Malic Acid: From Orchard Origins to Industry Innovation

Historical Development

Malic acid owes a lot to apples. Johann Carl Wilhelm Scheele first isolated it from apple juice in the late 18th century, and the story kicked off right from nature’s pantry. Back then, food science looked a lot like kitchen tinkering, and without fancy lab gear, researchers saw value in food’s sour kick. The drive to explore this simple but powerful ingredient saw it quickly become a favorite for preserving and flavoring fruit products well into the industrial age. Those who worked with the growing processed food sector recognized the kind of tang that malic acid delivers as both familiar and desirable. As demand for consistent product quality in beverages, confections, and prepared foods increased, chemists looked for scalable ways to produce malic acid beyond just squeezing apples. Once synthetic routes became commercially viable, malic acid earned a permanent place alongside citric acid and ascorbic acid, putting home cooks and global manufacturers on even footing.

Product Overview

Ask any food scientist about malic acid and they’ll tell you it’s the acid you taste every time you eat a Granny Smith apple. It boosts tartness, balances sweetness, and extends shelf life in everything from soft drinks to baked goods. Beyond taste, it supports product pH stability, preventing unwanted microbial growth. Suppliers offer malic acid in food, pharmaceutical, and technical grades, with food-grade versions making up the bulk of global usage. Factories receive malic acid in crystalline or powder form, distributed in airtight packaging to keep moisture out and ensure it performs batch after batch.

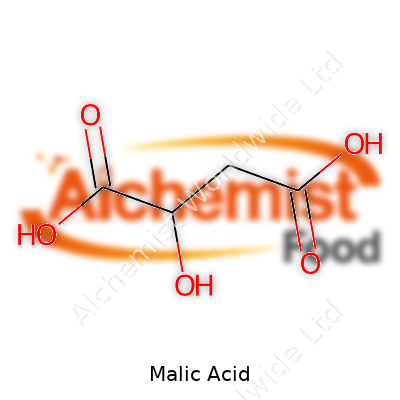

Physical & Chemical Properties

Malic acid comes in colorless, odorless crystals that dissolve easily in water, creating a mildly sour solution. With a molar mass of 134.09 g/mol and melting point around 130°C, it holds its own in moderate heat but breaks down if pushed too far. Its pKa values (3.4 and 5.1) put it right where manufacturers need it for acidulant work, and its chirality gives D- and L- forms, though the L-form dominates in nature. A little goes a long way in recipes, and the acid’s solubility means it integrates quickly with other ingredients — no lumps or slow dissolving.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labeling regulations demand transparency, and malic acid gets listed as either a food additive or ingredient, carrying the E296 code in the European Union. The U.S. FDA categorizes it as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) for its intended uses. Any product containing malic acid needs to declare its purpose — acidulant, flavor enhancer, or preservative. Specifications call for strict purity, with technical documents outlining limits for heavy metals, lead, arsenic, and chlorides. Typical packaging includes moisture-proof bags lined with food-safe inner layers, and suppliers must include date codes and batch numbers for traceability.

Preparation Method

Historically, obtaining malic acid meant lots of fruit pressing, but that’s hardly practical for today’s scale. Today’s manufacturers rely on hydration of maleic anhydride, a petrochemical derivative, in water using catalysts. Some producers turn to enzymatic fermentation methods, feeding sugar-rich substrates like corn syrup to specific yeast or fungal cultures, resulting in L-malic acid favored by the food and beverage sector. These methods allow for precise control over enantiomer ratios, process yields, and trace impurities, addressing both regulatory and functional market demands. Each production run finishes with purification, crystallization, and drying before packaging for shipment.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Malic acid provides two carboxyl groups and one hydroxyl group, making it a flexible building block for esters and salts. Food-grade esters of malic acid, like monoammonium or monosodium malate, see use in flavor maskers and mineral supplements. In baking, malic acid’s slow acidulation profile helps release carbon dioxide gradually with leavening agents, making it a favorite for cake mixes. Chemical engineers tweak its reactivity to design functional analogs for special applications — everything from biodegradable plasticizers to chelating agents in water treatment. Rare as it is, malic acid sometimes even finds its way into pharmaceutical synthesis chains, helping chiral drugs express their proper orientation.

Synonyms & Product Names

People recognize malic acid under several names: hydroxybutanedioic acid, apple acid, or E296 in regulatory circles. Its acid form appears on ingredient labels, while salt forms — such as calcium malate or potassium malate — pop up in dietary supplements and fortified foods. Different industries might call it by order code or trade name, but most food manufacturers know exactly what to expect when they source “DL-malic acid” or “L-malic acid” for specific applications.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safe use of malic acid revolves around concentration, cleanliness, and quality assurance. At typical dietary levels, it poses low risk, but exceeding clinical dosages invites digestive upset and, in rare cases, kidney stress in sensitive populations. Occupational safety guidelines treat malic acid dust with respect: dust masks, eye protection, and gloves reduce risk of irritation. Industrial cleaning protocols prevent cross-contamination in shared processing lines, and regular audits check storage area temperature and humidity to avoid product clumping. Regulatory agencies worldwide echo a similar message: stick to tested limits, document everything, and respond quickly if there’s evidence of contamination or mislabeling.

Application Area

Malic acid’s reach extends across food, drink, pharmaceuticals, animal feed, and specialty chemicals. Beverage makers add it to fruit juices, carbonated sodas, and sports drinks to sharpen sour notes or balance sugar curves. Candy manufacturers swear by it for chewy gummies, hard candies, and even powdered sour coatings, where its delayed onset enhances consumer experience. Cooks rely on malic acid in barbecue sauces, dressings, jams, and preserves to replace or complement vinegar and citric acid. Pharmaceutical companies use its chiral properties in enantiomeric drug synthesis, and even hobbyists use it for home brewing or winemaking to fine-tune the pH. Pet food and livestock supplements feature malic acid for palatability and as a digestive aid.

Research & Development

R&D teams put malic acid under the microscope for both new and existing markets. Flavor technologists experiment with malic acid’s synergy with high-intensity sweeteners to design sugar-free treats with less aftertaste. Researchers in dairy develop yogurt and plant-based alternatives with a more natural tartness. In biodegradable plastics, some teams see hope in malic acid-based polyesters as a more sustainable alternative to fossil-derived monomers. Health-focused projects look into malic acid’s role in reducing fatigue, with several studies probing its effect on cellular energy cycles as part of magnesium malate supplements. More technical branches of R&D weigh bio-based production methods, using yeast strains or engineered bacteria to keep costs down and reduce petrochemical appetites.

Toxicity Research

Toxicology research keeps a sharp eye on malic acid’s metabolic pathway. Rodent studies and human clinical trials consistently show rapid metabolism into less potent acids, like fumaric and succinic acid, followed by swift excretion. High-dose ingestion highlights only mild stomach upset, a key reason regulatory agencies approve its use across food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical sectors. Long-term studies look for genetic or reproductive risks, so far without red flags at dietary exposure levels. Research continues, though, keeping tabs on synthetic byproducts or contaminants that may result from shortcut production methods.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, industry buzzes about malic acid’s potential in green chemistry and clean-label food solutions. Consumer demand for natural and vegan ingredients puts pressure on manufacturers to phase out petroleum-based production. This trend pushes companies to invest in fermentation pathways and sustainable supply chains. Malic acid’s compatibility with plant-based proteins and non-dairy beverages opens new markets, and with governments tightening rules on food waste, its dough-conditioning and flavor-enhancing properties look more valuable than ever. Functional food developers test its performance in oral care, energy supplements, and even skincare, hoping to catch the next wellness trend. Regulatory updates and stricter standards will require constant vigilance, but for those in the acidulant market, malic acid’s future promises growth for anyone willing to pair science with market savvy.

What are the main uses of Malic Acid?

Understanding What Malic Acid Does

Malic acid shows up in a lot of places you might not expect—mostly in food, drinks, and even personal care. It’s that crisp, tart taste you notice in green apples. My earliest brush with it came from childhood snacks, long before I ever thought about what made things taste sour. Malic acid doesn’t just make food pop; it brings a lot more to the table, especially as food science keeps growing.

Food and Drink: Flavor, Freshness, and More

Walk down any grocery aisle, pick up a packaged candy, sports drink, or even a fruit jam, and there’s a good chance you’ll spot malic acid on the label. Candy companies favor it for that mouth-puckering zing, but there’s real practical value in how it tweaks flavor. Chefs and food manufacturers rely on it to boost fruit flavors and balance sweetness in juices and sodas. This acid also helps baked goods stay fresher a little longer by dropping the pH—slowing down spoilage. It’s not just about the taste but also about helping preserve that taste until you actually eat the snack.

As someone who went through a phase of making my own jams and jellies, adding a bit of malic acid gave them that cleaner, sharper fruit hit. Without it, recipes often taste flat. Some craft brewers use it to give hard ciders a punchier, refreshing tang. Looking behind the shelves, its use in processed potato snacks keeps the colors brighter for longer.

Health and Fitness Products

Malic acid makes its way into nutrition and exercise supplements, especially those aimed at muscle recovery. The thinking is that it works together with other ingredients like magnesium to support energy production in cells. Malic acid is a part of the Krebs cycle, a core process that helps turn food into energy. There aren’t sweeping miracle claims, but several supplement brands point to some clinical evidence suggesting benefits for people who feel constant fatigue, particularly with conditions like fibromyalgia.

Makes a Difference in Skincare

Plenty of facial cleansers, serums, and lotions list malic acid among their active ingredients. It’s classified as an alpha hydroxy acid (AHA), which helps exfoliate the skin. I’ve talked to dermatologists who recommend using products with AHAs like malic acid for smoother skin texture, especially if you tend to get clogged pores. Its moderate strength makes it a middle ground for people with sensitive skin, providing exfoliation without as much risk for irritation.

Industrial Uses: More Than Just Food

Outside the kitchen and medicine cabinet, malic acid finds real-world uses in metal cleaning and textile finishing. It’s no big secret among people working with technical solutions—it helps strip away unwanted films and deposits. Some manufacturers blend it into cleaning products so they cut through minerals in hard water faster. Even though most folks won’t see malic acid at work here, it quietly helps keep machinery running and makes cleaning jobs less of a headache.

Taking a Practical Approach

Plenty of ingredients get buzz for being natural or lab-made, but malic acid stands out for doing its job across fields without much controversy. If you’re worried about food additives, history points to safe use in moderation. Groups like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority lean on solid research, keeping an eye on how much ends up in your food or creams. Solutions start with clear labeling and open science, not just dropping ingredients people don’t understand. Choosing products with malic acid usually comes down to whether you want that fresh taste, brighter skin, or easy cleaning—and most times, it delivers.

Is Malic Acid safe for consumption?

Understanding Malic Acid

Every time I bite into a green apple and feel that crisp tartness, malic acid comes to mind. It’s a naturally occurring substance that flavors fruits like apples, cherries, grapes, and even tomatoes. For years, food companies have relied on this sour power to enhance snacks, candies, and beverages, giving that signature tangy kick. People often wonder about its impact on health, since it pops up on ingredient labels in everything from hard candy to “natural flavor” blends.

How Our Bodies Handle Malic Acid

I’ve read the science, and my personal curiosity led me to dig further. Malic acid plays a key role in the Krebs cycle—the essential process our cells use to create energy. Our bodies actually make this compound every day, turning sugars and starches into fuel. So, in moderation, malic acid doesn’t act like some foreign invader; it functions as a basic building block inside us.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) includes malic acid on its list of ingredients “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) for use in food. Experienced toxicologists have reviewed the research with careful eyes. Animal studies found no toxic effects at typical consumption levels. Even at doses many times higher than the amounts in a diet, test subjects did not experience ill effects.

Safety in Everyday Foods

Looking through store shelves, I see malic acid popping up in powdered drinks, gummies, jams, and even some yogurts. The amounts in these products are small, usually under 3 grams per kilogram of food. In my own kitchen adventures, adding a pinch to cider brings out a pleasant sourness—too much and the flavor goes overboard, which keeps excessive intake in check for most people.

Some folks feel a brief irritation on the tongue or cheeks after eating especially sour candies packed with malic acid. I’ve experienced that after too much sour powder at once, but the tingling passes quickly with a rinse of water and doesn’t linger.

Malic Acid in Dietary Supplements

People with muscle discomfort or chronic fatigue sometimes take malic acid supplements, hoping for relief. Studies so far haven’t shown serious side effects in recommended doses, though larger trials would help clarify any long-term risks. The human body breaks the compound down easily, and kidneys flush out any excess.

It’s always wise to ask a healthcare professional before adding something new, especially for those with kidney problems, since high intakes could add stress for individuals with reduced kidney function.

Supporting Sound Consumption Choices

While writing about food safety over the years, transparency has always stood out. It helps to read labels carefully, check sources, and focus on whole foods where possible. For people sensitive to food acids, steering clear of large amounts of sour candy prevents discomfort.

Food companies follow strict guidelines for additives like malic acid. Multiple independent organizations, including regulatory bodies inside and outside the U.S., continue to monitor its effects in line with evolving scientific evidence.

My experience and recent research support what many nutritionists say—malic acid, in moderate amounts from real foods or standard processed products, doesn’t present a health risk for most folks. Extreme sour candy binges are better kept as rare treats. Sticking to balance, reading up on ingredients, and checking in with science-backed sources guide my choices.

What are the benefits of using Malic Acid in food products?

The Tangy Punch That Stays

Biting into a sour apple gives your taste buds a lift. Malic acid brings out that same punch in candy, drinks, and snacks. I grew up nibbling on sour gummy worms that made my mouth water, thanks to malic acid. Food makers use this organic compound mainly harvested from apples and other fruits, to sharpen flavors. It doesn’t just stop at candy. Drinks get a boost, sauces pop a bit more, and baked goods gain a tart kick. People remember how something tastes, and malic acid leaves fans hungry for more.

Better Shelf Life Without the Fuss

One thing that stands out is how malic acid helps keep food fresh. Bacteria don’t like acidic environments. By lowering the pH level of products, malic acid sets up a zone where spoilage slows down. That means your favorite fruit snacks or sports drink don’t turn bad on you as quickly—even if you left them in a hot car. Reducing food waste matters in every home, especially when groceries come at a premium. It’s practical and helps both families and shops get the most out of what they buy or sell.

Clean Label, Fewer Calories

Plenty of folks look to cut sugar without losing flavor. Sweeteners often leave an off aftertaste, but malic acid smooths that out. Sweet drinks turn crisp instead of cloying, and calorie counts inch down. That’s a big deal for people watching their intake or living with diabetes. It works in ice creams, sodas, and gelatins—offering real improvements across the board. Shoppers lean toward labels with fewer additives, and malic acid fits right in since it’s naturally found in fruit.

Texture That Holds Up

Texture is just as important as taste. Chewy candies soften at the right rate with a dose of malic acid. In processed foods, this acid stops jellies and preserves from turning watery. Salad dressings stay smooth. I’ve noticed my homemade jams last longer and keep their gel better with a touch of malic acid added, especially in fruit batches that need a tart lift. The difference is clear: food doesn’t just taste better, it holds together better.

Friendly to Special Diets

More people ask for vegan, gluten-free, and allergy-conscious snacks. Malic acid meets these needs with no animal by-products or wheat hidden inside. Big brands and small bakeries alike lean on malic acid to create foods anyone can enjoy. It takes effort to feed a mixed group—think bake sales or school lunches—so ingredients like this make life easier for busy parents and chefs alike.

Solutions for Industry and Home

Using malic acid isn’t about chasing fads. It solves real problems in flavor and preservation. Cutting sugar matters for health. Keeping food safe and tasty for longer saves dollars and cuts waste. I see food companies launching new drinks and snacks almost every month, and the tart punch almost always plays in the recipe list. People expect transparency, and malic acid’s fruit origins check off another box for trust. It’s the kind of everyday ingredient that quietly makes food better—both at home and on grocery store shelves.

Are there any side effects of Malic Acid?

Malic Acid: More Than a Tart Flavor

Malic acid gives green apples their signature tang. Food makers often use it to punch up sourness in candies, sodas, and even supplements. Most people take in malic acid through fruit-rich diets without giving it a thought. Compared to synthetic additives with complicated health records, malic acid shows up naturally and in small amounts in meals, so it's easy to overlook any risk.

Can Malic Acid Cause Problems?

For most, malic acid in food doesn’t cause trouble. Eating a crisp Granny Smith apple, drinking fruit juice, or chewing a tart gummy doesn’t upset digestion. Things change with higher concentrations, like malic acid in powder or supplement form. Those aiming for improved energy, relief from fibromyalgia, or help with dry mouth sometimes take it in capsules or larger doses. At this level, some people have run into issues.

Digestive Discomfort

Too much malic acid may irritate the gut. Some folks report stomach pain, bloating, nausea, or even diarrhea after taking large amounts. The body can only handle so much acid, and concentrated doses tilt the stomach’s balance toward discomfort. A person with a sensitive stomach or underlying digestive disease will probably notice smaller amounts causing distress.

Oral Health Concerns

Dentists talk often about the dangers of acids for tooth enamel. Over time, sour candies—many relying on malic acid—can soften the enamel and set off tooth decay. Sipping acidic sodas or sucking on sour sweets exposes teeth to low pH for long stretches, wearing down the protective enamel. It’s not just malic acid at fault, but its tart punch certainly doesn’t help.

Possible Allergies and Rare Reactions

Allergic responses happen, but not frequently. Usually, these show up as tingling, hives, or itching after someone takes a supplement. The body sometimes flags new ingredients as threats, so anyone starting malic acid therapy for muscle pain or chronic fatigue should keep an eye out for strange rashes or swelling.

Experience from the Ground

I spent my childhood loving sour sweets, barely thinking about the science of flavor. As an adult, I needed dental work—much due to eroded enamel. My dentist told stories of teenagers flocking to tart-sprinkled candies and walking out with weakened teeth. I noticed a pattern: people with sensitive stomachs often had to cut back on high-acid foods. One friend who tried malic acid supplements for fibromyalgia ended up with cramps and gave up the experiment after a few days.

Supporting Claims with Science

Clinical research shows malic acid safe in normal dietary use. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists it as “generally recognized as safe” for foods. Still, research on long-term high-dose malic acid remains limited. Most side effects reported involve large, supplemental doses, not regular meals.

Practical Tips for Careful Use

People with digestive disorders, chronic tooth problems, or allergies should check with their doctor or dentist before starting malic acid supplements. Rinsing the mouth after acidic foods protects tooth enamel. Reading ingredient lists on sour snacks and drinks helps keep intake down. Instead of chasing cures with large doses, consider the range of whole fruits—which deliver malic acid alongside fiber, vitamins, and minerals in much gentler amounts.

Is Malic Acid suitable for vegans and vegetarians?

Malic Acid – A Closer Look

Malic acid pops up everywhere these days—fruit-flavored drinks, candies, even in vitamins on pharmacy shelves. People who try to live by clear ethics or keep animal products out of their diets often find themselves staring at long lists of ingredients, turning over labels and googling complicated names. Malic acid tends to spark questions. Is it plant-based or does it somehow involve animals?

How Malic Acid Is Made

The story starts in nature. Malic acid comes from fruits like apples and cherries. This sour compound gives green apples that sharp bite. Most commercial producers don’t press cargo containers full of orchard fruit though. They use chemicals like maleic anhydride, which usually traces back to petroleum sources or is synthesized from plant-based sugars using fermentation. The key point here is the process sidesteps animal products from start to finish.

Every time I’ve checked manufacturer FAQs or reviewed the FDA’s guidelines on food additives, the same answer shows up: malic acid, on its own, is vegan and vegetarian friendly. The starting ingredients in almost every country come from either synthetic or vegetable origins.

Why This Matters

Choosing safe food shouldn’t feel like detective work, but food companies use all sorts of additives, and some of them creep in from animal sources. For example, some red food colorings and a handful of amino acids can be animal-based. Making sense of it means looking at the supply chain with fresh eyes.

Smart advocacy for transparency relies on checking ingredient lists and researching where things come from. Most vegans or vegetarians I know share their findings in online groups or during grocery hauls because it saves hassle for others. Malic acid’s clear footprint makes life easier in that respect.

Watch Out for Blends and Coatings

Malic acid itself stays plant-based or petrochemically derived, but food science loves to complicate things. Take chewing gum or coated candies. Sometimes manufacturers add malic acid during the sugar-coating process. While malic acid isn’t the problem, the agent used to stick that tart coating might come from shellac (from insects) or include dairy-based glazes. For people looking to keep animal products off their plates, reading the whole label remains essential.

Nutritional supplements sometimes add malic acid to mask flavors or boost absorption, and the capsule or tablet itself could contain gelatin or other animal derivatives. Years of reading small print have taught me that “vegan” or “vegetarian” claims often settle the matter quickly.

Paths to More Clarity

Making strict dietary choices gets easier with clear labeling and honest supply chains. Organizations like The Vegan Society keep pressure on companies to label their products transparently. Encouraging routine third-party audits or certifications also helps. I’ve met plenty of folks over the years who stopped guessing and just pick brands with a visible commitment to vegan or vegetarian values, rather than rolling the dice with unlabeled items.

Education and asking good questions play the biggest role. If more consumers ask about what’s in their food, companies pay attention. Malic acid scores well for those who care about animal ingredients. The main thing to watch for is not the acid itself, but the other stuff sharing the label. Reading up, pressing companies for details, and supporting brands that share information openly—everyday choices move things forward.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-hydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Other names |

Apple acid Hydroxybutanedioic acid DL-Malic acid 2-Hydroxysuccinic acid Monohydroxysuccinic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmæl.ɪk ˈæs.ɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Hydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Other names |

Apple acid D-Malic acid Hydroxybutanedioic acid L-Malic acid DL-Malic acid 2-Hydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmælɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 6915-15-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 821840 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17896 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL682 |

| ChemSpider | 673 |

| DrugBank | DB01394 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 'SDS_VAR(100.007.274)' |

| EC Number | EC 200-293-7 |

| Gmelin Reference | 15723 |

| KEGG | C00149 |

| MeSH | D008307 |

| PubChem CID | 525 |

| RTECS number | OO5250000 |

| UNII | 817L1N4CKP |

| UN number | UN1789 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5027569 |

| CAS Number | 6915-15-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1720994 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:6650 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1407 |

| ChemSpider | 821 |

| DrugBank | DB01398 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard for Malic Acid: `"03e8e2c6-b7e0-48a0-abb5-2a69c84abe3d"` |

| EC Number | EC 200-293-7 |

| Gmelin Reference | 61349 |

| KEGG | C00149 |

| MeSH | D008285 |

| PubChem CID | 525 |

| RTECS number | OO4925000 |

| UNII | 817L1N4CKP |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID3023872 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O5 |

| Molar mass | 134.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.601 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| log P | -1.26 |

| Vapor pressure | 1.1E-7 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.40, 5.20 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.13 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -20.6×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.595 |

| Dipole moment | 3.12 D |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O5 |

| Molar mass | 134.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or nearly white, crystalline powder or granules |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.601 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Miscible |

| log P | -1.26 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: <0.1 hPa (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.40, 5.20 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 11.57 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -19.6·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.584 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 3.13 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 153.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -970.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1360.4 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 157.4 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -891.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | –1341 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA12 |

| ATC code | A16AX06 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-1-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 220 °C (428 °F) |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 1600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Malic Acid: 1,600 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | B0087 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 200 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | The REL (Recommended Exposure Limit) for Malic Acid is "5 mg/m³". |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-1-0 |

| Flash point | Flash point: 227°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 220 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3,200 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 1600 mg/kg (Rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | PD0875000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 200 ppm |

| REL (Recommended) | 3.0 g/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Succinic acid Fumaric acid Tartaric acid Maleic acid Citric acid Lactic acid |

| Related compounds |

Fumaric acid Maleic acid Succinic acid Tartaric acid |