Isoleucine: A Down-to-Earth Dive Into a Key Amino Acid

Historical Development

In the early 1900s, scientists identified isoleucine as one of the building blocks for proteins in living things. Over time, research teams began isolating isoleucine from natural protein sources through careful hydrolysis, uncovering its role in muscle growth, repair, and metabolism. Decades rolled by, and the amino acid made its entrance into commercial supplements and clinical nutrition, making it easier for athletes, patients, and the general population to access something the body only gets through food. Each step in the development shows a steady rise in understanding and demand, sparked by keen observation and relentless experimentation. This path reflects a familiar pattern seen with key biochemicals: focus shifts from simple curiosity to practical, life-changing uses as soon as technical capabilities catch up with need.

Product Overview

Isoleucine stands as a branched-chain amino acid, grouped with leucine and valine due to their similar effects on muscle tissue and energy levels. Dry, white, and crystalline, isoleucine carries an earthy, slightly bitter taste, unmistakable in many supplement powders. In the health and fitness industry, isoleucine shows up in recovery formulas and meal replacements, aiming to spur repair and fuel hungry cells. Medical fields use its pure form in intravenous solutions for patients who cannot eat solid food. Some food manufacturers slip it into nutrient blends, rounding out dietary profiles for children, seniors, and folks dealing with chronic illness. These uses do not just follow trends; they respond to real, well-documented nutritional gaps present in daily diets.

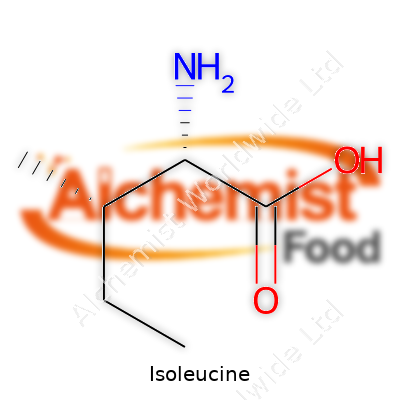

Physical & Chemical Properties

As an essential amino acid, isoleucine carries the chemical formula C6H13NO2. It comes as a white, crystalline powder, dissolving slightly in water but not in alcohol or ether. Isoleucine melts at about 284°C, where it starts breaking down before it can truly liquefy. Its isomeric structure distinguishes it from its cousin leucine, a small shift in side chain giving it unique properties—like a hand fitting just a bit differently into a glove. This subtlety matters, because muscles respond to isoleucine in their own way, depending on how and when it gets delivered. Handling it requires controlled humidity and temperature conditions, since the powder tends to pull in moisture from the air. These properties set the playing field for scientists and manufacturers aiming to maintain quality in every batch.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Companies working with isoleucine follow stringent guidelines for purity, potency, and traceability. Content in supplement and nutrition blends usually hovers around 98% purity or higher, with strict thresholds for heavy metals and contamination. On labels, you see terms like “free-form L-isoleucine,” with dosages measured in milligrams or grams. Regulatory action by agencies such as the FDA or EFSA sets clear standards for what goes on the jar or the clinical bottle. Batch codes and expiry dates give healthcare professionals and consumers confidence that the product stays fresh and stable up to a certain point, not just thrown on a shelf and forgotten. Experience tells me consumers take these standards seriously, especially in health products that promise something as personal as muscle protection or energy recovery.

Preparation Method

Traditional methods for producing isoleucine involved extracting it from animal or plant proteins using acid hydrolysis and labor-intensive purification steps. Factory-scale production today prefers fermentation, deploying genetically engineered microbes that spit out high yields of pure L-isoleucine. This switch saw a real drop in costs and environmental impacts, eliminating the need for animal sourcing and reducing chemical waste. After fermentation, companies use filtration, crystallization, and drying steps to bring isoleucine to a form that meets both purity expectations and mass-market needs. Familiarity with industrial fermentation makes it clear how technical this process becomes, with even a small disturbance threatening the quality or volume of an entire production run.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In the laboratory, isoleucine undergoes transformations aimed at unlocking new potential uses or analytical techniques. Peptide synthesis often leans on protective groups to shield the reactive amino group, followed by careful deprotection. Some research teams fiddle with esterification and amidation, creating compounds for specialized nutrition or pharmaceuticals. Chemical modifications open doors to different rates of absorption, less bitter taste, or better solubility. These efforts reflect a growing confidence in manipulating amino acids for targeted benefits rather than just offering them up in raw, unmodified form.

Synonyms & Product Names

Isoleucine goes by a handful of names across markets and research settings. Most people recognize “L-isoleucine” as the one that matters for human nutrition, with “2-amino-3-methylpentanoic acid” as its systematic title. In supplements, companies may shorten it to “Iso” or list it simply within a blend of BCAAs (branched-chain amino acids). Hospital-grade formulas usually spell out the full name to avoid confusion. In chemical supply catalogs, you sometimes find older terms like “isoleucin.” Clear naming avoids mix-ups in both research and daily use, something that matters more than ever as the supplement world grows crowded and brand competition intensifies.

Safety & Operational Standards

Manufacturers stick closely to documented safety protocols—workers wear gloves, masks, and eye protection to prevent skin or respiratory exposure to the fine powder. Safety data sheets detail possible risks like mild irritation or allergic responses but stress that pure isoleucine used in typical clinical or dietary doses rarely causes problems for healthy adults. Factory operations must respect not just worker health but also product contamination risks, treating every production area like part of a cleanroom. I’ve seen first-hand how rigorous training and strict audits catch problems before they can snowball into recalls or consumer complaints.

Application Area

Isoleucine takes center stage in sports nutrition, helping athletes keep muscle function during intense training or recovery after injury. Doctors use it in parenteral nutrition formulas, providing support for patients in surgery, cancer treatment, or intensive care. Some food producers turn to isoleucine as part of nutritional fortification for at-risk groups, including older adults and people recovering from illness. Lab researchers study its metabolic effects, seeking new ways to manage diabetes, liver disease, or other chronic conditions where amino acid profiles go awry. In every field, the story follows a need: keeping people strong, speeding up recovery, or simply filling in nutritional blanks left by modern diets that tend to favor calories over nutrient density.

Research & Development

Scientific attention on isoleucine continues to pick up steam. Studies are digging into its roles in glucose uptake, fat metabolism, and regulation of energy levels. Research teams explore ways to optimize its use in combination with other BCAAs, fine-tuning ratios to deliver better outcomes for athletes or clinical patients. Analytical chemistry advances offer more accurate ways to measure its levels in blood and tissues, helping clinicians tailor nutrition to individual needs. Patents for new synthetic methods and improved product formulations reflect ongoing investment by both private firms and public research foundations, each building on decades of incremental progress and real-world feedback from users.

Toxicity Research

Most evidence points to isoleucine as safe for humans when taken as directed. High doses, far beyond what any supplement company recommends, create risks of stomach upset, increased nitrogen levels in the blood, and additional stress on kidneys, especially for people with underlying health conditions. Toxicological studies done in rats, mice, and cell cultures help set upper limits that regulators use to draw up warnings and recommendations for safe usage. In my experience, consumers rarely hit these danger points without layering on multiple high-dose sports products or ignoring labeling instructions entirely. Education and common sense go a long way here.

Future Prospects

Looking forward, isoleucine promises new applications as research uncovers its broader impacts on metabolism, inflammation, and disease management. Nutritional science keeps evolving as more people demand targeted supplements, functional foods, and custom nutrition plans matched to age, genetics, or activity levels. Labs keep searching for improved forms that dissolve faster, taste better, or integrate seamlessly into foods and beverages. Tech advances in fermentation and gene editing hint at the possibility of greener, cheaper, and more scalable production soon. Public health policy, clinical guidelines, and consumer trust all depend on a steady flow of new knowledge, supported by rock-solid safety and transparent communication from everyone involved.

What is isoleucine used for?

Hitting the Gym and Muscle Repair

Ask anyone lifting weights or chasing gains about critical building blocks for muscle, and isoleucine comes up right beside leucine and valine. These three work best together, but isoleucine stands out because of the role it plays in repairing tired muscles and fighting off soreness. Every time muscles tear during exercise, they get rebuilt with the help of isoleucine’s hand in protein synthesis. I’ve upped my intake during heavy training and noticed how much faster the bounce-back feels, especially after leg days that leave you crawling up stairs. Science checks out: studies show athletes supplementing with the branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) recover quicker and face less muscle fatigue.

Keeping Blood Sugar Steady

People talk a lot about sugar spikes, whether trying to avoid mid-afternoon crashes or looking out for diabetes. Isoleucine chips in by playing referee for blood sugar, helping the body use up glucose properly. It stirs the metabolic pot, turning up energy output and lightly supporting insulin. Researchers studying rats and humans have seen how isoleucine taken before meals keeps glucose from spiking too high, making it easier to stay sharp and steady between meals. It doesn’t replace medical advice for diabetes, but in my own family I've noticed that high-protein meals, rich in natural sources like eggs, always leave us feeling stable compared to high-carb breakfasts.

Immune Boost and Stress

Low immunity usually shows up as that run-down feeling or frequent colds. Isoleucine has a foot in the door of the immune system as well—it plays a small role in producing immune cells, especially under physical stress. During periods of heavy training, travel, or tough deadlines, my experience says immunity drops if I slack off a good diet. Isoleucine-rich foods like chicken, lentils, and soybeans show up in research tables for a reason. My doctor mentioned athletes burning through amino acids faster need to pay attention, or risk catching every office bug floating around.

Energy, Endurance, and Diet

We hear a lot about carbs and fats, yet isoleucine sneaks in through another door: it helps produce energy when the going gets tough, especially when glucose runs low on long runs or hikes. This amino acid helps recycle stored body fat into fuel, so it’s handy for endurance athletes. From personal treks in the mountains, bananas and trail mix only go so far—adding in a protein source helps keep stamina high in the second half of the day.

Isoleucine in Everyday Foods

Supplements are one way, but most folks get isoleucine from eating regular food. Eggs, fish, nuts, lentils, turkey, and cheese land at the top. People on plant-based diets sometimes struggle if meals get repetitive, so mixing things up with tofu or sunflower seeds covers the bases. The body can’t make isoleucine by itself, so what appears on your plate counts for a lot. Missing enough leads to fatigue, headaches, or sluggishness that can drag down motivation for work or exercise. Paying attention to what fills your grocery basket pays off down the line.

Balancing Your Intake

Like anything, more isn’t always better. Piling on amino acid powders beyond what a balanced diet provides can upset the balance and bother the kidneys, especially in people with existing issues. Not everyone needs extra, but folks fighting illness, older adults, and athletes may benefit from a closer look at their protein mix. Conversations with real dietitians—rather than social media trends—have set me straight and kept things simple.

Is isoleucine safe to take as a supplement?

What is Isoleucine?

Isoleucine shows up in protein powder ingredient lists and supplement bottles for a reason. It’s one of the nine essential amino acids, the ones the body needs but can’t make on its own. Anyone who’s familiar with bodybuilding, sports nutrition, or strict plant-based eating has probably come across the trio known as branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs)—leucine, isoleucine, and valine. These nutrients support the body’s need for growth, muscle repair, and energy.

The Role of Isoleucine in the Body

During long runs or demanding workout sessions, muscle tissue leans on branched-chain amino acids, including isoleucine, for energy. Isoleucine has a hand in hemoglobin production and blood sugar regulation too. Diets rich in meats, seeds, eggs, cheese, and soy usually offer plenty for most people, but supplement makers market capsules and powders loaded with BCAAs to athletes and those on low-protein diets.

Looking at Safety: What Science Says

Plenty of peer-reviewed studies and the U.S. National Institutes of Health note that standard dietary intakes of isoleucine rarely cause trouble. The Food and Nutrition Board set an estimated daily adult need at about 19 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. Most healthy adults eating enough protein-rich foods beat that mark without batting an eye. According to research in journals like the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, even athletes who supplement with BCAAs do not usually exceed levels that produce harm.

Swallowing a few isoleucine capsules above the daily requirement does not look risky for most grown-ups with functioning kidneys and livers. Trouble tends to show up when supplements eclipse 50 times the body’s daily need, leading to poor coordination or, in rare cases, burdening the kidneys. For anyone with metabolic disorders like maple syrup urine disease, extra isoleucine is out of the question and doctors must be involved.

Supplements: More Is Not Always Better

Supplement marketing creates the sense that more isoleucine means better performance. In reality, most well-fed adults, including gym regulars, already soak up everything they need from chicken, fish, cheese, and legumes. Extra BCAAs—of which isoleucine is a part—do little unless a person’s diet falls short or medical advice suggests supplementation.

No supplement takes the place of a solid, balanced meal. For instance, large doses of BCAAs with little leucine or valine (or without much dietary protein at all) can skew natural amino acid balance, which can create headaches, mood swings, or digestive trouble. Some people even notice nausea at high supplement doses.

Practical Solutions and Guidance

If you’re healthy, eat a balanced diet, and don’t have specific medical advice, there’s no pressing need to take isoleucine in isolation. Sticking with natural protein-rich foods leads to the right result for most people. If you train hard, have trouble eating enough, or follow strict diets, a registered dietitian or sports nutritionist can help figure out if supplements make sense—always considering any kidney or liver issues.

Reading labels closely protects against accidental mega-dosing. For kids, pregnant women, and people with chronic illness, doctors’ orders matter most. Manufacturers in developed countries follow tight rules to limit contamination, but spending the time to look for third-party tested products never hurts.

What are the benefits of isoleucine for muscle growth?

What Makes Isoleucine Stand Out?

Isoleucine belongs to the family of branched-chain amino acids, along with leucine and valine. Like its siblings, isoleucine is essential, meaning people must get it from food or supplements because the body can't produce it. Growing up playing sports and spending late nights after school at the gym, I heard plenty about protein powders and BCAAs. Yet, isoleucine took a backseat to leucine, even though muscle isn’t built on leucine alone.

Fueling Muscles, Not Just Building Them

Isoleucine acts as both a building block and a fuel source. During exercise, muscles break down BCAAs for energy. Among the three, isoleucine plays a significant part in creating this energy, which keeps muscles from feeling drained during long or intense training sessions. Less fatigue means keeping up reps and sets, and in my own workouts, those extra few minutes under tension have translated to new personal bests.

A study in the Journal of Nutrition noted that supplementing with isoleucine can reduce muscle breakdown and support recovery after tough exercise. Recovery shapes progress; skipping it puts people on the fast track to plateaus.

Blood Sugar and Protein Synthesis

Isoleucine stands out because it helps regulate blood sugar by upping glucose uptake into muscle cells. That means muscles get more fuel precisely when they demand it. I remember cutting weight for wrestling meets—energy feels scarce, and muscles beg for any help they can get. Isoleucine helped keep my stamina up even when calories got tight.

On the muscle growth side, isoleucine encourages protein synthesis. Protein synthesis repairs damage from workouts. Each repair job leaves muscle a bit stronger and more substantial. According to the American Journal of Physiology, BCAAs like isoleucine stimulate muscle protein growth in both young and old folks, which pushes back against age-related muscle loss. My grandfather took BCAA supplements in his seventies, and he outworked people decades younger.

How Much is Enough?

The average athlete won’t notice much change without hitting the right amount. Nutritionists recommend about 19 mg per pound of body weight. People running marathons or powerlifting may need a bigger dose. Chicken, eggs, fish, nuts, soy, and dairy hold plenty of isoleucine, so a varied diet covers most bases. Vegetarians sometimes fall short—supplements fill the gap for them.

Too much isn’t always better. Some research ties excess intake to imbalances that might hurt kidneys or mess with brain chemistry. Balance is key. A dietitian’s advice works best, especially for folks with health issues.

What Could be Improved?

Supplement companies love bold promises, but rarely offer a full picture. Beginners get fed the idea that more is better, when timing and whole-food sources shape results more consistently than scooping extra powder. There’s room for more education on how BCAAs work together, rather than spotlighting one while forgetting the value of eating a variety of proteins.

More research could shed light on the best diet combinations for older adults or those in rehabilitation. Doctors and trainers could discuss nutrition just as much as exercise routines. In my own fitness circles, coaches who focused on meal planning saw fewer injuries and better results than those who pushed supplements alone.

Takeaways for Everyday Training

Isoleucine doesn’t carry the flash of creatine or the brand name power of exploding protein tubs, but it quietly powers the kinds of workouts and recovery that make a difference. Smart planning, balanced meals, and conversation with real experts will always beat chasing after the latest supplement trend. For muscle growth and overall health, isoleucine deserves a spot on the plate, not just in the shaker bottle.

What is the recommended dosage of isoleucine?

Isoleucine’s Place in Nutrition

Every time someone talks about building muscle or recovering after a tough workout, amino acids enter the conversation. Among them, isoleucine often hides in the shadow of its better-known cousin, leucine. Still, isoleucine carries its weight for energy, endurance, and recovery. The question pressing for athletes, gym-goers, and health enthusiasts deals with how much is enough.

Why Isoleucine Matters

Our bodies can’t create isoleucine on their own. We must get it from food. We use it to support muscle tissue, regulate blood sugar, and even help our immune system. Diets low in protein, such as vegan or vegetarian plans, can leave folks scrapping for enough. That’s never just about looking fit—a lack of essential amino acids drags energy and may lead to muscle wasting over time.

Recommended Dosage: What the Numbers Say

A clear answer means looking straight at science. The World Health Organization suggests a daily intake for healthy adults of about 20 mg per kilogram of body weight. Somebody weighing 70 kilograms (154 pounds) would shoot for about 1.4 grams per day. These numbers cover folks getting their protein from standard meals, not from powders or pills.

For athletes, the needs rise, and some experts push closer to 48 mg per kilogram a day during heavy training, often bundled with other branched-chain amino acids in supplements. It’s rare for anyone to need more than this unless a doctor steps in and recommends it.

Too Much of a Good Thing?

Piling on amino acids sounds tempting, especially with the surge of fitness culture. Yet, flooding your system with more than you need means kidneys working overtime, potential imbalances, and wasted money on supplements that don’t move the needle on performance. Too much isoleucine can also mess with mood or produce headaches, based on clinical observations. No professional wants to see a patient sacrifice long-term health for a short-term boost.

Real Food: The Best Source

Eggs, chicken, tofu, lentils, and fish break the myth that supplements are always necessary. Most people eating varied whole foods will not fall short. Those who practice strict veganism should pay closer attention, but plenty of plant-based foods pack isoleucine. Edamame, tempeh, pumpkin seeds, and oats land high on the list. Using food labels and nutrition trackers makes sure intake meets daily needs without fuss or risk.

Who Should Check Their Intake

Some people face bigger risks than others. Older adults sometimes eat less protein, putting them at risk for muscle loss called sarcopenia. Young athletes chasing performance with restrictive diets may slip up and miss out. People with rare metabolic conditions, or recovering from serious injury, also have special considerations. Getting advice from a registered dietitian or a physician trained in nutrition is the safest bet for these groups.

Practical Solutions

For most, planning meals around protein-rich foods covers the bases. If there’s doubt, a health professional can recommend a simple blood test or diet review for extra peace of mind. Chasing after balance—rather than extremes—serves health best in every case. People can trust their bodies, but gut checks backed by nutrition facts always come out on top.

Are there any side effects of taking isoleucine?

Understanding Isoleucine’s Role

Isoleucine stands out as one of the branched-chain amino acids, right alongside leucine and valine. Bodies rely on isoleucine for more than just muscle growth. It takes part in repairing tissue, keeping blood sugar steady, and even in forming hemoglobin. Many know isoleucine from sports supplements and protein shakes. Labels sell promises of more muscle strength and support for athletic performance. Most healthy diets already bring in enough isoleucine through foods like eggs, fish, chicken, and beans. Folks who pack in balanced meals usually hit their daily target without paying extra attention.

Possible Side Effects – More Is Not Always Better

The world often tries to push the belief, “if a little helps, then more works better.” This thinking doesn’t apply to isoleucine supplements. The body works hard to maintain balance, and too much of one amino acid can disturb how the others get used. Excessive amounts of isoleucine stretch the liver and kidneys, sometimes forcing them to clean up after an overload. Some people start to notice headaches, fatigue, or a strange feeling of nausea. Others point to digestive problems, like bloating or stomach cramps.

Rare but real, very high doses have led to more concerning symptoms. These include severe allergic reactions, trouble breathing, and swelling. Some case reports reveal mental changes—confusion, mood swings, and loss of coordination—especially if someone with a rare metabolism disorder heaps on more isoleucine than the body can handle. Anyone with maple syrup urine disease, for example, faces danger when branched-chain amino acids climb too high.

Who Should Show Extra Caution?

Healthy adults, especially those eating a varied diet, do not need extra isoleucine from bottles or powders. People with chronic liver or kidney conditions get hit the hardest by isoleucine overload because their organs already face more strain. Athletes sometimes chase after bigger muscles or faster recovery, so it’s tempting to look for shortcuts in supplement form. That choice comes with risk, especially without professional advice. Pregnant and breastfeeding women also want to keep intake in check, as nobody really knows how much is too much for developing babies. Children and teens grow fast and might need more protein, but supplements rarely offer benefits they can’t get from food. For anyone thinking about adding new pills or powders, a chat with a doctor or registered dietitian brings peace of mind.

Smart Choices and Practical Steps

Supplements draw attention thanks to aggressive marketing and social media, but food holds more power for most people. Chicken, dairy, nuts, soy—these ingredients provide plenty of isoleucine in balanced amounts. Protein shakes cover a busy lifestyle, but taking extra powders without checking the label leads to accidental overload. Reading packaging, understanding daily protein needs, and staying mindful about portion sizes help keep things on track. It doesn’t hurt to ask a healthcare provider before starting any new supplement—especially if there are other medicines or health conditions in the mix.

Long-term health means more than building muscle fast or chasing athletic records. Quality protein, in the right doses, keeps bodies strong and organs working smoothly. Isoleucine stands as an essential piece of the puzzle, but taking more than needed rarely delivers extra rewards. Better to trust healthy habits and avoid unnecessary risks while chasing a strong and energized life.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-amino-3-methylpentanoic acid |

| Other names |

2-Amino-3-methylvaleric acid Ile |

| Pronunciation | /ˌaɪ.səˈluː.siːn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Amino-3-methylpentanoic acid |

| Other names |

Ile 2-Amino-3-methylpentanoic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˌaɪ.səˈluː.siːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 73-32-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 683 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:45522 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL27564 |

| ChemSpider | 5361 |

| DrugBank | DB00197 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.030.101 |

| EC Number | EC 2.6.1.42 |

| Gmelin Reference | 8219 |

| KEGG | C00407 |

| MeSH | D007519 |

| PubChem CID | 6306 |

| RTECS number | NI4375000 |

| UNII | VO59YN61J8 |

| UN number | UN3335 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2020091 |

| CAS Number | 73-32-5 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `isoleucine.pdb|model title=Isoleucine; wireframe on; spacefill off; backbone off; spin off` |

| Beilstein Reference | 17161 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:17215 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL16410 |

| ChemSpider | 5469 |

| DrugBank | DB00197 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.061.395 |

| EC Number | EC 2.6.1.42 |

| Gmelin Reference | 7148 |

| KEGG | C00407 |

| MeSH | D007519 |

| PubChem CID | 6306 |

| RTECS number | NL3640000 |

| UNII | F8C77G2TI4 |

| UN number | UN3334 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 131.17 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.94 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Moderately soluble in water |

| log P | -1.317 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.000236 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.36 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.72 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | −8.6×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.470 |

| Dipole moment | 1.1243 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H13NO2 |

| Molar mass | 131.17 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.293 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble in water |

| log P | -1.85 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.00224 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.36 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.68 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -8.2e-6 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.542 |

| Dipole moment | 1.7713 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 198.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | −750.7 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3540.9 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 143.5 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -907.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3566.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A11AA03 |

| ATC code | A11HA06 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P272, P273, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P362+P364, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | 214°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 400°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): 11,300 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50: 5,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| PEL (Permissible) | 100 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 20 mg/kg bw |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315, H319, H335 |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P262 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 1, Flammability: 1, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Flash point | Flash point: 208.6 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 355°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 5,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50 > 5000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | NIOSH=XT2975000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 50 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 1300 mg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Leucine Valine Norleucine Alloisoleucine |

| Related compounds |

Leucine Valine Norvaline Methionine Threonine Alanine |