L-Leucine: A Closer Look at a Crucial Amino Acid

Historical Development

Back in 1819, the German pharmacist Henri Braconnot discovered leucine in the process of boiling muscle and wool with strong acids. Scientists spent years trying to understand this isolated white substance, eventually linking it to protein metabolism by the early 20th century. For most of the 1900s, research on leucine rolled quietly in the background until the rise of body-building and sports science in the late 1970s brought branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) into gyms and laboratories. Today, fermentation technology produces food-grade leucine at scale, giving athletes, patients, and food manufacturers widespread access to a compound once limited to academic curiosity or rare dietary sources.

Product Overview

L-Leucine belongs to the trio of branched-chain amino acids, sharing the spotlight with isoleucine and valine. It shows up in powders, tablets, capsules, and injectables—each form serving a different segment, from fitness fanatics scooping it into shakes, to clinicians preparing parenteral nutrition. On labels, purity holds attention: pharmaceutical users demand >99% L-isomer, while supplement brands trade on certifications like GMP or USP grade. Bulk suppliers ship leucine in drums lined with food-contact plastics, always handling the product to limit moisture exposure, which keeps purity steady from warehouse to end user.

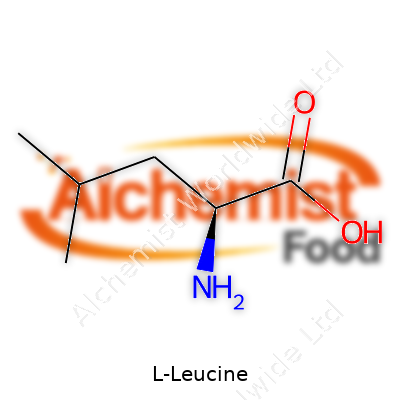

Physical & Chemical Properties

Crystalline L-Leucine appears as an off-white to white powder with a subtle, bitter taste and faint odor. The molecule (C6H13NO2) resists dissolution in cold water but disperses better in hot water and dilute acids. Boiling point hits 293°C with decomposition, no usable melting point shows up below that. L-Leucine's isoelectric point sits around pH 6.0. In the lab, it stands out due to its optically active (L-) form, splitting easily from the D-isomer by chiral chromatography or fermentation. True to its branched structure, L-Leucine contributes hydrophobic character to proteins, playing into taste science and protein engineering.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Regulations force producers to be precise: assay results hit labels with accuracy, typically not dipping below 98.5%. Moisture content must fall under 1%, heavy metals stay below 10 ppm, and microbiological tests exclude E. coli and Salmonella contaminants. Nutritional claims zero in on serving size by weight, commonly 2-5 grams per portion in nutrition products. The label will often warn consumers with allergies due to the risk of traces from corn, beets, or other plant fermentations. Products complying with European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) or U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) standards include batch codes, manufacturing dates, and proof of GMP compliance, giving consumers a trail of trust straight back to production.

Preparation Method

The bulk of modern L-Leucine comes from microbial fermentation. Producers feed carbohydrate-rich substrates (corn syrup, glucose, beet molasses) to strains of Corynebacterium glutamicum or Escherichia coli, which, after several days’ growth in stainless steel fermenters, excrete leucine into the broth. Protein precipitation, filtration, purification, and crystallization steps follow, tailored to squeeze out high-purity, food-grade leucine while removing other amino acids and fermentation residues. Chemical synthesis, while technically possible, rarely makes sense anymore due to high cost, environmental, and chiral purity headaches. Food-derived sources, like whey protein hydrolysate, supply only traces.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemists can modify L-Leucine to serve specialized needs. Esterification creates leucine esters that cross cell membranes faster, relevant for injectable drugs. Acetylation and N-carbamoylation protect the amine group, aiding peptide synthesis and sequencing. In industry, researchers use radiolabeled leucine to trace protein turnover in living organisms, a classic metabolic experiment. Under acidic or high-temperature processing, L-Leucine’s side chain can degrade to isovaleraldehyde—cue caution in high-heat food technology. The amino group readily forms peptide bonds, while transamination (yielding α-ketoisocaproate) plays a big role in the body’s nitrogen balance. Each modification offers a new angle for food science, pharmaceuticals, or lab research.

Synonyms & Product Names

L-Leucine answers to a handful of synonyms, from 2-amino-4-methylpentanoic acid to its common abbreviation, Leu. In supplement aisles, look for BCAA powder or branched-chain amino acid capsules—L-Leucine usually leads the ingredients as the key driver. Pharmaceutical orders use United States Adopted Name (USAN) 'Leucinum' or European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) references. Japanese manufacturers may use 'BCAA L-LEU' or specific lot numbers for traceability. On global import/export registers, HS codes connect L-Leucine to commodity databases for tariff and safety screening.

Safety & Operational Standards

Quality control sets the tone in plants handling L-Leucine. Workers don gowns, gloves, and masks to limit microbial risks and product loss, while equipment undergoes steady cleaning validation. Companies run risk assessments against cross-contamination, allergenic carryover, and dust explosion hazards, as the fine powder stirs easily into the air. Allergen statements track production sources, especially where fermentation switches between genetically modified and non-modified strains. For transportation, the classification falls under non-hazardous materials, provided purity guidelines and temperature controls hold steady. Audits verify adherence to HACCP, ISO 22000, and cGMP protocols. The finished product needs its batch testing paperwork and (for export) attestation certificates, keeping regulators satisfied and customers reassured.

Application Area

Dietary supplements build their protein content and muscle-repair reputations on L-Leucine, often marketing “anabolic” blends to athletes chasing recovery or muscle growth. Hospital formulas and oral rehydration solutions, especially for liver disorders or metabolic syndromes, call for precise L-Leucine dosing to manage catabolic states. In animal nutrition, feed integrators spike swine and poultry diets to optimize growth, using fermentation-derived leucine to replace expensive fishmeal or soy. Food industry developers engineer texture and taste or boost protein scores in plant-based products with isolated BCAAs, aiming to match the functional benefits of traditional meat or dairy. Biomedical labs leverage radiolabeled leucine as a reliable marker for tracking protein synthesis, turning out Nobel-winning research into protein metabolism. Powdered drinks, energy bars, intravenous solutions, and baby formula—every aisle stocks a role for L-Leucine.

Research & Development

Ongoing research links L-Leucine closely to mTOR pathway activation, fueling studies on aging, diabetes, and muscle wasting. Investigators unpack how subtle changes in leucine signaling spark muscle synthesis in young adults but might tip into metabolic stress in older adults or those with kidney trouble. Biomedical engineers study sustained-release formulations and bioavailability boosters that help the body use fractional doses more efficiently. The field watches gene-edited microbial strains and green fermentation technologies, which promise higher yields, less waste, and lower costs. Analytical chemists sharpen detection tools to ensure purity, tracing D-isomer levels or contaminants down to the ppm or ppb range. Each breakthrough brings new claims for functional nutrition and medical treatments, fueling debates over safety limits and optimal intake.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists track L-Leucine’s safety at dietary and therapeutic doses by screening for kidney, liver, and neurological effects. Studies in healthy adults point to a broad safety margin, with excess oral intake (up to 500 mg/kg/day) showing no adverse changes in serum chemistry or organ weight in most trials. Long-term megadose studies flag risks for those with genetic disorders like maple syrup urine disease or chronic liver disease, where abnormal amino acid buildup will harm the body. Animal studies probe possible neurotoxicity, especially at levels 50 to 100 times ordinary consumption, but toxicity relies mostly on a pre-existing metabolic vulnerability. Regulatory agencies remind manufacturers to avoid selling ultra-concentrated supplements without clear warnings, since toxic effects stack up from cumulative or unmonitored self-use.

Future Prospects

The push for plant-based nutrition, medical food innovation, and personalized wellness keeps L-Leucine in demand. Functional beverages, meal-replacement bars, and clinical nutrition shakes look set to bump up their content as sports diets and disease-prevention claims crowd package labels. Gene-edited microbes and circular bioeconomy methods cut the environmental impact of amino acid synthesis, offering a cleaner future for ingredient sourcing. Detailed metabolomics and precision nutrition, powered by advances in wearable biosensors and personalized tracking, will likely shift how we see L-Leucine intake—more as a tuned variable in health, less a one-size-fits-all standard. Regulatory frameworks will evolve with these trends, translating the latest toxicology and efficacy studies into tighter labeling, clearer guidance, and safer dosing for everyone from infants to the elderly.

What is L-Leucine used for?

What Makes L-Leucine Stand Out?

L-Leucine often grabs attention in sports nutrition circles. Walk into a gym and ask about muscle recovery or protein synthesis, and someone will mention this amino acid. What’s the big deal? It belongs to the group called branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), along with isoleucine and valine. Out of these, L-Leucine plays a unique role. It sparks the process that helps build new muscle tissue in the body, turning the switch for muscle protein synthesis. Without enough of it, those hours at the squat rack go to waste more easily.

Muscle Maintenance and Recovery

After heavy workouts, muscles need time and raw materials to rebuild. L-Leucine provides one of those essentials. It helps muscles recover, especially after tough exercise sessions or long endurance efforts. Studies have shown that supplementing with L-Leucine can support muscle growth and stop muscle breakdown in older adults and athletes alike. In my own training, adding a scoop of BCAA with plenty of leucine seemed to limit next-day soreness and kept my progress more steady.

Why Protein Quality Matters

Eating enough high-quality protein matters not just for athletes, but also for those just trying to stay strong into old age. Foods packed with L-Leucine—think eggs, beef, chicken, fish, cottage cheese—tend to show better results for muscle repair than sources with less of it. Research points out that you need about 2-3 grams of leucine in a meal to get the best muscle-building response. Rely on grains or veggies alone, and you’re not likely to hit those targets. That’s a real concern for vegetarians or vegans. Plant-based eaters often turn to supplements to fill the gap.

Beyond Muscle: Other Potential Benefits

L-Leucine interests more than just athletes. People with chronic illnesses or facing surgery sometimes lose muscle quickly. In hospitals, doctors often look for ways to slow down that loss, especially in older adults. Some clinical studies suggest adding L-Leucine to diets in these situations can help keep patients stronger and more mobile. While researchers haven’t answered every question about how much is best, the evidence points in the right direction.

Possible Risks and Smart Use

Like most supplements, L-Leucine works best as part of a bigger plan—one that includes regular activity and a good diet. Taking too much without enough of the other essential amino acids doesn’t make sense. Some people chase higher and higher doses, but more isn’t always better. Too much can burden kidneys over time, or throw off the balance with the body’s other amino acids. Sticking to amounts used in research—usually around 2-5 grams per serving with meals—offers more safety and fewer risks.

Looking at Solutions

Better nutrition education would help people, especially older adults and vegetarians, get more from their diets. Doctors and trainers need clearer guidelines for using amino acid supplements in both health and disease. In a world where people spend billions every year on muscle-building products, more independent research can help cut through hype. For me, focusing on high-quality food and using science-backed supplements only when there’s a real need leads to lasting results, not just quick fixes.

What are the benefits of taking L-Leucine supplements?

What L-Leucine Actually Does for the Body

L-Leucine gets a lot of attention in the fitness world, but its value goes deeper than flashy marketing. As one of the three branched-chain amino acids, it plays a central role in muscle building. Anyone who's spent time lifting weights learns quickly that proteins drive change, but not all amino acids work the same way. Out of all of them, L-Leucine stands out for its power to flip the switch on muscle protein synthesis. I’ve seen people hit plateaus in their training and break through by simply increasing high-leucine foods or adding a supplement.

Muscle loss creeps in with age or during intense training. Research consistently points to L-Leucine as a key player in stopping that breakdown. The journal Frontiers in Physiology reports that Leucine not only sparks muscle growth, it fights the kind of muscle wasting that happens in elderly adults. I’ve watched older relatives struggle with muscle weakness, and shifting their diet to include leucine-rich foods made a real difference in their daily strength.

L-Leucine, Recovery, and Athletic Performance

The sore muscles that follow a tough workout tell you something's happening, but recovery matters as much as the exercise. Leucine helps speed up recovery by reducing muscle damage. Endurance athletes, powerlifters, and casual gym-goers—anyone who pushes hard—wants to bounce back quickly. The International Society of Sports Nutrition highlights how taking L-Leucine before or after exercise can cut recovery time, letting folks train more often and with higher intensity.

I've trained for half-marathons and had stretches where progress stalled. Increasing protein alone didn’t move the needle, but focusing on leucine intake finally made things click. Recovery improved, and so did performance. That firsthand shift aligned with studies I’d followed, and it’s a pattern seen often in gyms and athletic training centers.

L-Leucine and Weight Management

People associate amino acids with muscle, but ignoring their impact on weight management misses the mark. Leucine acts as a signaling molecule for fat metabolism. It encourages the body to keep muscle during calorie deficits—a huge benefit for anyone dieting. In my own experience dropping weight after bulking season, prioritizing foods rich in leucine meant hanging onto muscle while trimming fat. BYU researchers published work showing that supplementing with Leucine during calorie restriction helps spare lean muscle and support metabolic rate.

Safety and Smarter Supplement Choices

Safety comes up often in discussions about supplements. Leucine occurs naturally in many foods—beef, eggs, dairy, and some beans. Most people get enough through meals, but strict vegetarians or older adults might fall short, making supplements a solid option. Doses in clinical trials range from 2 to 4 grams per day. Going far above that can cause imbalances, so it’s smart to stick close to recommended amounts. Consulting with a healthcare professional always makes sense, especially for anyone with kidney issues, since excess protein can put stress on kidneys in some cases.

Better Nutrition for Real Results

Focusing on L-Leucine isn’t just about chasing bigger muscles; it’s about building a resilient body, encouraging recovery, and holding onto hard-earned progress. Those goals matter to more than just bodybuilders. Anyone bouncing back from injury, looking to keep strength with age, or aiming to push their limits in training stands to gain from adding leucine to their nutrition plan—preferably through quality food sources, but supplements offer convenience when that’s not possible.

Are there any side effects of L-Leucine?

L-Leucine in the Spotlight

Head into any supplement store, and you’ll spot L-Leucine on shelves promising athletic muscle growth and faster recovery. Plenty of gym-goers already swig powders loaded with branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), and L-Leucine stands out as a muscle-building favorite. This amino acid helps signal muscle protein creation, which matters for anyone trying to keep or build muscle mass. Its popularity grows every year, with more people looking to squeeze extra results from their workouts.

The Big Question: Are There Side Effects?

No supplement comes without questions, especially as intake goes up. Most folks eating balanced diets get enough L-Leucine from foods like chicken, beef, tofu, or eggs. Extra L-Leucine comes into play through powders or capsules, especially among bodybuilders who think more will give larger muscles. If you stay within the recommended range—usually around 2-5 grams per day for adults—side effects rarely show up.

Push beyond moderate amounts, and things can shift. Too much L-Leucine in your system risks raising ammonia in the blood, giving you headaches, fatigue, or trouble concentrating. Extra intake may put a strain on kidneys, especially for anyone already dealing with kidney problems. Rarely, high doses link to low blood sugar or disruption of other amino acids in your body. The science here gets tricky, but those with an inherited disorder called maple syrup urine disease definitely need to skip L-Leucine, since their bodies can’t break it down properly.

Diving Into the Science and Real-world Evidence

Some nutrition researchers point out that studies on high-dose L-Leucine don’t fully cover long-term use, especially in healthy adults. Most clinical trials offer snapshots over several weeks, not years. Meanwhile, millions safely use L-Leucine daily, especially those fueling serious training with added BCAAs. Personal experience and anecdotes show that moderate L-Leucine supplements rarely lead to trouble in otherwise healthy adults. As someone who has cycled through BCAA powders during intense training blocks, I noticed more positive results in recovery than any unpleasant aftereffects—though I kept an eye on total protein and hydration.

Label warnings on supplements show the industry’s caution, not a guarantee of harm. That said, anyone noticing headaches, nausea, or odd mood changes tied to a new supplement should trust their instincts and listen to their body. Consulting a physician or registered dietitian, especially for those with pre-existing health issues, gives extra peace of mind.

Supporting Safe Use and Finding Balance

Diet always forms the base for health, and supplements serve best when filling unique gaps—not as a replacement for whole foods. Athletes or older adults looking to support muscle function might benefit from a little extra L-Leucine, though getting this amino acid through chicken breast, lentils, or dairy feels safest and comes with bonus nutrients. If aiming for higher doses of L-Leucine, especially long-term, checking in with a health professional and running routine bloodwork helps catch any issues early.

The best solution for most: Stick with food when you can, keep supplement doses low, and treat any sign your body gives you as worth noticing. Most folks chasing fitness goals want an edge, but wise choices protect those gains far better than a powder alone.

What is the recommended dosage for L-Leucine?

Why L-Leucine Matters to Active People

Walk through any gym or supplement store these days and someone will tell you about L-Leucine. This essential amino acid, known for jump-starting muscle protein synthesis, has become popular among folks looking to build muscle or recover faster after workouts. Since our bodies can’t create L-Leucine, we rely on food or supplements for our supply. Science backs its value for muscle growth, especially for people hitting the weights or working hard on their feet.

Recommended Dosage: What Studies and Experts Say

Most research and nutrition experts settle around 2 to 5 grams of supplemental L-Leucine daily to trigger muscle-building effects. That number reflects real world habits of athletes and gym-goers who add extra L-Leucine, on top of what comes from food. For the average adult, people usually get about 2 to 8 grams a day straight from food sources like beef, chicken, eggs, dairy, or soybeans. But folks with active training routines, older adults looking to preserve muscle, and anyone who eats little animal protein often aim higher.

Some sports nutrition guidelines point out that to really switch on muscle protein synthesis after exercise, a single serving of 2 to 3 grams of pure L-Leucine does the trick. That's because L-Leucine is the sparkplug of the process, more than the other branched-chain amino acids. It's rare for studies to suggest more than 5 grams per dose. And doses much higher may only end up as expensive urine, since the body can only use so much at once.

Potential Risks and Who Should Pause

Most people tolerate modest doses of L-Leucine without trouble. But like any supplement, more isn’t always better. Consistently taking over 10-12 grams daily—especially outside meals—can lead to side effects like stomach upset or headaches, according to clinical reports. People with kidney or liver concerns often avoid heavy protein and amino acid supplements without medical advice. Even healthy adults get the best results by keeping the focus on balanced diets first, with supplements only filling the gaps.

Ways to Get Enough L-Leucine Without Guesswork

Experts agree: food first, powder later. Eggs, lean meats, Greek yogurt, even lentils or nut butters all deliver real, digestible Leucine. If you train with intensity or push for more muscle, you can check your typical meals using free food trackers to estimate your baseline intake. If you fall short, then well-timed supplements make sense—ideally soon after training, and always as part of a meal with other quality protein sources.

Some whey protein powders serve up more than enough. Many have about 2-3 grams of L-Leucine per scoop without any need to buy it by itself. Athletes aiming for peak performance sometimes use targeted BCAA blends if their daily protein is low. Just make sure each serving lines up with what proven research says actually works—rather than megadosing and hoping for magic.

Smart Use, Better Results

L-Leucine builds strength, but only as one piece in the bigger puzzle of diet, training, and healthy routines. At the end of the day, hitting the sweet spot of 2 to 5 grams, timed smartly after workouts and tracked alongside total protein intake, delivers the benefits that research supports. Consulting a sports dietitian or a medical professional before big changes always adds an extra layer of safety, especially for those with health conditions or on multiple supplements. No supplement outperforms a solid overall nutrition plan.

Can L-Leucine help with muscle growth?

Understanding L-Leucine's Place in Muscle Building

Walk into any gym, and it won’t take long before someone mentions amino acids. L-Leucine stands out among the crowd. It’s one of the three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and plays a central role in building muscle, but people toss supplement tubs into their carts without always weighing what science says about its impact.

The Science Behind L-Leucine

L-Leucine gets plenty of attention for one main reason: it flips the switch in muscle protein synthesis. Our bodies depend on all nine essential amino acids to grow and repair muscle, yet research out of both European and American labs keeps pointing to leucine as the amino acid that starts the process. The body can’t make it, so you have to get enough from food or supplements.

Studies, like those published in the Journal of Nutrition, show that consuming enough L-Leucine with a meal boosts muscle protein synthesis better than the same meal without it. Even so, eating just L-Leucine in isolation doesn't guarantee bigger muscles. Protein quality and daily intake still matter most.

Experience at the Gym

Ask bodybuilders or committed lifters, and they’ll say L-Leucine is an ingredient worth the hype. I’ve watched dozens of athletes chase after more muscle using BCAA powders or whey shakes loaded with this amino acid. When tracking their diets, many didn’t even realize how much L-Leucine they already took in from eggs, chicken, or Greek yogurt.

After years of training, it became clear to me that nothing replaces solid nutrition. The most noticeable gains always followed a bump in total protein, not extra doses of a single amino acid. Books like “Nutrient Timing” by Dr. John Ivy go in-depth on why variety wins.

Food vs. Supplements

The easiest way to get L-Leucine comes from eating. Meat, dairy, legumes, and soy all bring plenty to the plate. Three ounces of chicken breast can pack over 2 grams of it; even a handful of peanuts carries a boost.

Some people reach for supplements—especially vegetarians or vegans who don’t eat much animal protein. Powders and capsules can help fill a gap, but they don’t make up for a diet lacking other essential nutrients.

The Safety Question

L-Leucine supplements generally look safe when taken in recommended amounts. The risk climbs for those who double or triple their servings, thinking more means better. Too much can stress the kidneys, especially in folks with pre-existing conditions.

Doctors and nutritionists often suggest sticking to real food, varying the diet, and only adding in powders when health goals demand it—such as injury recovery, or heavy training blocks.

Better Ways to Build Muscle

Getting stronger or more muscular asks for patience. Key pillars stay the same: challenge the body with resistance training, prioritize recovery, and eat enough protein every day. L-Leucine matters, but it works best as part of the whole package.

People searching for an edge might give L-Leucine a shot, but nobody should ignore sleep, consistency, or balanced meals. Based on research and what’s shown up consistently in training logs, that kind of foundation always pays the biggest dividends for muscle growth.

What is L-Leucine and what are its benefits?

What is L-Leucine?

L-Leucine belongs on the short-list of nutrients that keep your muscles working and recovering. It’s an amino acid—a building block that your body grabs from food or supplements since you can’t make it on your own. You find it in chicken, beef, eggs, lentils, soy, and plenty of plant proteins. Behind plenty of training plans, nutrition advice, and ‘clean eating’ recipes, you’ll find at least a little talk about amino acids like leucine, because athletes have known for years how much these nutrients push growth and recovery.

Why L-Leucine Stands Out

Not all amino acids carry the same punch, and L-Leucine holds a special reputation among gym-goers and those dealing with muscle loss. On a personal note, after training hard for a marathon or heading back to weights after a long break, adding leucine-rich foods or supplements always feels like an upgrade to recovery and soreness. Scientists back up this gut feeling: studies show that L-Leucine ‘switches on’ protein synthesis, so muscles rebuild bigger and stronger after a tough session.

There’s research from the Journal of Nutrition suggesting that getting enough L-Leucine leads to faster muscle repair and less breakdown, which becomes more important with age or during any illness or injury recovery. Athletes invest in L-Leucine-heavy shakes after workouts for a reason—they’re trying to speed up adaptation and stay ready for the next challenge.

L-Leucine’s Role in Everyday Life

You don’t need to be a bodybuilder to benefit from more L-Leucine. For aging adults, muscle wasting can quietly make daily tasks harder. Doctors sometimes recommend more protein, but what actually helps is targeting the amino acids that do the most work. L-Leucine fits here, helping prevent the slow muscle loss tied to aging or bed rest.

Research from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition suggests that 3-4 grams per meal helps trigger muscle protein synthesis. In real food, that’s roughly what you get from four large eggs, a chicken breast, or a large scoop of whey protein. Not everyone hits that target just by eating steak and eggs every day, and vegetarians sometimes see bigger gaps. So, L-Leucine supplements become a straightforward option for anyone struggling to hit those marks.

Concerns and Practical Advice

No nutrient works in a vacuum. L-Leucine works best with enough total protein, balanced meals, exercise, and a lifestyle that supports rest and recovery. Over-supplementation has risks too; some studies mention potential strain on kidneys, especially if there’s a history of kidney conditions in the family. The Food and Nutrition Board hasn’t set a tough daily upper limit, but doctors suggest moderation.

For anyone thinking about using L-Leucine as a supplement, a chat with a medical professional or dietitian adds peace of mind. They’ll help decide if it fits specific needs or medical situations.

Final Thoughts on L-Leucine’s Benefits

L-Leucine might sound technical, but its impact shows up in real-life gains—muscle recovery, strength maintenance, and smoother aging. It stands out for both athletes and non-athletes. Building meals around protein-rich options and using supplements smartly can help unlock its benefits without going to extremes.

How should I take L-Leucine supplements?

Why L-Leucine Matters

L-Leucine draws the eye of anyone paying attention to sports nutrition and muscle health. This branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) doesn’t just make up your protein powder label’s ingredient list—it plays a direct role in muscle repair, blood sugar regulation, and even wound healing. If you spend much time in the gym or work a physically demanding job, it’s natural to wonder if taking extra L-Leucine gives your muscles or energy a noticeable boost.

Dieticians and trainers discuss L-Leucine often because our bodies cannot create it, so we get it through food or supplements. Research published in The Journal of Nutrition reveals that L-Leucine contributes heavily to muscle protein synthesis, which stands at the heart of effective training recovery. That’s why weightlifters and older adults looking to prevent muscle loss seek it out.

How Much to Take

Sticking to the facts, your diet probably brings in around 2-4 grams of L-Leucine per day if you eat animal-based proteins like chicken, beef, or dairy. Plant-based diets can fall short, which explains why supplement companies target vegans and vegetarians especially. According to the International Society of Sports Nutrition, an extra 2-5 grams before or after training lands safely within the studied range for healthy adults.

Personal responsibility comes into play here. Don’t jump to high doses. Too much L-Leucine can stress the kidneys and liver, especially in anyone with pre-existing problems. Your doctor should weigh in if you have concerns or take medications that affect amino acid metabolism. Start on the lower end, and see how your body reacts. If you notice digestive upsets, cut back. Hydration also matters; support your body by drinking plenty of water when supplementing.

Timing and Practical Considerations

Protein shakes after workouts get most of the spotlight, but L-Leucine’s role shines brightest right around exercise. Studies suggest that muscles take up these amino acids faster and use them more efficiently during the recovery window right after lifting or hard training. You’ll often find fitness enthusiasts mixing 2-3 grams of pure L-Leucine powder into shakes or cold drinks immediately following a workout. If your schedule keeps you away from the gym, adding L-Leucine to meals that lack complete protein brings benefits too.

Taste can throw people off, as L-Leucine’s bitterness isn’t easy to mask. Mix it with fruit juice or a flavored BCAA drink to help. Stick with products that list “L-Leucine” specifically in the ingredients because not all BCAA blends guarantee you’re getting enough per serving. Check for third-party testing; some companies openly display certification by NSF or Informed-Sport, which shows a real commitment to quality and transparency—values shared by health professionals and smart consumers alike.

Keeping Things Safe

Supplements don’t make up for a weak diet or sloppy training routine. Think of L-Leucine as one small tool, not the whole toolbox. I’ve met plenty of people who saw more progress just from improving their protein at each meal than from adding a pill here and there. RL-Leucine can join the mix if you’re pushing your workouts, healing from surgery, or find it difficult to get quality protein elsewhere. Always pay attention to how your body responds and stay up to date by following credible sources like registered dietitians or peer-reviewed studies. Whole foods should still play the biggest part in nutrition.

Are there any side effects of using L-Leucine?

What is L-Leucine and Why Do People Use It?

L-Leucine turns up in conversations around muscle recovery, sports nutrition, and aging. You find this amino acid in dairy, eggs, fish, soy, and even beans. Athletes and older adults often try supplements, hoping for added muscle strength, better recovery, or help with feeling less run down during workouts. Some brands market L-Leucine as a way to fight muscle loss, but anyone grabbing it off the shelf needs a clear picture of risks as well as rewards.

Side Effects: What Research and Experience Show

You eat L-Leucine every day if you get enough protein, but concentrated doses come with questions. Clinical studies suggest that most healthy adults tolerate moderate supplementation without big problems. People sometimes notice headaches, fatigue, or mild tummy trouble if they jump right into a high dose without letting their body adjust. Athletes I’ve coached occasionally mention mild bloating or loss of appetite after taking amino acid blends that feature extra leucine.

The bigger issue crops up with overdoing it. High amounts—well over 500 mg per kilogram of body weight—can mess with something called the “mTOR” pathway, which signals cells to grow and divide. One well-respected study pointed out concerns about elevated blood ammonia and kidney workload when L-Leucine gets taken in huge volumes over long stretches. In my conversations with sports dietitians, I’ve heard the same thing: your kidneys don’t like surprises, especially from mega-doses of isolated amino acids.

For most, standard supplement doses won’t cause big spikes in risk. The trouble starts when people think, “If a little helps, a lot will work miracles.” Studies led by teams at big research hospitals have shown this thinking pushes stress onto organs that filter wastes. That might not matter for short-term use, but people with kidney disease, liver problems, or rare metabolism issues need to walk away from high-dose L-Leucine, not just cut back.

Who Should Pay Closer Attention?

Kids and teens, pregnant folks, and anyone with a personal or family kidney history should use more caution. Neurologists sometimes point out another risk: extremely high amounts can change the balance of branched-chain amino acids in the brain, and in rare cases, that can trigger mood changes, confusion, or jitteriness. None of these show up in every case, but they happen enough in the real world to make regular checks with a qualified healthcare provider a smart idea.

One Way Forward: Keep Use Simple and Watchful

If someone wants to try L-Leucine, checking current protein intake first makes sense. Food sources keep dose low and steady. Supplements might help edge up that intake, but keeping the dose low and following advice from dietitians cuts risk. For those with health conditions—especially kidney or liver challenges—L-Leucine isn’t the place to experiment alone. Good health means more than strong muscles. Too many pills or powders cause more trouble than the original problem, and the body rarely forgives long-term overload. For most people, a varied, protein-rich diet will offer all the leucine needed—no side effects attached.

Is L-Leucine safe for daily use?

What L-Leucine Does in the Body

L-Leucine plays a critical role in muscle repair and growth. After years of training and watching athletes push their bodies, the conversation about amino acids comes up over and over. L-Leucine stands out because it helps trigger muscle protein synthesis more than most. People look to it for support during strength training or when working through injuries. Foods like chicken, fish, and eggs supply this nutrient naturally, but supplement aisles offer powders and capsules for convenience.

Safety of L-Leucine: What the Evidence Shows

Studies over decades have tracked safety with different doses. Research conducted with adults taking up to 5-10 grams each day consistently shows few side effects in healthy people. Common sense also says moderation counts. Most nutrition organizations suggest between 2 and 5 grams as enough for active individuals. That level matches what folks get from regular meals, especially if they eat enough protein throughout the day.

When people go far beyond 10 grams daily, doctors notice issues like stomach discomfort or fatigue. High amounts, usually seen only with aggressive supplementation, can stress the kidneys or interfere with other amino acids. For anyone with kidney problems or certain rare metabolic disorders, high dose use isn’t a smart move. Most people won’t get anywhere near these levels unless taking several scoops a day.

Who May Benefit and Who Should Be Cautious

Athletes working through intense programs or older adults losing muscle with age could actually benefit from a steady supply of leucine. People with very low protein diets may fall short here. Experience in coaching has taught me muscle mass drops faster during long layoffs without enough of this amino acid.

For some groups, a little caution goes a long way. Pregnant women, children, and those with chronic kidney disease or maple syrup urine disease must talk with a doctor before even thinking about taking a leucine supplement. Health changes or new medications could also affect how well the body can process any amino acid, including this one.

Quality Counts: Supplement Safety Tips

Not every supplement delivers what it promises. Brands don’t always match the purity seen in research-grade products. A study from 2022 found several sports supplements sold online contained less leucine than the label advertised, or trace contaminants. If you want to use a powder or pill, looking for third-party certification (like NSF or Informed-Sport) keeps the risks down.

Combining supplements without paying attention to the rest of your nutrition leads to problems. Some athletes skip real meals thinking a scoop will do the trick. Food always brings a balance of nutrients and fiber that powders can’t replace. Supplement only fills in the gaps, not the whole plate.

Take-Home Thoughts and Possible Solutions

Most healthy adults sticking to food-based intake or moderate, targeted supplementation don’t face meaningful risks with L-Leucine. Sticking to products with solid quality checks, monitoring your intake, and balancing with other healthy habits matters most. Sports dietitians can help set a plan if someone’s unsure about what works for their body.

As research keeps evolving, it’s smart to keep an eye out for updates. Meanwhile, treating supplements as one tool rather than a shortcut keeps bodies stronger over the long haul.

Can L-Leucine help with muscle growth and recovery?

What L-Leucine Brings to the Table

L-Leucine stands out as one of the key amino acids people often talk about in the gym locker room. Folks trying to add muscle or recover from tough workouts pay close attention to what ends up on their plates, making L-Leucine a common topic. This amino acid lands in the “branch chain” group, alongside isoleucine and valine. Protein sources with plenty of Leucine include chicken, beef, tuna, and even plant choices like soybeans, peanuts, and lentils. High-protein meals tend to check this box for most active people.

Digging Into the Muscle Science

Muscles ask for amino acids to repair tissues worn down after exercise. Research from the Journal of Nutrition and Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise shows Leucine cues the muscle synthesis process in a way other aminos don’t quite match. Leucine takes the lead in activating mTOR, which acts as a signal for the body to kickstart muscle repair and growth. Studies with both younger and older adults keep pointing to Leucine as the piece of the puzzle that helps protein “do its job” and transform efforts in the gym into results seen in the mirror.

The Supplement Buzz—Hype or Help?

Lots of supplement products base their promises on these facts. The sports nutrition aisle offers powders, capsules, and drinks all touting Leucine or BCAAs for muscle support. Many folks swear by their post-workout shakes. Facing stacks of research and aggressive marketing, people sometimes wonder if scooping extra Leucine on top of an already balanced diet really delivers extra benefits.

Some human studies confirm slightly better muscle gains among athletes taking extra Leucine after workouts, as seen in trials out of Texas A&M and McMaster University. Extra Leucine leads to bigger increases in muscle protein synthesis, but these effects reach a ceiling beyond which more Leucine offers no further boost. If protein intake lags or comes from low-Leucine foods, a supplement patch might help bring things up to par. Otherwise, athletes eating enough high-quality protein often get all the Leucine they need from food alone, with no need for extra scoops.

The Recovery Angle

Beyond building bigger muscles, recovery matters, especially for those training more than three times per week. BCAAs help cut soreness and may drop post-exercise fatigue, but this field still leaves some questions open. Evidence leans toward Leucine supporting athletes in bouncing back faster, yet not all studies agree on the size of this advantage. For everyday fitness fans eating enough protein, the gains from Leucine may be smaller than the hype.

Simple Choices for Better Results

Most people chasing muscle goals can skip Leucine pills if their diet covers lean meats, eggs, dairy, or well-chosen plant sources. Keeping an eye on total protein makes a bigger difference than adding isolated amino acids. For vegetarians or older adults, a Leucine-focused supplement might be worth talking about with a nutritionist or doctor, especially if appetite or digestion makes it hard to reach protein targets with food alone.

Closing Thoughts

Muscle doesn’t grow from supplements alone. Training hard, resting enough, and picking food with plenty of protein lay the foundation. Science gives L-Leucine credit for its special role, but most strength athletes and fitness regulars find whole foods do the trick. Trends come and go on supplement shelves, yet beans, fish, and chicken have always been steady tools for muscle support and recovery.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2S)-2-amino-4-methylpentanoic acid |

| Other names |

L-2-Amino-4-methylpentanoic acid Leucine H-Leu-OH Leu |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɛl ˈluːsiːn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2S)-2-amino-4-methylpentanoic acid |

| Other names |

H-Leu-OH Leucinum 2-Amino-4-methylpentanoic acid Leucine |

| Pronunciation | /ˈliːjuːsiːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 61-90-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/data/chemdoodle/3D/L-Leucine.jmol` |

| Beilstein Reference | 0899536 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:25017 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL112 |

| ChemSpider | 564 |

| DrugBank | DB00148 |

| ECHA InfoCard | DTXSID1039236 |

| EC Number | 2.6.1.6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 7942 |

| KEGG | C00123 |

| MeSH | D007924 |

| PubChem CID | 6106 |

| RTECS number | OI6160000 |

| UNII | 6UH6D2VIKQ |

| UN number | UN1234 |

| CAS Number | 61-90-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1718784 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:25017 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL439875 |

| ChemSpider | 5536 |

| DrugBank | DB00148 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 13e6b5c7-488e-4e0e-9aa7-afe0b7616b47 |

| EC Number | 2.3.1.158 |

| Gmelin Reference | 5276 |

| KEGG | C00123 |

| MeSH | D007950 |

| PubChem CID | 6106 |

| RTECS number | OI0705000 |

| UNII | 6U83C4VZ8L |

| UN number | UN1237 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2020827 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 131.17 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.93 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | -1.19 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.36 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 2.36 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -13.2·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 5.9097 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 131.17 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.93 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble in water |

| log P | -1.1 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.33 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 4.36 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -8.43 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 4.9096 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 143.3 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -537.3 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | –2233 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 67.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -528.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3596.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A11AA06 |

| ATC code | A11AA06 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 Warning |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H335: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P261, P264, P270, P271, P272, P273, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P330, P337+P313, P362+P364, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 300°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat > 5000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral, rat: 12,000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | MV1180000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2,000 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| GHS labelling | GHS07 Warning |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H335: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P272, P280, P302+P352, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P312, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362+P364 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Flash point | > 185 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 300°C |

| Explosive limits | Explosive limits: "Dust may form explosive mixture with air |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 15,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral, rat: 12000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | NCL8888000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 1-3g per day |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Norleucine Norvaline Isoleucine Valine Leucic acid Alpha-ketoisocaproic acid |

| Related compounds |

Leucine Isoleucine Valine Norleucine Norvaline |