L-Threonine: A Down-to-Earth Deep Dive

Historical Development

People first pulled L-Threonine out of protein almost a hundred years ago, right at the edge of what felt like the golden era of amino acid discovery. William Cumming Rose and his colleagues figured out the last piece in the essential amino acid puzzle, and it shook up how nutritionists built animal feed and human diets. Over decades, the growing animal farming industry kept asking for purer, cheaper sources, and that pressure led to commercial production scaling up. Fermentation took center stage as scientific wizards tamed bacteria such as Escherichia coli to churn out threonine from sugars. This slow shift from extraction to industrial biotechnology gave the world steady barrels of L-Threonine, helping everyone feed animals and, by extension, people.

Product Overview

L-Threonine stands tall among essential amino acids, which means animals can’t build it on their own. Feed companies grind it into powder or granules and toss it into livestock diets, filling the gaps left by ordinary grains, corn, and soybean meal. Bottles of it line lab shelves too, for cell culture and supplements. On the market, buyers often see “L-Threonine 98% Feed Grade” or “L-Threonine 99% Food Grade” marked plainly on bags headed to giant feed mills or pharmaceutical companies.

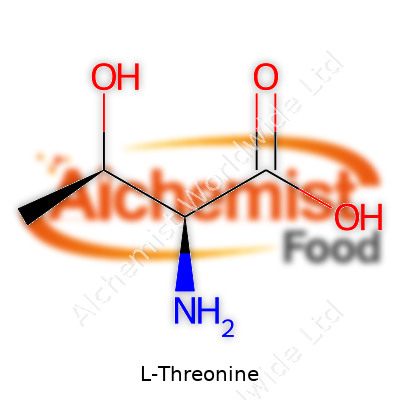

Physical & Chemical Properties

This amino acid looks almost like sugar—white, odorless crystals that melt when the heat goes past 250°C. It dissolves pretty well in water, and not much at all in ethanol or ether. Chemically, it goes by the formula C4H9NO3, blending an amine, a carboxyl group, a hydroxyl group, and a methyl. Because of its chiral carbon, L-Threonine has a sister called D-Threonine, but only the L-form fits into animal proteins, so they pay not a dime for D if they only raise livestock or produce supplements.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers need to back up every shipment with certificates. Specifics like moisture under 1%, heavy metals lower than 10 mg/kg, and absence of other amino acid contaminants dominate test sheets. Labels must stick to feed and food regulations, showing concentration (98% plus for feed, 99% for pharma), test methods, country of origin, and shelf life (often two years, sealed and dry). These specs make sure feed companies give animals what nutritionists design—not guesswork, just numbers and results.

Preparation Method

Old chemistry textbooks talk about protein hydrolysis with acids, but biotech took over since the 1980s. Bioreactors now pump out L-Threonine as E. coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum gorge themselves on sugars and oxygen—no sulfuric acid mess, just microbes doing their job for hours on end, spitting out threonine as they grow. Downstream, purification strips out unwanted amino acids and fermentation junk, leaving white crystals that head straight to animal feed plants. Fermentation not only raised yields but reduced byproducts, made energy use easier to control, and cut costs for farmers and factories.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

L-Threonine’s hydroxyl group opens up opportunities for chemists. They can swap groups, make esters, or protect the amine for peptide synthesis. In the lab, simple reactions like phosphorylation mimic protein signaling, and acetylation or methylation create analogs for medical or research use. These tricks let scientists map out enzymes or trace metabolic pathways, making threonine more than just a nutrition supplement.

Synonyms & Product Names

L-Threonine doesn’t hide under many names—sometimes labels show 2-Amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid or L-α-amino-β-hydroxybutyric acid, but most buyers stick to the plain “L-Threonine,” “Feed Grade Threonine,” or brand names tacked onto sacks leaving bioreactors or refineries. CAS Number 72-19-5 often helps buyers sift good sources from cheap fakes.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling L-Threonine brings little risk by itself. Workers stick to dust masks and gloves for big mixing jobs. Dust can irritate skin or eyes if clouds get out of control. Factories enforce cleanroom standards, traceability logbooks, and GMP frameworks, all designed to keep contamination away—nobody wants urea or heavy metals sneaking onto farm fields or into feed bins. Regulators in Europe or North America drop in for audits, checking that plants test their outputs, store everything dry, and stop any cross-contamination before it starts.

Application Area

Most of the L-Threonine sold heads straight to animal feed plants—pigs and poultry need threonine to build muscle, and when corn or soybean meal comes up short, diets stall growth. Supplementing diets leads to better feed conversion, less nitrogen runoff in manure, and leaner pork chops, a win-win for both farm margins and cleaner rivers. Outside farms, the same compound boosts cell cultures for biotech or biopharma factories, where threonine supports protein production for vaccines or enzymes. Some companies bottle pharmaceutical grade threonine for medical nutrition, treating short bowel syndrome or rare metabolic disorders, where every gram keeps patients healthier.

Research & Development

Nutrition researchers still run feeding trials, searching for the right ratios to boost protein yield in meat, milk, or eggs. Biotech companies engineer new strains of E. coli for fatter yields, less byproducts, or faster fermentation rates. Food scientists watch for new uses in vegan foods, where threonine could fill in nutritional gaps in plant protein. Academics tweak the structure of threonine, tacking on chemical groups for drug delivery or synthetic peptide research, always searching for new leads in antibiotics, immune modulators, or enzyme targets.

Toxicity Research

The body treats L-Threonine with respect in normal amounts, burning what it needs for protein and letting kidneys flush out the rest. High doses, way above natural intake from foods or supplemented feeds, sometimes lead to gut discomfort or metabolic upset, but dangerous toxicity pops up only with extreme misuse. Rats and pigs tolerate well-formulated diets, even with threonine spiked high above regular rations. Agencies keep watching for any sign of chronic toxicity or carcinogenicity, but so far, feeding trials and epidemiology say threonine ranks low on the risk charts.

Future Prospects

Growing demand for animal protein keeps L-Threonine front and center for feed makers aiming to slash costs, cut nitrogen pollution, and raise healthy herds. Improved fermentation technology keeps dropping prices and energy needs, letting developing countries grab bigger market share. Synthetic biology may soon put custom threonine analogs into drug pipelines, aiming for better medicines that imitate or block natural pathways. As plant-based and lab-grown protein pick up steam, threonine will stay in the mix, closing nutritional gaps for both animals and humans. Regulatory pressures may only get tighter, with more countries setting stricter limits on contaminants and demanding cleaner product streams—producers who stay ahead with transparent traceability and robust testing will ride the next wave.

What is L-Threonine used for?

Amino Acids and Animal Diets

L-Threonine pops up often in the world of nutrition, especially among livestock specialists and people who care deeply about the food chain. As an amino acid, it works as a key player in building the proteins animals rely on for growth and repair. Many years back, big operations in the agriculture sector noticed that their animals weren’t growing as quickly as possible, or were burning through more feed to reach weight targets. This led to careful tracking of the nutrients in feeds and revealed something important: corn and soybeans, which form the backbone of many commercial feeds, come up short on some essential amino acids, threonine being near the top of that list.

Adding L-Threonine to animal feed isn’t just about speeding up growth. This choice means more precise feeding, less leftover nitrogen, and better results for both animals and producers. The numbers back this up. In poultry farming, for instance, supplementing with L-Threonine can improve weight gain and feed conversion by about 5–10%. It also cuts down on ammonia emissions in manure, which is something I’ve noticed benefits not just the farms, but whole communities downwind of poultry barns.

L-Threonine in Human Health

People might not talk about threonine as much as protein powders or vitamins, but it shapes human health in quiet ways all the same. Adults with a balanced diet usually get enough from foods like cottage cheese, lentils, or eggs. The body leans on threonine for strong muscles, a working immune system, and a healthy liver. For those who face restricted diets—older family members or anyone suffering from malabsorption—supplements sometimes fill the gap, under careful supervision. Research points out that threonine also helps manage certain gut conditions, thanks to its role in building mucins that line and defend the intestine.

Environmental and Economic Impacts

By targeting threonine deficiencies, feed producers can use less protein overall. It’s a practical approach that helps keep costs under control. Less protein means less land and fewer resources needed to grow that protein in the first place. The ripple effect stretches beyond just animal health—farmers and suppliers both stand to save money, and the ecosystem gets a break from excess nitrogen runoff.

This solution doesn’t stand alone. L-Threonine works alongside other amino acids like lysine and methionine for best results. Feed formulators need tools like near-infrared spectroscopy and careful mixing strategies to make sure each bag of feed delivers what it promises. I’ve seen firsthand that this detailed work pays off, leading to more resilient herds and flocks.

Quality and Trust Matter

Like any nutritional supplement, not all L-Threonine is created equal. Feed mills and food companies often choose suppliers with strong records of safety, consistent testing, and traceability. Regulatory agencies in the United States and Europe keep a close eye on purity, labeling, and sourcing. These guardrails protect animal and human health, and keep trust intact up and down the supply chain.

L-Threonine isn’t just another ingredient—it’s a reminder that details matter in nutrition. Every small nutrient can tip the balance toward better health, better economics, and less stress on the environment. After years of working in both agriculture and wellness spaces, it’s clear that understanding ingredients like threonine gives producers and consumers more power—and more confidence—at every meal.

Is L-Threonine safe to take daily?

Understanding L-Threonine’s Role in Health

L-Threonine belongs in every conversation about amino acids that support basic health. As an essential amino acid, the body depends on L-Threonine for everything from muscle recovery to immune function. Food sources like fish, chicken, lentils, and eggs provide L-Threonine every day, and most people get enough if protein intake meets daily requirements. There’s been buzz about supplements, usually marketed to athletes and people dealing with muscle loss.

The Science and Safety Behind L-Threonine Supplements

Solid, peer-reviewed research says that L-Threonine does not build up in the body. Normal kidneys filter out what you do not use, and that means a low risk for most healthy adults. Clinical studies often use doses from 250 mg to 1,500 mg a day—levels much higher than found in a daily serving of meat or beans. In those studies, regular users reported few, if any, unwanted effects.

Taking mega-doses without a doctor’s input brings risks, just like loading up on other single amino acids. Veterinary medicine shows that very high doses, out of line with a balanced diet, sometimes stress the liver or kidneys in animals. In people already living with kidney or liver conditions, extra amino acids add unnecessary strain.

Daily Use: Who Stands to Benefit—or Not

Athletes sometimes look for an edge with extra L-Threonine, hoping for better recovery or muscle growth. People following a strict vegan diet, dealing with digestive disorders, or recovering from injury may find supplementation fills in gaps from food. On the other hand, most adults eating a protein-rich diet rarely see measurable differences from extra L-Threonine.

Safety reviews from government agencies and organizations like the EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) recognize that L-Threonine appears safe at standard supplement doses. No evidence links normal, daily use to serious harm in healthy users. Overuse or unnecessary stacking with other supplements invites trouble—especially for those with medical issues.

Trusted Sources and Label Transparency Matter

Supplement quality varies wildly, so choosing trusted brands with third-party testing counts for a lot. I learned this lesson after a handful of poorly regulated supplements led to stomach issues and unreliable results. Serious brands give clear dosing, avoid hidden fillers, and update their labels when new research comes out.

Two friends started taking L-Threonine during heavy training cycles last year. One bought a reputable product, the other went bargain hunting on imported websites. The former never had an issue; the latter experienced nausea and stopped after a week. Trusted brands with proper labels protect you from accidental overdoses or contaminants.

Making the Call: Self-Awareness and Medical Advice

Most bodies handle L-Threonine just fine in doses up to 1,500 mg, especially for those supplementing because of increased physical demands. People with allergies, rare metabolic disorders, or organ disease face a different risk, so they should always talk shop with their doctor. No magic bullet exists in nutrition—getting enough amino acids from a variety of foods works best for most. Supplementing L-Threonine only makes sense when real-world needs or medical advice point in that direction.

What are the benefits of L-Threonine supplementation?

Why People Care About L-Threonine

I’ve noticed more people chatting about amino acids lately, especially those who pay attention to what goes in their food and how their bodies feel after meals. L-Threonine, one of the essential amino acids, lands on the radar because the body can’t create it by itself. You have to put it in your body through food or supplements. Foods like cottage cheese, lentils, and poultry give a decent amount, but not everyone gets those things every day. So, where does a supplement fit in?

How L-Threonine Contributes to Daily Health

There’s real science behind why folks pay attention to threonine. Your body uses it to form proteins. That’s a basic need, whether you’re trying to build muscle, keep your immune system firing strong, or help your liver break down toxins. What the research tells us is that threonine acts as a building block for substances like collagen and elastin—without those, skin and joints pay the price.

Supporting evidence from journals like Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care suggests that a steady source of threonine benefits gut health, particularly the mucous lining in your intestines. That lining acts as a shield for digestion and protection against unwanted bacteria. People who get enough threonine in their diet or through supplements tend to report fewer gut irritations. It also appears to help keep your immune system alert by supporting production of antibodies.

Useful for Different Walks of Life

In my daily life, I've seen athletes and vegetarians both turn to L-Threonine. Athletes strain muscles, and recovery isn’t just about rest. Amino acids matter. A 2022 review in Nutrients highlighted that low threonine slows muscle repair, which can stall progress. Vegetarian diets sometimes fall short on threonine since plant proteins often come up with lower levels of essential amino acids. Supplementation, in these cases, fills the gap without tossing in a lot of extra calories or animal protein.

There are also people with specific medical needs—like those with certain metabolic disorders—who can benefit when a doctor prescribes threonine. Research following children with conditions like spasticity suggests that supplementation may reduce symptoms and support motor function.

Looking at the Bigger Picture and Safer Use

Most people don’t feel L-Threonine working immediately—no burst of energy or magical weight loss effect. Its influence builds quietly, showing in smoother digestion, steadier recovery after workouts, or fewer common colds through winter. For folks considering supplements, it makes sense to look at the facts: the recommended dietary intake for adults falls in the 0.5 to 1 gram per day range, and most quality supplements respect this window. Exceeding these amounts brings risks, including stomach upset or imbalance with other amino acids.

Decisions about adding any supplement should start with an honest look at what you eat and how you feel. Some people may see no benefit if their diet covers all the bases. The best approach: ask a health professional, preferably someone who knows your nutrition and medical profile. Labels like “pharmaceutical grade” or brands registered with third-party testing can give peace of mind that what’s on the label matches what’s inside the bottle.

Improving Access and Understanding

People get more out of supplements like L-Threonine with clear, trustworthy education. Doctors, registered dietitians, and credible online health resources owe it to users to provide honest facts and cut through hype. Easy access to blood tests and consultations also helps identify anyone truly missing essential amino acids. More community-based nutrition programs and transparent product labeling would go a long way toward helping everyone make sound choices about adding L-Threonine—or anything else—to their daily routine.

Are there any side effects of taking L-Threonine?

Understanding L-Threonine and Daily Health

L-Threonine has drawn plenty of attention, mainly in health and fitness spaces. This amino acid shows up naturally in foods like meat, cheese, and leafy greens. Folks reach for supplements, hoping for better muscle recovery, improved liver function, or maybe some support with stress. Hearing about another supplement can make you wonder if it’s a smart addition to your routine—or if you’re just swallowing hype.

Experiences Shared and Side Effects Observed

I’ve watched people take L-Threonine for months—friends at the gym, people in online forums, family members who swear by amino acid blends. Most stick to doses around 500-1000 mg per day. They usually report that nothing dramatic happens. No one expects dramatic changes, either, but that mundane experience is telling. Science backs this up: research published in “Nutrition & Metabolism” suggests L-Threonine is safe in moderate amounts, especially when you get it from your food.

Go overboard, though, and things start to shift. A handful of studies show that higher doses—doses much higher than what you’d get from a varied diet—open the door to some nagging issues. I’ve seen people mention mild stomach upset. Others talk about headaches or a jittery feeling. The published data are limited, but reports usually sound like the usual effects from pushing beyond what the body actually needs. Too much of anything—even an amino acid—can bother your digestive tract or crank up your nervous system.

If you struggle with kidney or liver conditions, talk with a healthcare provider first. These organs process amino acids, and any supplement adds to their workload. Medical professionals flag this as a risk for patients with chronic kidney disease. There’s no point making things tougher for your organs when regular food sources do the job.

Spotting the Real Risks Versus the Hype

It’s easy to fall into the supplement trap. I’ve noticed people assume “natural” equals “risk-free,” but nature doesn’t always hand out passes. While regular dietary intake of threonine hasn’t shown problems, pill form concentrates the dose. The FDA hasn’t issued firm warnings about L-Threonine because evidence points to low risk, not no risk.

Teenagers or pregnant women might feel curious about adding supplements. For these groups, sticking with whole foods always makes more sense. Any added threonine beyond what food provides just has not been tested enough in these populations. My advice echoes what doctors say: don’t gamble on something you don’t need.

Ways to Use L-Threonine Safely

If you’re thinking about threonine for a health boost, start with your plate, not a bottle. Eggs, fish, lean meats, and nuts cover any reasonable requirement. Supplements sometimes fit certain health conditions, like some rare genetic disorders, but these cases need a doctor’s guidance. Following guidelines from the National Institutes of Health, there’s no solid reason for most people to go above a regular intake through diet.

Listen to your body. If you try a supplement and feel off—nausea, headaches, or anything unusual—it’s time to stop. Side effects serve as warnings. Keep your healthcare provider in the loop anytime you start or stop a supplement. That decision keeps you safe in a market crowded by products with big promises, but not many guarantees.

Pulling It All Together

Choosing supplements always carries a bit of uncertainty. L-Threonine, in normal amounts from real food, rarely raises alarm bells. Pushing past that, especially without real need or solid advice, tips the balance from healthy curiosity to unnecessary risk. Focus on balanced meals and save the pills for situations that call for a little extra—backed by a professional’s word, not just a hunch or an ad.

What is the recommended dosage for L-Threonine?

Understanding L-Threonine and Its Place in Nutrition

L-Threonine often comes up for folks interested in amino acids, muscle recovery, and sometimes even immune support. This amino acid helps build protein and supports a bunch of body functions, including the health of your gut lining and central nervous system. Doctors and nutritionists recognize its role in everyday health, so interest in L-Threonine supplements keeps growing.

Typical Dosage Ranges People Use

L-Threonine naturally shows up in everyday foods like eggs, cottage cheese, fish, and lentils. If your diet includes those foods, you’re already getting a solid base of threonine. For adults, a typical dietary intake hits around 500 to 1,000 mg each day from meals alone. People using threonine as a supplement often target higher amounts—most reputable clinical studies on L-Threonine stick to 500 mg to 1,000 mg per dose, usually taken once or twice per day.

Some supplement guides and amino acid-focused products go a bit higher, sometimes up to 2,000 mg daily, split into two or three servings. Athletes or those with specific metabolic needs ask if doses higher than that could do more, but studies rarely test much above this range for basic supplementation.

Evidence and Safety: Facts Matter

High-dose threonine therapy (doses over 4,000 mg daily) occasionally appears in medical studies related to neurological disorders or metabolic challenges. In these cases, medical professionals watch for problems and adjust dosages carefully. For most adults just aiming for general wellness, sticking to 500–2,000 mg daily aligns with established safety data. The FDA labels L-Threonine as “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) when consumed in typical dietary amounts.

Personal experience has taught me the value of checking for potential side effects, too. Going beyond what your body can handle brings risks—nausea or digestive unrest often signal that a supplement dose pushes boundaries. One study published in the “Journal of Nutrition” highlights no extra benefit—and more risk—at levels over the usual dietary range for most people.

Who May Benefit (and Who Should Avoid)

Not everyone needs to supplement threonine. Folks already eating balanced diets with enough complete protein get what they need. Vegetarians or vegans sometimes ask if they’re in danger of low L-Threonine, but most plant-rich diets still cover the minimum. Risks may show up for people with metabolic conditions or kidney trouble. Anyone with chronic disease or using medication should talk to a professional before adding L-Threonine to their routine, especially in supplement form.

Improving Access to Reliable Information

One major barrier to responsible amino acid use comes from inconsistent supplement labeling and exaggerated marketing claims. Third-party certification, batch-level purity checks, and transparent sourcing help weed out low-quality products. Making these standards clear helps consumers avoid unintentional overdosing or contaminants.

Doctors and nutritionists need easy access to up-to-date studies and patient tools, too. Bringing trustworthy dosage recommendations into clinics and into everyday health conversations keeps people safe and informed. Anyone considering higher doses or ongoing use for health conditions reaps the most benefit from regular medical check-ins, basic bloodwork, and open dialogue about what actually works.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2S,3R)-2-Amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid |

| Other names |

2-Amino-3-hydroxybutyric acid Threonine |

| Pronunciation | /ɛl ˈθriː.əˌniːn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2S,3R)-2-amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid |

| Other names |

(2S,3R)-2-Amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid Threonine |

| Pronunciation | /ɛlˈθriː.ə.niːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 72-19-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/ajax/php/jsmol.php?modelid=885&lang=en` |

| Beilstein Reference | 136963 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16899 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL12324 |

| ChemSpider | 73056 |

| DrugBank | DB00150 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.047.520 |

| EC Number | 2.2.1.6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 71338 |

| KEGG | C00188 |

| MeSH | D001937 |

| PubChem CID | 6288 |

| RTECS number | XP2100000 |

| UNII | 9F8EIK7A5T |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 72-19-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3D model (JSmol)` string for **L-Threonine**: ``` 33709 ``` This is the JSmol 3D model ID for L-Threonine. |

| Beilstein Reference | 1718737 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16857 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL418 |

| ChemSpider | 797 |

| DrugBank | DB00160 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.387 |

| EC Number | EC 200-774-1 |

| Gmelin Reference | 7784 |

| KEGG | C00188 |

| MeSH | D001937 |

| PubChem CID | 6288 |

| RTECS number | XP7320000 |

| UNII | 9L3D0I5EMK |

| UN number | UN1848 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C4H9NO3 |

| Molar mass | 119.12 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.90 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -2.6 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.09 (carboxyl), 9.10 (amino) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.96 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.6×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.536 |

| Dipole moment | 4.21 D |

| Chemical formula | C4H9NO3 |

| Molar mass | 119.12 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.3 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -3.22 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.09, 9.10 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.96 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.6×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.537 |

| Dipole moment | 2.7851 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 110.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -889.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1380.2 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 98.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -951.1 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1464 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA11 |

| ATC code | A16AA04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P261, P264, P271, P272, P273, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313, P362+P364, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 400°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ oral rat: >5,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat LD50 > 5,000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SR7510000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | L-Threonine 2.0% |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Exclamation mark |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid breathing dust. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use with adequate ventilation. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 400°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ (oral, rat): > 5,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (Oral, Rat): 9000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SKL783 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 3 g |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Threonine Allothreonine Methionine Serine Isoleucine |

| Related compounds |

D-threonine Allothreonine Isoleucine Serine Glycine |