Iron Porphyrin: History, Science, and Real-World Impact

Historical Development

Iron porphyrin's story began in the mid-nineteenth century, back when chemists struggled to make sense of nature's most vivid colors and critical molecules. Hemoglobin, with its deep red hue and ability to carry oxygen, started much of the curiosity. For decades, researchers worked to isolate the molecule’s core, noticing time and again that iron sat in a ring-shaped structure—the porphyrin ring. Early synthetic efforts in the twentieth century allowed scientists to craft simpler versions in the lab, pushing bioinorganic chemistry forward. I often think about how every big leap in medicine or catalysis owes something to these early pursuits. Crystallographers unlocked structural blueprints in the 1960s, and you can trace virtually every major hemoprotein discovery—a feat that made understanding natural and synthetic metalloporphyrins possible—back to those foundational decades. Today’s labs build on these roots, crafting iron porphyrin molecules that help illuminate questions in biochemistry, catalysis, and materials science.

Product Overview

Iron porphyrin holds a steady role in both research circles and applied industries. This molecule sits right at the intersection of biology and synthetic chemistry. As a synthetic analog of the many heme-containing enzymes out there, iron porphyrins spark interest for their versatility in catalyzing oxidations, storing and carrying gases like oxygen or nitric oxide, and mimicking crucial cellular processes. Chemists purchase and customize these molecules not just for basic science, but for uses in sensors, fuel cells, and even pollution cleanup. You’ll find that iron porphyrins frequently help model enzyme activity, supporting drug discovery, toxicology, and green chemistry.

Physical & Chemical Properties

Solid at room temperature, iron porphyrin crystals bring a metallic, often purplish-black hue. Their fascinating stability stands out, since the core iron atom binds tightly to the nitrogen centers of the porphyrin ring. This bonding supports electronic transitions responsible for intense absorption bands in the visible spectrum, especially the Soret band near 400 nm—a signature every spectroscopist learns to recognize. These molecules are soluble in organic solvents like chloroform, dichloromethane, and dimethyl sulfoxide, enabling easy study and modification in the lab. The central iron often shifts between oxidation states—(II) and (III) most commonly—allowing these compounds to shuttle electrons and promote reactions, just as they do in living cells.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers sell iron porphyrin with detailed technical sheets, usually specifying purity above 95% for research grades. Typical documentation mentions the molecular formula—C20H12FeN4 for simpler tetraphenyl derivatives. Suppliers report exact weight, a characteristic UV-Vis spectrum, melting point, and, sometimes, X-ray diffraction data when crystalline quality matters for advanced research. Every bottle needs labels displaying key hazard warnings, batch number, storage recommendations, and a unique catalog identifier. Accuracy matters—routine lab projects grind to a halt if the compound arrives outside stated parameters, or if the labeling skips crucial hazards tied to heavy metal exposure.

Preparation Method

Researchers most often build iron porphyrin through stepwise organic synthesis. Starting from pyrrole and aldehyde precursors, chemists fuse these rings through acid catalysis, laying out the backbone. Adding iron typically follows as the last step, where an iron salt like FeCl2 reacts with the freshly-prepared porphyrin in an inert atmosphere, letting metal ions insert smoothly into the macrocyclic cavity. Some groups explore greener alternatives—microwave-assisted methods, water-based systems, or solid-state pathways—to cut down on solvent use and reaction time. For those with less time or resources, commercial sources provide dependable, ready-to-use iron porphyrin in gram or kilogram scale.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Iron porphyrins show unique chemistry thanks to variable oxidation states and ligands. By choice of reaction partner, chemists coax these compounds to mimic a vast range of natural processes. Iron porphyrin can activate dioxygen, cleave hydrogen peroxide, or reduce nitrite, modeling heme enzyme activity down to the atom. Adding different peripheral groups—halogens, sulfonates, or carboxylates—tunes their stability, solubility, and reactivity, opening doors to custom catalysts or enzyme mimics. I’ve watched research teams master complex modifications, producing analogs that fight cancer in photodynamic therapy, tweak fuel cell performance, or scavenge pollutants. The ability to swap ligands or side chains brings these molecules a remarkable adaptability.

Synonyms & Product Names

Iron porphyrin wears several names, depending on the specific form and commercial source. Go-to synonyms in research include “hemin,” “ferriporphyrin,” “Fe-porphyrin complex,” and, in the case of synthetic types, “iron(III) tetraphenylporphyrin” or “FeTPP.” Chemical catalogs often add numbers, trademarked names, or abbreviations based on ligand structure. Proper naming avoids confusion—ordering the wrong analog can derail experiments, waste money, and introduce unforeseen safety problems.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safety requires unwavering attention, since iron porphyrins bring moderate hazards tied to heavy metals and aromatic chemistry. Lab-standard personal protective equipment—gloves, goggles, lab coat—remains non-negotiable. Since fine powder can pose an inhalation risk, researchers often weigh and transfer these compounds under a hood. Accidental skin or eye contact sometimes leaves stains, but the greater worries lie in chronic toxicity from mishandling or poor cleanup. Spills need immediate action using absorbent materials and proper disposal according to environmental and institutional rules. All waste streams demand careful segregation, especially since iron porphyrins resist easy environmental breakdown. Safe storage—dark, cool, with desiccant—keeps the solids stable and distinct from food or general supplies.

Application Area

Iron porphyrin’s reach crosses industries and academic fields. Biological modelers use it to decode enzyme mechanisms, offering molecular insight into heme-based proteins. Catalysis research harnesses these compounds to drive challenging oxidations or transformations under mild conditions, cutting down on waste and energy use in fine chemical production. Firms building biosensors rely on the molecule’s redox sensitivity, leveraging it to detect gases or toxins in breath, water, or even industrial exhaust. Environmental labs deploy iron porphyrin as a pollutant scavenger or diagnostic marker, tracing trace metals or organic toxins with pinpoint accuracy. In biomedicine, photodynamic therapy draws on their light-activated reactivity to target tumors precisely. Energy tech leans on these molecules, too—experimental fuel cells, artificial photosynthesis prototypes, and low-cost electrodes often use iron porphyrin to cut costs and boost efficiency.

Research & Development

Ongoing R&D into iron porphyrin stays vibrant thanks to its versatility. Collaborative teams race to decode how slight tweaks to ring structure change reactivity. Drug development circles probe iron porphyrin’s power to shuttle small molecules in living tissue, aiming to design smarter, more selective drugs. Materials scientists look to combine these molecules with conductive polymers, unlocking new classes of sensors, organic solar cells, and nano-scale devices. Universities and startups alike battle to lower costs and boost yields by inventing greener, more scalable preparation methods. I’ve seen entire research programs spring up around only a handful of synthetic tweaks—each one promising a new direction for sustainable chemistry or medical diagnostics.

Toxicity Research

Toxicity studies draw a clear line—while iron porphyrin mimics many natural processes, its intake outside designed protocols can bring real risks. Chronic exposure and mishandling linger as health concerns due to iron overload and potential oxidative stress. Studies show these compounds can disrupt metabolic pathways at high doses, especially in non-target organisms. Regulatory bodies weigh published data and demand strict limits for disposal and exposure, particularly in pharmaceutical and food research environments. Testing continues on the environmental impact, too, since degradation in soil and water remains slow, with persistence that raises bioaccumulation concerns. Proper education and vigorous lab discipline become non-negotiable in any work involving synthetic iron porphyrin derivatives.

Future Prospects

Iron porphyrin’s story moves forward with each new application and synthetic advance. Research priorities focus on more efficient fuel cell catalysts, lower-toxicity medical agents, and circular economy solutions for rare metal recovery. There’s energy around building single-molecule electronic devices—the ultimate in nanoengineering—by embedding iron porphyrin in molecular circuits. With the global focus on green chemistry and safer, more sustainable molecules, iron porphyrin’s flexible ring and redox versatility could shape next-generation materials, therapies, and diagnostic tools. Fresh discoveries tend to spark new questions rather than definitive answers, keeping the field dynamic and full of possibility for creative chemists and engineers alike.

What is Iron Porphyrin used for?

Iron Porphyrin at Work in Living Things

Iron porphyrin isn’t a household term, but its value is everywhere. At the heart of each red blood cell, there’s hemoglobin—a molecule built around an iron porphyrin ring. Without this, oxygen just wouldn’t get shipped around your body. It’s the iron atom right in the middle that grabs hold of oxygen. Every deep breath, every heartbeat depends on it.

Scientists have studied iron porphyrins for decades. The understanding started simple, but soon people saw patterns stretching into almost every living thing. Plants use a similar setup in chlorophyll, swapping out iron for magnesium to catch sunlight. Life leans on these structures more than most folks realize.

Not Just in Nature: Real-World Applications

Labs started to mimic what nature does with iron porphyrin. In medicine, researchers use it to build artificial blood substitutes. Some hospitals faced blood shortages and needed safer ways to transport oxygen in emergencies when blood donations fell short. Synthetic hemoglobin, built from iron porphyrin, stepped in. This holds promise for trauma care, war zones, and remote clinics.

Modern cancer research keeps circling back to iron porphyrins. Photodynamic therapy is one example: doctors use special molecules to build up in cancer cells. When light shines on the molecule, it activates, creating oxygen that can kill the cancer. Iron porphyrin acts as that trigger. Precision like this can protect healthy tissue, something chemotherapy drugs don’t always do well.

Chemistry and Clean Energy

Outside biology, iron porphyrins spark interest for cleaning up pollution. In water treatment, they break down tough toxins as part of chemical filters. They even help remove stubborn dyes in industrial wastewater, a big deal for textile factories dumping polluted streams into rivers. Recent studies show that these tiny structures can enable greener ways to pull carbon dioxide out of the air or turn it into useful chemicals, helping slow climate change.

Fuel cells run on clean hydrogen, promising a path past oil and coal. The problem: expensive materials like platinum are often required. Scientists have been swapping in iron porphyrin to speed up the reactions instead. If factories scale this up, clean cars and power plants could get a lot cheaper.

Real-World Barriers and Solutions

Nothing is as simple as copying nature and calling it done. Most of the breakthroughs need iron porphyrins in pure, stable forms, which isn’t always easy or cheap. There’s a constant challenge in scaling up ways to make these compounds without wasting resources. Pollution from chemical production remains a risk, so green chemistry has taken the lead role in many new projects, aiming for less hazardous waste.

Education stands as a hurdle. High school science skips over the details of how molecules like hemoglobin or catalysts work. Many bright students miss out on learning how these tiny structures keep everything running, from city hospital wards to energy grids. Pushing for stronger science classes and lab projects can give future chemists and doctors the tools to keep improving these designs.

Iron porphyrin looks simple under a microscope, but its real impact shows up in hospital rooms, power stations, and anything breathing the air. Scientists, educators, and policy makers need to keep finding new ways to put this molecule to use—for a healthier, cleaner, and more responsive world.

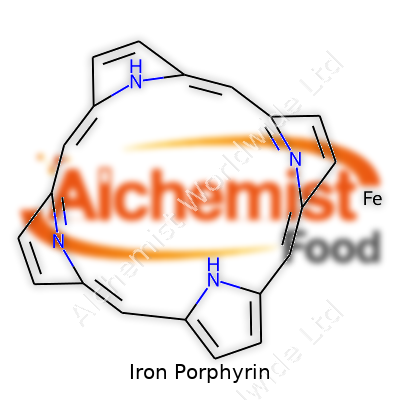

What is the chemical structure of Iron Porphyrin?

A Look at Iron Porphyrin’s Structure

Iron porphyrin brings together a combination of iron and a porphyrin ring, creating something unique in the world of chemistry. The porphyrin ring stands out as a broad, flat molecule, shaped by four smaller rings known as pyrroles. Picture four little boxes, each with a nitrogen atom peeking inward. These nitrogens set up the stage for the iron atom, gathering in a tight square that perfectly fits iron right in the center.

That flat ring forms a stable environment and positions the iron where it can interact with other molecules. The iron atom connects with all four nitrogens, creating a sturdy platform for what happens next. Two more spots on iron, sticking out from above and below the ring, stay open for business. These give iron its ability to latch on to other atoms or molecules, like water, oxygen, or even proteins.

Why This Structure Matters

Iron porphyrin gives us the backbone of hemoglobin and cytochromes in biology. Looking closer, the entire purpose comes from how the iron sits snugly inside the ring, anchored by nitrogens but always ready for more action. In hemoglobin, that central slot lets oxygen latch on, helping red blood cells haul life-giving O₂ around the body. Cytochromes, on the other hand, use iron porphyrin to shuttle electrons—fueling everything from burning sugar to muscle contraction.

The key thing is the flexibility of those open spots above and below the ring. Iron can slip between different oxidation states—Fe2+ and Fe3+. That lets it swap electrons with other molecules, a trick essential for metabolism. Without this central switchboard, living cells would struggle to turn food into energy. Research from Nobel laureate Dorothy Hodgkin and many after her made it clear: life dances to the tune of iron porphyrins.

Iron Porphyrin and Human Health

A clear illustration: take anemia caused by iron deficiency. Without enough iron, those rings inside our hemoglobin stay empty. Cells lose their grip on oxygen, fatigue sets in, and infections hang around longer. The structure of iron porphyrin helps explain why iron-rich foods—beans, spinach, and beef—can ease symptoms. Iron slides into porphyrin’s central spot, completes hemoglobin, and makes oxygen transport possible again.

Yet, there’s more than just nutrition. Modern medicine turns to artificial porphyrins, refining the structure and function in labs to mimic or even enhance natural ones. Researchers tinker with side chains on the ring, tweak iron’s neighbors, and watch how these changes shift electron flow. Some new drugs target diseases like cancer or malaria, where control over oxygen and electron transport matter most.

Facing Challenges with Solutions

A big issue comes up with environmental cleanup. Certain bacteria use iron porphyrins to breathe in places without oxygen, breaking down pollution in soils. Supporting this natural power could help restore damaged environments. Grants for research into engineered bacteria, which use iron porphyrin’s swapping skills, show promise for more efficient remediation. Collaboration between biologists, chemists, and engineers paves the way for safer, more productive use of these molecules.

Iron porphyrin’s chemical structure unlocks complex roles in both living systems and technology. With careful research, transparency in reporting findings, and steady collaboration, society keeps finding new ways to turn this chemistry into progress for health, energy, and the planet itself.

How should Iron Porphyrin be stored?

Why Proper Storage Protects Both People and Product

Iron porphyrin isn’t just another chemical. It stands at the core of countless research projects and is the backbone for studies in medicine, catalysis, and environmental science. Researchers have poured time and money into preparing or purchasing this compound, knowing contamination or degradation can sideline weeks of work. So, looking after it the right way matters a lot — not only for the science but also for everyone’s safety.

Know The Risks—And The Basics

Nobody wants to walk into the lab and find their iron porphyrin sample has faded or taken on a strange color. Most forms of iron porphyrin break down quickly under air, moisture, or strong light. From experience, storing metal-containing organic compounds like this in clear glass on an open bench usually means trouble. The iron core is likely to get oxidized if exposed. Air invites decay. Water in the air can also alter the structure, making samples unreliable for precision experiments.

These samples often come as fine crystals or powders. Left open or in poorly sealed vials, they can soak up atmospheric moisture or react with traces of oxygen. This reduces their shelf life and sometimes means lab teams have to start over, costing time and resources.

What Works: Tricks the Pros Use

It pays to transfer iron porphyrin to glass containers with airtight caps — I can’t count the number of times I’ve saved projects by scrupulously sealing samples right away. Parafilm helps, but a screw cap with a PTFE liner goes further. Stashing the vials in a desiccator never hurts, especially for long-term storage. These desiccators often contain silica gel or similar drying agents, keeping humidity away from sensitive powders.

For most of my colleagues, the next trick involves a glove box or inert gas. Laboratories equipped with nitrogen or argon glove boxes often store iron porphyrin inside. A regular deep freezer at -20°C offers a good solution for slow-down on chemical degradation, as long as the samples don’t experience wide temperature swings. Going colder — say, to -80°C — can sometimes help for very sensitive species, though most researchers get by at standard freezer temperatures.

Regular labeling and dating save headaches. Accidental swaps or confusion about batch age have ended narrowly a few times in shared labs. A clear label adds traceability and lets everyone know at a glance if a sample might have gone bad or was recently refilled. Keeping documentation matches E-E-A-T principles, too, giving users an opportunity to evaluate decisions based on real information.

Personal Experience: Safety Always Comes First

People forget how easily iron porphyrin stains hands and lab coats. Besides personal mess, these stains may indicate exposure to more serious risks. Inhaling powders or handling contaminated gloves poses health risks, and some breakdown products could be toxic. Training lab users, offering gloves, and keeping samples locked away go a long way in preventing accidents. Regularly checking storage areas for signs of leaks or compromised vials shows care both for people and inventory. No one likes arriving on a Monday morning to a spilled sample or a cloud of unfamiliar dust.

Better Storage, Better Science

Smart storage goes beyond keeping a sample from spoiling — it shields investments, prevents confusion, and keeps everyone safe. Decent glassware, airtight seals, low humidity, and cold storage all stack the deck in favor of success. By taking these steps, scientists ensure their iron porphyrin isn’t just intact, but ready for the next test, reaction, or breakthrough.

Is Iron Porphyrin hazardous to handle?

Iron Porphyrin: What Are We Dealing With?

Iron porphyrin sounds like something dreamed up in a chemistry lab, probably because that's where you'd find it. This compound forms a key part of hemoglobin, the molecule in our red blood cells that hauls oxygen around the body, and it also crops up in research or industrial settings. It's a popular tool in biochemical studies, environmental science, and sometimes in the push for greener catalysts.

It looks like a dark, red-brown powder and barely dissolves in water. So, what's the catch? Like many chemicals, its risks often come down to the way people handle it.

Hazard Profile: Real Life, Not Just Theory

Iron porphyrin isn’t known as a ‘supervillain’ chemical. You don’t hear disaster stories linked to it, but calling it safe across the board misses the mark. It’s classified as harmful if swallowed or inhaled at high enough doses, and large amounts could irritate the eyes, skin, or lungs. Its dust isn’t something you want drifting around in a workspace or floating into someone’s eyes.

People who work with iron porphyrin might not even consider its low-level toxicity, especially compared to heavy hitters like lead or mercury. That downplaying of risk sometimes leads to sloppy lab habits. I’ve seen workplaces take pride in glove use and good fume hoods, but every so often shortcuts slip in. Unlabeled containers, bags with broken seals, or powder visible on work surfaces send up red flags.

Respecting the Material Keeps People Safe

Anyone handling iron porphyrin owes it to themselves and their colleagues to treat it with respect, even if it doesn’t feature on every “dangerous substance” list. Goggles, gloves, coats, and a working ventilation system make a difference. It only takes a small lapse—like rubbing your eyes after handling the solid or leaving a sample uncovered—to create more risk than necessary.

Regulations from agencies like OSHA cover chemicals like this under general “hazardous materials” rules. Labs and manufacturers need an updated Safety Data Sheet at hand. Mixing it with strong acids or bases creates even more toxic problems, so understanding its chemistry closes some of the most obvious loopholes.

What Works: Common-Sense Protection

The best labs I’ve worked at keep things boring, and that’s a compliment. Daily routines focus on simple steps: weighing powders on spill trays, logging every gram, and mopping up spills without delay. Locking away the chemical when not needed keeps it out of reach for anyone who isn’t trained.

Medical concerns rarely pop up if folks use routine hygiene. Washing hands after a session in the lab matters more than many realize. Knowing the first aid plan pays off, even if it feels unnecessary until the day someone sneezes mid-transfer and gets a faceful of dust.

Solutions that Stick

Training new staff to know the hazards works far better than dry memos. Showing the right way to handle every step—from opening containers to cleaning up—cements safety as a habit. Posting instructions at the workbench sometimes says more than a fat binder in a back room.

There are no magic shortcuts. Small improvements, like switching to pre-measured capsules or single-use containers, cut back airborne dust. Reviewing safety protocols at least once a year helps spot bad habits before they become problems.

Iron porphyrin won’t make the evening news, but as with many chemicals, respect and routine keep trouble at bay.

What solvents can dissolve Iron Porphyrin?

What Is Iron Porphyrin?

Iron porphyrin carries a lot of weight in both research and industry. It’s the heart of hemoglobin and a big player in catalysis and environmental sensors. The molecule itself stays stubborn for chemists. Those four flat rings around an iron atom make it stable, but they also make it tough to get into solution. That holds experiments back and frustrates anyone who wants to analyze or make use of it.

Why Solubility Matters

I’ve worked with metal complexes that refuse to dissolve. Over time, you get a sense that choosing the wrong solvent means wasted time and wonky results. Solubility is more than a technical detail—it opens the gates to spectroscopy, crystallography, and chemical reactivity.

The Best Solvents for Iron Porphyrin

If you’re trying to get iron porphyrin into solution, organic solvents work better than water. Water won’t touch it—porphyrins often clump up and sink. Most chemists reach for nonpolar or slightly polar organic solvents first.

- Chloroform: Chloroform stands out as one of the classic choices. Dry chloroform breaks down the stacking between iron porphyrin molecules, teasing them apart. If there’s a little bit of heat, solubility goes up.

- Dichloromethane (DCM): DCM delivers similar performance to chloroform but can be more volatile. Its strong polarity gap works with both pure porphyrins and many of their substituted cousins.

- Tetrahydrofuran (THF): THF can help for porphyrins with bulky groups attached. It has enough polarity and can handle moderate concentrations, so I’ve seen success here in my own research when nothing else worked.

- Pyridine: Pyridine gets a reputation for “doing the job” with awkward molecules. It acts not just as a solvent but as a ligand. Pyridine can bind to the iron center, making certain porphyrin complexes more likely to dissolve. The downside: pyridine comes with its own smell and health concerns.

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) & Dimethylformamide (DMF): Both DMSO and DMF push the boundaries toward higher polarity. They work well for porphyrin salts, for those trying to do spectroscopy or electrochemistry. In my own experience, DMSO bathes everything in a sticky film, but sometimes you just need results.

What Gets in the Way?

Substituents on the porphyrin ring change solubility in dramatic ways. Bulky or hydrophilic groups coax these rings into DMSO or even methanol. Straight-up iron porphyrin, though, wants those chlorinated solvents. Purity matters too. Any leftover metal salts, acid, or water cause precipitation. I’ve had runs derailed simply because the glassware hadn’t dried thoroughly. Lab humidity can play tricks.

Risks and Handling

Some of these solvents, like chloroform and DCM, raise serious health flags. Labs must vent them properly, carry out work in the hood, and avoid skin contact. There’s also waste disposal—chlorinated solvents carry environmental and regulatory baggage.

Better Approaches?

Chemical modifications offer a safer route. Researchers sometimes add peripheral groups specifically to boost solubility in safer, greener solvents. It’s slower than grabbing a bottle off the shelf, but it can help reduce risks over the long haul. Using cosolvents, micelles, or even ionic liquids has gained attention, aiming to bridge the gap between chemical stubbornness and safety.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (17^2S,23^2S)-21,22,23,24-tetrahydro-6H,19H-porphin-5,10,15,20-tetramethyl-21,22,23,24-tetraazatetracyclo[12.8.0.0^{3,8}.0^{12,17}]docosa-1(14),3(8),4,6,11,13,15,18-octaene-6,19-diylideneiron |

| Other names |

Hemin Heme B Ferriprotoporphyrin IX Protohemin |

| Pronunciation | /ˌaɪərn pɔːrˈfaɪrɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | iron(2+);5,10,15,20-tetraphenylporphyrin-22,24-diide |

| Other names |

Porphine, iron complex Iron(II) porphyrin Heme model compound Iron porphine |

| Pronunciation | /ˈaɪərn pɔːrˈfaɪrɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 14655-77-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 0209363 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:60344 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1203132 |

| ChemSpider | 19630 |

| DrugBank | DB11536 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03d95035-4f6c-4943-8a16-7e08dd2ef3c4 |

| EC Number | EC 1.14.15.8 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin 16680 |

| KEGG | C00832 |

| MeSH | D011907 |

| PubChem CID | 16219994 |

| RTECS number | NO4564000 |

| UNII | VPVJ12F1LO |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID8035069 |

| CAS Number | [28733-50-6] |

| Beilstein Reference | 4147811 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:60344 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1241786 |

| ChemSpider | 5284886 |

| DrugBank | DB01860 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.131.533 |

| EC Number | EC 1.14.15.1 |

| Gmelin Reference | 59711 |

| KEGG | C00032 |

| MeSH | D011934 |

| PubChem CID | 6858075 |

| RTECS number | UJ7525000 |

| UNII | YW84JDZ5GW |

| UN number | UN1544 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2023526 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C44H28FeN4 |

| Molar mass | 616.489 g/mol |

| Appearance | Dark brown powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.2 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | insoluble |

| log P | 1.51 |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.8 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +58.8 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.5 |

| Dipole moment | 1.76 D |

| Chemical formula | C44H28FeN4 |

| Molar mass | 616.489 g/mol |

| Appearance | Dark brown powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | D=1.3 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble in water |

| log P | -2.4 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~4.9 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.9 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Paramagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.5 |

| Dipole moment | 2.72 Debye |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 218.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 120.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -621.0 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | B03AB05 |

| ATC code | B03AB05 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory and skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS06,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Danger |

| Hazard statements | H302 + H312 + H332: Harmful if swallowed, in contact with skin or if inhaled. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P261, P264, P271, P272, P273, P280, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P321, P332+P313, P362+P364, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | NFPA 704: 1-1-0 |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): >5000 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | IP2250000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 1 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 100 mg |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes skin and eye irritation, may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS06,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302 + H312 + H332: Harmful if swallowed, in contact with skin or if inhaled. |

| Precautionary statements | P261, P264, P270, P271, P272, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral) > 3,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral, rat: 1,000 mg/kg |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 50-100 mg/day |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Cobalt Porphyrin Manganese Porphyrin Zinc Porphyrin Copper Porphyrin Nickel Porphyrin |

| Related compounds |

Hemin Heme Protoporphyrin IX Zinc Porphyrin Manganese Porphyrin Cobalt Porphyrin Nickel Porphyrin |