L-Lysine Hydrochloride: From Discovery to Future Horizons

Historical Development

Researchers first identified lysine in the late nineteenth century, isolating it from casein found in milk. At the time, food production didn’t focus much on amino acid profiles. Only later, with the rapid expansion of animal agriculture and changing dietary habits worldwide, did the search for nutrient supplements intensify. By the 1970s, commercial-scale production ramped up as fermentation technology caught up with demand. Chemists and biologists harnessed microbial fermentation processes, optimizing strains of Corynebacterium glutamicum and Escherichia coli. Growing up in a country that relies heavily on both livestock and poultry, I’ve seen local industries transform overnight, often crediting amino acid supplementation for better productivity and overall animal health. L-Lysine Hydrochloride soon became as common in animal feed as salt in a home pantry, changing economic landscapes and diets across entire continents.

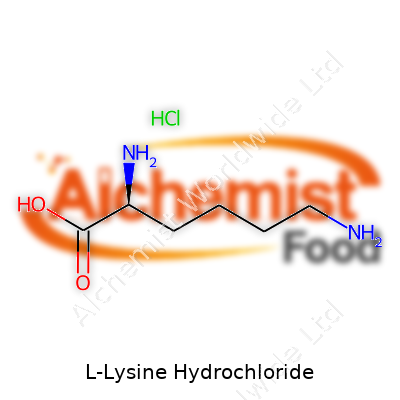

Product Overview

L-Lysine Hydrochloride comes as a pale, odorless crystalline powder. On the manufacturing side, companies usually market this supplement for its high lysine purity content—every batch often reaches above 98 percent. Among amino acids, lysine stands out for supporting protein synthesis and improving animal weight gain. Demand keeps surging in regions where diets rely on cereal crops, which often lack adequate lysine levels. In my own experience working on farms, adding lysine transforms the way animals grow—muscle development improves and overall health stabilizes, even in challenging environments.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Chemically, L-Lysine Hydrochloride carries the formula C6H14N2O2·HCl and a molecular weight of about 182.65 g/mol. It dissolves well in water, which matters most for feed manufacturers mixing large batches in liquid form. Other solvents don’t break it down, so water remains the industry standard. Physically, the substance resists melting at everyday temperatures, holding up well during transport or storage. For anyone managing warehouse inventories or shipping logistics, this kind of stability smooths out many headaches.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Regulators and customers expect clear documentation on amino acid supplements. Quality control programs regularly test for lysine content, moisture level, and the presence of heavy metals or contaminants. L-Lysine Hydrochloride intended for feed usually comes labeled with a minimum purity—often at or above 98.5%. Labels also show batch numbers, expiry dates, country of origin, and recommended storage conditions. On visits to feed mills, I’ve seen how strict documentation standards help prevent mix-ups and assure nutritionists they’re getting exactly what they order.

Preparation Method

Modern production involves microbial fermentation, where genetically optimized bacteria convert carbohydrates or molasses into lysine. The process involves culturing these microbes in large fermenters, controlling pH, oxygen, and temperature at every stage. Fermentation broth then passes through several refining stages—centrifugation, filtration, concentration, and crystallization. Lysine separates and combines with hydrochloric acid to yield the final hydrochloride salt. From managing bioreactor runs, I learned efficiency hinges not on sophisticated machines, but on precise input control and hands-on monitoring.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Lysine’s structure, with its additional amino group, enables chemical modifications not possible with all amino acids. It undergoes acylation, oxidation, and methylation to create various derivatives for research and pharmaceutical use. In the body, this same reactive group plays a role in cross-linking collagen and forming complex proteins. Innovators keep exploring these chemical tricks to develop new biomaterials and functional foods; chemists often refer back to lysine’s role in protein crosslinking and gene regulation during their experiments.

Synonyms & Product Names

On the market, L-Lysine Hydrochloride goes by multiple names: Lysine Monohydrochloride, Lys.HCl, and even E640. Some refer to it by the European Food Additives number. In research literature or commercial catalogs, you might find it under the CAS number 657-27-2. Such diversity in naming sometimes confuses newcomers, but for experienced buyers and suppliers, identifying genuine product always comes down to detailed documentation.

Safety & Operational Standards

Workplaces handling L-Lysine Hydrochloride must follow stringent safety protocols due to dust formation and occasional respiratory irritation. Industries typically provide masks, gloves, and well-ventilated workspace for operators managing large-volume mixing and packaging. According to occupational health guidelines and my own experience in feed mills, proper staff training and adherence to safety data sheets prevent accidents. Storage requires keeping the powder dry, away from contaminants, and avoiding prolonged exposure to sunlight or moisture which could degrade the product.

Application Area

The largest application, by far, lies in animal nutrition. Supplementing lysine in pig, poultry, and fish diets bridges nutritional gaps in corn and wheat-heavy feeds. Using these mixtures daily, farmers report faster growth rates, better feed efficiency, higher lean meat percentages, and improved reproductive outcomes. Nutritionists working with human health also use pharmaceutical-grade lysine to formulate dietary supplements, treat herpes simplex infections, and aid tissue repair. Some food manufacturers even add the amino acid to fortify bread and cereals, although regulations and public awareness still lag behind animal feed industries in several countries.

Research & Development

Innovation continues as scientists tweak both microbial strains and fermentation methods to squeeze more product out of each run. Research teams now focus on metabolic engineering—rewiring bacteria or yeast to boost yield while minimizing waste byproducts. Quality control technologies keep growing more sophisticated, using real-time sensors and chromatographic techniques. Trials keep pushing lysine’s boundaries—studying how it might improve immune responses or support cognitive health. Any new discovery often sparks a ripple effect through agriculture, food science, and even pharmaceuticals.

Toxicity Research

Extensive toxicity studies show that lysine remains safe for most species at recommended levels, although over-supplementation can cause digestive discomfort or metabolic issues in some cases. Regulatory agencies rely on these studies to set maximum allowable levels for both animal feed and human supplements. During my own fieldwork, I’ve witnessed veterinarians monitor herds for signs of overuse, reminding everyone that even beneficial nutrients require balance. Chronic exposure to dust raises some occupational health concerns, reinforcing the need for personal protective equipment in processing plants.

Future Prospects

Demand for sustainable protein sources drives the lysine hydrochloride industry to expand and diversify. As more countries shift toward plant-based diets or explore lab-grown meats, the need for precision amino acid supplementation only grows. Biotechnology firms continue pushing microbial fermentation efficiency, reducing both costs and environmental impact. On the other side, regulatory frameworks, particularly in emerging economies, have started adapting to safeguard feed and food quality. Public education and transparent labeling will matter more; people have become much more conscious of what enters the food chain. Watching these developments, I see a global food system increasingly shaped by science-driven nutritional solutions like L-Lysine Hydrochloride.

What is L-Lysine Hydrochloride used for?

Why L-Lysine Hydrochloride Matters

Walk down any farm aisle or talk to anyone raising animals, and it won’t take long before L-Lysine Hydrochloride comes up. It’s an amino acid, and it plays a key role in animal nutrition. Chickens, pigs, dairy cows: just about any animal meant for food or milk relies on lysine as part of their diet. Unlike crops where traditional fertilizer does the heavy lifting, animals can’t produce lysine in their bodies. They need it from food, and sometimes the stuff found in corn or soybean meal doesn’t cut it. So farmers add lysine in its hydrochloride form to make sure animals grow efficiently.

Boosting Animal Health and Production

Several years back, I visited a friend’s pig farm outside Des Moines. He mixed lysine right into the feed, and his pigs put on more lean muscle and less fat compared to farms that skipped supplementation. That mattered in terms of profit margins and also animal well-being. Scientific findings back this up. Research from Iowa State University shows supplemental lysine helps pigs convert feed into muscle instead of just body fat. The result? More pork, same amount of grain—less waste from an environmental standpoint.

Dairy and poultry sectors get similar benefits. Dairy cows with adequate lysine produce more milk. Chickens build stronger, healthier frames. For farms trying to balance cost with output, missing out on lysine just doesn’t pencil out.

Beyond the Barn: L-Lysine Hydrochloride for People

The story doesn’t stop with animal feed. Lysine finds a place in some human nutrition products. People with diets low in protein sometimes struggle to get enough lysine from food alone. It’s a building block for muscles, skin, enzymes—you name it. Lysine hydrochloride turns up in dietary supplements and, for some who can’t swallow pills, in powder blended into drinks.

Health professionals sometimes mention lysine for people who struggle with frequent cold sores. There’s clinical evidence showing it can cut down the duration and intensity, when used at higher doses for short periods. It’s never about miracle cures, but it’s one more tool for managing everyday health concerns without heavy medication.

Concerns and Practical Solutions

No product comes without issues. An overreliance on lysine supplements in animal agriculture links back to how we grow and feed animals on a large scale. Overdoing any supplement can throw off balance, affecting everything from kidney health in livestock to costs for small farmers. For people, taking massive doses of lysine from over-the-counter products can cause stomach issues or, in rare cases, affect how kidneys process nutrients.

Listening to vets and nutritionists makes the difference. They use feed testing and animal health checks to spot shortages before problems set in. Small-scale farmers near me swap stories and strategies on how to use less soy, more local grains, and only supplement lysine for actual shortages backed by numbers.

Moving Forward

Innovation in fermentation technology now enables large-scale lysine production using sustainable raw materials instead of old-school chemical synthesis. This cuts industrial waste and works better for producers designing mixes tailored to regional crops. For ordinary people, having access to credible nutrition advice and high-quality products keeps the focus on health, not hype.

Is L-Lysine Hydrochloride safe for daily consumption?

Understanding L-Lysine Hydrochloride

L-Lysine hydrochloride shows up in the world of amino acid supplements and animal feed pretty often. This isn’t an exotic new compound—it’s just the hydrochloride form of L-lysine, an essential amino acid that human bodies rely on for things like protein synthesis and tissue repair. Because our bodies can’t make lysine, we get it mostly from food: dairy, meat, fish, and some beans. Supplementing with L-lysine hydrochloride just pushes levels higher, filling gaps when diet alone falls short.

Safety and Human Health

Plenty of research circles around the safety question, and my time digging into these studies has always pointed out one thing: for most healthy adults, taking L-lysine hydrochloride in reasonable doses rarely causes trouble. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes this form as generally safe (GRAS) for use in foods and supplements. The World Health Organization marks the recommended daily lysine intake at about 30 mg per kilogram of body weight—roughly 2 grams for an average adult.

At higher supplement levels, a small slice of people might experience gut discomfort—nausea, stomach cramps, or diarrhea—but these reports remain rare. Still, someone with kidney issues or chronic diseases should check with a health professional before reaching for the supplement bottle. The kidneys handle excess amino acids, and chronic overconsumption could pile up stress. I’ve seen advice that folks with severe liver or renal conditions steer clear, sticking to food-based sources instead.

Looking at Long-Term Consumption

Amino acid supplements drift in and out of popularity. My curiosity about their long-term impact led me to large-scale studies on populations supplementing lysine for months at a time. Key findings? For people in good health, lysine hydrochloride doesn’t show signs of long-term adverse effects at typical supplement doses (up to 3 grams daily). The human body seems pretty good at dealing with manageable extra amounts. In rare cases, massive overdoses above 10 grams a day could trigger toxic symptoms—just like unloading any single nutrient in the body.

The hydrochloride salt makes the amino acid more stable, but the HCl component adds nothing dangerous at low levels. Stomach acid is already made from hydrochloric acid, and supplement sizes don’t come close to what the gut deals with naturally.

Sourcing and Purity

One real concern pops up around product quality. Not all supplements use pharmaceutical-grade ingredients. Food scientists and supplement experts recommend picking products from brands with solid third-party testing and clear supply chain transparency. Contaminants—heavy metals, toxins, even the wrong isomers—sometimes sneak in when manufacturers cut corners. I check for NSF or USP certifications and avoid anything that hides behind proprietary blends with no dosage listed.

Making L-Lysine Hydrochloride Work for You

For most adults without kidney or liver disease, daily L-lysine hydrochloride in moderate amounts poses little risk. Some athletes and plant-based eaters use it to balance out protein intake, making sure they’re not missing this essential amino acid. Focus on a balanced diet, and think of supplements as a back-up plan rather than your main source.

Talk with a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement. The right conversation can prevent mistakes you don’t want to make, especially for those on medication or managing chronic conditions. Knowledge matters with supplements; rushing in on your own can be a recipe for wasted money or unnecessary risk.

What are the side effects of L-Lysine Hydrochloride?

L-Lysine and Its Uses

L-Lysine Hydrochloride often finds its way into everyday supplements, animal feeds, and even sports nutrition routines. As an amino acid, lysine plays a role in building protein and supporting body functions most of us take for granted. I’ve known people who reach for lysine during cold sore outbreaks. It’s also a staple in the livestock industry, where it acts as a feed additive to support growth. Since lysine isn’t produced naturally in the body, diet and supplementation remain the main sources.

Digestive Upsets: The Most Common Complaint

After talking to people in nutrition groups and going through clinical references, the most common downside becomes clear pretty quickly: digestive upset. Nausea, stomach pain, and diarrhea can show up, especially if someone takes more than is recommended. Research in the Journal of Nutrition identifies these discomforts at high doses but notes that mild upset tends to resolve if the supplement is stopped or cut back. I’ve seen folks ignore serving instructions, figuring more means better, only to end up sidelined by cramps or bloating. The body only absorbs so much lysine at once.

Kidney Stress in Certain Situations

Lysine can put pressure on kidneys, especially for anyone living with kidney disease or limited kidney function. Protein metabolism produces waste, and lysine, like any amino acid, can increase that load. The National Kidney Foundation points out that extra amino acids in supplements can lead to more waste products, which sick kidneys handle poorly. From my experience working with individuals on restricted diets, a conversation with a health professional always precedes new supplements, as kidney stress is nothing to roll the dice on.

Allergic and Sensitivity Reactions

Rarely, some people report sensitivity after lysine intake. This can include rash, itching, or swelling. While allergic reactions remain uncommon, reading ingredient lists carefully matters, especially with supplements sourced from different countries. I remember helping a friend comb through pill bottles after a breakout. It turned out, the additive in the lysine was the culprit—not lysine itself, but that scare highlights the value of buying from trusted sources and keeping an eye out for contamination.

Possible Calcium Interaction

Some studies suggest prolonged lysine use may boost calcium absorption in the gut. Researchers at Harvard Medical School found no direct cause for alarm, but high calcium levels can lead to their own problems—kidney stones, muscle aches, and even irregular heart rhythms if left unchecked. Folks prone to kidney stones may want to steer clear of extra lysine or at least check in with a doctor before adding it to the daily mix.

Practical Steps for Safe Use

Staying safe with lysine supplements comes down to routine habits: follow label directions, get supplements from reliable brands, and talk to your doctor if you have health conditions or take medication. Don’t double up on doses hoping for faster results; patience and moderation keep side effects in check. If digestive troubles, rashes, or any new symptoms appear, stop supplementing and reach out for advice. Reputable companies will answer questions about what's really in their products, and sharing experiences with other users can help spot problems early.

How should L-Lysine Hydrochloride be stored?

Safe Storage Protects Purity

L-Lysine Hydrochloride often gets tapped for its role in animal nutrition and food production, yet toss it on a shelf with any old product and risk losing its quality quick. Think about storing your favorite coffee—if you leave the bag open or let moisture sneak in, the rich flavor disappears. L-Lysine Hydrochloride acts the same way; exposure to the wrong environment cuts its shelf life and messes with the potency you count on.

Keep Moisture and Heat Out

Moist air and high temperature kick off trouble for this amino acid. The compound pulls in water fast, turning clumpy and sticky, which transforms a once-free-flowing powder into a paste that’s tough to measure and mix. Once moisture settles in, unwanted reactions start, leading to loss of nutritional value and spoilage. I’ve seen bags left open in hot, humid warehouses turn unusable in just a few days, wasting both time and money.

A cool, dry storeroom is your best friend here. Aim for temperatures under 25°C (77°F). Humidity should not go above 60%, which can usually be managed with a dehumidifier or air conditioning, depending on your climate. Direct sunlight hikes up the temperature inside packaging and speeds up chemical changes. In short, keep the product in the dark, as you would with oil or flour.

Original Packaging Matters

Original, sealed bags prevent contamination from bugs, dust, and other chemicals drifting around a storeroom. Cutting corners by scooping out handfuls for easy access lets contaminants sneak in, which ruins purity. I’ve heard of whole batches dumped after only a few days exposed to strong-smelling products stored nearby. L-Lysine Hydrochloride picks up odors and even tastes from cleaning agents or agricultural chemicals. That’s not only wasteful, it could create problems upstream in food or feed production.

Labeling and First-In, First-Out

Mark bags clearly with the date received and date opened. This step keeps older stock up front, making sure everything gets used before expiry. Ignoring this simple task opens the door to accidental cross-contamination and lost traceability. Disorganized storerooms breed mistakes, and lost batches can impact not just a single operation, but also larger supply chains. Attention to labeling protects everyone involved.

Avoid Direct Contact with Floor and Walls

Stacking bags right on the floor or pressed against walls leads to condensation, especially if temperatures swing at night. Moisture seeps in through the smallest pinhole or weak seam. Simple pallets or shelving lift bags up, keep air flowing, and cut down on dampness. I’ve watched the difference wooden pallets make—bags stored off the ground stay dry and clump-free week after week, compared to those sitting against cool concrete floors.

Train Staff for Consistency

Everyone who comes in contact with L-Lysine Hydrochloride should understand the rules. One careless worker who leaves a bag open or stacks heavy boxes can break seals and start spoilage. Quick, clear training with visual reminders helps teams stick to the process. It’s not just about rules; it’s about protecting both money and health, with minimal fuss.

Smart Storage Saves Money

Controlled storage of L-Lysine Hydrochloride often gets overlooked, but proper conditions guarantee every gram gets used for its intended purpose. Maintaining cool, dry, and clean storage means less waste, fewer recalls, and better end products. Investments in proper training, temperature control, and clear labeling pay for themselves by helping maintain product quality from arrival to use.

Can L-Lysine Hydrochloride interact with other medications?

Explaining L-Lysine Hydrochloride

L-Lysine Hydrochloride often shows up in conversations about supplements. Some people reach for it to support healthy growth or to ward off cold sores. Others see it as a useful addition in specific diets. This compound is a form of the amino acid lysine, important for body tissue repair and nutrient absorption. With all these benefits talked about, it makes sense to ask about possible risks, especially interactions with medications.

What Happens When Medicines Mix?

People often pile up supplements on top of prescription pills, thinking they’re harmless, but bodies can respond in unexpected ways. Some drugs need amino acids for absorption, which means a big dose of L-Lysine Hydrochloride can push or pull medicines through the system differently. Several years working in pharmacy taught me that supplements, while popular, can complicate a patient’s pill plan.

For example, antibiotics like gentamicin get processed through the kidneys. Bulking up on high amounts of lysine may stress the kidneys further or change how gentamicin works, according to data from the National Institutes of Health. The risk sounds low if you’re healthy, but risks rise for patients already dealing with kidney concerns. Speaking from long afternoons at the pharmacy counter, folks managing kidney issues already juggle a lot, and one wrong combination can bring unwelcome side effects.

Spotting Interactions With Seizure Medications

Another group of medicines to watch is anticonvulsants for epilepsy and mood disorders. Some evidence suggests that lysine can ramp up the side effects of certain drugs designed to quiet the nervous system. There's no broad warning label yet, but small studies and anecdotes from my days as a medical writer point toward a need for caution. When a patient came in complaining about dizziness and confusion after starting a lysine regimen on top of their medication, we dug in to check interactions, and sure enough, there was a strong possibility.

Calcium Absorption, Bones, and Supplements

Lysine helps bodies hold on to calcium, which most people see as a positive. Boosting calcium absorption builds stronger bones, especially as people age. The interaction gets tricky for anyone on medications shifting calcium flow, like diuretics or some osteoporosis drugs. Flooding the system with more calcium than expected can push levels out of range, triggering cramps or even more serious symptoms if the kidneys can't keep up. Doctors at Mayo Clinic have highlighted these risks, explaining that changes can slip past until symptoms shout for attention.

Advice for Avoiding Problems

Doctors and pharmacists keep up with complicated charts of drug interactions. The best move is a conversation before stacking lysine on top of other pills. While many folks don’t want another appointment, pharmacists back home—who know your list—can give real-world advice. Bringing supplements to each medication check-in also makes a difference. Skipping this step risks letting small problems snowball.

Even with over-the-counter creations, simple isn’t always safe. The Food and Drug Administration doesn’t treat supplements with the same eye as prescription medicine. Quality, purity, and ingredients vary by brand, making honest discussions with trusted medical professionals more important than any label. Keeping track and listening to what the body tells us offers more protection than hoping for the best.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2S)-2,6-diaminohexanoic acid hydrochloride |

| Other names |

L-Lysine HCl L-Lysine Monohydrochloride L-2,6-Diaminohexanoic acid hydrochloride Lysine hydrochloride |

| Pronunciation | /ˌelˈlaɪsiːn ˌhaɪdrəˈklɔːraɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,6-diaminohexanoic acid hydrochloride |

| Other names |

L-2,6-Diaminohexanoic acid hydrochloride L-Lysine HCl Lysine monohydrochloride L-Lysine HCl salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛlˈlaɪsiːn ˌhaɪdrəˈklɔːraɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 657-27-2 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `"data:chemical/x-jmol;base64,MC4wMA=="` |

| Beilstein Reference | 1209275 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:86627 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201481 |

| ChemSpider | 15521 |

| DrugBank | DB00114 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03e1434925 |

| EC Number | 200-713-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 14996 |

| KEGG | C00047 |

| MeSH | D008235 |

| PubChem CID | 62698 |

| RTECS number | OH0700000 |

| UNII | 6F4NNY28UA |

| UN number | UN3339 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID6037278 |

| CAS Number | 657-27-2 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3571506 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:61347 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201477 |

| ChemSpider | 78616 |

| DrugBank | DB14540 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b2d6c5-2da0-48c7-8ea6-afa825de3b10 |

| EC Number | 3.5.3.6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 84897 |

| KEGG | C00250 |

| MeSH | D008232 |

| PubChem CID | 6137 |

| RTECS number | OJ6365000 |

| UNII | 6Y9UM37VKK |

| UN number | UN3339 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5072323 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H15ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 182.65 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.98 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble in water |

| log P | -3.0 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.79 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.79 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -13.2e-6 cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 4.21 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H15ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 182.65 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.28 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble in water |

| log P | -3.0 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.79 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 9.06 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.6×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.570 |

| Dipole moment | 3.03 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 154.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -531.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | –3484 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 192.4 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -587.8 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3347 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA21 |

| ATC code | A16AA21 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS02 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. |

| Precautionary statements | Store in a well-ventilated place. Keep container tightly closed. Wash thoroughly after handling. Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. Avoid breathing dust. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 474°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (Oral, Rat): 4,680 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat LD50 > 10,000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | Not listed |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 70 mg/kg |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. |

| Precautionary statements | Wash hands thoroughly after handling. Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. If swallowed: Call a poison center/doctor if you feel unwell. Rinse mouth. Dispose of contents/container in accordance with local regulations. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 370°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | Oral Rat LD50: 5,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 4.3 g/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | Not listed |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 98.5% |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

L-Lysine D-Lysine L-Lysine sulfate L-Ornithine L-Arginine L-Lysine acetate |

| Related compounds |

L-Lysine DL-Lysine L-Lysine sulfate L-Lysine acetate L-Ornithine L-Arginine |