Ferrous Sulfate: From Ancient Uses to Modern Innovation

Historical Development

Long before bottles of iron supplements lined pharmacy shelves or city engineers spread anticorrosion agents across water systems, people noticed the curious properties of a mineral that looked strikingly green when exposed to air. The ancient Greeks and Romans sourced “green vitriol”—a mineral form of iron sulfate—to use as a pigment. In the Middle Ages, artisans used ferrous sulfate to make deep black ink for writing manuscripts. Alchemists mixed it into potions, searching for ways to turn base metals into gold or treat mysterious illnesses. During the Industrial Revolution, ferrous sulfate shifted from curiosities and mystic remedies into an industrial raw material, useful in manufacturing dyes, treating fabrics, and making iron compounds for fertilizer. Its unmistakable tang and color always left a mark.

Product Overview

Most folks know ferrous sulfate as a supplement to help with iron deficiency anemia. But the reach stretches far wider. The product exists both as the familiar blue-green crystals—often called "copperas"—and as a dry, powdery form made for agriculture or industry. It enters water treatment plants as a coagulant, lands in commercial agriculture to supplement soil, and fits into the pharmaceutical sector for therapies treating iron-deficient blood. Each use sees a tweak in form, purity, or granulation, depending on what’s needed.

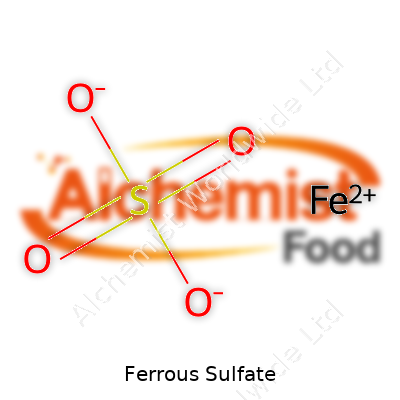

Physical & Chemical Properties

Ferrous sulfate shows up most often as heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O), a green-blue crystal that dissolves well in water. In dry air, these crystals lose water and turn white. In storage bins, they clump and harden if air gets in. This salt reacts easily with oxygen—leaving it exposed turns it rusty and brown. It melts when heated above 64°C and breaks down to a powder as water evaporates. In chemistry labs, its reactivity as a reducing agent stands out, letting it drop electrons and foster reactions. These physical shifts, from color to state, signal its readiness for industrial transformation and practical use.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers list at least 20% iron content when they sell technical or feed-grade ferrous sulfate. Pharmaceutical-grade runs even higher and requires tests for heavy metals, microbial contamination, and organic impurities. Each bag, drum, or ton-sized super sack arrives tagged with the name, grade, batch number, iron percentage, net weight, and safety information based on hazard guidelines. Labels warn about its ability to stain and the need to avoid inhalation or ingestion without medical approval. Precise tracking supports everything from healing hospital patients to feeding cattle or treating billions of liters of municipal water.

Preparation Method

Large-scale producers extract ferrous sulfate by dissolving iron ore in sulfuric acid, sometimes using steel byproducts straight from factories. This picks up both speed and cost efficiency. Some operations recover iron sulfate as a byproduct while making titanium dioxide or from cleaning steel surfaces with acid, where wastewater streams yield dissolved iron salts. Filtering and cooling concentrate the product, which is then crystallized, dried, and milled. The method depends on what’s available—natural ore or leftover steel still loaded with iron. Quality hinges on purification during these steps, especially when the end use demands pharmaceutical or food-grade.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Mixing ferrous sulfate with oxidizing agents—like hydrogen peroxide—turns it into ferric sulfate, a useful water treatment chemical with stronger coagulating power. Adding alkalis like sodium hydroxide produces iron hydroxides, often used for contaminant removal or coloring pigments. In fertilizer blending, combining ferrous sulfate with potassium compounds provides plant-available nutrients for fast iron uptake. Chemistry students rely on it for dose-response experiments, and manufacturers tweak particle size or hydration level for stubborn mixing problems or slow-release applications. These reactions shape how the salt solves practical problems—from coloring inks to cleaning groundwater.

Synonyms & Product Names

Ask around the lab or factory floor and someone will call ferrous sulfate “copperas.” Others know it as “iron(II) sulfate,” “green vitriol,” or “sal de Inglaterra.” Bulk suppliers use terms like FESO4, iron sulfate, or simply “feed-grade iron.” Pharmaceutical bottles list it as “ferrous sulfate heptahydrate” on ingredient labels. These different tags matter when tracking shipments, reading safety sheets, or sorting through patents and research. No matter the name, experienced buyers know to look for color, hydration, purity, and grain size to suit each task.

Safety & Operational Standards

Ferrous sulfate does the most good and least harm when handled safely. Inhaled dust irritates the nose and throat, and accidental swallowing without guidance can poison adults or children. Business standards set storage and handling rules: keep in sealed containers, avoid moisture, use masks and gloves, and wash spills with plenty of water. In workplaces, regulatory agencies lay out limits for airborne dust and call for regular training. In pharmaceuticals, strict batch testing and documentation follow current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMP). On the farm, proper blending keeps iron levels safe for livestock and crops. Health concerns tied to accidental overdose—nausea and sometimes worse—make strict measures not just a legal box to check, but a basic work habit.

Application Area

Doctors prescribe ferrous sulfate for anemia nearly everywhere, given iron’s vital place in making hemoglobin. In water treatment plants, operators dose it to settle out clay and phosphates, clarifying drinking water or treating waste. Farmers and golf course managers spread it to green turf and correct yellowed leaves where iron comes up short in soil. Manufacturers use it to dye textiles, treat leather, and make magnetic inks for printing. Developers recycle it through environmental cleanup projects—removing arsenic or chromium from groundwater or soil. Across these spaces, the common thread is practical chemistry—iron on the move from a simple salt to thousands of products and solutions.

Research & Development

Teams in universities dig into how ferrous sulfate interacts with the human gut microbiome, looking to reduce the stomach discomfort many patients report. Agricultural scientists test it for new soil blends that fight crop disease and foster sustainable yield increases. Engineers research modified iron salts for faster, more complete water purification. In each case, questions about bioavailability, absorption, and environmental impact drive fresh trials and patent filings. I’ve seen public-private partnerships funnel funds into these efforts, blending academic rigor and market needs. Peer-reviewed papers fuel progress, but practical breakthroughs happen when someone finds a way to solve an old problem with an adjusted form or delivery method.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists have mapped the dangers of ferrous sulfate for decades. A dose only a little higher than the daily medicinal tally can tip over into poisoning—early symptoms stem from damage to stomach and bowel before iron piles up in vital organs, sometimes with fatal results, especially in children who get hold of pills. Animal trials and patient reports have shaped safety warnings and highlighted the need for child-resistant packaging. Environmental studies measure runoff from fields and treatment plants, tracking possible harm to aquatic life. Modern research pushes for safer formulations, controlled-release tablets, and better overdose treatment protocols that save lives by neutralizing free iron before it causes lasting harm.

Future Prospects

Ferrous sulfate stands at another pivot point as industries seek cleaner water, higher-yield crops, and greener tech. Researchers carry hope into making low-cost iron supplements with less stomach side effects, while environmental projects look to use ferrous sulfate to lock up toxic heavy metals in soil and water. Startup companies seek smarter blending techniques for fertilizers to target iron deficiencies without waste or runoff. Water engineers test new dosing systems that cut chemical use by improving solubility or mixing—driven by both tighter regulation and budget constraints. Future gains hinge on resolving old trade-offs: boosting plant absorption, reducing patient side effects, and making each kilogram serve a broader range of public needs. In my years following product pipelines, I’ve learned that the best advances come when real-world experience meets fresh data and a willingness to rethink how a basic chemical can fuel smarter, safer progress.

What is ferrous sulfate used for?

What Ferrous Sulfate Does in Health

Ferrous sulfate pops up on pharmacy shelves, but its job doesn’t end with a bottle of iron pills. Doctors reach for it often, especially for patients with low hemoglobin. That’s anemia. I’ve watched patients drag themselves into clinics, exhausted from iron deficiency. Their energy picks up after they start on ferrous sulfate. Iron works as a building block for hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that moves oxygen around the body. A lack of iron leaves people foggy, weak, or even short of breath from walking across the room. Ferrous sulfate changes that, giving people a simple way to refill their iron stores.

Doctors recommend this compound because the body absorbs this form of iron better than many others. The World Health Organization lists it as an essential medicine. Pregnant women especially need more iron; their blood volume surges, which dilutes existing stores. In clinics, I’ve seen iron deficiency climb when money gets tight—iron-rich foods like red meat or leafy greens become less common on dinner tables. For some, a daily pill makes all the difference.

Ferrous Sulfate in Agriculture and Industry

Fertilizer doesn’t just grow from dirt and water. Plants depend on trace minerals, and ferrous sulfate offers a handy tool for farmers trying to deal with sickly, yellowing crops. Fields short on iron show it in the leaves: they lose their green, and growth stalls. By sprinkling or dissolving ferrous sulfate, farmers lift productivity and keep crops looking healthy. Roses, lawns, and even golf courses often get a dose of this compound.

Stroll past an old wooden fence or car, and you’ll notice the reddish-brown tint from rust. In industry, ferrous sulfate plays a part in wastewater treatment. Factories use it to help clean up heavy metals and other pollutants before water runs back into rivers or lakes. The compound acts like a sponge, helping neutralize toxins and making filtration easier. Good water quality matters not just to the industry, but to the people living nearby.

Concerns and Everyday Use

No medicine or compound carries zero risk. Some people taking these supplements face stomach upset or constipation. Too much iron poses real hazards, especially for children. Hospitals see cases of iron poisoning every year—so keeping bottles out of reach remains crucial. Anyone trying the supplement should talk to a doctor first, not guess based on fatigue alone. Blood work tells the full story.

Misuse in gardening can hurt too. Pouring on more ferrous sulfate than needed will not turn a yellow lawn green overnight. Over time, it can harm soil and run off into streams. Sustainable use depends on soil testing and local guidelines rather than quick fixes. Communities can benefit most when industry, medicine, and agriculture keep the wider environment in mind.

Better Awareness, Better Solutions

Iron deficiency remains the world’s most widespread nutritional disorder. Busy clinics see it daily. But ferrous sulfate makes a difference, whether in pills or plowed into soil. More public education can curb risky self-medication and overdosing, while simple soil checks guide gardeners and farmers to use just what’s needed. These steps can help stretch budgets and protect health, whether you care for your family’s diet, your backyard tomatoes, or a field of wheat.

Ferrous sulfate works as a simple, sometimes overlooked tool—when used with care, it can brighten lives and landscapes alike.

What are the common side effects of ferrous sulfate?

Iron Pills That Bring Trouble

Ferrous sulfate has a clear job: boost iron in people whose levels are too low. I’ve noticed it gets handed out a lot in clinics, especially to folks with anemia. Doctors trust it because it works, but almost anyone who’s taken it knows there’s a price to pay. These pills can make daily routines a little rough.

Stomach Upsets and How They Show Up

The most obvious issue tends to be in the gut. My patients usually mention nausea before anything else. This feeling lingers even hours after the pill. Some folks tell me iron leaves them with sharp stomach cramps that don’t let up until the body clears enough iron out. There's a reason a lot of people dread their next dose.

Diarrhea and constipation both show up, sometimes in the same person depending on their day and what they’ve eaten. In plenty of cases, patients see their stool turn dark or even black. That can scare someone who doesn’t expect it. It isn’t blood most of the time—just the iron talking.

Metallic Taste and Heartburn

Iron tablets bring a metallic taste that sticks around after swallowing. Water doesn’t get rid of it. For some, this strange taste makes every meal less enjoyable. Pills also irritate the lining of the esophagus and stomach. Heartburn or acid reflux aren’t rare. Those burning sensations push people to skip doses now and then.

Less Talked About—But Just as Real

There are headaches that refuse to budge, even with rest. Sometimes, people report feeling dizzy or having a sense of fullness that follows them all day. A few break out in hives or notice rashes. Allergic reactions don’t hit everyone, but they can be severe and need quick attention.

Who Feels These Effects More?

Iron supplements seem harsher on older adults and anyone with a sensitive stomach. Folks with a past of stomach ulcers or digestive issues often have the hardest time. Taking other medications, especially ones that already upset the stomach, just adds to the trouble. It makes sense to check with a doctor before diving in, to see if another iron form causes fewer problems.

Making the Daily Dose a Little Easier

There are ways to dodge some of the pain points. I often suggest taking ferrous sulfate with a bit of food to cushion the blow, though this can cut how much iron you absorb. Splitting the daily dose into smaller amounts through the day helps some people keep symptoms lower. Drinking plenty of water gets things moving in the gut and helps with constipation.

For those who just can’t cope, switching to a gentler iron, like ferrous gluconate, sometimes does the trick. Liquid forms, too, can be easier on the body, but they can stain teeth if you aren’t careful. Always running these changes by a health professional keeps things safer.

Why Paying Attention Matters

Iron is essential, but no one sticks to a supplement that keeps them feeling lousy. Ignoring side effects means people quit early, leaving their anemia untreated. It helps to listen to your body, talk about every side effect, and try out adjustments until something works. Staying healthy takes effort, but nobody should suffer in silence just to see their numbers climb.

How should I take ferrous sulfate for best absorption?

Understanding Why Iron Matters

Iron isn’t just a footnote on a blood test. It shapes how we feel every day. Without enough, energy drops, focus skips, and the body loses its usual spark. Ferrous sulfate has become a common solution for iron deficiency because it works fast and remains affordable.

Bringing Iron to the Table

Taking ferrous sulfate can be a confusing experience if you go into it unprepared. Many folks get handed a prescription and a shrug. Years ago, I made that trip to the pharmacy after a routine check caught low iron. I remember staring at a bottle and wondering if it mattered whether I swallowed it with lunch or waited until bedtime. The pharmacist, thankfully, caught the hesitation and offered the two most important tips I’ve followed since.

Timing and Stomach Matters

Swallowing ferrous sulfate on an empty stomach gives your body the clearest path for absorbing it. Acid in your stomach plays a big role, so if you take it with plain water, about an hour before a meal or two hours after, that usually leads to the best results. Eating right before or after can block some of the iron, especially certain foods. Dairy and eggs, high-fiber bread, coffee, and tea all leave your body reaching for iron it can’t grab.

Of course, life rarely runs like a science experiment. Some people, myself included, feel queasy after iron on an empty stomach. Taking it with a light snack, especially something rich in vitamin C like half an orange or a handful of strawberries, lets the body soak up more of the iron without the queasiness that can sometimes push us to skip doses. Vitamin C plays a real supporting role. Squeeze that extra wedge of lemon into your water—every little bit helps.

Getting Around Hurdles

Medications make a difference here. Calcium pills, antacids, and some antibiotics stop your body from grabbing the iron you just took. Spacing out iron by at least two hours from these can spare a lot of frustration. If you need multiple daily pills, creating a simple schedule—putting reminders in your phone or writing it on a sticky note—reduces mistakes. I started setting an alarm to take my iron before breakfast and then another to remind myself not to dive into coffee afterward. It built a rhythm that stuck after a couple of weeks.

Trying to Stay on Track

Constipation, nausea, and dark stools pop up often for iron users. Drinking more water and including high-fiber foods, such as beans or whole grains, helps the digestive system keep moving. If side effects drag down your commitment, talking to a healthcare professional can uncover other forms of iron that might be easier for you. Slow-release or lower dose options often exist, but checking with an expert ensures you don’t trade one issue for another.

Building Confidence With Trusted Sources

Health choices get easier when you rely on trustworthy, clear advice. Medical resources such as the National Institutes of Health offer detailed, readable guides on iron. If your doctor’s explanations leave you lost, patient organizations like the Iron Disorders Institute often break things down in straightforward language. Bringing these sources to your appointments helps build a clearer plan that works in your daily life.

Putting It All Together

Absorbing iron from ferrous sulfate boils down to the small choices—meal timing, pairing it with vitamin C, and keeping other pills apart. Talking openly with health professionals when symptoms or confusion creep in can keep you on track. The key comes from learning what your own body responds to and not giving up if things feel tricky in the beginning.

Can ferrous sulfate be taken with other medications?

Understanding Ferrous Sulfate’s Role

Ferrous sulfate lands on the prescription pad for people managing low iron. Doctors recommend it for anemia, especially after blood loss or during pregnancy, when the demand for iron shoots up. Iron is no bit player—without it, muscles give out, energy drops, thinking gets foggy. Anyone who has fought with fatigue or headaches after skipping their supplements knows it well.

Mixing Medications Isn’t Always Simple

People juggling several medications often wonder who plays nicely together. Ferrous sulfate throws in some twists. Many over-the-counter and prescription drugs can tangle with it, changing how well the body picks up iron or the other medicine.

I remember a patient who couldn’t shake her tiredness, even after starting iron pills. It turned out she washed down her tablet with her morning calcium supplement. Calcium, found in antacids and dairy, can block the body from grabbing that iron, making both a waste. Magnesium or zinc tablets can mess with absorption, too. Doctors usually say to leave at least two hours between taking iron and these minerals.

Antibiotics like tetracycline and ciprofloxacin face similar trouble. If someone swallows ferrous sulfate and one of these antibiotics together, the iron can hug the antibiotic and stop it from working well. That leads to infections that linger—or come back stronger. Thyroid medicines and some meds for Parkinson’s disease also lose their spark next to iron.

Finding a Way Around Drug Interactions

Managing this dance takes awareness, not just from doctors but from anyone taking these medications. Doctors run through medication lists, but patients need to bring their questions, too. Leave iron and milk or antacids apart by at least two hours. Set reminders or write out a schedule. A simple pillbox or smartphone alarm can help people stick to the gap.

Iron isn’t always gentle on the stomach. Nausea, cramps, or bathroom troubles make people rethink their routine. Taking ferrous sulfate with a small meal (not dairy) can help, but high-fiber foods like bran may drag it down, just as calcium does. Citrus juice boosts iron’s effect, so a little orange or lemon in water goes a long way. In my experience, these adjustments made a difference for folks feeling defeated by their iron prescription.

Talking to Healthcare Teams Matters

Surveys show that over half of adults over 50 pop at least five daily medicines or supplements. With numbers like that, it’s easy for problems to slip through. Pharmacists and doctors need to ask the right questions and share details about possible interactions. Patients who tweak their routines based on these tips often feel stronger within weeks. Understanding how to space out medications keeps both anemia and other health problems under control, without trading one for another.

Smarter Routines, Better Results

Ferrous sulfate offers a powerful fix for low iron but demands a little planning around other pills and foods. Conversations with healthcare professionals open the door to safer, steadier progress. Years of working with patients remind me: the small choices—whether to take pills with breakfast, to read the bottle, to call with a question—shape our results more than any instruction leaflet ever could.

Who should avoid taking ferrous sulfate?

Ferrous Sulfate and Why Doctors Prescribe It

Ferrous sulfate shows up on so many doctor’s prescriptions because it bolsters the body’s iron supply. Many folks rely on it to fend off iron deficiency anemia, which can sap a person’s energy and make every day feel like a slog. The supplement does help, but it’s far from a one-size-fits-all solution. Some people have bodies that can’t handle extra iron, and for these folks, a routine pill poses big risks.

Conditions That Don’t Mix with Extra Iron

People with iron overload disorders, such as hemochromatosis, shouldn’t take ferrous sulfate unless a specialist has thoroughly reviewed their bloodwork and made a rare exception. In hemochromatosis, iron stacks up in the body, slowly building up in places it shouldn’t. Adding more can speed up organ damage, increase risk of liver problems, and bring other trouble. Many people may never know they carry genes for this condition unless they test for it, so asking about family history makes sense before reaching for iron pills.

Children under six can face life-threatening poisoning from ingesting even a handful of ferrous sulfate tablets. It’s easy to overlook how dangerous everyday supplements can be to kids, but iron poisoning moves quickly and damages organs in hours. All iron-containing supplements should stay far out of a child’s reach.

Certain Health Issues Make Iron Supplements Dangerous

People with ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, or other chronic bowel inflammation often see their symptoms worsen with iron. Ferrous sulfate can irritate the lining of the gut, leading to more pain, cramping, or bleeding. If you’re living with one of these conditions, it pays to talk through iron choices with a GI specialist.

Some chronic infections—especially kidney infections or certain bacteria—thrive on iron. Research in the Clinical Microbiology Reviews journal highlights how extra iron can stimulate bad bugs, so doctors in infectious diseases treat iron therapy carefully in those settings.

Prescription Interactions and Special Diets

Supplements like ferrous sulfate can clash with some medications. People on antibiotics such as tetracycline or ciprofloxacin can absorb much less of these medicines if they swallow them with iron. The same goes for thyroid medicines; iron can tie up levothyroxine and leave someone’s thyroid problem uncontrolled. People juggling several prescriptions should run their list by a doctor or pharmacist before starting an iron supplement.

There’s another crew for whom extra iron may do more harm than good: those not actually low on iron. Some people assume fatigue equals deficiency and start taking supplements without any blood tests. The American Family Physician journal spells out that treating non-anemic, well-nourished adults with iron usually yields no benefit and can foster stomach trouble or constipation.

Choosing the Right Course

Getting iron from food rather than pills usually ranks as the safer bet for most. Lean meats, beans, leafy greens—these pack natural forms of iron the body takes in more gently. For anyone worried about deficiency, basic bloodwork (including levels like ferritin and hemoglobin) can give real answers instead of guesses.

Ferrous sulfate fills an important role for many people wrestling with low iron, but the risks run high for those in the wrong health circumstances. Before picking up that bottle at the pharmacy, it’s worth stopping to ask: do I really need this, and do I really know what’s in my blood?

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | iron(2+) sulfate |

| Other names |

Green vitriol Iron(II) sulfate Copperas Melanterite |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈsʌl.feɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | iron(II) sulfate |

| Other names |

Ferrous sulphate Iron(II) sulfate Green vitriol Copperas |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈsʌl.feɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 7720-78-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3588219 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75832 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201474 |

| ChemSpider | 22885 |

| DrugBank | DB01077 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.762 |

| EC Number | 231-753-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | 754 |

| KEGG | C07239 |

| MeSH | D005552 |

| PubChem CID | 24393 |

| RTECS number | NO4565500 |

| UNII | V48V9DWA6X |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 7720-78-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 85363 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75832 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201580 |

| ChemSpider | 22213 |

| DrugBank | DB00653 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.028.774 |

| EC Number | 231-753-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | 878 |

| KEGG | C00539 |

| MeSH | D019375 |

| PubChem CID | 24393 |

| RTECS number | NO4565500 |

| UNII | NCPXPA4O2L |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | FeSO4 |

| Molar mass | 151.91 g/mol |

| Appearance | Greenish or yellow-brown crystalline solid or powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.84 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble |

| log P | -4.0 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 1.99 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 9.5 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | '−46.6×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol' |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.5 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | FeSO4 |

| Molar mass | 151.91 g/mol |

| Appearance | A greenish or yellow-brown crystalline solid or powder |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 2.84 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.1 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~1.99 (for Fe2+ aqua ion) |

| Basicity (pKb) | ~8.79 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | 'Paramagnetic' |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 151 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -824 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 151.0 J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -928.4 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | B03AA07 |

| ATC code | B03AA07 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | **"Warning; Acute toxicity (oral, category 4), Eye irritation (category 2A), Hazard statements: H302, H319; Pictogram: GHS07 (Exclamation mark)"** |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 319 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 319 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WN1400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: 15 mg/m³ (total dust), 5 mg/m³ (respirable fraction) |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 – 60 mg daily |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed; causes skin and eye irritation; may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0- |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 319 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 319 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | WN8400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | 450 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Iron(III) sulfate Iron(II) chloride Iron(III) chloride Magnesium sulfate Copper(II) sulfate Zinc sulfate |

| Related compounds |

Iron(III) sulfate Iron(II) chloride Iron(III) chloride Copper(II) sulfate Zinc sulfate |