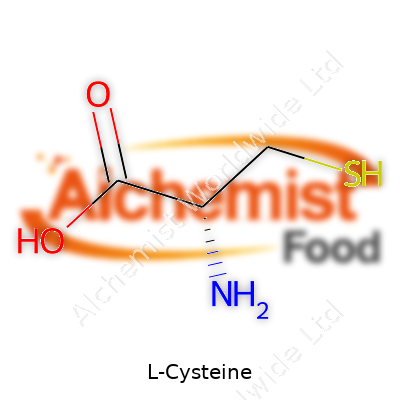

L-Cysteine: From Historical Roots to Future Frontiers

Historical Development

People discovered L-Cysteine in the 19th century, finding its prominent role as a building block of proteins. The early days saw extraction from animal sources, mainly duck feathers or hog hair, tapping into the byproducts of other industries. Chemists soon realized the influence of this amino acid in both health and technology. Over time, fascination with this molecule deepened. Demand for large-scale, consistent production sparked interest in new ways of making it, setting foundations for what we see across food, pharma, and biotech today. Historical records show that by the late 20th century, L-Cysteine found solid ground in food and drug regulations globally, reflecting both its usefulness and the complexities tied to sourcing and safety.

Product Overview

L-Cysteine belongs on lists of essential ingredients for many sectors. Whether in bread, where it softens dough, or in medical formulations—think mucolytic agents—it shows up time and time again. Food technologists value its reducing power for flour treatment, while pharmaceutical experts use it for specific therapies. Nutritional supplement lines praise its antioxidant capabilities, reminding us of its protection against oxidative stress. The raw compound often appears as a white crystalline powder, signaling purity and consistency to manufacturers measuring quality by sight as well as by test results.

Physical & Chemical Properties

L-Cysteine carries a distinctive sulfurous scent, which comes from the thiol group sticking off its side chain. The pure compound absorbs water from the air and dissolves easily in water but less so in alcohol. As an amino acid, it packs both carboxylic acid and amine groups, letting it slot into peptide chains or support various chemical reactions. A melting point of around 240°C stands out, setting boundaries for process engineers on how to handle and store the raw material. The strong reactivity of the thiol group sometimes proves tricky but creates many opportunities for creative chemistry.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Suppliers typically standardize L-Cysteine to meet food, pharmaceutical, or cosmetic grades. Product labels carry precise assay percentages—usually above 98% purity for direct human consumption. They include CAS number 52-90-4, chemical formulas, and warnings about storage away from moisture or high heat. Each certificate of analysis outlines heavy metal limits, microbiological standards, and allowable impurities, updating clients on compliance with regional and international food safety laws. Allergens, animal origin, and kosher or halal status also get specific mention as global markets expect transparency from ingredient suppliers.

Preparation Method

Manufacturers always look for better ways to make L-Cysteine. Early methods stuck to hydrolyzing animal-based keratin, but public pressure and cost forced change. Today, fermentation carries the bulk of worldwide production. Genetically engineered strains of E. coli churn out the amino acid efficiently from glucose, scaling up the process and reducing dependency on animal waste. This shift dramatically dropped costs, improved purity, and addressed ethical concerns, feeding into demands for vegetarian or vegan sourcing. Some labs still rely on hydrolysis for specialty needs, but the future clearly favors biotech approaches for cleaner and more predictable supplies.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The chemical power of L-Cysteine comes from the reactive thiol (sulfhydryl) group. This –SH group snaps into disulfide bonds, both breaking and making links inside proteins or small molecules. In bread dough, cysteine reduces gluten networks, softening texture and shorting knead times. In lab settings, scientists exploit this reactivity to label proteins, synthesize derivatives, or build larger peptides. You often spot derivatives like N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), where an acetyl group covers the amine end, turning it into a popular drug for treating acetaminophen poisoning and chronic lung issues. Researchers have explored selenocysteine, methylated versions, and other analogs to expand its application set.

Synonyms & Product Names

L-Cysteine travels the world under several names. Chemists read the labels L-2-amino-3-mercaptopropanoic acid or R-cysteine, but industry shortens to ‘Cysteine’ for simplicity. On food ingredient lists, it might show up as E920 or "flour treatment agent." Pharmaceutical bottles list it as L-Cysteine hydrochloride or, for the modified version, N-acetylcysteine. This wide array of names points to its ubiquity across practices, with each label designed to match regulatory or functional context.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety for L-Cysteine depends on precise handling. Direct exposure should be avoided, since skin contact or inhalation can irritate sensitive individuals. Material Safety Data Sheets outline industrial hygiene rules—proper gloves, protective goggles, adequate ventilation, dust control. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EFSA have set limits for dietary intake and approve its use as a food additive. Companies need robust quality systems to track every shipment’s chain of custody, contamination risks, and responses to recalls. GFSI, ISO, and GMP certifications come into play for customers concerned about supply chain transparency and product reliability.

Application Area

Bakeries welcome L-Cysteine as a dough conditioner that speeds up mixing and improves pan flow. Packed food makers use it to preserve color in fruit and vegetable products. Medicine taps L-Cysteine for its mucolytic properties, helping break up mucus in patients with respiratory issues. Some use it as a building block in parenteral nutrition for patients who cannot feed via the gut. Personal care brands work it into perm solutions for hair, thanks to the protein-disrupting action. Animal feed makers apply it for its role in producing taurine, crucial for some pets. Even biotech labs use the compound for protein sequencing and cell culture supplements, showing that few industries fail to touch L-Cysteine at some stage.

Research & Development

Cutting-edge research points to L-Cysteine’s role in anti-aging, cancer therapy, and neuroprotection. Teams are exploring how it enhances glutathione levels, supporting cell defense systems against oxidative stress. Synthetic biology pushes boundaries by engineering improved microbial strains, tweaking metabolic pathways to boost efficiency, reduce byproducts, or alter downstream modifications. Computational chemists model interactions with drugs and proteins, aiming for better-targeted therapies. Scientists monitor cysteine’s behavior in protein folding diseases, autoimmune disorders, and rare genetic conditions. Every year, new studies add to the understanding—each project showing just how central a single amino acid can be across health and technology.

Toxicity Research

Animal and human testing show that too much L-Cysteine can harm. High doses may lead to nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, while even moderate levels can interact with certain prescription medications (most notably, those affecting sulfur metabolism). Early animal studies identified neurotoxic effects at extremely high concentrations. Regulatory bodies collect this evidence to set admissible daily intakes and to watch for evidence of long-term harm, especially as the compound becomes more common in supplements and specialty foods. Most safety concerns circle around the modified forms or byproducts produced during storage, not the natural amino acid at practical doses.

Future Prospects

Amino acid science keeps pointing to new applications for L-Cysteine. Demand for clean-label, animal-free, or nature-identical ingredients rises in tandem with global food trends, pushing biotech even further. Big players in pharma expect better antioxidant therapies, driven by the molecule’s unique reactivity. Personalized nutrition and molecular medicine may soon tailor dosing to individual genetic makeup, opening markets the raw ingredient never reached before. As research maps its broader physiological roles—in immunity, cognition, detoxification—the portfolio will only grow. Smarter production technologies could cut costs, improve safety, and deliver on ethical sourcing, making L-Cysteine a name that bridges tradition with the momentum of modern science.

What is L-Cysteine used for?

Behind the Label: What Is L-Cysteine?

L-Cysteine pops up in a surprising number of places—bread, pizza dough, even some medicines. It's not an ingredient most people think about when pulling dinner from the oven or swallowing a pill, but it plays a steady role in modern food and pharmaceutical industries. It’s an amino acid that our bodies need but only make in small quantities. Most folks get it from protein-rich foods, but manufacturers use it in ways most wouldn’t expect.

Helping Hands in Food Production

Baking bread at home sometimes feels like a wrestling match with stiff dough. Commercial bakeries don’t have time for that hassle, so they turn to L-Cysteine. Adding it to dough softens the gluten, which turns a dense loaf into the sandwich bread we see at every grocery store shelf. It helps dough stretch and rise, which means bread comes out light but strong enough to hold up a thick layer of peanut butter. Food companies value reliability, and using L-Cysteine keeps every loaf with the same texture batch after batch.

It’s the same story for mass-produced pizza crust, buns, and bagels. People expect their food to look and feel a certain way every time. L-Cysteine delivers that consistency, especially with breads that need to survive shipping and long shelf lives. Although it hasn’t sparked the debate that, say, artificial flavors have, some shoppers do worry. L-Cysteine from natural sources often comes from feathers or human hair, which sounds off-putting if you haven’t read up on food chemistry. Thankfully, synthetic versions from fermentation have become more popular, lowering these concerns and making the process more transparent.

Pharmacy Shelves and Supplement Bottles

Unlike some food additives that only work in the kitchen, L-Cysteine earns its keep in hospitals and pharmacies, too. As a supplement, it supports the body’s natural defenses by fueling the production of glutathione—an antioxidant vital for keeping our cells healthy. Doctors sometimes turn to L-Cysteine in the form of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which cuts through thick mucus and gives relief to people struggling with chronic lung diseases. There’s also growing interest in NAC for mental health and liver protection after certain poisonings.

Decades of research back these medical uses. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration has given the nod to NAC for specific treatments, showing trust in both safety and effectiveness. As always, consulting a healthcare professional before starting a supplement remains the best route. Too much L-Cysteine can tip the scales and cause unwanted side effects—nausea, cramps, and too-low blood pressure in rare cases.

Keeping an Eye on Safety

Regulators worldwide monitor L-Cysteine closely. Food producers must obey clear rules about sourcing and labeling. Efforts continue to find more plant-based and microbial sources, which should cut worries about animal welfare and religious dietary restrictions. As the demand for clean, transparent food grows, companies face real pressure to explain where every additive comes from and why it’s there. With more consumers paying attention, the move toward fermentation-based L-Cysteine looks like a win for both safety and peace of mind.

Looking Ahead

Once you know how much food science goes into something as ordinary as bread, it’s hard not to look at the ingredients list with fresh eyes. L-Cysteine earns its place in recipes and pharmacy cabinets by making food and medicine work a little better. As production methods improve and transparency increases, there are more reasons for consumers to trust what’s inside—and more chances for meaningful conversations between companies, shoppers, and health experts about what goes into our food and bodies.

Is L-Cysteine safe to consume?

Why L-Cysteine Pops Up On Food Labels

Eating packaged bread in many countries, shoppers sometimes catch a glimpse of L-Cysteine listed in the ingredients. Bakers grab it to soften dough and keep rolls fresh a bit longer. Fast food chains and supermarket bread brands often use it for consistency in texture. Industry has leaned on this amino acid for decades, and the source has evolved over time.

Understanding What Goes Into L-Cysteine

Most folks know that protein foods—think chicken, eggs, dairy—supply amino acids, including cysteine. L-Cysteine acts as a "building block" for the body, helping form protein itself. In the food industry, it's made through different means. Years ago, factories relied mostly on hair and feathers, usually from poultry, to extract it. People who avoid animal products found that hard to swallow.

Today, more companies rely on a fermentation process. This method lets them use corn or other plant sources, pleasing those looking for a vegetarian or vegan diet. Food safety agencies keep tabs on production methods so any L-Cysteine hitting supermarket shelves comes from a controlled source and meets purity standards.

What Science Says About Safety

Digging into the science, L-Cysteine doesn’t stir up many red flags. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) both agree it carries no big health risk at the low doses found in foods. The FDA slots it under the “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) label, meaning any amount used in food follows strict safety limits.

L-Cysteine already lives in the body and plays a key part in making glutathione, the body's own antioxidant. That antioxidant shields cells from damage daily and keeps the liver in shape. Food sources of cysteine—like poultry, eggs, dairy, and some vegetables—don’t set off any alarm bells for healthy people.

People with rare inherited conditions like cystinuria, which affects how the body handles certain amino acids, do need to watch their intake. For nearly everyone else, eating bread or pizzas that list L-Cysteine brings no added safety issues compared to any other amino acid in the diet.

Concerns and Being Honest With Shoppers

People who keep strict kosher, follow halal rules, or stick to a vegan diet sometimes worry about the source of L-Cysteine. Ingredient lists don’t always tell you much about how a compound gets made. Here’s where clear labeling helps. Some companies started flagging “vegan L-Cysteine” to avoid confusion. Smart shoppers can also check with bakers or food brands about the source if it really matters personally or ethically.

Microbial fermentation now covers a rising share of today’s L-Cysteine market. Standards in food production offer reasonable assurance, but until every company switches to non-animal sources, a little vigilance on the consumer’s part makes sense.

How To Keep Ingredients Transparent And Safe

Regulators and food scientists can do better in making sure consumers know where their food additives come from. Those who want to avoid animal products should have full access to that information. The push for clean labeling already fuels change: more companies look for plant-based and fermentation-derived options.

Companies can add short notes on packaging or on their websites about their ingredient sources. Honest marketing adds trust, and a smarter food system grows from open communication.

What are the side effects of L-Cysteine?

Looking Closer at L-Cysteine

L-Cysteine pops up in everything from nutritional supplements to common foods. It’s an amino acid, part of the building blocks the body uses to make proteins. Some people seek it out for hair growth, improved skin, or even for boosted energy. Others swallow it because they saw it on a label or read about its supposed benefits online. With something this common, it’s easy to forget there can be drawbacks.

Possible Digestive Issues

Stomach problems come up more than most people expect. Nausea, bloating, or stomach cramps can crop up in people taking supplemental L-Cysteine. Most healthy adults who eat a varied diet already get enough cysteine from foods like poultry, yogurt, oats, and eggs. Extra amounts, especially from powders or pills, can trip up the gut. I’ve noticed this after trying protein powders with extra L-Cysteine: the gassy, unsettled feeling stays for hours.

Risk of Allergic Reactions

Allergies can sneak in. Some commercial L-Cysteine is made from feathers or even extracted from hair. Anyone with allergic sensitivities—or anyone who keeps a vegan or kosher diet—might react to certain forms. The FDA lists L-Cysteine as generally recognized as safe, but “safe” doesn’t mean allergy-proof. Severe reactions are rare, but things like skin rashes, itching, or swelling may signal a problem, and stopping immediately becomes the smartest move.

Impact on Kidneys and Liver

Large doses over long periods can tax the kidneys or liver. These organs break down amino acids. Extra work stresses them, especially for those living with chronic conditions or taking other medications. Mild headaches, unexplained fatigue, or changes in urination deserve attention. A study from the National Institutes of Health pointed to the risk of kidney stones in people consuming excess amino acid supplements, including L-Cysteine. No pill or powder sits above common sense—moderation helps, and medical advice matters.

Changes in Blood Pressure

A few reports link L-Cysteine with drops in blood pressure. The mechanism isn’t fully mapped out in humans, but in animal trials, high doses affected blood vessels, relaxing them and bringing numbers down. Anyone managing low blood pressure or on blood pressure meds has reason to discuss this with a healthcare provider before trying a supplement.

Mood and Neurological Effects

Some evidence suggests high doses may influence mood or cause headaches. L-Cysteine participates in the body’s glutathione production, acting on brain chemistry and the nervous system. People with a history of mood disorders or migraines might want to avoid high-level supplementation. A 2018 review published in “Nutrients” pointed out cases of irritability and headache with amino acid overuse.

What Works Better

Stick to whole foods: chicken, sunflower seeds, lentils, and eggs cover your cysteine needs. Athletes or those recovering from surgery sometimes need more, but most healthy eaters already hit the daily target. If you’re tempted by supplements, check with your primary care provider and ask about your actual levels and medical history. Look for products with transparent sourcing—synthetic or plant-based cysteine tends to be cleaner and avoids animal-allergen risks.

Staying Safe

No supplement should promise the world or mask deeper health issues. Trusting food and moderation works for most of us. If something feels off—skin, stomach, mood—dial back and ask for help. The body recognizes what it needs, and chasing more doesn’t always help.

Is L-Cysteine suitable for vegetarians and vegans?

What Is L-Cysteine and Where Does It Come From?

L-Cysteine shows up on the label of many foods, from baked goods to supplements. This amino acid helps dough condition and extend shelf life, so manufacturers rely on it for everything from sandwich bread to commercial pizza crust. It seems harmless on the surface, but a closer look at where this ingredient comes from might surprise shoppers. For a long time, much of the L-Cysteine on the market came from human hair and poultry feathers. Hydrolyzing these sources produced the amino acid efficiently and cheaply, but the idea of eating something derived from hair or feathers doesn’t sit well with most people who care about how their food is made.

Vegetarians and vegans—at least the ones I know—often try to avoid animal-derived ingredients, not just obvious ones like meat or eggs, but the hidden stuff that sneaks into products. Although L-Cysteine sounds like something out of a chemistry set, its origins trace back to animal leftovers in a lot of cases. Even folks who have been living plant-based for years sometimes get caught off guard when they learn their favorite bagel might contain an ingredient that came from a chicken processing plant.

Vegetarian and Vegan Alternatives

Some manufacturers have listened to consumer demands and begun producing L-Cysteine through fermentation using plant sources, like corn or sugar. Companies like Ajinomoto and Wacker have moved in this direction, responding to ethical and religious dietary concerns. Using a fermentation process keeps the ingredient off the animal supply chain, making it clear for vegetarians and vegans to consume.

The problem comes with transparency. Not all product labels state the source of L-Cysteine. I’ve reached out to bakeries before, looking for a clear answer, but some suppliers won’t disclose whether their version comes from animal byproducts or microbial fermentation. This lack of visibility pushes people to become amateur detectives, diving through emails and websites, hoping to connect the dots and figure out if what they’re eating aligns with their values.

Why This Matters

Choosing food that matches your beliefs shouldn’t feel like a scavenger hunt. According to Mintel research, plant-based eating isn’t limited to vegans anymore—flexitarians, people with allergies, and those concerned with animal welfare have ballooned demand for transparency. The Vegetarian Society and Vegan Society both state that L-Cysteine coming from animal feathers or hair does not fit their definitions. Religious groups pay close attention too since L-Cysteine from non-halal or non-kosher animals raises big concerns for Muslim and Jewish communities.

I’ve seen shoppers put back items, frustrated because they couldn’t get a clear answer on the source of a single additive. That confusion erodes trust in brands. Consumers want to support ethical practices, but complex supply chains and vague labels just make people feel left out of the loop.

Better Solutions Are Possible

Clarity on ingredient sourcing can make a big difference. Some store brands have started labeling L-Cysteine as “vegetarian” or “vegan source,” which helps. Pushing for third-party certification—like vegan logos or kosher and halal stamps—could take the guesswork out of shopping. Companies willing to list exactly where their ingredients come from set themselves apart, winning loyalty and trust from a growing share of people who want more out of their food than empty calories. It shouldn’t be radical to want bread free from surprises. With enough demand, more brands could commit to only using plant-based or fermentation-derived L-Cysteine, making life easier for everyone who reads the fine print.

How much L-Cysteine should I take daily?

Why People Look to L-Cysteine

L-Cysteine grabs attention for its role in building glutathione, a powerful antioxidant in the body. Folks hoping to boost detox pathways or strengthen hair and skin often eye supplements or foods rich in this amino acid. Some gym-goers swear it helps their recovery, while others mention immune support. Sounds pretty useful, but before tossing a big bottle in the cart, it’s worth asking: how much does the body actually need?

Understanding Typical Needs

Most healthy adults get enough L-Cysteine from daily meals. Poultry, eggs, dairy, garlic, and beans all contribute. For someone eating a mixed diet, total cysteine intake—usually grouped with methionine—hovers around 250-300 milligrams per day, based on guidance from the Institute of Medicine. Unless someone is on a strict vegan diet or facing specific metabolic issues, deficiency doesn’t show up often.

Recommended Amounts in Supplements

People tend to look at supplements for an extra kick. Most commercial doses range from 250 mg up to 600 mg per pill. Clinical studies sometimes use higher doses, but that’s mostly under medical supervision. In my own dabblings with supplements, I stayed below 600 mg daily—which checks out with many safety reviews. Too much can cause digestive upset or even raise the risk for kidney stones, so more isn’t always better.

Exceptions: Who Should Pay Closer Attention?

Some specific groups have different needs. People with chronic conditions—HIV patients, for example—might benefit from higher intake, but doctors usually handle dosing. Folks with cystinuria or other amino acid processing problems have to watch intake carefully, since their bodies struggle to get rid of excess cysteine and related compounds. Anyone with liver or kidney issues is also better off skipping supplements or getting a green light from their physician.

Shortcuts Don’t Replace Real Food

Snagging nutrients from whole food delivers more overall benefits than a pile of isolated powders. Food brings in fiber, micronutrients, and healthy fats that all work together. If someone decides on a supplement, picking a reputable brand (US Pharmacopeia or NSF label) lowers the odds of contamination or mislabeling—something third-party testing keeps in check. That’s one lesson I learned after chasing cheap deals online: sometimes the price is low because quality control is out the window.

Risks of Overdoing It

L-Cysteine earns its “generally safe” label at typical doses, but too much can bring on headaches, gastrointestinal distress, and unpleasant sulfur burps no one wants to talk about. Large doses over time haven’t been well-studied. Animal experiments show possible heart risk and blood pressure spikes at extreme levels. As much hype as some internet gurus spread, there’s no shortcut past basic science or common sense.

Smart and Safe Use

One thing I keep in mind: the “more is better” rule almost never applies to amino acids outside medical care. Most folks already get what they need from a balanced diet. If a supplement feels necessary, checking with a health provider—and not just a sales clerk— makes the most sense. For most people, the 250-600 mg per day range lines up with safety and science.

Practical Steps

Anyone curious about their own intake can use food-tracking apps or consult a registered dietitian. Eating a variety of protein-rich foods usually covers the bases, no pill required. If there’s still concern, start with the lowest supplement dose and watch how the body responds.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2R)-2-amino-3-sulfanylpropanoic acid |

| Other names |

Cysteine L-2-Amino-3-mercaptopropionic acid L-β-Mercaptoalanine L-Cys |

| Pronunciation | /ɛl ˈsɪsˌtiːn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2R)-2-amino-3-sulfanylpropanoic acid |

| Other names |

Cysteine 2-Amino-3-mercaptopropanoic acid L-Cys Cysteinum L-2-Amino-3-mercaptopropanoic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ɛl ˈsɪsˌtiːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 52-90-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 17192 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17561 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL430 |

| ChemSpider | 581 |

| DrugBank | DB00120 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.034.430 |

| EC Number | 3.1.3.18 |

| Gmelin Reference | 8482 |

| KEGG | C00097 |

| MeSH | D002999 |

| PubChem CID | 5862 |

| RTECS number | MD0346000 |

| UNII | 6M070RFN67 |

| UN number | UN2969 |

| CAS Number | 52-90-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3539539 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17561 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL430 |

| ChemSpider | 589 |

| DrugBank | DB00141 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.027.451 |

| EC Number | 3.1.3.3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 37721 |

| KEGG | C00097 |

| MeSH | D:Cysteine |

| PubChem CID | 5862 |

| RTECS number | MD9646009 |

| UNII | 96K6UQ3ZD4 |

| UN number | UN2969 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5023782 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2S |

| Molar mass | 121.16 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Slightly unpleasant, sulfurous |

| Density | 1.3 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -2.5 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 8.14 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.3 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -33.0 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.672 |

| Dipole moment | 5.1560 D |

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2S |

| Molar mass | 121.16 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Faint odor of hydrochloric acid |

| Density | 1.3 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble |

| log P | -2.5 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa1 = 1.71, pKa2 = 8.33, pKa3 = 10.78 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.3 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -36.4×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.717 |

| Viscosity | 60 to 70 mPa.s |

| Dipole moment | 13.118 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 86.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -480.0 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -462.3 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 86.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -528.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2076 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA01 |

| ATC code | A16AA01 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P271, P272, P273, P280, P301+P312, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P304+P340, P312, P321, P330, P332+P313, P337+P313, P362+P364, P403+P233, P405, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | > 86 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 260 °C (500 °F; 533 K) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 1890 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50: 1,890 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | MI9100000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 50-150 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 100 mg/m3 |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P261, P305+P351+P338, P264, P337+P313, P280 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | > 192°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 260 °C (500 °F) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD₅₀ Oral - Rat - 1,890 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Mouse oral 1,200 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | RR0600000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 - 50 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 100 mg/m3 |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Homocysteine Cystine Methionine Glutathione Cysteamine |

| Related compounds |

Cystine Cysteine hydrochloride Homocysteine Glutathione Methionine N-acetylcysteine (NAC) |