Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt: More Than a Lab Staple

Tracing the Road: Historical Development

Curiosity and persistence built modern chemistry, and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, known as EDTA disodium, took shape in the early 20th century as a chelating agent. F. Münz first synthesized EDTA around 1935, chasing a better choice for separating rare earth metals. That need still pops up today, except now labs use gallons of this stuff for everything from cleaning up heavy metals to boosting the shelf-life of food. EDTA’s roll-out tied closely to industrial innovation during those postwar decades—water softening stood out, plus cleaning products and pharmaceuticals got a reliable helper for all sorts of tasks. Once industries realized you could tie up metal ions and stop them from messing with reactions or quality, the chemical quickly jumped out of the research lab and landed in hospital supply closets, factories, even your toothpaste.

Product Overview

EDTA disodium can look pretty plain as a white crystalline powder, but its value stretches far beyond the shelf. The salt comes from mixing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid with sodium hydroxide, which makes it easier to dissolve. Inside labs, it mops up stray metals, keeping things clean and reliable, especially where metal ions could wreck the work. In real life, just about every hospital, water treatment facility, and textile factory depends on batches of EDTA—each one chasing better control, safer procedures, or clearer results. If you ever needed to scrub scale out of your coffee maker or guarantee a stable medicine, EDTA was probably there behind the scenes.

Physical & Chemical Properties

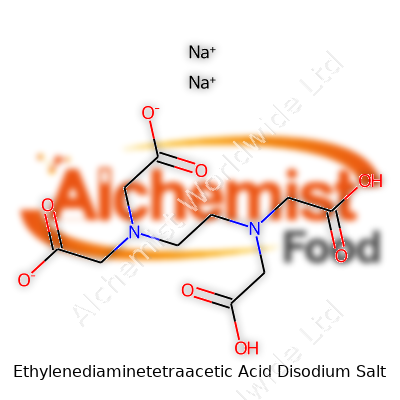

At room temperature, EDTA disodium appears as fine, snow-white crystals with no smell. Water picks it up easily, though solutions take careful mixing to stay clear. Unlike acids that bite at skin or metals, this salt feels bland—you could touch it and barely notice. Its melting point lands above 240°C, with decomposition taking over before you reach boiling. The formula, C10H14N2Na2O8·2H2O, hints at complexity, with four carboxyl groups and two nitrogen atoms waiting to tangle up with metallic visitors. Chemists count on its strong affinity for lead, iron, calcium, magnesium, and a long list of other metals. Without this reliable binding, lots of scientific measurements or industrial steps simply wouldn’t work.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Buying EDTA disodium usually includes a certificate spelling out purity—often at least 99%. Impurities like iron, heavy metals, or water content demand careful control, especially for pharmaceuticals or lab analysis. Packing materials use thick plastics or fiber drums to steer clear of contamination. Labels give weight, batch number, production date, and technical grades, usually noting whether it works for food, industrial, or analytical applications. All that fuss tracks back to how even trace amounts of unwanted ions could mess up a result or start a chain reaction somewhere no one intended. In my years around chemistry benches, everyone learned early that label details mean the difference between a reliable process and a sticky, expensive mess.

Preparation Method

Making EDTA disodium runs through a set path: start with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, add enough sodium hydroxide to neutralize all acidic protons, and then let the mix dissolve. For big production runs, manufacturers batch-react the acid with solution-phase caustic soda, removing byproducts through filtration. After that, they let the crystals dry and grind them as needed. Students in teaching labs often perform this preparation at small scale—everyone learns quickly that over-neutralizing leads to mush, and not enough caustic soda leaves a stubborn sludge. Modern plants automate most of this, chasing both purity and efficiency, but the basic chemistry traces back to first-year experiments in glass beakers.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

EDTA disodium thrives on coordination chemistry. Once dissolved, its molecular tentacles wrap up loose metals, forming tight, water-soluble complexes. Analytical labs add it to solutions to remove calcium, iron, magnesium, or other troublemakers that would otherwise skew results. In industry, EDTA’s ability to grab and hold rare earth elements brought it to the center of many extraction processes. Researchers tinker with the basic structure, swapping sodium ions for potassium or ammonium ones, or attaching fluorescent tags for biomedical imaging. Sometimes, companies build derivatives with different solubility, controlling the speed and reliability of chelation. Every modification chases either new safety profiles, greater affinity for specific ions, or just a better fit for a demanding job.

Synonyms & Product Names

Nobody likes to stumble over a mouthful, so EDTA disodium also passes as Disodium EDTA, Edetate Disodium, Ethylenediaminetetraacetate Disodium Salt, or even Na2EDTA. Some suppliers give it catchy trade names, but in the lab or the shop, EDTA keeps its reputation by performance more than branding. Pharmacists see it as Edetate Disodium USP or BP grade, food technologists scan for E386 on ingredient lists, and chemists fall back on the familiar abbreviation to save time. At every step, the meaning stays the same—a tough, reliable chelator that keeps things running smoothly.

Safety & Operational Standards

EDTA disodium doesn’t act aggressively—it rarely causes skin irritation, and inhalation risks stay low in normal environments. Still, workers use gloves, dust masks, and goggles during big batch handling to steer clear of dust clouds. The compound needs storage in dry, sealed containers far from strong acids or oxidizers. In medical use, the dose and application stay strictly regulated because, although chelation cares for heavy metal poisoning, too much can upset levels for calcium and other needed metals in the blood. Water treatment operators watch downstream effects as EDTA complexes sometimes survive processing, hinting at real risks if they end up in rivers and lakes. Rules on discharge, binding methods, and safer-handling protocols evolved for good reason—it took years and plenty of lessons before these standards landed in rulebooks.

Application Area

EDTA disodium crops up everywhere. Medical teams fight lead poisoning or manage certain heart conditions with controlled chelation therapy. Dentists rely on it to irrigate root canals and prevent calcification. Foods like canned beans, mayonnaise, and soft drinks taste fresher for longer because traces keep metals from catalyzing spoilage or color changes. Labs can barely function without EDTA—it keeps analyses consistent from water hardness checks to blood chemistry. Textile and paper factories lean on it to soften water and prevent metal-caused discoloration. Pool cleaning, wine making, photography—all pick up this compound for a simple reason: controlling rogue ions lets people chase better results, less waste, and fewer headaches.

Research & Development

Researchers focus attention on two big goals—sharper selectivity and environmental safety. Modified EDTA versions are in the pipeline that only bind specific metals, hoping to avoid carpet-bombing helpful ions or upset delicate industrial balances. In medicine, the target lies with gentler, safer chelation routines, since even standard EDTA can disrupt mineral balances if used too aggressively. Green chemistry approaches test whether enzymes, microbes, or plant extracts could break down EDTA after use, blocking its slow spread in rivers. Real progress takes honest reporting, patient trials, and tight collaboration, because the old formula only works for so long before soils, waterways, and supply chains push back.

Toxicity Research

Animal studies and clinical use both underline that EDTA itself isn’t acutely toxic, but long-term or high-dose exposure strips out not just lead or arsenic, but also healthy metals like calcium, zinc, and manganese. That’s led regulators to set acute reference limits for humans—safe in therapeutic doses, tricky if mishandled. Environmental research flags an entirely different headache: EDTA complexes move easily through water and resist breakdown, sometimes making it easier for heavy metals to travel and accumulate where people least want them. Biodegradation stays slow, so cleanup or containment keeps cropping up as a concern, especially near large-scale users. Regulators ask for technology-based standards in water treatment plants and careful logging of downstream impacts. If experience teaches anything, it’s that new pieces of the puzzle keep landing as industries evolve and uses spread out.

Future Prospects

The next chapter for EDTA disodium looks both promising and challenging. Old industries continue depending on its reliability, but new innovations—battery technology, targeted medicine, and sustainable agriculture—keep demanding variants that fit tighter profiles. There’s movement toward engineered chelators that break down faster or target only one metal in busy mixtures. Green chemistry keeps calling for substitutes and strategies to cut down persistence and migration in the environment. Personal experience using EDTA in crowded teaching labs, industry audits, and project troubleshooting always came with tight checklists—the margin for error narrows as regulations climb and client expectations grow. As research rolls out fresh alternatives, no single magic bullet solves every issue, but each step learns from lessons written in lab books and waterway reports going back decades.

What is Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt used for?

Why People Care About EDTA Disodium Salt

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, or EDTA disodium, pops up in more places than most folks realize. Some of us encounter it in the medical world, others in the science lab, and many brush right past it in household products. So, why does it matter so much? In my own time working in both research and healthcare settings, I've watched plenty of experts reach for a bottle labeled EDTA, not because of habit, but because nothing else quite replaces what it does.

Packed Into Everyday Products

Anybody who’s mixed paint, checked the ingredient list for shampoos, or worried about the shelf life of packaged food has probably dealt with EDTA disodium salt. Manufacturers rely on it to keep colors stable and stop metals from messing with products. That means less spoilage, fewer weird textures, and better results from simple things like laundry detergent. As someone who’s ruined a favorite shirt thanks to rusty water, I get why this matters. Water supplies often carry impurities like iron and copper. EDTA binds to those metals and keeps them from reacting with the cleaning agents, so your whites stay white, not vaguely yellow.

The Pillar of Many Medical Treatments

Medicine gets even more personal. In hospitals, EDTA shows up as a blood anticoagulant, especially when labs need a clear look at blood cell health or want to run certain types of tests. This isn’t some theoretical safety net; people rely on it for accurate results, whether they’re checking for anemia or planning for surgery. It also plays a key role in chelation therapy for lead poisoning, pulling heavy metals out of the bloodstream so damage doesn't build up in vulnerable organs. I’ve seen worried parents relieved to learn that their child’s lead exposure could be tackled head-on thanks to this compound.

Laboratory and Industry Dependence

Any busy lab—whether in a pharmaceutical company, university, or municipal water plant—leans on the stability EDTA gives to solutions. Without it, enzymes in a test tube break down, samples turn unreliable, and a week's worth of data goes straight into the trash. That reliability is worth its weight, since even small changes in a chemical mix can skew results. People working with textiles, paper, and even photography notice similar effects. Paper gets brigher, dyed fabrics keep their hue, and photographers avoid unexpected discoloration because metals, instead of running wild, get locked down by EDTA.

Concerns and Choices Moving Forward

Every widely used chemical comes with baggage. Some studies point to environmental build-up once EDTA runs down the drain. Wastewater plants struggle to break it down. That means more effort to limit how much escapes into rivers and lakes. There’s push for greener chelating agents, but right now alternatives can be pricey or less reliable, leading factories and labs to stick with what works. In my own experience working with scientists searching for substitutes, many either cost too much or come with trade-offs that make them impractical for large-scale use.

The Path to Smarter Use

Solutions start with better recycling and stricter controls at the factory level. Some experts call for tighter standards on disposal, especially from plants that release more byproducts. Switching to less persistent alternatives wherever possible offers another layer of protection, but to really move away from EDTA, research must keep up with industry’s real-world needs. People depend on safe water, healthy food, and reliable medicine. Until something better arrives, EDTA’s spot in the world runs deep.

What are the safety precautions when handling Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt?

Understanding the Risks

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt—often called EDTA disodium salt—shows up in lots of workplaces. From labs to factories, I’ve seen it lend a hand softening water and cleaning metal ions from solutions. While it’s not the most dangerous chemical out there, nobody can afford to treat it casually.

Personal Experience and the Human Side

I’ve watched lab newbies rush into handling EDTA disodium salt without thinking much about safety. Maybe it’s the bland, white powdery look that tricks people into thinking it’s harmless. I made that mistake just once. My skin felt irritated after contact, teaching me caution the hard way. Over the years, I learned to respect every chemical on the shelf, even those without a warning smell.

Basic Precautions Matter

Too many people skip gloves, but that simple barrier cuts down unexpected rashes or dryness. Nitrile gloves work just fine. Safety goggles belong on your face, not on the table. Even a tiny speck in the eye can turn a quiet day into an urgent run for the eyewash station. Anyone sharing lab benches should also make a habit of wearing cotton lab coats—it keeps powder off your clothes, which means fewer worries about exposure after work.

Mixing or weighing out the salt can create dust. It doesn’t take much to breathe in some particles, and from what I’ve read, repeated inhalation can irritate the lungs. I keep my face away from the beaker and flip on the fume hood if possible. Basic lab etiquette saves trouble, especially for your future self.

Clean Up and Storage Lessons

I picked up the value of tight storage from a spill that cost me half an afternoon. EDTA doesn’t belong in cracked bags or containers, since moisture will clump it or compromise the powder. Put it in a sealed, clearly labeled box, and keep it away from food and drinks. I’ve seen folks stuff chemicals on lunch shelves just to make space—nothing good has ever come from that.

Cleaning spills with dry paper towels just spreads the mess. I grab a damp cloth and work slowly, collecting powder without raising more dust. Waste goes in a marked bag for chemical disposal, not the regular trash. That short extra step keeps janitors and others from unwanted exposure.

Health Facts and Emergency Steps

Looks can deceive: EDTA disodium salt isn’t listed as highly toxic, but enough exposure causes harm. Irritated skin gets worse with repeated contact. Swallowing the powder can upset the stomach and, according to studies, mess with calcium in the blood if taken in big amounts. I keep the local poison control number posted by the door, though calling for help after accidental ingestion should always be immediate.

Fostering a Safety Culture

Old hands show newcomers the ropes, not by reciting rules, but by modeling habits every single time. I’ve seen this approach build safer workspaces than posters ever could. Respect for the risks grows out of regular talks, consistent gear, and a willingness to fix small problems before they become stories people regret sharing.

Safety with chemicals like EDTA disodium salt comes down to attention and repetition. Take the time to suit up, read the labels, and talk with your teammates. It’s one less worry at the end of the day, and, frankly, it lets everyone focus on the real work.

How should Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt be stored?

The Realities of Lab Storage

In any professional lab or even school science storeroom, nothing gets more overlooked than proper storage. Curious hands might reach for a bottle, someone else might rush to restock, and chaos starts right there on the shelf. With ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt—commonly called EDTA disodium—the really critical thing comes down to safety, stability, and keeping the powder potent for actual practical use.

Why Moisture Is the Enemy Here

Humidity in a chemistry storeroom sneaks up silently. EDTA disodium loves to soak up water from the air. Once moisture creeps in, you’re left with a clumpy mess that dissolves unevenly and can disrupt an experiment. Maybe in industry, minor degradation counts for little because everything is always on a massive scale. Personally, I’ve watched a careless cap or an unlabeled jar mess up hours of careful prep work—lesson learned the sticky way. For anyone who’s ever mixed a solution and found undissolved bits on the bottom of the flask, that old, mis-stored batch is usually to blame.

Containers and Their Big Role

Standard, clean, airtight containers matter more than any fancy storage “system.” Glass bottles with tight Teflon or polyethylene-lined lids seal best, keeping air and humidity out. Some go with high-quality plastic, and that’s fine for most lab use, as long as nobody reuses bottles with old labels—the number of times contamination has happened in rushed environments cannot be overstated. EDTA disodium doesn’t react with glass or most plastics, so the main thing is a tight, reliable seal. I’ve found jars with screw tops and moisture barriers built in work best, especially in labs near the coast or without climate control.

Location, Temperature, and Labeling Truths

Home for EDTA disodium should always be a cool, dry, shaded corner. Forget anything near radiators, sunny windowsills, or spots prone to wild temperature swings. Consistency in temperature preserves shelf life, so a dedicated cabinet or drawer—ideally away from acids or bases—keeps contamination risks down. Never underestimate the trouble caused by mislabeling and careless stacking. Clear, unambiguous labels with content, date, and hazard warnings guarantee the next person doesn’t fumble. Old habits die hard, but every time a bottle of EDTA disodium goes missing or turns up with mystery crumbs, someone pays the price in wasted materials or botched experiments.

Personal Experience and Safety Habits

Years in the lab taught me something about small details saving big headaches. Once, an entire class lost a week of results from careless storage—the salt had absorbed so much moisture it felt like dough. Ever since, every new bottle gets a tight seal and a spot well off the bench top—no exceptions. Gloves and eye protection make good sense, not because EDTA disodium is dangerous at first touch, but because routine prevents slip-ups. Spills, dust, and cross-contamination disappear fast if every tech and student sticks to proper storage. For busy teachers, just building a habit of monthly checks keeps all the bottles in fighting shape for work all semester.

Practical Steps That Hold Up

Anhydrous salts and powders last longer if protected. Simple silica gel packets inside storage cabinets help draw away stray moisture on humid days. For bulk storage, large drums work if kept in cool, clean, dry rooms with proper seals. On smaller scales, frequent inventory checks, replacement before expiry, and attention to how lids close make EDTA disodium a low-risk, reliable helper in chemistry and medicine. Most problems traced back to neglect, not complexity. That’s worth remembering every time a bottle comes off the shelf: real care in storage carries over to every result that follows.

What is the chemical formula of Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt?

Unpacking EDTA Disodium: What’s In the Name?

Understanding where things begin often means looking at their name. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt is a real mouthful, but most scientists just call it EDTA disodium. The mouthful has meaning, though. Inside that name hides a history of medical treatment, lab work, and some regular cleaning jobs. The basic chemical structure starts with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, which shows up in the chemical shorthand as C10H16N2O8. Toss in two sodium atoms, and you get the formula for the disodium salt: C10H14N2Na2O8.

Why The Specific Formula Actually Matters

The way those sodium atoms swap places with the hydrogens in the acid group changes a lot. Sodium helps the whole molecule dissolve much easier in water. A science teacher once showed me this in high school. We had an old bottle of pure EDTA (the acid form) and it refused to dissolve the way we needed it to. But the disodium salt? It went straight into solution and made the chemistry experiment work. That’s no small deal in labs, hospitals, or even home water treatment.

The difference goes past the surface. The molecular formula for EDTA disodium, C10H14N2Na2O8, doesn’t just mark its identity. It signals the number of ions it can wrangle out of a solution. This is the big trick scientists call “chelating.” They use EDTA disodium to trap metal ions like calcium, lead, and iron. In the lab, it clears away rogue metals that would disrupt reactions. In medicine, it helps remove toxic metals from the bloodstream. Drinking water systems use it to improve taste and safety. People might not see those molecules at work, but their health and results depend on that formula working as expected.

Why Quality and Expertise Matter

Research shows that improper use, low purity, or a swapped formula comes with risks. Residual sodium raises questions for people with dietary restrictions. If the chemical isn’t manufactured cleanly, contaminants can sneak in. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, along with the European Chemicals Agency, both issue strict guidelines for EDTA salts used in medicine or food. Pharmacies, hospitals, and even cosmetic companies who ignore these guidelines put their customers’ safety on the line. Reputable suppliers stick to rigorous standards, thorough lab testing, and third-party certifications to make sure what’s in the bottle matches what’s on the label.

Navigating the Fine Print: Solutions for Challenges

Problems can still crop up. People on sodium-restricted diets should consult a doctor before using supplements or treatments that include EDTA disodium. In my own family, someone with heart issues learned this the hard way after reading only the front of the bottle, not the ingredients.

Professionals can reduce dosing errors by verifying chemical labels twice—once after opening the bottle and once before mixing. Regulators can continue pushing for clear, readable labels. In the end, clear communication from chemists, manufacturers, and distributors forms the safety net. Sharing knowledge keeps people safe and ensures EDTA disodium gets the job done.

Is Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt soluble in water?

Understanding EDTA Disodium Salt

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt, often called EDTA disodium, pops up in a lot of products and lab settings. This compound grabs onto metal ions and keeps them in check. You see it in cleaning supplies, food preservation, and sometimes even in blood sample tubes at the doctor’s office. A big question that comes up all the time is about its relationship with water—does it dissolve, and why does that matter?

Solubility in Water

Yes, EDTA disodium salt dissolves in water. That’s a basic fact, but it’s also a big deal if you’ve ever come close to actual lab equipment or have watched someone try to make a solution. This salt breaks up pretty quickly in water, even at room temperature. In my time in the lab, tossing it into a beaker and giving it a swirl was all it took. No fancy tricks, just patience and a stir bar.

The numbers tell the same story: at room temperature, about 100 grams of this salt will dissolve in a liter of water. That rate puts it solidly in the “readily soluble” group. This also means you don’t need heated water just to get a clear mix, which saves time and fuss in fast-paced settings.

Why Solubility Matters

This solubility unlocks EDTA’s usefulness. Once it dissolves, it can latch onto just about any metal ion hanging around. This shows up clearly in water treatment or blood sample tubes where metals would mess up results or safety. If this salt clumped together or sat on the bottom, you’d run into big trouble trying to keep those metals in check.

Using a water-soluble compound saves steps for everyone. As someone who’s handled chemicals and mixed industrial batches, watching a powder settle at the bottom of a tank just eats up time and throws off precision. EDTA dissolves smoothly, cutting out headaches and guesswork.

Safety and Practical Use

You can’t talk about chemicals in water without thinking about safety. Once it’s dissolved, EDTA won’t float around as loose powder, which cuts down on dust risks. That matters in real rooms, not just labs. Even at home, people want cleaners they trust not to do weird things in solution.

Still, using water-soluble compounds comes with the responsibility of proper handling. EDTA grabs metal ions, which is great for cleaning, but also means it should go nowhere near natural waterways unless it’s part of a controlled process. In my experience, following disposal rules and keeping spill kits handy is basic good sense.

What Helps the Process

If you ever have trouble getting it all to dissolve, a little agitation goes a long way. Sometimes tap water brings in minerals that slow things down, so switching to distilled water fixes most issues. For bigger setups, magnetic stir bars make quick work of stubborn clumps.

There’s value in using water as a simple, reliable solvent. This makes EDTA disodium salt a handy tool for chemists, engineers, doctors, and regular folks looking for a safe way to keep metals from causing trouble.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Disodium 2,2',2'',2'''-(ethane-1,2-diyldinitrilo)tetraacetate |

| Other names |

EDTA disodium salt Disodium EDTA Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate Versene Dissolvine E-39 |

| Pronunciation | /ɛˌθaɪliːndiaˌmɪntɛtrəəsɪtɪk ˈæsɪd daɪˈsoʊdiəm sɔlt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | disodium 2-[2-[bis(carboxylatomethyl)amino]ethyl-(carboxylatomethyl)amino]acetate |

| Other names |

Disodium EDTA Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate Edetate disodium Disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate EDTA-Na2 Disodium EDTA salt EDETATE Disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ɛˌθaɪliːndəˌaɪəminˌtɛtrəəˈsiːtɪk ˈæsɪd daɪˈsoʊdiəm sɔːlt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 6381-92-6 |

| Beilstein Reference | 16925 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:61377 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1200294 |

| ChemSpider | 84715 |

| DrugBank | DB00974 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03dc07b6-fc44-4ac7-abaf-6321e19ca227 |

| EC Number | 200-573-9 |

| Gmelin Reference | 13721 |

| KEGG | C01353 |

| MeSH | D001972 |

| PubChem CID | 60932 |

| RTECS number | AH4375000 |

| UNII | 7T3S529W9J |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID9021398 |

| CAS Number | 139-33-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 17112 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:27377 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201123 |

| ChemSpider | 83613 |

| DrugBank | DB00974 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b4a8a7-cdc9-4818-935d-d5fca7ad058f |

| EC Number | 205-358-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 83367 |

| KEGG | D00043 |

| MeSH | D004938 |

| PubChem CID | 60932 |

| RTECS number | AH4375000 |

| UNII | 7O8FUX0V8I |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C10H14N2Na2O8 |

| Molar mass | 372.24 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.86 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -3.2 |

| Vapor pressure | <0.01 mmHg (20°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.0 (carboxyl), 2.7 (carboxyl), 6.2 (carboxyl), 10.3 (carboxyl) |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 6.16 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | χ = –39×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.570 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 7.49 D |

| Chemical formula | C10H14N2Na2O8 |

| Molar mass | 372.24 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 0.86 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 68 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.6 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.0, 2.7, 6.2, 10.3 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.16 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | χ = -39.0×10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.500 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 6.75 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 303.5 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -206.6 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 263 J/(mol·K) |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AB03 |

| ATC code | V03AB03 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS05, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS05,GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 355 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 2,800 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 2,800 mg/kg (Rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WH6650000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2.5 mg/m³ |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye irritation, may cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS08 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | > 527°C (981°F) |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 2,800 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 2,800 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | KWQ400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid Disodium Salt: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2.5 mg/m³ |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid EDTA tetrasodium salt EDTA dipotassium salt EDTA trisodium salt Calcium disodium EDTA |

| Related compounds |

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tetrasodium salt EDTA dipotassium salt EDTA calcium disodium salt EDTA trisodium salt |