Fructose: A Deep Dive into Its Past, Present, and Future

Historical Development

Humans noticed the sweetness in fruits well before chemistry added a name to it. People crushed berries, apples, and grapes, recognizing that something inside gave them their pleasant flavor and a quick energy boost. In 1847, Augustin-Pierre Dubrunfaut, a French chemist, pinpointed fructose as a distinct sugar, separating it from the more familiar cane sugar (sucrose) and grape sugar (glucose). This discovery came at a time when countries searched for new, industrial food sources. Over time, food scientists found ways to extract fructose from different plants, especially corn, and by the late 20th century, technologies advanced to convert glucose from corn starch into high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), reshaping the food and beverage landscape. Food manufacturers found a cost-effective sweetener with versatile properties, and it became a staple in sodas, baked goods, and sweetened dairy products. Without a doubt, fructose has shifted the curve on how societies experience sweetness, access affordable calories, and manage public health challenges.

Product Overview

Fructose appears both as a simple sugar in whole fruits and as a refined ingredient in processed foods. Pure crystalline fructose comes as fine, white granules with a clean, intensely sweet taste—sweeter than sucrose, so a smaller amount reaches the desired flavor. The food industry values fructose for its ready solubility and resistance to crystallizing in refrigerated environments, which proves useful for soft drinks and cold desserts. High-fructose corn syrup, a mixture of fructose and glucose, became widespread in the global market given its low price compared to cane sugar and its technical properties. Today, fructose stands among the most consumed sweeteners, driven partly by the expansion of processed food and beverage businesses but also by changing consumer habits seeking convenience and flavor.

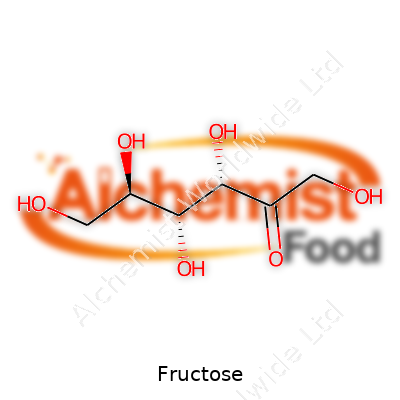

Physical & Chemical Properties

A closer look at fructose reveals a sugar with a unique molecular structure. It has the formula C6H12O6, the same as glucose, but arranged differently, making it an isomer. In crystalline form, fructose tastes about 1.2 to 1.8 times sweeter than sucrose, depending on temperature and concentration. It melts at around 103 °C, easily dissolves in water, and draws moisture from the air. This hygroscopic property helps keep baked goods moist but can make storage tricky in humid climates. Chemically, fructose belongs to the ketose sugar group, containing a ketone functional group rather than the aldehyde group in glucose. This affects its reaction patterns in food processing and its pathways in the human body. Its sweetness increases at lower temperatures, which gives frozen treats a smoother, more pleasing sensation on the palate.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Food safety authorities like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) have laid out clear standards on fructose purity and use. Refined crystalline fructose intended for direct consumption or food manufacturing usually boasts a purity level above 98%, with strict limits on moisture, insoluble materials, and microbial contamination. Labels must declare fructose as an ingredient, either singly or as part of blends like high-fructose corn syrup, to inform allergy sufferers and help customers control their sugar intake. Recent years brought a wave of consumer scrutiny to food labeling, so some producers highlight the natural origin of fructose in fruit-based foods or clarify the percentage of fructose in mixed sweeteners. Regulations change from region to region, which sometimes leads to confusion when comparing international products but pushes companies toward clearer, more transparent labels.

Preparation Method

Extracting fructose starts with plant sources rich in sucrose or starch. The traditional route involves processing corn starch by breaking it down into glucose using enzymes, then converting a portion to fructose using glucose isomerase. This is the key step that sets high-fructose corn syrup apart from standard glucose syrup. For crystalline fructose, some producers draw from inulin-rich plants like chicory, hydrolyzing inulin to produce free fructose, which is then purified and crystallized. The process includes steps for decolorization, filtration, and evaporation to ensure a high-purity end product. Throughout, each batch undergoes rigorous testing for contaminants, as required by food safety laws. The efficiency of the industrial method means vast output at relatively low cost, feeding the demands of a global food system.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In chemical terms, fructose proves flexible in the hands of food chemists. It readily participates in the Maillard reaction, which is a cornerstone of baking, roasting, and flavor development. Compared with glucose or sucrose, fructose produces browning faster at lower temperatures, giving baked goods a more pronounced color and aroma. Fructose can undergo dehydration reactions, forming compounds like hydroxymethylfurfural under heat—a marker in honey adulteration tests and a topic in discussions about food safety. Modification of fructose forms the basis for some bio-based polymer research, seeking alternatives to petroleum-derived plastics. Its reactive ketone center also opens doors to new food ingredients and flavors through controlled chemical reactions, such as creating fructooligosaccharides, which promise potential as low-calorie fibers with prebiotic benefits.

Synonyms & Product Names

Science and commerce have given fructose a long list of aliases. Chemists refer to it as fruit sugar, levulose, or D-fructose. Supermarket shelves display it as crystalline fructose, high-fructose corn syrup (with varying ratios like HFCS-42, HFCS-55), and in blends described as glucose-fructose or isoglucose, especially in Europe. Sometimes, ingredient panels simply list "fructose," which can confuse consumers trying to differentiate between naturally occurring fruit sugars and those added during processing. Although fructose naturally occurs in apples, pears, watermelons, and honey, the bulk of added fructose comes from industrial-scale production. Clear labeling and public education help bridge this gap, enabling more informed choices and building trust between the food industry and the public.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling fructose in large-scale settings requires quality control at every stage. Facilities rely on Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) plans to keep microbial risks low and manage physical and chemical hazards. Crystalline fructose should be stored dry, away from strong odors, since its hygroscopic nature draws in water and foreign aromas. Equipment operators must monitor temperature closely because overheating triggers unwanted caramelization or decomposition, ruining flavor and color. Regulatory bodies periodically audit both processes and products for compliance, especially given concerns over foodborne illnesses and allergen management. These standards aim to protect workers, maintain consistent product quality, and ensure that food-grade fructose meets the expectations set by law and by the people who rely on it for taste, texture, and nutrition.

Application Area

Fructose has carved out a space in many industries. Food manufacturers favor it for drinks, yogurts, jams, and snack bars because it dissolves quickly and provides sweetness even at lower concentrations. Its intense flavor profile means manufacturers can use less by weight, cutting down total caloric load or balancing taste in reduced-sugar foods. Bakers turn to fructose to boost browning and retain moisture in pastries, while ice cream makers tap its ability to stay liquid at low temperatures, keeping frozen treats scoopable. Some pharmaceutical products incorporate fructose for taste-masking and improved patient compliance. Its dehydrating ability also lets food scientists fine-tune product texture. Despite these advantages, the link between high intake of added fructose and rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver disease has sparked debate, fueling research, reforms in product formulation, and shifts in national dietary guidelines.

Research & Development

The last decades brought a flurry of research on fructose. Scientists assess its role in metabolic diseases, trying to separate the impact of pure fructose, fructose from whole fruit, and mixtures like HFCS. Public health groups and academics debate how the body handles fructose differently than glucose, focusing on the liver’s unique pathway for converting fructose to fat. On the technical side, food scientists experiment with low-glycemic-index sweeteners, blending fructose with fibers or polyols to reduce the blood sugar spike. Agronomists investigate crop varieties and enzyme technologies to lower costs and increase sustainability. The drive for more natural, less processed ingredients also shapes R&D, as consumers demand cleaner labels and plant-based foods. This wave of curiosity and skepticism challenges longstanding assumptions while pushing companies to develop new products and healthier choices.

Toxicity Research

A growing body of research highlights the health concerns tied to high fructose consumption, mostly through sweetened drinks and processed food. Studies document how excessive fructose intake can overwhelm the liver, leading to fatty liver disease, higher triglycerides, and increased risk for insulin resistance and obesity. Animal models and long-term human studies reveal that fructose contributes to metabolic disruption differently from other sugars, in part because it bypasses key checkpoints in glucose metabolism. Experts warn against demonizing fruit, since the fiber and micronutrients in whole foods slow sugar absorption and bring health benefits. Still, global health agencies urge people to limit added sugars, especially high-fructose syrups, and call for clearer product labelling and stronger policy interventions. Ongoing toxicity studies probe not just acute effects, but also the subtle, chronic changes that occur in real-world diets, where multiple sources of sugar frequently combine.

Future Prospects

Demand for sweetness spans continents, but the road ahead for fructose looks increasingly complex. As more consumers draw lines between added and intrinsic sugars, whole-food sources like fruit and honey gather favor over processed offerings. Sustainability joins health as a concern, spurring investments in greener production methods and crop improvements. Food technologists race to balance palatability, shelf life, and nutritional value, experimenting with sugar alternatives, novel fiber blends, and new sweetener formulations. Policymakers respond to shifting science and public pressure, weighing health taxes, advertising restrictions, and reformulation incentives. For those working in food development or nutrition, the future of fructose means constant vigilance—embracing transparency, tracking evolving guidelines, and supporting research that cares for both taste and long-term well-being.

What is fructose and how is it different from other sugars?

The Basics Behind Fructose

Fructose pops up every time someone grabs an apple, sips juice, or opens a soda can. Found naturally in fruit, honey, and some vegetables, fructose earns its title as the “fruit sugar.” The science tells us that fructose is a simple sugar, or monosaccharide, just like glucose and galactose. Still, it doesn’t behave like those other sugars inside the body.

Fructose Versus Other Sugars

Most of us picture sugar and think of the white crystals in kitchen jars—table sugar, or sucrose. Sucrose is half glucose, half fructose. Glucose gets a lot of attention because it’s the main energy player in our blood and fuels cells fast. The body can take in glucose and either send it straight to the bloodstream or store it for later.

Fructose follows a different set of rules. Unlike glucose, which almost every cell loves to use, fructose heads to the liver for processing. The liver converts fructose into glucose or stores parts of it as fat. That’s where stories about fructose and health headlines often begin.

Spotlight on Health and Diet

As someone who likes to check ingredient lists, it’s tough not to notice the rise of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in so many packaged foods and drinks. HFCS blends glucose and fructose, but often tips the balance toward more fructose than you’d find in cane sugar. Studies from places like the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition link large amounts of added fructose with higher risks for obesity, fatty liver disease, and even heart trouble. Fructose sneaks into sweetened drinks, sauces, and even bread.

On the other hand, eating whole fruits offers a very different story. Fruit delivers fructose alongside fiber, vitamins, and a lot of water. These extras slow the absorption of sugar and keep the body in balance. Real fruit doesn’t flood your system like a bottle of soda would. Even research funded by the World Health Organization points out that fruit rarely causes the same metabolic problems as sweetened drinks or snacks packed with added sugar.

The Importance of Choosing Wisely

Grocery stores tempt shoppers with processed options everywhere. Reading labels helps cut back on unnecessary fructose. Swapping out sweetened sodas for sparkling water or snacking on nuts instead of candy goes a long way. Talking with a registered dietitian adds another layer of support, especially for those who want to watch their sugar intake.

Families can set healthier patterns by keeping whole fruits on the table and saving desserts for special occasions. Cooking more meals at home makes it easier to control what goes in the pot. For people with diabetes or high blood pressure, small switches—from white bread to whole grains, or from processed snacks to carrots and apples—make meals not only safer but tastier.

What Comes Next

There’s real power in understanding how different sugars move through the body. Schools can teach these facts early, so kids learn to see past bright wrappers and clever ads. Doctors, nutritionists, and community groups all have a chance to push back on the steady stream of sweetened drinks that lead to long-term disease. By paying attention to what sits on the plate—and what floats in a glass—everyone can make choices that support energy and health for the long run.

Is fructose safe for people with diabetes?

Understanding Fructose

Fructose is a simple sugar found in many fruits, honey, and processed foods. It shows up on nutrition labels, sometimes hiding behind terms like “high fructose corn syrup.” For someone living with diabetes, keeping blood sugar balanced isn't just a daily goal—it's a constant part of life. Grocery shelves make health claims about all sorts of sweeteners, but is fructose really a friend to those who watch their blood sugar?

How Fructose Affects Blood Sugar

Unlike glucose, fructose doesn’t raise blood sugar levels right away. The liver takes care of fructose before it heads elsewhere in the body, turning much of it into glucose. A few studies show that, in small amounts, fructose doesn't spike blood sugar as fast as table sugar does. This fact led some to call fructose a “safer” sweetener for diabetes. What’s important to know is that too much fructose can overload the liver. Over time, this can cause issues such as increased fat buildup, which connects to insulin resistance. Insulin resistance means the body gets less effective at moving sugar out of the blood, which raises long-term risks for people with diabetes.

Natural vs. Processed Sources

Eating a handful of blueberries in late summer feels very different than chugging a bottle of soda with high fructose corn syrup. Fruit comes packed with fiber, water, and a host of vitamins. Fiber lessens blood sugar jumps. Soda, on the other hand, drops a big hit of fructose straight into the system. Several nutritionists and diabetes experts recommend sticking with natural sources of sweetness. Large research studies, such as the one published in the journal Diabetes Care, show that people managing diabetes best often eat more fruits and fewer processed foods. Fruit, eaten whole, rarely contributes to runaway blood glucose because of its fiber and nutrient content.

Long-Term Risks of Too Much Fructose

Doctors at the Mayo Clinic warn that constant high intake of fructose—especially from sweetened drinks and desserts—drives up triglyceride levels. High triglycerides come with a higher chance of heart disease, which already gives people with diabetes enough to worry about. Studies from the American Diabetes Association link heavy fructose use to higher rates of gout, fatty liver disease, and metabolic syndrome.

Better Options for Sweetness

It’s tough to give up sweets altogether. Overnight changes rarely stick. For people with diabetes, making small shifts—choosing fruit over syrup, adding cinnamon instead of sugar—can lower health risks. Registered dietitians guide patients to drop sweetened drinks and explore natural sweetness from berries or apples. Even adding less sugar to coffee each morning helps.

What Works Day to Day

I grew up with a family member who carried a glucose meter everywhere. The numbers on that small screen told the truth faster than any label on a cereal box. Any “safer” sweetener gets tested in real life. Fructose, from a ripe peach once in a while, helped him feel satisfied without spiraling blood sugar. Large servings of fruit juice? They only made management harder. Building a plate with plenty of vegetables and whole fruits—and reserving processed sweeteners for rare treats—made a difference.

Trust in Real Food, Not Labels

Doctors, researchers, and families living with diabetes have learned the same lesson over and over. Labels make big promises, but the body responds best to small, slow changes. Fructose from whole fruit brings benefits, but processed sugars change the game. Food isn’t just about numbers or ingredients. It’s about long-term habits, trust in simple foods, and steady steps toward better blood sugar control.

What are the health effects of consuming fructose?

Understanding Fructose

Fructose lands in the spotlight every time folks talk about sugar. Found naturally in fruits, honey, and some vegetables, it often sneaks into everyday foods as a part of high-fructose corn syrup. Grocery aisles overflow with sweetened beverages, breakfast cereals, snack bars, and sauces—all loaded with this simple sugar. Most people grab these without a second thought, but the story doesn’t end with a sweet taste.

The Story Behind Fructose Research

Digging into studies, a strong link shows up between high intake of fructose and health problems like obesity, fatty liver, and insulin resistance. Researchers at the University of California, Davis, showed that drinking fructose-sweetened drinks can raise liver fat and cholesterol levels in a short timeframe, which doesn’t bode well for heart health. Their work joins a larger pile of evidence suggesting that lots of fructose can change the way your body stores fat and handles blood sugar.

Many experts compare fructose-heavy foods to empty calories. Fruits come packed with fiber, vitamins, and water—holding the sweet stuff in check. Processed foods lose all that. Without fiber slowing things down, sugar rushes straight into the liver. The liver gets overwhelmed, turning fructose into fat, some of which ends up floating in the blood. Over time, this pattern paves the way for metabolic and cardiovascular troubles.

Fructose and Everyday Choices

People often underestimate how easy it gets to overconsume sugar. A glass of soda or a bottle of sweet tea carries far more fructose than a few pieces of fruit. Someone working long hours, picking up fast food or sipping energy drinks to power through the day, sees these hidden sugars pile up without much thought. It’s not just about hunger—it’s about routine, marketing, and quick pleasure.

Much of the issue boils down to the shift from home-cooked meals to processed convenience. Walk into any office, and vending machines glow with choices. Products loaded with high-fructose corn syrup cost less and taste addictive, so companies push them at every turn. Access to healthy options becomes more limited for families with tight budgets.

Hard Facts from the Clinic

I’ve spoken with doctors who’ve seen more kids developing fatty liver disease—once a rare sight outside alcohol abuse. Pediatricians say sugary drinks play a big role. Just a few servings a week can crank up health risks since young bodies process sugar differently. Adults face their own battles, with rates of diabetes and obesity breaking records each year.

Finding a Way Forward

Change rarely happens overnight. Simple swaps like drinking water or unsweetened tea instead of soda make a difference. Reading ingredient lists before tossing things into the cart pays off too. In households that focus more on cooking with whole foods, health problems drop off. Community programs spreading real nutrition info and fighting for better school lunches bring hope for bigger shifts.

Everyone deserves to understand what goes into snacks and drinks. Talking honestly about risks and giving people real choices—with the support of policy—could help communities walk away from sugar overload. Cutting back on added sugars, especially fructose-heavy ones, gets easier with practice. Not every meal has to be perfect, but aiming for fewer processed sweets always pays off.

Is fructose natural or artificial?

What Fructose Means in Everyday Life

Fructose shows up every time someone bites into an apple or peels a banana. This simple sugar comes packed in a lot of fruits and even sits in some vegetables. For years, people picked fruit off trees or pulled carrots from dirt, never worrying about chemistry or labels. Fructose wasn’t a trend, it just stood as part of food straight from the ground.

Now, things look different in grocery stores. Shelf after shelf of packaged foods, sodas, and cereals line up ingredients lists that make people pause. “High-fructose corn syrup” shows up everywhere, raising questions and stirring arguments. Some say all fructose gets lumped together, natural or man-made. It’s hard to blame anyone who feels confused.

The Science Behind Fructose

Fruit carries fructose naturally along with fiber, vitamins, and water. The body digests and absorbs that mix pretty slowly, which is more gentle for blood sugar. Eating an orange means getting some fructose, but not just because juice or concentrated syrup pumps it up. Real fruit provides other nutrients that work alongside sugar in helpful ways.

Factories also pull fructose out of corn and turn it into liquid sweeteners. These processed forms—like high-fructose corn syrup—get slipped into sodas, candies, and even ketchup. This version starts with corn starch, gets broken down by enzymes, and ends up sweeter than regular table sugar.

Why All Fructose Isn't Created Equal

It’s not fair to treat a strawberry like a candy bar just because both deliver fructose. Eating whole fruit hasn’t been shown to cause the same health problems tied to sugary drinks and snacks. Research links high intake of added fructose—mainly from processed food—to more risk for obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver disease. The trouble grows when people regularly drink sweetened beverages or eat a lot of packaged foods with these added sugars.

Fresh fruit, with its water and fiber, helps fill you up before things get out of hand. Most folks could eat several apples or a cup of berries and still not reach the sugar punch of a large soda. More and more studies show that fruit supports heart and gut health, not just because of vitamins, but because of how the body handles these natural sugars.

Sorting Out the Confusion

It matters how fructose gets to your plate. Natural doesn’t mean immune from problems, but fruit eaten whole rarely equals the health burdens researchers tie to processed foods. It’s important to look at how much added sugar comes in every day. Guidelines from top health groups like the American Heart Association suggest keeping added sugars under control—no more than 24 grams a day for most women, 36 grams for most men. That target usually gets blown past because of sodas, not because someone ate an orange with lunch.

Reading labels and choosing foods with fewer processed sweeteners grows more important each year. Real fruit, plain yogurt, homemade snacks—they all give natural sweetness without a science degree or hidden additives. Farmers’ markets and produce aisles offer options that don’t leave people guessing about what’s in their food. Some communities team up with schools, markets, or community gardens to get better access to whole foods, which makes a big difference when budgets feel tight.

The debate around fructose ends up less about the molecule itself and more about where it comes from and what comes along for the ride. Experience shows that paying attention to both the ingredient list and the bigger food picture makes a real difference for health, energy, and even eating enjoyment.

How should fructose be used in cooking or baking?

Understanding Fructose’s Role

Fructose shows up in kitchens as a natural sweetener, usually drawn from fruits and sometimes corn. Folks have grown curious about how it stands apart from the usual white sugar everyone sprinkles over recipes. Fructose tastes sweeter than table sugar, so those hunting for lower-sugar recipes sometimes go for it, hoping to keep sweetness but cut down on the amount poured in.

Why People Reach for Fructose

In baking, one attraction comes from how fructose dissolves fast and brings a more pronounced sweetness. Some home bakers find their cookies brown just a bit more quickly with it, since fructose caramelizes at a lower temperature than sucrose. I’ve swapped in a bit of fruit-derived fructose before—particularly in muffins and soft cakes hoping for a chewier crumb—but learned early to watch the oven closely since they go golden before a timer rings.

What draws some to fructose also sits in its effect on texture. Soft, chewy cookies and moist cakes often become easier with fructose on the ingredient list. That lighter, more tender bite can matter for folks with dentures or small kids missing a molar or two. Jams and jellies sometimes benefit from the way fructose draws water, helping retain a spreadable texture without reaching for artificial stabilizers.

The Flip Side: Health and Cooking Pitfalls

Authors and nutrition experts often flag concerns about fructose, especially in large amounts. Unlike glucose, which every cell in the body soaks up, fructose mostly lands in the liver. Studies suggest too much of it may lead to fatty liver in the long run, especially when poured in from sodas or processed food. A diet heavy with fructose sometimes links with higher triglycerides, which doesn’t do anyone's heart any favors.

Baking with fructose at home rarely reaches those worrisome levels, but balance remains key. Kids tend to love extra sweet baked goods, but cutting total sweetness with spices or zests, and stretching out the fruit instead of just loading up on sugar, brings more flavor and less risk. Those living with diabetes or prediabetes often ask about fructose, since it raises blood sugar slower than glucose. The glycemic index sits lower, but that shouldn’t open the way to eating endless cupcakes. Observation and moderation almost always win.

Making the Most of Fructose in Everyday Recipes

In my kitchen, I only swap out regular sugar for fructose in specific recipes, not across the board. Shortbread, which depends on sugar’s coarser texture, just doesn’t behave the same way with fructose. On the other hand, brownies, fruit bars, or oatmeal cookies keep their chew well with a measured dose. For those going that route, reduce the overall amount, usually to about two-thirds of the sugar called for, since fructose packs more punch.

Every recipe deserves testing and tinkering when making big changes. Too much fructose weighs down airy cakes, sometimes making them dense or too sticky. Sourdough and regular yeasted breads don’t like big shifts in sugar types, which can slow down or even stall fermentation. For salad dressings or marinades, a dash of fructose from mashed berries or honey helps balance acids without tipping the scales on sweetness.

Experimenting helps, but it pays to keep tabs on the bigger picture—using fructose for its strengths while remembering less is often more. Taste matters, and so does health. Trying new things helps keep both in focus.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2R,3R,4S,5R)-2,5,6-trihydroxyhexanal |

| Other names |

D-arabinulose D-fructosio Fruit sugar Levulose |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfruːk.toʊs/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (2R,3S,4S,5R)-2,5-dihydroxyhexanal |

| Other names |

D-arabinulose D-fructose fruit sugar levulose |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfruːk.toʊs/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 57-48-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1724224 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15824 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL95164 |

| ChemSpider | 5838 |

| DrugBank | DB01082 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.038.252 |

| EC Number | EC 3.2.1.26 |

| Gmelin Reference | 79046 |

| KEGG | C00095 |

| MeSH | D005367 |

| PubChem CID | 5984 |

| RTECS number | LR2975000 |

| UNII | 3OWL53L36A |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CAS Number | 57-48-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1724221 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:15824 |

| ChEMBL | CHEBI:28757 |

| ChemSpider | 5054 |

| DrugBank | DB01842 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.058.884 |

| EC Number | EC 3.2.1.26 |

| Gmelin Reference | 58947 |

| KEGG | C00095 |

| MeSH | D005367 |

| PubChem CID | 5984 |

| RTECS number | LU5425000 |

| UNII | ILY9D9U6JD |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4020867 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H12O6 |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g/mol |

| Appearance | Colorless crystals or white powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.59 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 79 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.57 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.01 hPa (20°C)> |

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.52 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.10 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Dia-0.000009 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.481 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 1.94 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H12O6 |

| Molar mass | 180.16 g/mol |

| Appearance | White, odorless, crystalline solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.59 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 790 g/L (25 °C) |

| log P | -2.57 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.01 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 12.1 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 1.76 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.474 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 3.52 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 219.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1265 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2818 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 210.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1265 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | –2811 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A11CC04 |

| ATC code | A11CC04 |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 410 °C (770 °F) |

| Explosive limits | Explosive limits: 42-68 g/m3 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 15,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 15000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WN6500000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 g |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Main hazards | May form explosive dust-air mixtures. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | No hazard statements. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0-N |

| Autoignition temperature | 410 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (rat, oral): 15,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 15000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | K630 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 g |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Arabinose Glucose Mannose Psychose Sorbose Tagatose |

| Related compounds |

Glucose Galactose Sucrose Sorbitol Mannose |