loss conditions. Filling in those dietary gaps with niacin-rich foods (like fish and peanuts) or supplements, based on a doctor's advice, can support better brain function. A neighbor recovering from an illness regained energy and mental sharpness after adjusting her diet to include more niacin.

Better Skin and Digestive Health

Niacin’s impact extends to the skin and digestive system. I learned this firsthand after battling winter skin issues and flaky patches. After upping my intake of B vitamins, those symptoms faded. Nicotinic acid plays a role in skin barrier repair and helps maintain smooth, healthy skin. Dermatologists sometimes recommend it for certain skin conditions.

On the digestive front, niacin helps the body break down fats, proteins, and carbohydrates from food. Without it, digestion may slow and gut discomfort appears. The Pellagra outbreaks of the early twentieth century, marked by skin problems, diarrhea, and mental confusion, stemmed from niacin deficiency. That story sticks with me as proof that this nutrient isn’t an afterthought.

Smart Ways to Benefit

Getting niacin from real food—meat, fish, nuts, and whole grains—has always worked best in my experience. That said, supplements prescribed by a healthcare provider become necessary for some people, especially when dealing with cholesterol or certain absorption problems. Taking high doses can bring unwanted side effects like flushing or liver strain, so going overboard without supervision makes health risks likely.

A simple blood test from a doctor can check if your levels run low. Eating balanced meals with enough protein, leafy greens, and seeds usually gives most people what they need. If your doctor suggests extra niacin, be sure to report any new symptoms. By paying attention and making small adjustments, it’s possible to protect heart health, nervous function, and even keep skin and digestion on track—all thanks to nicotinic acid.

What is the recommended dosage for Nicotinic Acid?

Understanding Nicotinic Acid

Nicotinic acid, also called niacin or vitamin B3, holds a unique place in nutrition and medicine. This nutrient supports metabolism, energy production, and DNA repair. For decades, doctors have used higher doses of nicotinic acid to lower bad cholesterol and boost good cholesterol. The body does not make much by itself, so regular intake through food or supplements keeps levels healthy.

What the Science Says About Dosage

The National Institutes of Health sets a recommended daily intake of 16 mg for men and 14 mg for women. These amounts cover basic needs, preventing deficiencies like pellagra. Food sources—meat, fish, grains, peanuts—deliver enough for most. On the other hand, doctors sometimes prescribe high doses, up to 2000 mg daily, for treating high cholesterol or severe deficiency. Those high doses work differently than nutritional needs and call for close medical supervision. Too much niacin can cause flushing, liver stress, and even stomach ulcers.

Why Dose Matters—From My Own Experience

Years ago, my father’s doctor recommended high-dose niacin for stubborn cholesterol numbers. The pills left him flushed and itchy, rough enough to stop him from taking doses consistently. We worked with the doctor to find a lower, split dose, building up slowly and always monitoring liver numbers. His experience reminds me how individual each situation becomes, and that more isn’t always better.

Risks of Going Overboard

People sometimes see vitamins as safe at any dose, but niacin breaks that rule. Even at levels over 50 mg per day, some notice reddening of the skin or tingling. Going over 1000 mg increases the risk for liver damage and digestive upset. Extended-release pills can seem gentler at first but carry their own risks if misused. The FDA requires a warning on non-prescription niacin above low doses for good reason.

Practical Approaches to Using Nicotinic Acid

For most, eating well covers daily needs without extra pills. Meat, mushrooms, and enriched cereals do their job. If a doctor prescribes extra niacin for specific health problems, it pays to follow their guidance carefully. Splitting the dose, taking it with food, and sticking with regular lab tests can help avoid side effects. Skipping alcohol and limiting acetaminophen gives the liver an easier ride.

Potential Solutions for Common Concerns

Several companies offer flush-free niacin, marketed for gentle support, yet these products contain a different form—inositol hexanicotinate—that does not lower cholesterol the same way. It may relieve the skin sensation but misses the medicinal benefits of true nicotinic acid for lipids. For those sensitive to flushing, building up the dose slowly, starting below 100 mg and working with a doctor, often helps.

Final Thoughts

The right dose of nicotinic acid depends on individual health goals, risks, and doctor input. As with most nutrients and medications, balance counts more than high numbers. A thoughtful, informed approach protects both health and peace of mind better than any supplement alone ever could.

Are there any side effects of taking Nicotinic Acid?

Understanding Nicotinic Acid

Nicotinic acid, also known as niacin or vitamin B3, shows up in many medicine cabinets, often for cholesterol management. Plenty of folks hear about how it helps boost "good" HDL cholesterol. Doctors sometimes prescribe it in higher doses to cut heart attack risk, especially for people struggling with high cholesterol even after changing diet and exercise routines.

Common Side Effects in Real Life

Anyone who’s ever taken a prescription dose of nicotinic acid remembers “flushing.” That word doesn’t do the sensation justice. The face and chest go tomato red. Some people feel burning and itching that lasts half an hour or more. This blood vessel widening happens in almost everyone using regular niacin, and for some, the discomfort makes them stop taking it.

I remember seeing patients at the pharmacy counter, faces bright pink, fanning themselves and asking, “Does this ever stop?” The answer is: a little. Many find the flushing eases up with regular use, or they take an aspirin half an hour before the pill, but it never goes away completely for some.

Another side effect: upset stomach. Nausea, bloating, and sometimes even vomiting can make sticking with the medicine difficult. Taking it with food makes a difference. Doctors usually recommend a slow-release version of niacin to help with this, but it brings in other potential issues.

Looking Closer at the Risks

The unwanted effects go further than flushing and stomach grumbles. High doses, especially from prescription forms, can push liver enzymes into dangerous territory. Over months or years, people may develop hepatitis or significant liver damage. A patient with unexplained fatigue, yellow skin, or abdominal pain on niacin always makes me want to check liver tests quickly.

Blood sugar goes up in some, too. Anyone with diabetes should know that nicotinic acid may worsen glucose control. Even those without diabetes sometimes show mild increases in blood sugar. Gout – a nasty joint pain from sharp uric acid crystals – becomes more likely, as niacin raises uric acid levels.

A few people will see vision changes or even develop macular edema, a swelling at the back of the eye. This side effect isn’t common, but it’s serious enough for regular eye checkups if someone needs long-term high-dose niacin.

Why It Matters

In the real world, side effects affect whether people stick to medicine plans. It’s not enough for a pill to help on paper; folks need to tolerate it well enough to stay healthy day after day. Prescription niacin often sits on the shelf because of flushing, digestive distress, or lab changes. I’ve had conversations with patients and their doctors about whether the benefits outweigh these daily frustrations.

Finding Better Paths

Everyone considering nicotinic acid for cholesterol should talk openly with their healthcare provider. A good doctor checks the big picture: cholesterol numbers, liver health, glucose, and the real likelihood that niacin will add enough benefit, especially with today’s other cholesterol medications available. Some people may find diet, exercise, and statin drugs give better balance. Others may take a careful, monitored trial of niacin, using small doses, food, or aspirin to cut the discomfort.

The truth about side effects isn’t meant to scare people off, but it highlights why no medicine fits everyone. Listening to your body and staying honest about symptoms — both in the pharmacy and the doctor’s office — leads to safer and smarter use.

Can Nicotinic Acid help lower cholesterol levels?

Understanding Nicotinic Acid in the World of Cholesterol

People have wrestled with cholesterol for decades. Medications, special diets, exercise regimens—most folks either know someone who’s on this journey or walk it themselves. Among the different medications, nicotinic acid, better known as niacin, often comes up as a conversation starter in doctors’ offices. It’s not new on the scene, but it keeps making headlines for its impact on cholesterol.

What Does Niacin Actually Do?

Niacin acts as a B vitamin, yet at high doses it pulls double duty by improving cholesterol numbers. Doctors have prescribed it to knock down levels of LDL, or “bad” cholesterol, and to bump up HDL, the “good” cholesterol. Back in medical school, some folks joked about niacin’s ability to blow off the cobwebs in your arteries. While they exaggerated, a body of clinical studies reveals that niacin lowers LDL by around 10 to 20 percent and can lift HDL by 15 to 35 percent. Those percentages beat almost anything someone gets from the vitamin aisle at a pharmacy. That’s not just some vitamin buzz—these numbers matter for those aiming to lower their risk of heart issues.

Research published in the New England Journal of Medicine shows niacin’s effects work best for people struggling with stubborn cholesterol, especially when statins aren’t enough or can’t be tolerated. The Coronary Drug Project from decades ago even found fewer heart attacks in men who took niacin compared to those who did not. The drug stands as one of the few options outside of statins offering both LDL reduction and HDL support. That combination can be tough to find in a single pill.

Looking at Drawbacks and Safety

Niacin brings its own challenges. Many patients quit because of intense facial flushing, an embarrassing and uncomfortable heat that can turn cheeks bright red for an hour or more. Doctors often recommend taking baby aspirin before the niacin dose or using extended-release versions, but not everyone gets relief. I’ve seen patients stick it out for a while before switching medications out of frustration.

More concerning, high doses can boost blood sugar and strain the liver. For people battling type 2 diabetes or already coping with liver problems, niacin draws extra caution. Regular blood work becomes non-negotiable. With statins and other new agents now widely available, many clinicians hesitate to start niacin unless the benefits seriously outweigh these risks.

Finding a Path Forward

Lifestyle still holds the most weight. Nobody wants to hear that, but most doctors who work with cholesterol cases start by encouraging better eating and regular exercise. For some, even the best lifestyle efforts come up short. In those cases, niacin may sneak into the conversation, especially if the goal includes boosting HDL cholesterol more than statins provide. Combination therapies sometimes work better: niacin paired with other cholesterol-lowering agents displays more muscle for the trickiest cholesterol profiles.

Pharmacists always tell their customers not to buy high-dose niacin off the shelf and self-treat. Liver toxicity and other dangers depend heavily on the form and dose, so any path forward with niacin happens with medical supervision. Patients deserve honest talk about both the impact and side effects before choosing a direction.

In the end, niacin finds relevance for very specific situations, backed by decades of scientific observation. Doctors and patients benefit from looking past the hype, weighing the risks, and remembering that health does not hinge on a single pill.

Is Nicotinic Acid the same as Niacin?

Understanding the Names

Doctors and nutrition labels often list vitamin B3 as either niacin or nicotinic acid. At the pharmacy, both names pop up on supplement bottles. It’s easy to get confused, and understandably so. I remember standing in front of the supplements aisle, wondering if I was getting the correct thing for my father’s cholesterol. Turns out, the answer isn’t complicated. Niacin is the broad term for vitamin B3. Nicotinic acid is a specific form of niacin. The body can use both, but their benefits and even their side effects sometimes differ.

Biology and Benefits

On a nutrition label, “niacin” refers to two main molecules: nicotinic acid and niacinamide (also called nicotinamide). Both raise your B3 intake, but they don’t work exactly the same way in the body. Nicotinic acid has been used for decades to manage cholesterol. Doctors sometimes recommend it for people who can’t take statins. My aunt took prescription-strength nicotinic acid to lower her “bad” cholesterol, and it worked. There’s strong research proving that nicotinic acid boosts good cholesterol and cuts bad cholesterol, but large doses bring a notorious side effect—flushing. Niacinamide doesn’t have the same cholesterol benefits, but it still offers what your body needs for energy production and cell repair.

Side Effects and Concerns

The grocery store versions of niacin are mostly nicotinamide, not nicotinic acid. Why? Nicotinic acid makes your face and chest flush. Doctors warn about uncomfortable tingling, redness, or even dizziness right after swallowing a big dose. Some people can’t tolerate it, especially if they already have heart or liver problems. Niacinamide avoids those symptoms, which explains its spot in most multivitamins and over-the-counter products. But if your goal is managing high cholesterol, popping a niacinamide pill won’t help like nicotinic acid does.

Quality, Dosing, and Trust

Doctors don’t recommend treating cholesterol with over-the-counter niacin. A bottle on the shelf might not match what’s printed on the label. Self-dosing can cause liver damage and mess up blood sugar. I’ve seen friends try to “DIY” high-dose niacin without a doctor’s help, only to end up struggling with nausea and headaches. If a doctor thinks you need pharmaceutical-grade nicotinic acid, there’s a reason it comes with blood test monitoring. So, trust your doctor more than an internet article if you get a prescription.

Diet and Everyday Health

Most people meet their vitamin B3 needs through food. Chicken, peanuts, mushrooms, and tuna deliver plenty of niacin. Deficiency is rare in well-nourished populations. Pellagra, a disease caused by niacin deficiency, is mostly seen where corn is the staple food and there’s little variety. I’ve volunteered at clinics in rural areas where fortified cereals and basic supplements wipe out signs of deficiency quickly. For those eating a regular, balanced diet, extra supplements often aren’t helpful and can bring unwanted side effects if megadosed.

Making Smart Choices

Getting clear about what’s in your supplement bottle saves everyone hassle. Read the label. If you want cholesterol support, talk to a healthcare professional about prescription nicotinic acid. For plain nutritional support, the “niacin” in most multivitamins is usually enough. Science doesn’t support chasing megadoses for everyone. Eating well, listening to your healthcare team, and only using strong supplements when truly needed works better than trusting the fine print on a bottle.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | pyridine-3-carboxylic acid |

| Other names |

Niacin Vitamin B3 Pyridine-3-carboxylic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˌnɪk.əˈtɪn.ɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | pyridine-3-carboxylic acid |

| Other names |

Niacin Vitamin B3 Pellagra Preventive Factor 3-Pyridinecarboxylic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˌnɪk.əˈtɪn.ɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 59-67-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1209249 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15940 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL936 |

| ChemSpider | 836 |

| DrugBank | DB00627 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.135 |

| EC Number | 1.3.1.28 |

| Gmelin Reference | 6269 |

| KEGG | C00153 |

| MeSH | D009536 |

| PubChem CID | 938 |

| RTECS number | QR7175000 |

| UNII | 2679MF687A |

| UN number | UN2728 |

| CAS Number | 59-67-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 103957 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15940 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL476 |

| ChemSpider | 1025 |

| DrugBank | DB00627 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.719 |

| EC Number | 3.5.1.19 |

| Gmelin Reference | 822 |

| KEGG | C00153 |

| MeSH | D009540 |

| PubChem CID | 938 |

| RTECS number | QM1180000 |

| UNII | 2679MF687A |

| UN number | UN 2811 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H5NO2 |

| Molar mass | 123.11 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.48 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Water: 1 g/15 mL |

| log P | 0.57 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.1 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.85 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 5.39 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -66.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.613 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 3.04 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H5NO2 |

| Molar mass | 123.11 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.473 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -0.59 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.000011 hPa (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 4.75 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.76 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -52.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.613 |

| Viscosity | Viscosity: 1.64 mPa·s |

| Dipole moment | 3.31 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 146.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -338.9 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1446 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 143.96 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -298.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −2194 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | C10AD02 |

| ATC code | C10AD02 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | 160°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 480 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 7000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 4.96 g/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | RN=59-67-6 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) of Nicotinic Acid: 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302, H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 2, Flammability: 1, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Flash point | 174 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 460 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 7000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 4,960 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | RA0165000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL = "10 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 250 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Isomer Nicotinamide Derivative Niacinamide Conjugate acid of Nicotinate Conjugate base of Nicotinic acid |

| Related compounds |

Niacinamide Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide Nicotinic acid riboside Nicotinic acid hydrazide |