L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate: An Informal Deep Dive

Historical Development

L-Cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate carved out its spot in the world of science because folks wanted to get at the heart of protein structure and function. Back in the early 20th century, scientists worked to break down proteins and isolate building blocks. L-cysteine came out of all this cutting and sorting, and for years, people pulled it out of animal sources (like feathers and hair). Today, the move toward synthesizing cysteine reflects a broader change in chemical manufacturing—searching for more sustainable, reproducible, and often ethical methods. If you look at the shift from scraping it out of leftover biowaste to making it through fermentation, you notice attitudes about both safety and supply chain have changed along the way. Industry and academia now work together more than ever, pushing researchers to get creative about how to meet the demands of food, medicine, and biotech.

Product Overview

L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate looks like a white, crystalline powder. It’s got a faint sulfur odor you won’t miss if you spend any time in a lab. This compound gets used everywhere, from helping bread bakers whip up softer dough to enabling medical techs to stabilize injectable drugs. You’ll also run into it when companies manufacture cosmetic and personal care products. The product offers a reliable way to introduce cysteine into all these applications—think of it as a jack-of-all-trades that shows up wherever reducing or chelating abilities are needed.

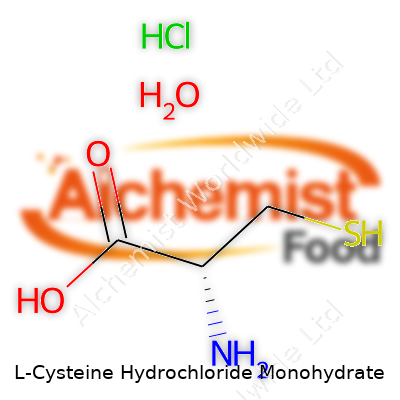

Physical & Chemical Properties

It’s water-soluble, slightly acidic, and melts near 175°C—give or take a degree based on how tightly the molecules stick together. The molecule itself, C3H7NO2S•HCl•H2O, includes both amino and carboxylic acid groups, so it gets along with all sorts of chemical neighbors. Not everyone appreciates the slightly sulfurous scent, but that functional group is what lets L-cysteine pull off strong antioxidant moves. The hydrochloride part gives it a sharp taste, which matters less in the factory than on bread or biscuits, but it definitely impacts usage in any end product.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Regulatory bodies—like the US FDA and EFSA in Europe—demand that L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate manufacturers keep labels clear: batch, purity level (often 98%+), and exact content of monohydrate. Tech specs also cover pH (about 1.5–2.0 in solution), solubility in water, residue after ignition, and heavy metals content. Food grade and pharma grade products have stricter tolerances for these numbers. Batch certifications and COAs generally back up product promises, with manufacturers opening their books for audits and keeping tight control over allergens and microbiological contaminants.

Preparation Method

Decades ago, companies made L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate by hydrolyzing feathers or even pig bristles. Today, biotechnologists often turn to fermentation—using non-pathogenic strains of E. coli or similar workhorse bacteria. These bugs crank out cysteine in big fermentation tanks using glucose or glycerol as feedstock, and people harvest the L-cysteine, purify it, and then react it with hydrochloric acid and water to yield the final monohydrate product. Each step takes careful control of temperature, pH, and nutrient composition to avoid batch-to-batch swings in quality. Purification typically involves activated carbon treatment, crystallization, and filtration, all the way to an odorless, pure powder that meets strict microbial and chemical safety standards.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

L-cysteine opens up a bunch of chemical doors thanks to its thiol group. That sulfur atom can participate in redox reactions, coupling with another cysteine to form cystine or reacting with other molecules to neutralize oxidants. In industrial settings, technicians use it to break down gluten networks in dough, making bread softer and fluffier. Chemists might modify cysteine by attaching protective groups to boost shelf life or alter solubility; it also acts as a key starting material for some antibiotics and vitamin preparations. Under the right conditions, cysteine can even serve as a ligand in coordination chemistry, partnering up with metals that play central roles in enzymatic or catalytic processes.

Synonyms & Product Names

You might spot L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate under names like “Cysteine HCl·H2O,” “Cysteine Monohydrochloride Monohydrate,” or on the label as E920 in some bread improvers. Drug and food catalogs sometimes shorten the moniker, calling it “L-Cys HCl” or just “Cys HCl Mono.” It helps to check the CAS number (52-89-1) to cut through the clutter and avoid confusion, especially because several forms exist, including anhydrous and S-carboxymethyl versions. Branding and supplier differences don’t change the underlying chemistry, but accuracy matters for anyone buying or selling across borders.

Safety & Operational Standards

Working safely with L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate means respecting its acidic and reducing properties. Contact with eyes and skin can irritate, so anyone in production gear sticks to gloves, goggles, and lab coats. Dust from the powder can bother the lungs, pushing facilities to install proper ventilation and dust capture. For food applications, strict protocols weed out cross-contamination, and pharma-grade batches meet sterility and microbial specs. Ethical sourcing matters too, tying back to ongoing debates about origins—most food manufacturers and regulators push for non-animal origin L-cysteine to address dietary, religious, and environmental concerns. Waste handling follows strict chemical disposal laws, and anyone that skips these steps risks tough fines or losing market access.

Application Area

L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate carries a bigger punch than folks realize. Bakeries and large food processors mix it into dough to control texture, aid yeast fermentation, and reduce mixing time. Medical formulations use it as a stabilizer in parenteral nutrition solutions and in medications that require a buffer against oxidation. Some biomanufacturing plants lean on L-cysteine to prep bacterial cultures or scale up cell-based processes—its nutritional value and impact on reducing oxidative stress pay off in higher yields. Even the cosmetics industry gets in on the act, putting L-cysteine derivatives into hair care lines that target damage repair and styling.

Research & Development

Today’s researchers push for greener, more scalable production—fermentation tops the list, thanks to rising attention on sustainability. Genetically modifying microbial strains to boost L-cysteine output while slashing by-products attracts heavy investment from both industry and government agencies. Analytical chemists continue refining rapid, high-sensitivity purity and contamination testing, since a stray metal ion or odor can shut down whole product lines. Teams work to unlock new uses—gene therapy and regenerative medicine being examples—by finding ways to safely pair cysteine’s chemistry with delicate biological structures. In the academic world, understanding how cysteine and its derivatives interact with human cell lines, particularly regarding redox balance and signaling, guides future pharmaceutical innovation.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists pay close attention to dietary and pharmaceutical levels of L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate. While cysteine is an amino acid found in the human body, excessive intake from supplements can challenge the balance in people with metabolic issues or certain inherited conditions. Oral consumption in typical food amounts appears safe, but chronic overdose raises the risk of kidney stones and can disrupt nitrogen metabolism. Animal studies have mapped acute and chronic exposure, showing a wide margin of safety for food use but underlining the need for upper intake guidelines. Modern toxicology labs analyze absorption, distribution, and metabolic breakdown to keep new medical and food applications within safe boundaries.

Future Prospects

Going forward, demand for L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate won’t slow down. Alternative sources, particularly fermentation using engineered microbes, look set to dominate manufacturing pipelines as they shave costs and improve safety profiles. Application areas will likely branch into precision medicine, especially as researchers learn more about its antioxidant and signaling functions in cell culture. Ongoing advances in analytical quality control will keep standards high, and technical tweaks in production methods may lower environmental impacts further. Increased international regulation and demand for transparent sourcing will keep suppliers on their toes, and the push for non-animal and environmentally friendly solutions seems unstoppable across food, pharmaceutical, and personal care industries.

What is L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate used for?

What You’re Actually Eating

L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate pops up in foods that fill grocery shelves every day. Bakeries rely on it in flour, as it helps dough stretch, knead, and shape. Croissants, bagels, sandwich bread: many of these fluffy, chewy textures don’t happen without amino acids like L-Cysteine. Flour treatment keeps production lines moving efficiently, so bread stays soft and bakes up the way people expect. The addition of L-Cysteine isn’t some distant factory secret; it’s a workaround to help bakers meet large-scale demand.

Benefits Beyond the Bakery

My own experience—spending weekends reading food labels—turned up L-Cysteine in more than just bread. It ends up in pizza crust, tortillas, and even some noodle brands. This amino acid breaks down tough gluten chains in flour, creating a finer grain and lighter bite. The science checks out: research published in the British Journal of Nutrition shows enzymes and amino acids like L-Cysteine shave hours off dough resting time, which makes fresh bread available faster.

Industrially, it saves time and resources. Reducing mix time and improving workability helps bakeries cut down on electricity, equipment wear, and food waste. For anyone struggling to cook for a family on a tight budget, these savings can mean lower bread prices at checkout. It’s a small chemical tweak, but one with a ripple effect across entire supply chains.

Supplements and Medicine

L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate plays a role in the supplement aisle, too. Human bodies break down food into amino acids, which rebuild muscles, skin, and hair. Some supplements supply extra L-Cysteine for people recovering from surgeries, chronic lung issues, or illnesses where the body burns through resources faster than it can replace them. Doctors know it helps form glutathione, an antioxidant the body uses to fight off oxidative stress. Hospitals administer L-Cysteine and its relatives to detoxify acetaminophen overdoses and clear mucus in some lung diseases.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers keep quality control tight on this compound because contaminants threaten patient safety. Years ago, concerns over animal-sourced L-Cysteine pushed the shift toward fermentation-based sources using plants or microbes. This means safer, allergy-friendly choices for more people, especially those following religious, ethical, or vegan diets.

Ethics and Transparency

Consumers deserve clear information about food sourcing. Surveys from groups like the Vegetarian Resource Group reflect ongoing confusion: even well-meaning companies do not always disclose how they produce L-Cysteine. My own research for family members with allergies meant endless phone calls to companies about their ingredient sourcing. As more manufacturers switch to plant-based fermentation, trust grows—but food transparency still has room to improve.

Looking Ahead

Finding L-Cysteine in so many foods and medicines made me rethink what’s really “natural” in modern diets. Instead of sidestepping this amino acid, smart manufacturing uses it to supply affordable, safe, and consistent products to families everywhere. Stronger labeling laws, greater transparency, and ongoing safety research will build trust and make sure people know what they put into their bodies. If food technologists keep listening to ethical concerns and scientific research, everyday consumers can count on clear answers—not just clever chemistry.

Is L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate safe for human consumption?

What’s Actually in Our Food?

Many people can’t find L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate on a store shelf, but you’ll see this name on plenty of food labels. This is an amino acid—the building block of protein—often made from natural sources like feathers or human hair. Food companies use it mostly to improve dough texture in bread, making that soft, fluffy sandwich bread so many folks love. Some people feel uneasy seeing scientific terms in their foods, so the question of safety keeps coming up.

Science Looks at Safety

L-cysteine has a long history in the world of food and medicine. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration calls it “Generally Recognized as Safe,” or GRAS, meaning experts consider it safe for its intended use. The European Food Safety Authority reviewed it and gave its approval too. These expert panels dig deep into toxicology studies, not just for short-term risks, but also the long haul.

I remember talking with a bread maker who explained how just a pinch of this ingredient helped big factories cut down on waste by making dough more predictable. He trusted the research behind it, knowing that regulators don’t just rubber-stamp chemicals. Real people challenge these approvals, and if companies want to keep selling bread, they don’t risk slipping something unsafe into the supply chain.

What About Allergies and Sourcing?

Concerns about L-cysteine mostly focus on where it comes from. While the compound itself is the same, folks with strict dietary rules or ethical beliefs sometimes worry about the source—feathers, hair, or plant materials. For those who want to avoid animal sources, some manufacturers offer plant-based options, but labeling isn’t always clear. If you’re vegan, kosher, or halal, checking with the producer stays important.

Food allergy issues rarely trace back to L-cysteine itself. Because it’s an amino acid naturally present in our bodies, the vast majority of people show no reaction at the levels used in food. Still, anything can cause trouble for someone with an extreme sensitivity, but there’s little evidence of widespread problems.

Dose Makes the Difference

Like with many substances, the amount added to food is key. Research shows the levels used in industry are far below the threshold where risk shows up. In medical treatments, much bigger doses get prescribed, especially for people with certain inherited disorders. Even then, doctors keep an eye out for possible side effects, but those doses far exceed what ends up in your average loaf of bread.

Reading Food Labels Still Matters

Over years of reading food labels for my own family, I’ve realized that science supports the safety of L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate for the general public. Even so, staying informed never hurts. Some shoppers feel better avoiding ingredients they can’t pronounce, choosing simpler breads or baking at home. That’s a choice worth respecting, especially with so many alternatives popping up in grocery stores.

Transparency Helps Build Trust

Food companies win consumer trust by sharing production details and sources. Demand for plant-based or synthetic amino acids keeps growing, and producers respond by labeling more clearly. Regulations encourage honesty, but shoppers asking questions drive real change faster.

For folks worried about risks, fewer processed foods and honest communication with brands offer practical solutions. Those who keep to plant-based diets can seek out companies that list their ingredients and sources openly.

People Want Safer, Simpler Choices

L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate has passed safety checks by global health authorities for decades. For nearly everyone, eating bread with this ingredient carries no additional health risk. Still, people have the right to decide what goes on their dinner table. Informed choices always put a little more power into the hands of shoppers, not factories.

What is the recommended dosage for L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate?

L-Cysteine’s Place in Health and Nutrition

L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate often pops up in lab reports, food labels, and nutrition guides. As an amino acid, it helps build proteins in the body. Your body can make it, but certain stresses or poor diets can drain reserves, which is why doctors look at supplementation for specific cases.

Digging Deeper: How Dosage Gets Determined

Dosage comes down to what someone needs, not a one-size-fits-all chart found online. Clinical research, input from nutritionists, and the dietary guidelines in the U.S. give us a starting point. The National Institutes of Health recognize that adults get most of their L-cysteine from diet, usually ranging from about 200 to 500 milligrams daily from food. Supplementation usually calls for measuring in the range of 50 to 600 mg per day for adults, depending on what a person lacks or requires according to their health profile.

Medical Use Cases and Real-Life Examples

L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate appears in clinical nutrition. Doctors use it to support people dealing with paracetamol poisoning or respiratory conditions, as this amino acid helps replenish glutathione, the antioxidant that keeps cells safe from damage. In these cases, prescribed amounts can range much higher—sometimes 600 mg up to several grams per day—under direct supervision. These are medical scenarios and don’t replace advice from a doctor. People with chronic illnesses, compromised livers, or who take certain medications require structured guidance, not over-the-counter fixes.

The Role of Food and Supplements

For otherwise healthy people, getting enough cysteine from foods like poultry, eggs, dairy, beans and oats usually covers daily needs. Taking supplements for general wellness typically doesn’t show extra benefit and, in cases of excess, might lead to unwanted effects like nausea or headaches. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration monitors supplement claims and sets limits on labels for safety reasons, but that doesn’t stop companies from making big promises. Using a supplement without talking to a healthcare provider leads to more risk than reward.

Risks from Ignoring Basics

Too much L-cysteine can bring its own problems. Doses over 2,000 mg per day regularly over weeks could trigger digestive problems or in rare cases, more serious concerns. People with asthma or sulfite sensitivity should tread carefully, as cysteine could prompt wheezing or allergic reactions. I’ve seen people double up on amino acid powders thinking it helps muscle building, only to land with an upset stomach or worse.

What Actually Matters Most

Listening to your body and qualified medical professionals beats following what’s trending on wellness blogs. Lab tests can show if your cysteine levels need help. Nobody benefits from chasing a “more is better” attitude with amino acids. Instead, focus on a well-rounded diet and consult a physician if considering supplements, especially at higher doses.

Moving Forward with Information, Not Hype

Guidance from certified dietitians and peer-reviewed research shape safe dosage ranges for nutrients like L-cysteine. Everyone’s health story plays out differently, and nobody should lean on supplements without real cause. Transparency, expert input, and evidence-based choices make for better long-term health than guesswork or imitation.

Are there any side effects associated with L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate?

What L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate Really Is

L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate shows up on food labels and in supplements, and folks sometimes wonder if it’s all that safe. It's an amino acid, meaning the body can use it for protein building and other important work. Manufacturers like its ability to keep dough stretchy and slow down spoilage in baked goods. Science journals point out that this ingredient comes from fermentation or sometimes even feathers. Most bodies recognize it since they naturally use similar amino acids every day.

What Do People Experience with L-Cysteine?

Plenty of people have never noticed a thing after eating foods containing L-cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration marked it as “Generally Recognized As Safe,” which means a history of broad use has shown little cause for alarm. That doesn't mean every single person has the same experience though.

Folks with allergies tend to be sensitive to a lot of things, so it’s not wild to worry about amino acids sourced from feathers or hair. Studies from the European Food Safety Authority haven’t found evidence of dangerous effects at levels found in bread and snacks, though rare allergic reactions pop up in case reports. Someone with a known allergy to specific animal proteins might see symptoms ranging from mild itching to breathing trouble, but those seem to be exceptions rather than the norm.

Possible Side Effects

Taking high doses in supplement form sounds appealing to some, especially athletes or those reading about detox routines. High amounts can sometimes hit the body the wrong way. Mayo Clinic data and case studies highlight stomach upset, nausea, or diarrhea in some cases where people overdo it. Like most things, moderation matters. The liver and kidneys already filter out excess amino acids, but flooding them can stress those organs, especially in people dealing with existing health problems. In extremely rare cases, long-term overuse could make asthma symptoms worse or throw off the body’s natural balance of minerals.

Who Should Watch Their Intake?

Most healthy adults don’t notice side effects when eating normal amounts from food. People who have a history of kidney or liver disease, or who take a lot of supplements, should talk with their doctor before loading up on extra L-cysteine. If someone takes drugs that influence cysteine breakdown—acetaminophen, for example—sticking to the standard daily dose matters. Pregnant and breastfeeding women should approach new supplements carefully, especially since safety studies in these groups stay pretty thin.

What Could Help Fix These Concerns?

Clear labeling helps, especially for those concerned about origins or allergies. Some folks feel strongly about animal-derived ingredients, so a bigger push for plant-based fermentation sources can keep more people at ease. Doctors and nutritionists should also check for supplement use during patient visits—people don’t always think to mention it, and some doctors forget to ask. Solid public information campaigns can spell out proper dosing, potential risks, and how certain groups face a higher risk. More research, especially focused on long-term and high-dose use, would help set stronger guidelines.

Advice from Real Life

I’ve had people ask about L-cysteine after seeing it on their sprouted bread or hair supplement labels. Most questions boil down to “Is this safe for me?” For the average shopper, this amino acid passes through without fuss. Still, those with unique health needs or heavy reliance on supplements should treat it like any supplement: respect the label, stay skeptical of mega-doses, and check in with a health care provider before making it a daily habit.

Is L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate derived from animal or plant sources?

Breaking Down the Source Debate

L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate keeps showing up on ingredient lists, from dough conditioners in bread to flavors in snacks. Most folks don’t think twice about it, but the source of this amino acid actually raises a lot of important questions. I’ve had my fair share of debates with health-conscious friends, some vegan, some not, who always ask: Is this building block coming from animals, or is it plant-based?

Historically, a large chunk of the world’s L-cysteine came from duck feathers, pig bristles, or even human hair. That picture sounds unappetizing and, honestly, makes label readers cringe. Food science aimed for efficiency, not ethics or dietary restrictions, so animal byproducts offered an easy supply. If it worked in the dough, not many companies paused to think about vegetarians or people with religious dietary rules. My own early days of trying to navigate vegetarian options felt like detective work. Food packaging rarely made the origins clear, and customer service lines often handed out corporate shrugs instead of solid answers.

Fermentation: A Turning Point in Production

In the last decade, demand for vegan and kosher-friendly foods exploded. Globalization pushed food companies into more markets. It was no longer enough to source ingredients the cheapest way. Now, food makers needed to tell people exactly how things got made. This push led to a big shift: microbial fermentation. By using friendly bacteria to ferment vegetable sources, producers managed to sidestep animal hair and bristles altogether. This method delivers high yields, keeps things consistent, and sidesteps the nastier PR of old-school sourcing.

China became a major power player in the amino acid market, so most of the world’s L-cysteine comes from factories there. Chinese manufacturers lead in both traditional and fermentation methods. Major Western food brands started leaning heavily on fermentation-based cysteine, especially after some outcry in the early 2010s. These days, it’s not unusual to find packaging or company websites specifically highlighting fermentation-derived ingredients. It responds to consumer demand for transparency—something I’ve seen many people ask for every time a news story breaks about food ingredients coming from animals without clear disclosure.

Why Source Matters to Consumers

This isn’t just “ingredient nerd” territory anymore. Jewish and Muslim consumers need certainty to keep products halal or kosher. Vegetarians and vegans want to make sure they’re not inadvertently supporting animal agriculture. Some people care less, but for a growing chunk of the population, details about origin are a dealbreaker. Allergies and sensitivities enter the mix, too—animal byproducts sometimes carry trace allergens or create risks for specific groups.

Some companies take the extra step of displaying certifications for their amino acids. I’ve found that third-party verification really helps cut through vague marketing speak. Kosher, halal, plant-based logos—these offer peace of mind. If a brand stays mum about its cysteine sourcing, customer service is the next stop. Sometimes, transparency needs a little nudge from a persistent caller or an informed buyer checking labels.

Pushing Toward Greater Transparency

With people asking tougher questions and new regulations catching up, it’s time for clear answers. Ingredient lists should actually reflect what’s inside. Brands embracing microbial fermentation for their amino acids can earn genuine trust by labeling it. This change won’t just benefit special diets—it lets everyone make informed decisions. It’s a small step in sourcing, but a big leap for food honesty.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-amino-3-sulfanylpropanoic acid hydrochloride monohydrate |

| Other names |

H-Cys-OH·HCl·H2O L-Cysteine HCl Monohydrate Cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate L-2-Amino-3-mercaptopropanoic acid hydrochloride monohydrate L-β-Mercaptoalanine hydrochloride monohydrate L-Cysteine hydrochloride hydrate |

| Pronunciation | /ˌelˈsɪs.tiːn haɪˈdrɒk.lə.raɪd ˌmɒn.oʊˈhaɪ.dreɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-amino-3-sulfanylpropanoic acid;hydrochloride;monohydrate |

| Other names |

L-Cysteine HCl Monohydrate L-Cysteine Hydrochloride H2O Cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate S-Cysteine hydrochloride monohydrate (R)-2-Amino-3-mercaptopropanoic acid hydrochloride monohydrate |

| Pronunciation | /ɛl ˈsɪstiːn haɪdrəˈklɔːraɪd ˌmɒnəˈhaɪdreɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7048-04-6 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3D model (JSmol)` string for **L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate** (commonly found in chemical databases): ``` NC(CS)C(=O)O.Cl.H2O ``` This is the **SMILES** string that can be used in JSmol or similar tools for visualizing the 3D structure. |

| Beilstein Reference | 3569731 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:61341 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201479 |

| ChemSpider | 21634495 |

| DrugBank | DB11360 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b231267a-4778-4ea9-8adb-8ea243bbdfe1 |

| EC Number | EC 200-157-7 |

| Gmelin Reference | 82774 |

| KEGG | C00097 |

| MeSH | D-Cysteine |

| PubChem CID | 61361 |

| RTECS number | MD0960000 |

| UNII | WFW6SBF5HM |

| UN number | Not regulated |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID6048568 |

| CAS Number | 7048-04-6 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3D model (JSmol)` string for **L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate**: ``` CN[C@@H](CS)C(=O)O.Cl.H2O ``` |

| Beilstein Reference | 3579535 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:61341 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201504 |

| ChemSpider | 22227 |

| DrugBank | DB00141 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.890 |

| EC Number | 3.1.1.10 |

| Gmelin Reference | 77537 |

| KEGG | C00097 |

| MeSH | D-Cysteine |

| PubChem CID | 61373 |

| RTECS number | MD0350000 |

| UNII | 7Y76O5S2T7 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2S·HCl·H2O |

| Molar mass | 175.63 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Slight odor of hydrochloric acid |

| Density | 1.3 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble in water |

| log P | -3.2 |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 1.71, pKa2 = 8.33, pKa3 = 10.78 |

| Basicity (pKb) | -8.3 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.6 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 0.828 D |

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2S·HCl·H2O |

| Molar mass | 175.63 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Faint odor of hydrochloric acid |

| Density | 1.3 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble in water |

| log P | -3.4 |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 1.71 (carboxyl), 8.33 (amino), 10.78 (thiol) |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 7.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | −8.2 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 5.2111 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 172 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -987.9 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1625 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 221.0 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -974.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1444 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA17 |

| ATC code | B05XA06 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Irritating to eyes, respiratory system and skin. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | Oral rat LD50: 1650 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 1890 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | RN 7049 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg body weight |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS05, GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315: Causes skin irritation. H319: Causes serious eye irritation. H335: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P271, P301+P312, P304+P340, P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | NFPA 704: 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | > 210°C (410°F) |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral - rat - 1,650 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 1890 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | MI7700000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg body weight |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Cysteine L-Cysteine Cystine N-Acetylcysteine L-Cysteine Hydrochloride DL-Cysteine Hydrochloride L-Cystine Homocysteine Methionine |

| Related compounds |

Cysteine L-Cysteine Cystine N-Acetyl-L-cysteine DL-Cysteine L-Cysteine hydrochloride L-Cysteine methyl ester L-Cystine dihydrochloride |