Ferrous Carbonate: An In-Depth Look

Historical Development

Chemists first documented ferrous carbonate in the early 19th century, back when scientific exploration still wrestled with basic analytical tools. Natural deposits, mainly in the mineral siderite, have played an important role in the iron industry’s growing pains. Metallurgists quickly recognized its usefulness as both a source of iron and a pigment. Siderite’s widespread mining in Europe drove early experiments with ore beneficiation and chemical separation, setting the foundation for future technological advances. Over the years, laboratories refined extraction methods, and the compound crept into more specialized applications, including pharmaceutical and water treatment products. This gradual shift from raw ore to processed chemical underscores the way industries adapt and thrive on both scientific curiosity and economic necessity.

Product Overview

Ferrous carbonate, or iron(II) carbonate, is a pale, greenish powder in its pure form, known by chemists and industrial buyers as FeCO3. The compound shows up both in nature and as a synthetic product, and the way it handles both moisture and air exposure shapes how manufacturers pack, label, and transport it. Its role as a mild iron supplement in some medical settings has waxed and waned with changing trends in nutrition science, yet it manages to hold a place among raw materials for pigments and ceramics, and shows up in water treatments aimed at iron removal. Users encounter a mix of natural and synthetically derived forms, with their purity levels driving quality, price, and downstream suitability.

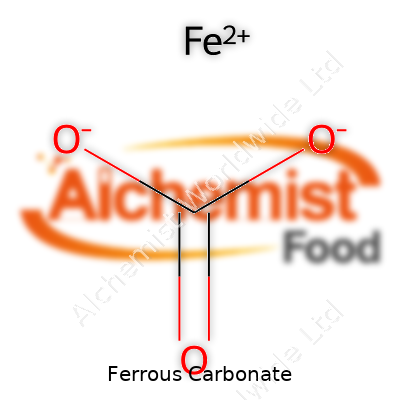

Physical & Chemical Properties

Pure ferrous carbonate offers a faint, earthy green color, thanks to ferrous (Fe2+) ions tightly bound to carbonate groups. It resists easy dissolution in water at room temperature, clumping or settling out of suspension. Exposure to oxygen ushers in slow oxidation, inexorably turning FeCO3 toward its more familiar, rust-red ferric oxide sibling. The compound remains odorless, and it reacts with strong acids to yield iron(II) salts and bubbling carbon dioxide. Chemists value its mild reactivity and note that it loses stability in air, which matters for storage and handling.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Labels on commercial ferrous carbonate list at least 95% assay, with measured iron content noted in percent by weight. Common contaminants include silicates, sulfates, and trace metals, often flagged with strict thresholds for pharmaceutical or food applications. Particle size ranges and moisture content get their own line-items, shaping shelf life and blending behavior. Packaging wraps the powder in airtight containers, guarded from both humidity and errant light. Industry standards, such as those specified in USP or FCC monographs, lay down expectations for everything from iron assay to lead limits, shaping procurement across food, pharmaceutical, and chemical sectors.

Preparation Method

Most plants generate ferrous carbonate through a straightforward reaction: moist iron(II) sulfate solution reacts with sodium carbonate or sodium bicarbonate. The pale green FeCO3 drops out, ready for filtration and washing. Careful exclusion of oxygen throughout this process keeps unwanted oxidation in check. Some labs explore routes that tweak pH or add minor stabilizers, especially when seeking pharmaceutical grade iron or when special particle sizes are in demand. Sourcing clean starting materials and scrupulous washing after precipitation go a long way toward reaching high purity grades.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Ferrous carbonate’s chemistry pivots around its instability in air. If you heat it gently, it sheds carbon dioxide, sliding to iron(II) oxide and slowly darkening in color. Acid solutions trigger fizzy, visible reactions, leaving iron(II) salts behind. Some water treatment setups convert FeCO3 on-site to get fresh, highly active iron for scavenging impurities. In pigment work, processing tweaks—like calcining—shift hues or compositional profiles. Industry-focused modifications tweak particle surfaces or stabilize the powder against caking and premature oxidation, as end markets dictate.

Synonyms & Product Names

Ferrous carbonate pops up in paperwork and supply catalogs under more names than most casual users realize: iron(II) carbonate, Ferrosi carbonas, and the mineralogical name siderite. Legacy nomenclature from old chemical treatises—like chalybite—still lingers. Some suppliers use their own trade names, hoping to stand out in a commodity-driven landscape, but regulatory paperwork circles back to standard IUPAC and pharmacopoeia listings.

Safety & Operational Standards

Industrial and laboratory handlers wear gloves, protective eyewear, and respirators when dust risks run high. Written safety protocols stress dry storage and close container sealing to halt unwanted oxidation. Ferrous carbonate ranks as mildly toxic, mostly if inhaled or ingested in nonpharmaceutical doses. Storage away from oxidizers, strong acids, and food items reduces risk. Most regions classify it as non-hazardous for transport under normal conditions, though spill management rules demand prompt cleanup and reporting. Training doubles as a buffer against both contamination and workplace accidents, especially in batch operations or when handling bulk sacks.

Application Area

Ferrous carbonate takes on many jobs. In ceramics and glass, it brings iron’s earthy, mellow colors. Municipal and industrial water plants rely on its iron to knock out unwanted compounds from drinking sources. Nutritionists at times lean on it as a mild oral iron source, though better-absorbed forms see wider use. Mining companies and metallurgists still treat siderite as a practical ore, especially when pricing swings bump hematite or magnetite beyond reach. Paint makers chase specialized colors, where subtle shifts in FeCO3 purity or crystal habit can make or break a hue. Each field demands tight control of supply, particle behaviors, and purity, underscoring the need for rock-solid quality assurance.

Research & Development

Academic labs and corporate R&D both see ferrous carbonate as fertile ground for new discoveries. Current projects probe water purification advances, using the compound’s unique iron release profile to capture heavy metals and organic toxins. Cosmetic technologists experiment with microencapsulated iron for skincare and topical delivery. Battery designers think about new roles for iron-based compounds, seeking breakthroughs in sustainable electrodes and recycling processes. Better stabilization methods get attention, as small tweaks help ferrous carbonate last longer on shelves or in challenging climates. Real progress also happens on the manufacturing front, with pilot plant operators adjusting process steps, aiming for higher purity yields, greener chemistries, and less waste.

Toxicity Research

Early animal studies flagged moderate oral toxicity, raising caution flags for pharmaceutical use. Later research dissected how the body absorbs, stores, and eliminates iron from FeCO3, and the results suggest that bioavailability lags behind ferrous sulfate or gluconate. At the same time, accidental inhalation or ingestion outside controlled doses can irritate mucous membranes and trigger systemic overload. Updated toxicological reviews in regulatory submissions track chronic exposure, short-term risk, and environmental persistence. There’s ongoing work to pin down safe occupational exposure levels, especially for workers who mix or transport ferrous carbonate by the ton. Medical researchers continue looking for new ways to safely harness the compound’s gentle iron release, with the hope of sidestepping both iron deficiency and overload.

Future Prospects

Better control of ferrous carbonate’s properties could unlock new technical uses, especially in water treatment systems or as a green precursor in electronics. Sustainability pressures nudge R&D teams toward manufacturing methods with smaller carbon footprints and less chemical waste. Regulatory shifts may open new medical applications, where stable, slow-release iron sources gain fresh regulatory acceptance. As pigment markets search for natural, environmentally benign colorants, ferrous carbonate’s earth-tone hues look ever more appealing. Whole sectors—including energy storage and smart ceramics—could find themselves relying on old compounds like FeCO3, freshly tuned for modern applications. The challenge and opportunity both sit in the details: making, stabilizing, and using this honest, workhorse chemical with greater safety and flexibility.

What is Ferrous Carbonate used for?

Understanding the Use of Ferrous Carbonate

Ferrous carbonate sometimes gets overlooked among iron compounds, but its value keeps showing up in real-world places. The old chemistry books point to it as a greenish powder but in practice, it finds work both in industry and in clinics. I grew up around an agricultural community that relied on different feed additives, so seeing bags of ferrous carbonate in a feed mill felt ordinary to me. Looking back, there’s good reason for that.

Roots in Agriculture and Animal Nutrition

Iron deficiency isn't just a human problem. Livestock can run low as well, especially pigs and young calves. Ferrous carbonate enters the scene here. Mixing it into feed, farmers help prevent anemia—a concern when animals start looking listless and stop growing as expected. This isn’t guesswork; veterinarians rely on countable gains when animals receive the right dose. In my own experience with family friends who raised pigs, there was a clear difference in vigor after supplementing iron. Ferrous carbonate, being milder than some other forms, makes it possible to ease iron in without as much risk of digestive problems or taste issues that could turn animals off their food.

Role in Medicine

Iron deficiency takes a different form in humans. Pills made with ferrous carbonate are handed out to folks with iron-poor blood because this compound has a lower tendency to upset the stomach compared to some alternatives. I remember people in my community who struggled with other iron supplements but found ferrous carbonate easier to handle, sticking with doctor's orders for longer stretches. This isn't anecdote alone. Scientific studies back up slower, steadier increases in iron stores with fewer abrupt side effects, especially for the elderly or those recovering from illness.

Industrial and Chemical Uses

Beyond food and medicine, ferrous carbonate also has its hands in manufacturing. It acts as a pigment in certain ceramics and glass, giving greens and browns that wouldn’t be possible without it. On a construction site I once worked, stained tiles baked from iron-rich compounds still showed the subtle difference between synthetic pigments and the muted color of natural ferrous carbonate. Chemists also use it as an intermediate, preparing other iron compounds for things like water treatment or unique alloys.

Challenges and Solutions

Ferrous carbonate isn’t perfect. It oxidizes in air, turning brown as it changes into ferric compounds that aren’t as helpful for nutrition. Anyone who’s handled those greenish powders knows the frustration of opening a container only to find rust-brown clumps inside. Packaging in airtight bags and producing fresh batches closer to where it's needed helps cut down on waste. The feed companies near my hometown have always stressed quick turnover for this reason.

Environmental concerns stack up as well. Iron runoff from over-supplementing can cause algae blooms in farm ponds or small streams, a problem I saw first-hand one summer. Educational outreach and better measurement at the farm level gave local producers tools to stay within safe bounds while still meeting the health needs of their animals.

Wrapping Up with Practicality

Ferrous carbonate keeps finding use because it balances risk, cost, and usability. Livestock, human health, and industry all lean on it, even if most folks don’t notice. Watching its journey from a bag in the mill to a supplement bottle at the pharmacy shelf reminds me that even a plain green powder can have a pretty big footprint. Honest conversations about its strengths and weaknesses let people use it more wisely, which is good for animals, people, and the places we all call home.

What are the potential side effects of Ferrous Carbonate?

Why Folks Use Ferrous Carbonate

Doctors often recommend ferrous carbonate for folks who struggle with iron-deficiency anemia. Iron plays a big role in keeping blood healthy, carrying oxygen, and supporting energy. Eating leafy greens and meat sometimes isn’t enough, so supplements like ferrous carbonate come into play. This supplement makes sense for people with heavy periods, chronic illness, or certain diets. Still, every pill comes with trade-offs, and understanding what could go wrong means fewer surprises and better conversations with your health provider.

Stomach Trouble and Digestive Discomfort

Iron can be tough on the belly. Ferrous carbonate pills tend to bring along nausea, bloating, stomach cramps, and constipation. Some people talk about sharp cramps that show up after taking their daily dose, sending them scrambling for ginger tea or fiber-rich foods. Diarrhea could also surprise some users. Lots of folks I know have tried taking their iron supplement with food, even though this can dampen absorption. Others split doses, drinking more water to avoid trouble. Changing brands or iron types sometimes helps if the side effects get too annoying.

Changes in Stool and Teeth

After using ferrous carbonate, some people notice dark stools—almost black at times. This spooks people who aren’t prepared for it, but it’s actually pretty common. It doesn’t mean anything dangerous is happening, but it does make it hard for doctors to check for certain problems like hidden blood in the stool. Parents with young kids using liquid forms of iron sometimes see stained teeth. Brushing right after taking the medicine or using a straw for liquids can make a difference.

Potential Allergic Reactions

Rarely, ferrous carbonate triggers allergic reactions like hives, swelling, or trouble breathing. Anyone who notices these symptoms needs to get medical help fast. In all my years around hospitals, seeing a true iron allergy is rare, but nobody wants to gamble with shortness of breath or swelling.

Overdose and Iron Toxicity

Taking more iron than needed can cause big trouble. Iron overdose brings symptoms like dizziness, vomiting, rapid heartbeat, and, in serious cases, organ damage. I remember stories from emergency medicine, with parents rushing in after a child accidentally swallowed “just a few” adult iron pills. Iron is especially toxic to children. Keeping bottles high up and locked away prevents these accidents. Always measuring the right dose and talking to a doctor before adjusting pills cuts the risk, too.

Risks for People with Other Health Conditions

People with certain health problems—like hemochromatosis or liver issues—run bigger risks when using any form of iron supplement. Excess iron builds up in the organs, putting strain on the liver and heart over time. Regular blood work and check-ins with a health provider give peace of mind and catch any creeping problems before they turn serious.

Finding the Balance

Ferrous carbonate helps many people feel stronger, beat fatigue, and get back to their lives. At the same time, the side effects remind us that no supplement is a magic fix. Honest conversations with healthcare providers, regular monitoring, and a willingness to make changes if something feels wrong keep iron therapy safe. Most folks can avoid big trouble by respecting the power behind these little tablets and sticking with good advice from trusted sources.

How should Ferrous Carbonate be taken or administered?

Listening to the Doctor’s Instructions

Most folks stop paying close attention to their prescriptions after the first or second read-through. I get it—labels can blur together after a tough day, and no one wants to fuss over medication. With ferrous carbonate, skipping over the details means the iron might not work as well, and people could end up feeling worse instead of better. Personally, family members who've struggled with iron issues needed clear steps from the pharmacist and sometimes had to ask more questions—it made all the difference.

Why Timing and Food Matter

The body doesn't absorb iron from this supplement the same way every time. Taking ferrous carbonate on an empty stomach often leads to better absorption. Acid in the stomach helps iron get into the bloodstream more easily. Trouble is, that also means a greater chance of an upset stomach or even nausea. Some foods—especially dairy or high-fiber meals—make it harder for iron to do its thing. Even a simple glass of milk can cut down how much iron gets absorbed.

People who find the empty-stomach approach tough, especially if they already deal with nausea, can eat a small amount of food (just nothing heavy on calcium or bran). Experience in my own circles reminds me: plain crackers or a slice of bread can do enough to settle the stomach without ruining absorption. The best time of day tends to be in the morning or between meals.

Sticking to the Right Dose

Confusion about dosage happens more often than people expect, especially among the elderly or those juggling multiple prescriptions. Too much iron carries risk—liver strain, stomach pain, even toxicity in rare cases. Not enough, and you'll still feel the exhaustion and dizziness anemia brings. Most health care professionals base the dose on blood work. Skipping doses, doubling up after forgetting, or sharing with someone else throws off the balance. To stay on track, people sometimes set reminders or use pill organizers. Modern smartphones offer easy alarm settings for those who want extra help.

Pairing with Vitamin C

Vitamin C, whether in a supplement or straight from a glass of orange juice, helps the gut absorb iron. Studies and major medical sources back this up. Growing up, I saw doctors at community clinics telling patients to drink their dose down with juice instead of water. This simple move can mean the difference between normal iron levels and ongoing fatigue.

Possible Side Effects and What to Watch For

Stomach problems don’t surprise anyone who’s taken ferrous carbonate regularly. Constipation and black stools crop up most often—these changes usually don’t mean danger, but they do cause concern for people who haven’t seen them before. Real red flags: strong stomach pain, vomiting, or signs of an allergic reaction. If any of that shows up, getting back to a doctor fast matters. Trusted sites, like Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic, echo these warnings.

Final Thoughts on Asking for Help

No one manages supplements perfectly on the first try. Pharmacies and primary care clinics see questions about iron all the time. In my experience, the people who ask for clarity about timing, food, and side effects get results faster and feel better sooner. Googling advice can help, but nothing beats actual guidance from a trusted health care professional.

Are there any interactions between Ferrous Carbonate and other medications?

The Real Risks in Blending Iron with Other Drugs

Many folks turn to supplements like ferrous carbonate to help with iron deficiency and anemia, thinking it’s a simple fix. Sometimes, things get complicated when mixing medications. When you’re juggling prescriptions—maybe a blood pressure pill in the morning, iron at lunch, and an antacid in between—real problems can sneak up. Having spent years seeing patients and reading medical journals, I learned that iron rarely acts alone in the body.

Common Meds That Can Trip You Up

It’s easy to think a basic mineral won’t mess with other medicines. The truth says otherwise. Doctors and pharmacists watch for a few classic troublemakers. Tetracycline and doxycycline—two antibiotics—don’t play nice with iron. If you take them together, absorption goes down. Your infection stays longer and your iron doesn’t help like it should. The science behind this combination points to a kind of chemical tug-of-war in your gut. Calcium supplements and even simple antacids run into the same fight for space and attention inside the stomach. Your body just can’t take in everything at full strength.

Thyroid meds like levothyroxine get snagged by iron too. I’ve seen folks battle low energy and wonder why their thyroid pill stopped doing its job. Dig into the details, and you’ll find the real culprit usually hides in the daily pill routine—those two meds cross each other, sometimes just hours apart, and ruin each other’s impact.

Warfarin, Penicillamine, and Other Less-Known Conflicts

People taking blood thinners like warfarin want steady results. Adding iron upsets those numbers, affecting clotting time. Penicillamine—sometimes used for rheumatoid arthritis or Wilson’s disease—needs careful timing if it shares space with iron. Absorption plummets and treatment falters. I read more than one case where doctors had to track down strange lab results, only to find the answer in a forgotten supplement bottle.

Practical Steps That Work

Confusion comes from endless lists and warnings, but solving these problems rarely means giving up a needed pill or supplement. I often tell people to space iron and conflicting meds by at least two hours—or take iron on an empty stomach if possible. Let that supplement ride solo, then wait before reaching for anything else. A little separation lets your body get the full good out of both drugs.

Reading up on interactions matters. The FDA puts out clear guides, and pharmacists have full access to drug reference tools. Bringing your full medication list to every doctor visit helps, too. I’ve watched pharmacists catch mistakes, saving people weeks of feeling tired or sick. Personal experience doesn’t replace solid facts, so don’t just trust your memory or a quick internet search.

Consider Food, Not Only Pills

Anyone who’s tried to boost iron knows vitamin C helps absorption, but tea and coffee have the opposite effect. Same story with high-calcium dairy at breakfast—take iron away from that milk or yogurt. Reading nutrition labels can make a surprising difference. Health hinges on knowing what you eat, just as much as what goes into your medicine organizer.

Online Pharmacies Raise the Stakes

Ordering prescriptions online means less human contact. Fewer warnings make it to the average person. Many people miss questions about supplements during checkout. Staying informed comes down to asking the right questions and not skipping those info sheets. Your doctor and pharmacist sit on your team, not just behind a counter.

Who should not take Ferrous Carbonate?

Some People Face Risks with Iron Supplements

I’ve met plenty of folks searching for a quick boost in iron through supplements. Ferrous carbonate is one of the names that often comes up. It feels straightforward to just pick up an iron pill at the pharmacy and go on with the day. That works for many, but not everyone’s body treats extra iron in the same way. I once saw a neighbor end up with serious stomach pain and vomiting after adding an iron supplement, not knowing her underlying health problem made it unsafe. Stories like hers stick with me.

Those with Iron Overload Conditions Can Get Into Trouble

Some people have a tough time clearing out extra iron. Hemochromatosis leads to iron building up in organs, causing real damage over time. People with this genetic disorder need to avoid extra iron since their bodies already hang onto too much. Loading up on ferrous carbonate can speed up organ damage. Studies estimate hemochromatosis impacts about 1 in 200 to 300 people of Northern European descent. It often goes undetected until symptoms become serious. Doctors usually direct these patients to stay far away from standard iron tablets.

Iron Doesn’t Mix Well With Certain Medical Issues

People with certain infections, like those dealing with active bacteria in the bloodstream, can feed the germs with excess iron. Bacterial growth speeds up in an iron-rich environment. Individuals with peptic ulcers or chronic inflammatory conditions—especially affecting the stomach or intestines—may find that ferrous carbonate makes the situation worse. For these people, extra iron leads to more pain, cramping, and in some cases, bleeding. Patients on dialysis or those with kidney failure have different needs, too. Giving extra iron without close monitoring can mean trouble, because iron can pile up in tissues.

Some Medications and Treatments Clash with Iron

People taking certain antibiotics or medications for their thyroid need to think twice before adding an iron supplement. Iron can block the absorption of key drugs, making them less effective. This problem shows up a lot with levothyroxine for thyroid issues. Iron pills can also lower the absorption of medicines used to treat infections. Taking these medications at different times or avoiding supplemental iron altogether becomes important if a doctor’s treating an ongoing problem with a crucial drug.

Children and Accidental Poisoning Risks

Ferrous carbonate supplements hold serious risk for young kids. Even small amounts can poison a child, leading to vomiting, diarrhea, and organ damage. Some of the worst outcomes come from children accidentally swallowing adult iron tablets. Every year, poison control centers warn parents about storing supplements out of reach, and for good reason. No supplement should replace talking to a pediatrician about iron levels for a child.

Looking for Safe Ways to Treat Iron Deficiency

Starting a new supplement, including ferrous carbonate, works out best with help from a healthcare professional. Testing blood first shows if someone genuinely needs extra iron. Iron-deficiency anemia often responds well to changes in diet and targeted supplements if the cause is clear. If common symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath, or pale skin show up, doctors can investigate before any pills head home from the store. Sticking close to medical guidance keeps people safe and avoids the downsides that come with treating iron levels blindly.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Iron(II) carbonate |

| Other names |

Iron(II) carbonate Ferrous monocarbonate Iron carbonate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈkɑː.bən.eɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Iron(II) carbonate |

| Other names |

Iron(II) carbonate Ferrous monocarbonate Iron carbonate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈfɛr.əs ˈkɑː.bən.eɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 563-71-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3569617 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75831 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1208656 |

| ChemSpider | 21387 |

| DrugBank | DB11075 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.704 |

| EC Number | 231-835-0 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: 14252 |

| KEGG | C18704 |

| MeSH | D005261 |

| PubChem CID | 10118381 |

| RTECS number | NO5600000 |

| UNII | F895V5Y76A |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 563-71-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 2439790 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:75831 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201110 |

| ChemSpider | 22933 |

| DrugBank | DB13933 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.013.789 |

| EC Number | 209-154-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | Gmelin Reference: **13106** |

| KEGG | C07325 |

| MeSH | D005266 |

| PubChem CID | 10176878 |

| RTECS number | NO4560000 |

| UNII | 7HQX9NWM1K |

| UN number | UN3089 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | FeCO3 |

| Molar mass | 115.854 g/mol |

| Appearance | greyish white powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.96 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | -2.43 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 9.5 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +2540.0e-6 cm³/mol |

| Dipole moment | 0.00 D |

| Chemical formula | FeCO3 |

| Molar mass | 115.854 g/mol |

| Appearance | Grayish-white or light gray powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.96 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Slightly soluble |

| log P | -0.04 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 9.5 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.23 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +4360.0e-6 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.7 |

| Viscosity | Viscosity: 5-10 cP |

| Dipole moment | 0 Debye |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 88.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -678.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -825.1 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 83.9 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -739.0 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −751.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | B03AA03 |

| ATC code | B03AA03 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May be harmful if swallowed; may cause irritation to skin, eyes, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 2,250 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat 525 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | SC7500000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 3 mg/kg |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes irritation to skin, eyes, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: "H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 964 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral 1,800 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | N0395 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg Fe/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 50 mg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Iron(II) oxide Iron(II) hydroxide Iron(III) carbonate Ferrous sulfate Iron(III) oxide |

| Related compounds |

Ferrous sulfate Iron(II) chloride Iron(II) oxide Iron(II) acetate Iron(III) carbonate |