Ferrous Lactate: A Deep Dive into Its Journey, Science, and Significance

Historical Development

Long before nutrition panels stamped the side of every food package, scientists and manufacturers searched for better ways to address iron deficiency. In the early to mid-20th century, iron compounds like ferrous sulfate dominated the scene. That came with problems—metallic off-flavors, poor absorption, and gastrointestinal issues. Researchers turned to the idea of chelating iron with organic acids, and lactic acid—already valued in food processing—rose to the occasion. Ferrous lactate emerged around the middle of the century as a solution that promised greater compatibility with food matrices and improved palatability, a leap driven more by need than theory. Since then, its reputation has rested on the work of both lab scientists and nutritionists, who slowly nudged ferrous lactate from an industrial curiosity to a serious contender for food fortification and supplement manufacturing.

Product Overview

Ferrous lactate sits in a unique corner of the ingredient roster as an iron salt formed from lactic acid and iron(II) ions. Manufacturers often source the lactic acid side from fermentation of sugars—a process that keeps the raw material pipeline renewable, an angle food companies appreciate in today’s market. The end result is a fine, pale green powder or granule, easily incorporated into diverse applications like drinks, infant formula, and dietary supplements. What sets ferrous lactate apart, though, is the way this salt sidesteps the notorious flavor and color shifts seen with other iron fortificants. On factory floors, ease of use tends to matter more than elegant chemistry, and ferrous lactate’s solubility and low reactivity often tip decisions.

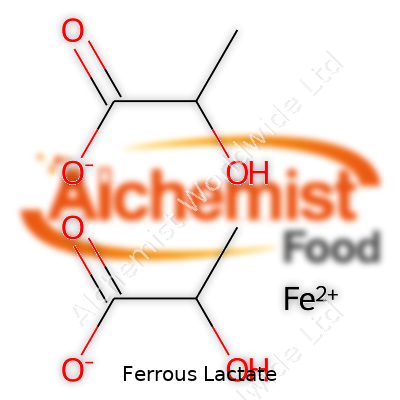

Physical & Chemical Properties

Chemically speaking, ferrous lactate—with the formula C6H10FeO6—contains about 19% iron by mass. Its faint green hue betrays the iron(II) center, known for causing headaches in both labs and kitchens when it oxidizes to iron(III), which produces undesirable yellow-brown tints and off-flavors. At room temperature, ferrous lactate dissolves well in water but not in most organic solvents, which finds favor in fluid food and supplement recipes. This property lets formulation teams sidestep cloudy precipitates and stubborn residues. It’s non-hygroscopic, so it flows well during processing and storage—a small blessing in any large-scale operation. Compared to inorganic salts, this chelated compound keeps its iron more bioavailable and less likely to trigger interactions that spoil taste or nutrition profiles.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Quality standards for ferrous lactate reflect the high stakes of iron supplementation. Both food and pharma suppliers must offer materials with clear proof of purity—often exceeding 98%—and tight control over heavy metals, moisture, and loss on drying. On product labels, you’ll usually see “Ferrous Lactate” or “iron(II) lactate,” sometimes alongside an E-number (E585) in regions following European rules. Certifications like USP, FCC, or E-number compliance matter to buyers in the food chain, as does country-specific documentation. Many markets require the explicit declaration of elemental iron content, origin, and intended function—fortification, enrichment, or color retention (in pickled vegetables, for example).

Preparation Method

Manufacturers start by fermenting carbohydrates like molasses or corn starch, yielding lactic acid through microbial action. After refining, the lactic acid solution undergoes neutralization using freshly prepared ferrous compounds such as ferrous carbonate or ferrous sulfate. Precise pH control is essential; stray too acidic, and you risk oxidizing iron or producing impurities. The mixture forms ferrous lactate, which is then filtered to remove insoluble artifacts and dried—often under vacuum or reduced oxygen—to guard against unwanted iron oxidation. Companies that master this practical chemistry get a product that’s both stable on the shelf and easy to handle at scale.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Iron(II) salts don’t play nice with air, light, or alkaline conditions. In storage, exposure to oxygen converts iron(II) to iron(III), dulling both color and nutritional value. That puts pressure on packaging and warehouse conditions. In certain functional foods or premixes, formulators wrap ferrous lactate in coatings—like food-grade waxes or polysaccharides—to slow this process. Some researchers tinker with additional chelators, like citric acid or ascorbic acid, not just to steady the iron but to boost absorption. Food technologists understand that, left unchecked in a product matrix, iron can catalyze fat oxidation and vitamin degradation, so the interplay of recipe design and ingredient protection becomes a daily game of chess.

Synonyms & Product Names

Depending on country or supplier, the ingredient might go by several handles, including iron(II) lactate, E585, Ferlactate, or Lactic Acid Iron(II) Salt. In food code rosters and pharmaceutical indexes, each synonym leads back to the same core molecule. Buyer attention focuses on documentation and proof, as interchanging variants or sources without proper validation risks both performance and compliance failures.

Safety & Operational Standards

Food authorities, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), grant ferrous lactate generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status when used in food-level amounts. Manufacturers stick to tight specs on iron content, limit trace contaminants, and monitor for bacterial safety. In the plant, iron salts must stay sealed and dry; airborne dust generates not just mess, but respiratory irritants for workers. Personal protective equipment (PPE), spill-resistant packaging, and proper ventilation become standard. Training addresses not just chemical safety but cross-contamination risks if production lines handle multiple fortificants.

Application Area

Ferrous lactate shows up in more places than most shoppers realize. Food and beverage companies reach for it to enrich juices, flour mixes, dairy drinks, and even herbal tonics. Color retention brings it into pickling and canning, where iron steers vegetable hues in the right direction. The pharmaceutical sector employs ferrous lactate in chewable tablets, syrups, and capsules aimed at treating or preventing iron-deficiency anemia. In animal nutrition, it finds a niche fortifying feeds for livestock and aquaculture where taste and absorption matter. Regulatory acceptance and the lack of metallic aftertaste open doors far beyond what many formulators expect.

Research & Development

Teams in both industry and academia continue to dissect the puzzle of iron delivery, bioavailability, and consumer acceptance. Recent research explores the potential of co-administering ferrous lactate with vitamin C or other oxide reducers to drive uptake. Others work on encapsulation techniques that shield iron from harsh gastric environments, offering timed release or “gentle” absorption. Nutritionists keep tracking interactions with phytates and polyphenols, common in plant-based diets, which can block iron absorption even from optimized compounds. The push toward plant-based, “clean label” solutions motivates deeper dives into fermentation methods and organic-coating approaches, aiming for ingredients that meet both efficacy goals and consumer demands for transparent sourcing.

Toxicity Research

Excess iron poses risks from oxidative damage and gastrointestinal irritation to chronic overload in sensitive populations. Toxicologists have mapped the acute and chronic thresholds for ferrous lactate, tying it close to total dietary iron limits. For instance, single-meal exposures in children carry the most worry, with overdose cases rare but serious. Most studies confirm that, at regulated intake levels, ferrous lactate shares the low-toxicity profile of other iron supplements. The main safety challenge lies in portion control, labeling clarity, and keeping iron-containing products out of reach of children, as outcomes from misuse can be dire.

Future Prospects

With the worldwide drive to combat micronutrient malnutrition, ferrous lactate has a chance to play a larger role, especially in regions where taste, tolerance, and shelf life challenge other iron sources. Next-generation product designers look to combine this salt with smart delivery systems and integrate it into more complex matrices, even including plant-based meat alternatives and advanced medical foods. As fortification programs scale and personalized nutrition keeps trending, the demand for stable, bioavailable iron options will likely grow, and ferrous lactate stands ready to fill gaps where taste, cost, and science align. The key lies in translating lab insights into manufacturing routines nimble enough to handle changing regulations, consumer habits, and the technical complexity of the modern food chain.

What is ferrous lactate used for?

What is Ferrous Lactate?

Ferrous lactate is a mineral compound that delivers iron, an essential nutrient. Anyone who has tried to keep energy levels up, or cares for someone with anemia, knows iron really matters. Low iron drags you down. That sluggish, foggy-headed feeling isn’t just in your head—it shows what happens when cells can’t do their job right because they lack oxygen. Ferrous lactate steps in as one of the food-safe iron sources that addresses these issues.

Food Fortification and Nutrition

Companies use ferrous lactate to boost the iron content of food. Grain products, breakfast cereals, baby formulas, snack bars, and even certain beverages often rely on it. This is not about adding something fancy—it’s about closing nutritional gaps. Ask any dietitian: not everyone gets the iron they need from food alone. Some people, especially teens, women and kids, risk deficiency because diets change, or because iron from plant sources doesn’t absorb as easily.

Food scientists know that adding iron can change color and taste. Ferrous lactate does a better job than many alternatives because it has a comparatively mild flavor in low concentrations. Shoppers probably have no idea it’s there, but it keeps food tasting like food, and not like a rusty pipe.

Aid in Iron Supplements

Pharmacies stock various iron pills and syrups for people diagnosed with anemia. Some brands use ferrous lactate as the main ingredient, especially in chewables or liquids for children who struggle to swallow tablets. Tablets sometimes create stomach discomfort, but ferrous lactate shows a lower chance of causing upset—partly because of its solubility.

Iron gets a bad rap for constipation and nausea. Many people quit taking supplements as soon as gut issues start. Using more easily tolerated forms, like ferrous lactate, addresses a real problem. Real-world adherence to iron treatment has serious consequences, from school performance in kids to birth outcomes for mothers.

Color Stabilizer in Foods

Pickles, olives, and canned vegetables—most people don’t realize those crisp green hues sometimes come from iron compounds. Ferrous lactate prevents “off color” changes that make food look less appetizing on store shelves. Producers sometimes add it to maintain green coloration in processed vegetables, lending appeal without using artificial color additives.

There’s also a role in meat substitutes. Plant-based burgers and sausage try to mimic real meat, part of which comes from the iron content. Using ferrous lactate achieves a more “meaty” look either by coloring alone or by replacing iron lost in processing.

Safety and Controversy

Most people tolerate ferrous lactate well because it breaks down easily and acts just as iron found in nature would. The FDA recognizes it as generally safe when used as intended. Doctors agree iron fortification addresses public health. The real challenge comes from getting enough, not getting too much, since iron toxicity from food takes exceedingly high doses rarely found outside supplements taken in error.

Transparency matters. Consumers want to know what’s in their food, particularly when it’s something they can’t easily pronounce. More brands now disclose the source and purpose of their ingredients, and nutrition labeling supports informed choices.

Practical Solutions for Better Iron Nutrition

Food insecurity and limited access to meat or leafy greens mean fortification remains crucial, especially for vulnerable groups. Adding iron to food is not a cure-all, but it’s a proven, practical way to make sure more people get enough of this vital nutrient. Policymakers, food producers, and health educators can do better by encouraging iron-rich diets along with responsible fortification, so no one loses out due to where they live or what’s in their fridge.

Is ferrous lactate safe for consumption?

Understanding Ferrous Lactate in Everyday Food

Open up a box of breakfast cereal and scan the nutrition label—iron, check. That iron often comes from additives like ferrous lactate. Food makers use it because it dissolves easily in water and adds a gentle boost of iron without changing the taste or color of food. That matters to me, especially after some health struggles left my iron levels low. My doctor recommended looking out for iron sources in food, and I started noticing ferrous lactate in ingredient lists everywhere, from pasta to snack bars.

Safety Backed by Research and Regulation

A big part of trusting any food additive comes from knowing who’s checking up on it. Health authorities, like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), review scientific research before allowing ingredients in food. Ferrous lactate doesn’t just show up overnight; studies examine its effects on the human body, how it gets absorbed, and any potential risks. The FDA lists it as “Generally Recognized as Safe”—a status earned after lots of data review, not just wishful thinking.

Iron itself is an essential mineral. Our bodies use iron to carry oxygen in the blood and keep energy up all day. Not getting enough iron leads to anemia, leaving people—or in my case, me—feeling tired and worn out. For folks more at risk, like pregnant women, kids, or people on plant-based diets, getting iron from food fortification (like ferrous lactate) can make a big difference.

Concerns Around Additives

Anything added to food raises some eyebrows. Ferrous lactate comes from lactic acid (yes, the same kind in yogurt) and iron salts combined in a lab. For anyone with a history of sensitivity to additives, or folks worried about synthetic ingredients, those long names can set off alarms. Most of the time, though, it breaks down easily in the stomach and does its job without drama. People with a rare condition called hemochromatosis—where too much iron builds up—do need to keep an eye on intake, but for most, ferrous lactate falls in safe territory.

Too much iron rarely comes from just food, but supplements stacked on top of fortified foods can push iron levels up quickly. Always helps to talk to a doctor before grabbing extra iron supplements, especially for kids or those on special diets.

Weighing the Benefits and Looking Ahead

Iron deficiency remains widespread—even in wealthier countries. Adding safe forms of iron, like ferrous lactate, can cut anemia rates. The World Health Organization backs food fortification as a simple, proven way to fight tiredness and weakness caused by low iron. Locally, I’ve seen schools offer iron-fortified meals as part of lunch programs, and the feedback from teachers and parents has been positive.

Some folks push for clear labeling and transparency, pointing out that not everyone wants extras in their food—even if they’re safe. More companies have started sharing exactly what goes in their food, which bridges the trust gap and lets people make informed choices. My own approach stays simple: I check labels, talk to my doctor, and look for food that fits my needs.

Keeping Safety Front and Center

Staying healthy means paying attention to what goes in your body and asking questions when something looks unfamiliar. Ferrous lactate stands on a solid base of good science and practical use. Regular reviews by health experts and food regulators help catch new information and keep safety up to date. Good health doesn’t always mean taking the most natural route—sometimes, it’s about balance and knowing what works for your body.

What are the side effects of ferrous lactate?

Experiencing Ferrous Lactate Firsthand

Taking care of iron levels isn't always as straightforward as picking up a supplement off the shelf. Ferrous lactate is one form of iron people take to bump up their iron stores, especially if they're dealing with anemia or low energy. I remember starting an iron supplement back in college because blood work showed I needed it. Ferrous lactate was one my doctor suggested thanks to its absorption rate and a slightly milder impact on digestion, at least compared to classic ferrous sulfate.

Common Side Effects in Daily Life

After a week, I noticed some disruptive symptoms. Stomach aches kicked in after breakfast. My appetite dropped, and I felt bloated. Many users report nausea or an uneasy stomach. Constipation hits most people pretty hard, and in my case, every trip to the bathroom proved the point—stools darkened and grew harder. Sometimes, diarrhea takes the place of constipation, but stomach discomfort remains a regular guest.

Metallic taste crept into my mouth after every dose. It didn’t matter if I took it with food or water, the aftertaste lingered for hours. Friends who tried different iron salts mentioned the same problem. An odd taste might sound trivial, but it starts affecting how you enjoy meals and drinks.

Long-Term Use Concerns

Mild symptoms bother most users and go away once the body adjusts or with changes to diet or dosing. That’s not the whole story, though. Long-term high iron intake sometimes builds up iron in organs. This overload brings fatigue, joint pain, or even liver problems in extreme cases. Some people, especially those with hereditary hemochromatosis, shouldn’t start iron therapy without detailed medical advice.

Allergic reactions—while rare—can’t be ignored. Signs like rash, trouble breathing, or swelling need urgent medical help. Mixing ferrous lactate with other medicines can block absorption or cause new side effects, which is why it’s smart to hand your full medication list to a doctor or pharmacist.

Looking for Ways to Ease the Impact

What worked for me was taking the supplement with food, even though that can shrink how much iron my body pulled in. Splitting the daily dose into two lighter ones calmed my stomach. Adding fiber-rich foods kept constipation away. Drinking lots of water and staying active also played their part. Some folks switch to a chewable or liquid if swallowing tablets felt rough, but each method brings its own set of ups and downs.

Doctors sometimes recommend taking vitamin C (like a glass of orange juice) next to iron pills. Vitamin C can help the body use iron better, making the most out of each dose. Talking with healthcare pros before making changes helps avoid mistakes.

Why Paying Attention to Side Effects Matters

Keeping an eye on how your body acts after starting ferrous lactate helps catch problems early. Routine blood checks track ferritin and hemoglobin levels so you don’t end up with too much iron. Sharing concerns or odd symptoms with your doctor keeps the treatment journey safe and effective. Iron deficiency shouldn’t be ignored, but neither should side effects. Paying attention helps each person find the right balance between health needs and daily comfort.

How should ferrous lactate be stored?

Understanding What Ferrous Lactate Needs

Anyone who’s spent time in a food lab or a supplement warehouse probably spotted ferrous lactate on a shelf, often labeled as a source of iron. This compound helps enrich cereals, beverages, and some medicines. People don’t talk about its storage as much as they should, but the way something like this gets handled really does matter. Ferrous lactate reacts to its environment – too much air or moisture turns it clumpy or dull, ruining its value. Every batch costs real money and wasted material sets companies back. So, rolling the dice on storage ends up as a bad bet.

Keep It Dry, Keep It Tight

Nothing ruins ferrous lactate faster than humidity. Dampness triggers its iron to break down and spoil the original look and mineral content. I’ve seen what a little moisture can do to fine powders; even with basic warehouse shelving, one weak plastic bag means the whole container clumps together at the bottom. That doesn’t just confuse the production line; it means tossing out inventory. So, sealed, moisture-resistant packaging belongs at the front of any storage plan. Polyethylene bags or lined drums outwork paper sacks every time. Good habits make the difference. Rolling the top of a bag and thinking that’s enough never works—you need a twist tie or a clamp, and secondary containers offer backup if someone gets careless.

Light Doesn’t Play Nice

Ferrous lactate changes color with light, a dead giveaway for a reaction taking place. If you’ve ever seen an open tub left near a sunny window, you know that pale green soon looks brownish. Some companies skip labeling storage bins, figuring a week in a warehouse doesn’t make a difference, but direct sunlight does more damage in those days than weeks in the dark. Steer clear of windows and overhead lights. Opaque containers solve this, and stashing products in a closed cabinet or storeroom helps a lot.

Temperature Swings Steal Potency

There’s a temptation in busy facilities to shove non-refrigerated compounds wherever they fit. Heat doesn’t just fade color; it can break chemical bonds. Even stash spots close to HVAC ducts bring problems—never mind summer heat waves or cold snaps. Consistent room temperature protects ferrous lactate best. In my early days managing a supplement stockroom, staff once left tubs next to a boiler. After a weekend, we had unusable product and a mess, all from ignoring a simple detail. Set storage in a temperate, stable room, away from those “hot spots” or draughty entryways.

Label Everything, Audit Often

One underrated trick: label every batch with clear use-by dates. Even if ferrous lactate sits untouched for months, a quick label check signals if a stockpile was forgotten or spoiled. Inventory logs catch mistakes before they leave the storeroom and guarantees nothing questionable lands in the next food lot. Audit storage shelves regularly—if anything looks clumpy, musty, or off-color, set it aside for disposal, not for blending.

Keeping Things Safe

Ferrous lactate won’t explode or evaporate, but good storage cuts accidental mix-ups with other powders and keeps workers safe. Keeping bags sealed and dry isn’t just about product lifespan—it stops spills, limits dust, and keeps everyone breathing easier. For facilities with kids or pets anywhere nearby, always place iron compounds out of reach. Training staff on basic storage rules seems simple, yet it avoids headaches and replacements that drain time and money.

Is ferrous lactate suitable for vegetarians or vegans?

What’s in Ferrous Lactate?

Scan the ingredient list of many fortified foods, and ferrous lactate can show up—usually listed as an iron additive that boosts nutrition in products, especially plant-based ones. Ferrous lactate is a compound made from iron and lactic acid. For anyone worried about getting enough iron, especially on a plant-focused diet, that looks like a plus at first glance.

Drawing the Line: Vegetarian and Vegan Concerns

Plenty of folks living a vegetarian or vegan lifestyle assume any mineral supplement must be meat-free. That sounds reasonable. In fact, the tricky part lies in where the lactic acid comes from. Lactic acid sounds like something from milk, but it doesn’t have to come from animal sources. Most of the time lactic acid used in food manufacturing comes out of fermenting carbohydrates from potatoes, corn, or beets with certain bacteria.

Still, manufacturing practices don’t always guarantee plant-based origins. Some companies may run fermentation on dairy-based sugars. Food labels rarely dive into that detail. I learned years ago while trying to cut out animal byproducts that these gray areas pop up a lot. It takes more than a glance at the nutrition label to know what you’re really eating.

Industry Standards and Iron's Importance

Iron matters a lot, especially in vegan and vegetarian diets, since plant-based sources of iron don’t absorb as easily as those in meat. About 10% of Americans run low on iron, with women and young kids most likely to get hit. The addition of iron fortification in foods like cereal and bread has helped lower rates of iron deficiency.

Food manufacturers know this, and often pick ferrous lactate because it blends well into foods and doesn’t create weird flavors or colors. The form of iron in ferrous lactate absorbs well, and it sidesteps the chalky taste that raw iron can bring to a product. If the lactic acid is plant-based, vegetarians and vegans benefit from added iron. That matters, since iron deficiency can lead to lower energy, trouble focusing, and even compromised immune function.

Finding Out the Source: Consumer Dilemmas

Anyone following a vegan diet long-term quickly learns the world of food additives is murky. Most companies aren’t eager to spell out their entire supply chain, and regulations in many countries let them get away with that. As someone who’s fielded questions at health food stores and sifted through ingredient lists for years, I’ve seen how often this sort of thing turns into a guessing game.

Groups like The Vegetarian Society or The Vegan Society often push for more transparency. They ask companies to confirm that lactic acid and similar compounds don’t come from animal products. Some brands listen—usually those that go the extra mile to market specifically to vegans.

Possible Solutions for Shoppers

For somebody who wants certainty, the best move is to look for products stamped with trusted labels like “Vegan” or “Vegetarian Society Approved.” If a food contains ferrous lactate and the company claims vegan-friendly status, that gives more confidence. People can also reach out to manufacturers to ask where their lactic acid comes from, though that method takes patience.

Raising your iron without risking animal products often means focusing mostly on whole plant foods, cooking with cast-iron pans, and picking supplements clearly marked as vegan. Ferrous lactate can fit a meat-free diet—but only if the source of each ingredient is clear and verified by a third party.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | iron(II) 2-hydroxypropanoate |

| Other names |

Iron(II) lactate Ferrous 2-hydroxypropanoate Iron lactate Lactic acid, iron(2+) salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈlæk.teɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | iron(II) 2-hydroxypropanoate |

| Other names |

Iron(II) lactate Ferrous 2-hydroxypropanoate Iron lactate E585 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈlæk.teɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 141-19-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3942624 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75831 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201564 |

| ChemSpider | 61925 |

| DrugBank | DB14875 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 08b1d4fb-cb46-48e9-9fb8-7f3c61cbd9d8 |

| EC Number | E585 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: **134025** |

| KEGG | C18625 |

| MeSH | D007503 |

| PubChem CID | 2723916 |

| RTECS number | OI8925000 |

| UNII | 9H3R4FH02V |

| UN number | UN3260 |

| CAS Number | 5905-52-2 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `Ferrous Lactate JSmol 3D model string`: ``` Fe+2.C6H10O6-2 ``` This is the **JSmol model string** for Ferrous Lactate: `"Fe+2.C6H10O6-2"` |

| Beilstein Reference | 3581877 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75832 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201511 |

| ChemSpider | 34500 |

| DrugBank | DB13922 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.021.541 |

| EC Number | 299-128-4 |

| Gmelin Reference | 60876 |

| KEGG | C02344 |

| MeSH | D007532 |

| PubChem CID | 24857 |

| RTECS number | OJ6300000 |

| UNII | 3S814V75CW |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2035977 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H10FeO6 |

| Molar mass | 325.03 g/mol |

| Appearance | Light greenish-white crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | D=1.50 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.3 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 8.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 5.29 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | 'Magnetic susceptibility (χ) of Ferrous Lactate: +1320 x 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol' |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.62 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 7.22 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H10FeO6 |

| Molar mass | 233.01 g/mol |

| Appearance | Light greenish yellow powder or crystals |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | D: 0.8 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.77 |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.6 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 3.7 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Paramagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.52 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 2.99 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 143.6 J⋅mol⁻¹⋅K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1572.2 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 212.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1597.2 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | B03AA03 |

| ATC code | B03AA08 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS labelling: Danger; H302 - Harmful if swallowed. H318 - Causes serious eye damage. P264, P270, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P310. |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Do not ingest. In case of inadequate ventilation, wear respiratory protection. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 3,260 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral-rat LD50: 3,250 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WX8750000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 25 mg/kg |

| REL (Recommended) | Max 210 mg/kg (as Fe), FSS (FPSFA) Regu. 3.1.6 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H315, H319, H335, P261, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H315: Causes skin irritation. H319: Causes serious eye irritation. H335: May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry, well-ventilated place. Avoid contact with skin and eyes. Wash thoroughly after handling. Do not breathe dust. Use personal protective equipment as required. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3,267 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 3,250 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | NL8500000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | FERROUS LACTATE: PEL (OSHA) - 15 mg/m3 (total dust), 5 mg/m3 (respirable fraction) (as iron salts, soluble) |

| REL (Recommended) | 10-60 mg daily |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Iron(II) sulfate Iron(II) gluconate Iron(III) lactate Ferrous fumarate Ferric chloride |

| Related compounds |

Iron(II) succinate Iron(II) fumarate Iron(II) gluconate Iron(II) malate Iron(II) sulfate |