Glycine (Aminoacetic Acid): A Detailed Commentary

Historical Development

People have been working with amino acids for a long time. Glycine caught the scientific world’s attention back in the mid-1800s, making it one of the earliest discovered amino acids. Chemists like Henri Braconnot picked it out while breaking down gelatin with hot sulfuric acid, noticing its simple structure compared to more complex molecules. Over the years, research around glycine advanced along with the growth of biochemistry, highlighting its role in proteins, nutrition, and broader chemical applications. In the early days, lab work depended on animal tissues and manual separation, but later, fermentation and synthetic pathways made production practical and scalable. Its journey from a curiosity to a common compound in labs and factories shows how something seemingly simple fits deeply into medicine, agriculture, food, and materials science.

Product Overview

Glycine, also called aminoacetic acid, forms the simplest building block among amino acids. It appears as a white, odorless, sweet-tasting powder, dissolving easily in water. This compound pops up naturally in proteins but also emerges through chemical or biological manufacturing. The demand for glycine comes from many places: feed for livestock, human nutrition, buffering solutions for labs, and raw materials for other chemicals. This broad usage keeps the market healthy and growing, proving glycine’s flexibility. Pharmaceutical ingredients and protein hydrolysate often include it, pushing the compound into everything from medicine to processed foods. Refined production methods ensure its purity fits health codes for direct ingestion or for uses in intravenous solutions and other sensitive products.

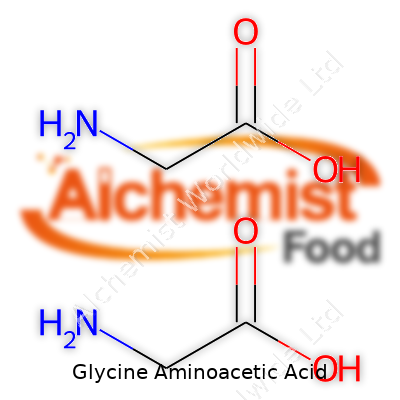

Physical & Chemical Properties

Glycine stands out for its basic structure: one amino group, one carboxyl group, and two hydrogen atoms attached to a simple carbon chain. Chemically, it’s represented as NH2CH2COOH. The compound’s melting point hovers around 233°C, after which it decomposes rather than turns to liquid. People handling glycine notice its low toxicity and mild sweetness, often describing its faintly sugary flavor after direct tasting in analytical work. In powder form, glycine dissolves well in water but not in organic solvents like ether or benzene. Dissolved in water, it acts as both a weak acid and weak base, making it useful in pH buffer systems for labs and industrial applications. Its zwitterionic form—holding both positive and negative charges—keeps it stable in a range of environments, explaining its popularity as a nutrient and a reaction medium.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Standards for glycine often draw from pharmacopeias and food safety commissions. High-purity grades for pharmaceutical uses demand tight control—over 99% purity with minimal levels of heavy metals, microbial contamination, and organic impurities. Technical grades for agricultural or industrial uses lean toward lower purity, but still need well-defined moisture and ash content. Manufacturers use international numbering and identifier systems, tagging glycine with names like E640 for food applications and specifying quality through batch testing and certificates of analysis. Labeling guidelines call for detailed concentration data, expiration dates, storage instructions, and handling precautions under Globally Harmonized System (GHS) safety rules. The presence of glycine in food or feed gets marked clearly, helping consumers and regulators alike trace its origin and safety information.

Preparation Method

The main roads to commercial glycine production split between chemical synthesis and fermentation. Synthetic manufacturing usually starts with monochloroacetic acid and ammonia, passing through a series of neutralization and recrystallization steps. This route works fast, with easy access to raw materials, and yields high purity once unwanted byproducts are separated. Another process ferments sugars using specific bacterial strains that convert carbohydrate material into glycine, fitting the trend toward greener, bio-based chemical production. Some industries recycle animal protein wastes, breaking them down enzymatically and isolating glycine, although demand for consistent purity limits this approach. Each method brings benefits: chemical synthesis delivers bulk at lower cost, while fermentation suits food and pharma needs where chemical residues and trace byproducts draw stricter oversight.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Glycine’s structure gives it versatility. It reacts easily to form peptides, joining with other amino acids to build proteins, peptides, and drugs. Chemists use it as a starting point for synthetic modifications—derivatizing the amino or carboxyl group to produce buffer salts, pharmaceutical compounds like glycine esters, and analogues that enhance its physical or biological traits. In organic synthesis, glycine often serves to create pH-specific solutions or occupies a role in the Strecker amino acid synthesis, an old but reliable way to assemble new amino acids. Its reactivity makes glycine a trusted tool for fine-tuning drug release rates, food preservation, and treating water. Breaking or assembling peptide bonds with glycine often shows up in industrial enzymatic processes, making the compound valuable for more than just direct ingestion.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll come across a handful of alternative names for glycine in research papers and safety data sheets. The most recognized is aminoacetic acid, though E640 pops up in food ingredient lists. In chemical trade, suppliers may refer to it as Glycol-aminoethanoic acid or even use the direct abbreviation “Gly,” especially in biochemical contexts. These synonyms help identify glycine across regulatory, scientific, and industrial databases, linking it with unique CAS Registry Numbers such as 56-40-6. While naming conventions differ by region or company, most buyers recognize that these variations point to the same underlying product, easing cross-border logistics and compliance audits for anything using glycine.

Safety & Operational Standards

Few people run into problems working with glycine, but sound workplace standards still matter. Safety data often lists glycine as low-risk, yet it’s always wise to avoid excessive dust or spillage. Standard lab gear—gloves, masks for powder handling, lab coats—helps keep working conditions safe. Storage guidelines call for dry places, tightly sealed containers, and distance from strong oxidizers. Ingesting typical amounts through diet or supplementation doesn’t cause trouble; only extremely high doses over long periods can set off metabolic issues, especially for those with existing kidney concerns. Facilities meeting ISO/cGMP quality control prove essential for eliminating impurities and keeping batches traceable during recalls or regulatory checks. Most global health regulators—FDA, EFSA, JECFA—rate glycine as safe, with studies and expert opinions backing real-world practice in laboratories, food plants, and pharmaceutical clean rooms.

Application Area

Glycine lands in some unexpected corners beyond nutrition. In food, people use it for its gentle sweetness and preservation effects, stabilizing processed products like sauces, broths, and canned goods. Animal feed blends it in as a protein source or taste enhancer, helping promote growth and feed conversion. Pharmacies turn to glycine in parenteral nutrition and oral supplements, counting on its gentle metabolic pathway for sensitive patients. Beyond that, glycine’s buffer action in biochemical assays keeps lab experiments reliable, particularly where small pH changes ruin delicate reactions. In metal cleaning and electroplating, glycine’s chelating effect makes it handy for surfacing and finishing jobs. Water treatment engineers select glycine for heavy metal removal, further broadening its utility. Everywhere glycine shows up, the common thread is reliability—steady chemical behavior, digestibility, and ease of mixing with other ingredients.

Research & Development

Researchers look at glycine through several lenses. Neuroscientists study how it manages neurotransmission, seeing benefits for treating conditions involving neural signaling. Clinical teams examine glycine for slowing muscle wasting in patients with chronic disease, and new work suggests anti-inflammatory roles that could help manage autoimmune diseases. Food science labs tinker with glycine as a seasoning and preservative, searching for dose ranges that maximize shelf stability without changing flavor profiles too much. Agricultural labs evaluate glycine’s impact on animal health, while industrial chemists test modified glycine derivatives for better performance in buffers and water treatment. All this research motivates improvements in both production and application: higher purity, more targeted effects in therapeutic formulas, and increased value for end-users across fields.

Toxicity Research

Toxicological tests show glycine rarely causes harm at realistic exposure levels. Human metabolism absorbs and processes glycine quickly, thanks to its role in the body’s normal function. Rats and mice tolerate high oral doses without significant health changes; similar findings translated into food and drug safety approvals worldwide. Some studies investigate long-term effects of very high intake on kidney function, but even here the evidence of lasting harm remains limited. The low allergenicity and absence of hazardous impurities in certified glycine puts it well below standard cutoff points for acute or chronic toxicity. That said, researchers still study glycine’s behavior in special populations—those with rare enzyme deficiencies, for example—ensuring its use stays grounded in careful data and updated safety protocols.

Future Prospects

Chances look good for glycine, both in basic science and commercial use. Growing demand for protein-rich animal feed and dietary supplements opens bigger markets, especially in regions pushing for food security. Pharmaceutical research teams imagine new drugs that combine glycine’s gentle profile with targeted therapeutic effects for pain, inflammation, and neurological diseases. Water purification and agricultural chemistry trends align with eco-friendlier, bio-based feedstocks, pushing research toward fermentation and green chemistry improvements in glycine manufacturing. Researchers eye advances in synthetic biology—engineering microbes for better yields or tailored derivatives—and digital modeling of glycine’s interactions for smarter, more sustainable product development. Glycine’s story shows how substance, not hype, pushes a simple molecule into so many lives and industries.

What is Glycine Aminoacetic Acid used for?

Hidden in Everyday Health

Glycine, often called aminoacetic acid, finds its way into a lot of things people use every day. Think of that protein shake you had after a tough workout or the broth used on a chilly night—glycine pops up in both. It isn’t just a building block for protein. It does heavy lifting in the body, showing up where you might least expect it. For example, hospitals rely on glycine solutions in procedures like bladder irrigations, making certain treatments safer for patients. Some people look for glycine supplements to boost sleep or balance blood sugar. This comes as no surprise to those who've dealt with stress or erratic sleep and noticed how certain supplements can make a real difference.

Touching Lives Beyond the Plate

In the world of food, glycine often goes under the radar. Food companies add it to some processed items to enhance flavor—a subtle sweet note without the calorie hit of sugar. For those who watch their diet carefully, it’s worth knowing that glycine doesn’t spike blood sugar levels like other additives. Based on clinical findings, glycine leads to milder glycemic responses, which appeals to folks monitoring diabetes or chasing stable energy. My own experience with metabolic rollercoasters has shown that tracking what goes into our food can help smooth out those rough patches.

A Quiet Player in Science Labs and Industry

Glycine also gets nods outside of nutrition. In labs, chemists trust glycine as a buffer. Experiments demand consistency, and glycine helps keep pH steady without clouding results. I remember my old college chemistry days—sometimes it takes something as simple as glycine to avoid expensive mistakes. Electronics makers, too, draw value from glycine during metal plating steps. They get smoother, shinier surfaces for connectors, which matters in our phone-obsessed world. This cross between health, research, and technology shows how interconnected modern life becomes—even the simple ingredients count.

Nerve Health and Brain Function

Few people realize that glycine also talks to the brain. It acts as a calming messenger, dialing down nerve signals. That impacts everything from muscle control to mood. There’s ongoing research into glycine’s potential for managing conditions such as schizophrenia and stroke recovery. Having supported a family member through cognitive rehab, these small discoveries mean hope for more tailored care. Safety always comes first—large doses aren’t risk-free—but anyone chasing better nerve or mental health could benefit from learning more about it.

Getting Glycine Safely

For most, a balanced diet easily covers glycine’s basics. Anyone eyeing supplements should talk openly with a doctor, especially if medications are in play. Supplements can have unexpected interactions—no one wants surprises when it comes to their health. If industry trends push for broader glycine use, tighter oversight gets essential, making sure quality checks aren’t skipped and that vulnerable groups stay protected. That includes regular review of sourcing, manufacturing standards, and clear labeling for consumers.

Looking Ahead

More eyes look at simple compounds like glycine for answers to everyday health problems. Research keeps racing forward, but the basics stick around—quality raw materials, honest advice from medical professionals, and keeping an eye on long-term effects. It’s a reminder that something humble like glycine can carry weight well beyond the lab bench or supplement shelf.

Is Glycine Aminoacetic Acid safe to consume?

Digging Into What Glycine Is

Some supplements grab headlines claiming all sorts of health benefits. Glycine, or aminoacetic acid, sits quietly on store shelves. It’s not a flashy “superfood,” but it plays a role in the way bodies work. This amino acid helps build proteins, supports metabolism, and plays a part in passing signals around the brain.

Plenty of folks get glycine through their diets without thinking about it. Meat, fish, dairy, beans—these foods supply more than enough for most people. Nobody really sits down to dinner listing off amino acids in their steak or tofu, but that’s where the body finds glycine without any fuss.

Safety Record in Supplements and Food

Over time, research has looked at glycine’s track record. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recognizes glycine as “Generally Recognized As Safe” for use in food. That’s a high bar—hard for any ingredient to meet since it means years of researchers and regulators checking the numbers. Clinical studies often test doses much higher than anyone would eat during a normal day. Even then, severe side effects show up rarely. Most commonly, reports include mild digestive issues at high supplemental doses—think stomach upset, nausea, maybe some soft stools.

Not all news sounds so reassuring. Some people have an underlying medical condition called nonketotic hyperglycinemia, where glycine builds up to dangerous levels. This is rare and genetic. For anyone without the disorder, evidence doesn’t suggest a risk of poisoning from eating foods with glycine or using supplements within standard doses.

Does Adding Glycine Bring Big Benefits?

Plenty of claims swirl online and in supplement shops—better sleep, sharper mind, healthier joints, even anti-aging. Science doesn’t always keep up with marketing. Some studies back up sleep benefits when folks take small doses before bed, usually in the 3–5-gram range. Other potential perks, like joint health and protection against certain age-related decline, need stronger evidence. For most adults, there’s little reason to take large doses unless advised by a health professional.

From personal experience, focusing on a balanced diet, rich in whole foods rather than chasing after individual amino acids, brings steadier results. Nutrition texts agree—a diet based on real food covers glycine needs for nearly everyone.

How to Use Glycine Safely

Look at the label before buying or taking anything. Glycine as a pure powder or capsule, with nothing extra thrown in, works for those who really want to try a supplement. It’s smart to talk with a healthcare provider, especially for people taking medication or managing chronic conditions. Certain drugs or conditions could interact in ways researchers haven’t captured yet.

Kids, pregnant women, and anyone with significant health issues should stick to food sources unless their doctor has another plan. Risks stay lowest when you avoid megadoses, watch for any new symptoms, and buy from companies sticking to safe standards. Broad agreement across different sources, including nutritionists and government agencies, backs this.

Aim for the Basics

Glycine flies under the radar compared to other hot supplements. Most bodies already know what to do with it—in meat, beans, dairy, or an occasional supplement. Chasing after big doses doesn’t mean big results. Focus on whole foods, stay skeptical of over-the-top product claims, and always loop in a real healthcare professional with worries. That approach stands the test of time, supplement craze or not.

What are the health benefits of Glycine Aminoacetic Acid?

Breaking Down Glycine

Glycine, sometimes called aminoacetic acid, is an amino acid found in everything from meat and fish to beans and leafy greens. While some people have only heard about amino acids at the gym, glycine quietly works in the background every day, doing more than most folks realize.

Why Glycine Matters for Your Body

Your body makes its own glycine but not always enough, especially as stress levels rise, sleep gets short, or healthy foods take a back seat. Glycine plays a starring role in making collagen, the stuff that keeps skin stretchy, joints moving, and bones strong. Without enough collagen, joints creak, skin sags early, and bones may turn brittle.

Glycine also helps build a neurotransmitter called GABA. GABA acts like the brakes in your nervous system, easing anxious thoughts and helping with deeper, longer sleep. One clinical trial with middle-aged adults showed people slept better and woke up feeling more refreshed when taking three grams of glycine before bed.

There’s more to glycine than sleep. Research suggests glycine supports liver health, especially for folks regularly exposed to alcohol or environmental toxins. The liver relies on glycine to make glutathione, the body’s master antioxidant. In one study, glycine improved liver function in people showing early signs of fatty liver disease—a problem more folks are running into as processed foods and sugar crowd into everyday diets.

Glycine, Metabolism, and Muscle

People trying to manage blood sugar may want to know that glycine seems to support healthy glucose metabolism. It appears to help insulin work better and, in some studies, has modestly lowered blood sugar markers. This may be why folks with metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes show lower glycine levels in blood tests.

For people who lift weights or work out, glycine supports muscle recovery. It soothes inflammation, rebuilds tissue, and can shorten the soreness zone between tough workouts. Recovery matters, whether someone runs marathons or just wants to play a game of pickup basketball on weekends without limping afterward.

Are Supplements Necessary?

It’s true, most people get enough glycine just by eating a mix of protein-rich foods. But certain groups—older adults, people fighting chronic stress, those on strict diets—sometimes fall short. Collagen-rich foods have fallen out of favor. Bone broth, gelatin, and “nose-to-tail” eating used to be common in kitchens. These days, they appear mostly during trendy food revivals.

Studies have tested glycine in supplement form, usually at doses of 3–5 grams per day. Trials have found this amount safe, without major side effects. Still, food remains the best foundation. Supplements can help fill gaps for some but can’t replace a balanced plate.

Getting Enough Every Day

For those aiming to up their glycine intake, think of classic foods like slow-cooked stews, chicken soup with bones, and even simple dishes like eggs and beans. Simple steps, like eating more diverse protein sources and adding the occasional spoonful of gelatin to recipes, can boost glycine intake without relying on pills.

Health always comes down to the basics. Glycine may not make headlines as often as other nutrients, but its steady, behind-the-scenes support helps people feel, look, and move better—day in and day out.

How should Glycine Aminoacetic Acid be taken or dosed?

The Basics Behind Glycine Use

Glycine isn’t some obscure compound. Our bodies make it every day. This simple amino acid crops up in foods like fish, meat, legumes, and dairy. Supplement aisles offer glycine as a single ingredient powder or mixed in blends. Those familiar with sports recovery, sleep supplements, or even general wellness routines probably recognize its name. Research over the years points to some tangible benefits: sleep support, calming the nervous system, and possible help with muscle repair.

How Much Glycine Makes Sense?

Figuring out how much glycine fits into a diet depends on the reason for using it. Most studies and nutritionists mention 1 to 3 grams daily for general health support. For more specific aims, such as managing sleep or metabolic issues, researchers often look at doses closer to 3 to 5 grams per day, and sometimes more for short-term studies. Heading far beyond this range isn’t a good idea unless under careful medical supervision.

The body already breaks down plenty of glycine from protein in food. As a supplement, high doses do not always mean better results. Sometimes, taking more than 10 grams at once can trigger loose stools or mild stomach upset. Some people, especially children, pregnant women, or those living with metabolic issues like kidney or liver disease, should talk to a healthcare provider before trying glycine supplements.

Timing and Form Matter

Some folks mix glycine powder in water, others blend it with tea or juice. Capsules work fine if the taste proves difficult, but the powdered form tends to cost less. Many prefer to take glycine in the evening because some studies suggest it might support better sleep or relaxation at night, thanks to its role as a calming neurotransmitter in the brain.

A single daily dose or splitting it into two servings both work for most adults. What matters is building a routine and watching for any unwanted effects. Pairing glycine with meals feels easier on the stomach for some. If the supplement ends up upsetting digestion or causing drowsiness during the day, moving it to a different time slot usually solves the trouble.

What the Research Says

Reliable studies have shown benefits, but they use a range of doses. In a 2012 Japanese study, people taking 3 grams before bed reported better sleep quality. Other researchers using 5 grams for several weeks saw mild improvements in blood sugar control. No strong evidence exists yet for taking mega-doses. I’ve seen friends and athletes try higher amounts hoping for a bigger boost, but the results rarely match expectations and just raise the risk of gut issues.

Starting Safely and Looking Forward

Anyone curious about glycine should start low. One gram feels barely noticeable but gives a sense of how the supplement agrees with the body. Gradually increasing the amount over days—without racing ahead—lets the digestive system adjust. If someone wants to use glycine for stress, sleep, or recovery, consistency over several weeks almost always works out better than chasing bigger numbers on the scoop.

Long-term studies still need to catch up. We know enough to treat glycine as a tool, not a miracle cure. Anyone juggling medications, managing chronic health conditions, or pregnant should check with a pharmacist or doctor first, since even common supplements can interfere with prescriptions or underlying illnesses.

Nature packs glycine into everyday foods. Those interested in supplemental glycine do best by starting slow, thinking through why and how to use it, and listening to body signals along the way.

Are there any side effects of Glycine Aminoacetic Acid?

Understanding Glycine in Daily Life

Glycine isn’t foreign to our bodies. It’s a simple amino acid, found in protein-rich foods like meat, fish, beans, and dairy. Our bodies make it on their own, too. With such a fundamental role in metabolism, building muscle tissue, and supporting nervous system function, glycine ends up in supplements and health drinks. The market is full of claims—from better sleep to muscle recovery—so questions about safety and side effects make a lot of sense.

Common Side Effects: Minor and Manageable

Most healthy adults handle glycine just fine, especially when sticking to amounts found in foods. Once people turn to supplements at higher doses, some folks notice minor issues. After all, anything taken in excess can throw the body off balance. Some people report digestive upset—nausea, loose stool, or stomach pain—usually after higher amounts. A few notice drowsiness, likely because glycine aids the body’s relaxation response. That’s part of the reason it gets pitched for sleep support. Headaches or a feeling of tiredness have come up, too, but they’re pretty rare.

Deeper Health Concerns and Who Should Watch Out

Anyone with kidney or liver conditions needs to tread carefully. The body relies on organs to process and clear excess amino acids. If kidneys or the liver aren’t working as they should, glycine supplements could lead to more trouble than benefit. Folks taking medications for mental health, especially antipsychotic drugs that impact NMDA receptors, need to talk to a doctor before using glycine, as it plays a role in those same pathways and could intensify or block medication effects.

What Research Says

Clinical studies on glycine safety tend to use doses from 1 to 3 grams daily. Most participants handle these levels well for weeks or a couple of months. A handful of studies have stretched this range to up to 15 or even 60 grams for specific cases, such as schizophrenia or metabolic disorders, but those always play out under medical supervision. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recognizes glycine as “generally regarded as safe” (GRAS) for use in foods, which means researchers haven’t found major safety issues at typical dietary levels.

Gaps in the Story

Long-term supplement use, especially at high doses, doesn’t have enough research. Pregnancy, breastfeeding, and use in children fall into the same gap. Most companies don’t suggest glycine supplements for anyone underage or pregnant, which is wise given the lack of data. For healthy adults, consuming glycine as part of whole foods seems safe, but taking big swings with pills or powders introduces uncertainty.

Smart Steps and Solutions

Anyone thinking about glycine supplements should start small—there’s no reason to rush. Checking with a healthcare professional offers real value, especially if you have ongoing health issues or take daily medicines. The science keeps unfolding. Until there’s more detail, it feels wise to get most nutrients from balanced meals, not powders or pills. If you do try a supplement, stay in touch with how your body responds. Side effects, even mild ones, signal that something’s shifted. Paying attention—then adjusting as needed—keeps things safer than blindly following supplement trends.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Aminoacetic acid |

| Other names |

Aminoethanoic acid Glycocoll Gly Aminoacetic acid Aminoethanoate Glycin |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡlaɪsiːn əˌmiːnoʊəˈsiːtɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Aminoacetic acid |

| Other names |

2-Aminoacetic acid Aminoethanoic acid Glycocoll Gly |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡlaɪsiːn əˌmiːnoʊˈæsɪtɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 56-40-6 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3D model (JSmol)` string for **Glycine (Aminoacetic Acid)**: ``` NH2CH2COOH ``` In terms of a **JSmol**-compatible format like **SMILES** for structure rendering: ``` NCC(=O)O ``` Just the string as requested. |

| Beilstein Reference | 392021 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15428 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1070 |

| ChemSpider | 579 |

| DrugBank | DB00145 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03-2119437554-43-0000 |

| EC Number | EC 205-349-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 6077 |

| KEGG | C00037 |

| MeSH | D005999 |

| PubChem CID | 750 |

| RTECS number | MB7600000 |

| UNII | 6F225YG67D |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2021868 |

| CAS Number | 56-40-6 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/3D;JSmol;C(C(=O)O)N` |

| Beilstein Reference | 392080 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15428 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1049 |

| ChemSpider | 576 |

| DrugBank | DB00145 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03-2119448350-54-0000 |

| EC Number | EC 205-349-7 |

| Gmelin Reference | 63795 |

| KEGG | C00037 |

| MeSH | D006999 |

| PubChem CID | 750 |

| RTECS number | MB7600000 |

| UNII | 6DC9Q167V3 |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID7033065 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C2H5NO2 |

| Molar mass | 75.07 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.607 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -3.21 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.01 mm Hg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.60 (amino), 2.34 (carboxyl) |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb = 4.0 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -14.2·10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.478 |

| Dipole moment | 1.25 D |

| Chemical formula | C2H5NO2 |

| Molar mass | 75.07 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.607 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -3.21 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.01 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.60 (amino), 2.34 (carboxyl) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.08 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -13.2·10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | Refractive index (nD): 1.544 |

| Viscosity | 700 mPa.s (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 1.25 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 96.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -528.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -971.8 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 86.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -528.1 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -971.0 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA04 |

| ATC code | A16AA04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory, skin and eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 370 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 7930 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral, rat: 7930 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | NJZQ86N92V |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg bw |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | Glycine Aminoacetic Acid is not classified as hazardous according to GHS (Globally Harmonized System); no GHS labelling is required. |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry, and well-ventilated place. Avoid breathing dust. Wash thoroughly after handling. Wear appropriate personal protective equipment. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 400 °C (752 °F; 673 K) |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 7930 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (oral, rat): 7930 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | PD0875000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg body weight |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed. |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sarcosine Beta-Alanine Alanine Diketopiperazine (Glycine dimer) Glycylglycine Glycylglycylglycine Iminodiacetic acid |

| Related compounds |

Sarcosine Beta-Alanine Glycylglycine |