DL-Tartaric Acid: A Closer Look at Its Science, Uses, and Future

Historical Development

Tartaric acid’s story reaches back centuries. Winemakers in ancient Greece and Rome already noticed a crystalline residue left behind in fermented grape juice. Science moved forward, and in the late 1700s, Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated tartaric acid, making the leap from artisanal curiosity to a recognized chemical. Work from French chemist Louis Pasteur in the 1800s showed that tartaric acid wasn’t just a single molecule, but could twist light in differing ways. Pasteur’s exploration of optical isomers changed chemistry forever. DL-Tartaric acid joined the family later, a racemic mixture—the same amounts of left- and right-handed molecules—partly thanks to growing demand for reliable acids in the food and chemical industries, and synthetic pathways that didn’t depend solely on wine byproducts. That historical change opened fresh doors, bringing its uses to more industries than winemaking alone ever offered.

Product Overview

DL-Tartaric acid shows up today as a white crystalline powder with a sharply sour taste, sandwiched firmly between specialty and commodity. Grape juice and fermentation aren’t its only sources; modern synthesis, usually from maleic acid or fumaric acid through chemical catalysis, allows steady, scalable supply. DL-Tartaric acid stands out for its precise sour bite, high solubility in water, and its growing role in sectors from baking and beverages to pharmaceuticals and industrial cleaning. It can slide into almost any process needing a non-toxic acid with stable properties. For people with allergies or religious restrictions, non-animal-based origins offer extra reassurance.

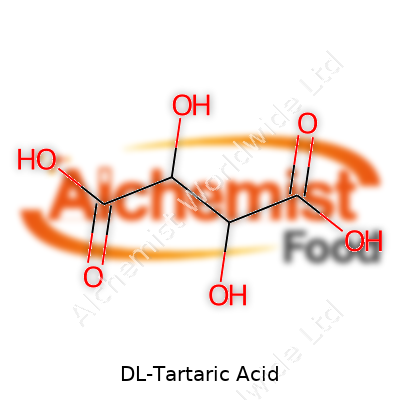

Physical & Chemical Properties

A glance at DL-Tartaric acid in the lab shows a melting point around 200°C with decomposition, strong solubility in water (about 139g per 100ml at 20°C), and moderate solubility in ethanol. Chemically, it’s a dicarboxylic acid (C4H6O6), containing two chiral centers—though as a racemic mix, it doesn’t rotate polarized light, defining one of its main differences from the L(+) or D(-) forms. DL-Tartaric acid remains stable in normal storage and doesn’t react aggressively toward most storage materials, although prolonged exposure to bases breaks it down. Its two acidic protons make it extremely versatile for chelating—binding calcium and magnesium ions—or creating buffer systems in labs and industry.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Companies supplying DL-Tartaric acid lay down clear technical specifications, focused on purity (expressed as percentage weight, with food or pharmaceutical grade often surpassing 99.5%), moisture content (usually less than 0.5%), and limits for heavy metals, arsenic, and other contaminants well below national regulations. Packaging and labeling follow rules spelled out by authorities like the Food Chemicals Codex, FDA, or European Food Safety Authority. Labels supply batch number, origin, shelf life, and handling precautions. Shipping labels often list the UN number for tartaric acid, ensuring transporters follow consistent safety practices. Conversation with QA officers at food or chemical plants always points to one thing—users double-check both technical data sheets and regulatory compliance before even letting a batch near their process lines.

Preparation Method

Older methods extracted tartaric acid from 'argol,' a sediment left in wine barrels, through filtration, precipitation, and crystallization. This process could never satisfy industrial-scale hunger or provide both left- and right-handed forms equally. Industrial chemists now start with petrochemicals. Maleic anhydride or fumaric acid act as the basic feedstocks, reacting with water and oxidants in carefully controlled steps. Once the dicarboxylic acid backbone forms, selective crystallization and purification techniques like activated carbon filtration or membrane separation bring up the purity. The resulting material shows no trace of grape compounds, pesticides, or wine allergens. Scaling up is a matter of reactor size and energy management, offering steadier costs and higher volumes. Some emerging biosynthetic pathways even use engineered microbes or fungi, pointing to greener production lines in the coming years.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Lab chemists value DL-Tartaric acid for its ability to act as a reducing agent in reactions such as Fehling’s or Benedict's test for sugars. Add a strong dehydrating agent, and the molecule loses water to form tartaric anhydride. React with bases, and get a set of versatile salts: potassium bitartrate—known well as “cream of tartar”—or sodium tartrate, which serves as a standard for Karl Fischer titration in water-content analysis. Esterification with methanol or ethanol turns it into tartrate esters, which find their way into cosmetics or pharmaceuticals. DL-Tartaric acid forms complexes with several metals, holding them in solution, which turns out practical in textile dyeing or photographic development. Sometimes researchers apply it directly as a chiral resolving agent, helping separate mirror-image drug molecules at an industrial scale.

Synonyms & Product Names

Chemistry textbooks and supply catalogs pile up alternate names for DL-Tartaric acid, each reflecting a different use or language of origin. These include Racemic acid, Butanedioic acid, 2,3-dihydroxy-, DL-, and E334 (as a regulated food additive number). Product codes or trade names sometimes feature in procurement departments, assigned by different producers around the world. Food industry labeling rarely uses the full chemical name, but emphasizes the E number or ‘Acidity Regulator.’ Drug firm catalogs—instead—will ask for “USP grade racemic tartaric acid” to ensure therapeutic compliance.

Safety & Operational Standards

Handling DL-Tartaric acid in large quantities demands a risk-based approach. Contact with eyes or open wounds burns, and repeated skin contact leads to irritation or rashes. Workers in high-dust environments wear gloves, goggles, and dust masks, enforced by material safety data sheets, OSHA rules, or EU directives. Industrial process engineers monitor air quality in packing or mixing zones, given tartaric acid’s well-known ability to release fine dust that lingers in the air. Precautionary equipment—eye-wash stations, safety showers, and good ventilation—become part of daily checks. Spills rarely trigger large-scale emergencies, as DL-Tartaric acid does not ignite directly and breaks down in the environment without generating lasting toxins, yet concentrated spills still get neutralized before cleanup. Waste disposal procedures send used water to pH-neutralization units before sewage treatment.

Application Area

In food, DL-Tartaric acid mostly helps balance flavor and pH in soft drinks, candies, jams, and effervescent powders. As a leavening acid in bakery recipes, it reacts with baking soda to make CO2 bubbles, keeping cake and bread textures light. It also tweaks wine taste, improves shelf life in processed fruit products, and holds metal ions away in chewing gum or oral care products. In pharmaceuticals, manufacturers add it to some effervescent tablets, syrups, and buffer mixtures. Metal processing industries use DL-Tartaric acid to clean surfaces, strip oxide layers, and stabilize plating baths. Textile dyers and tanners use tartrate salts for fixing colors. Lab scientists often reach for it in titrations, as a mild acid standard, and as a reagent for analytical chemistry.

Research & Development

Scientific teams keep probing new uses and better synthesis paths. A current hot spot explores biotechnology-based production routes. Using yeast or bacteria avoids petrochemical residues and lets the process run at lower energy, with less waste. In pharmaceuticals, new applications for chiral separation unlock safer, more effective drugs. Food technologists work on lower-calorie or sustainable acidulants using DL-Tartaric acid, aiming to keep clean-label foods both tasty and shelf-stable. Research on modifying tartrate esters leads into greener solvents and next-gen bioplastics. Studies also try pairing tartaric acid with dietary minerals, hoping to improve nutrient absorption or taste profiles in supplements. Each step taken by material scientists or process engineers slowly reshapes what's possible in both end uses and production methods.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists run exhaustive tests to check safety for both workers and end-users. DL-Tartaric acid passes most acute and chronic toxicity studies without raising serious hazards when ingested in the small doses seen in food or medicine. At high concentrations—well above normal consumer exposure—effects include mild gastrointestinal irritation or, in rare cases, cramping. Inhalation of concentrated dust causes respiratory discomfort, so responsible manufacturers maintain workplace air quality. No evidence shows DL-Tartaric acid causing cancer, reproductive toxicity, or gene-level damage, and global regulators have approved it for widespread food and pharma applications. Researchers still check long-term, low-dose exposures, looking for subtle metabolic or allergenic effects in sensitive populations. Animal studies back up the safety, but continued vigilance ensures emerging data receives fast attention before problems spread.

Future Prospects

Future demand for DL-Tartaric acid will likely trend upward, driven by expanding markets in functional foods, greener chemicals, and new pharmacological technologies. Advances in biosynthesis and recovery from agricultural waste promise lower carbon footprints and less reliance on oil-derived inputs. Food businesses scrape for every edge in taste and preservation, and new uses for acids and tartrate derivatives pop up every year. Regulatory scrutiny remains high, so producers investing in cleaner processes or allergen-free certifications gain a head start as export markets tighten standards. Pharmaceutical companies see tartaric acid as a key tool for chiral synthesis and new drug candidates, creating demand for higher-purity, more specifically tailored grades. Collaborative projects between industries might push tartaric acid into completely novel roles—in energy storage, biomaterial design, or even new environmental cleanup technologies.

What is DL-Tartaric Acid used for?

How DL-Tartaric Acid Shapes Food and Beverages

DL-Tartaric acid shows up in many places, but nowhere is it more visible than in food and drinks. Anyone who has enjoyed a bright, zesty wine has tasted a little help from this acid. As a winemaking ingredient, it helps control acidity, which matters for taste and shelf life. In the bakery, bakers count on it for leavening when mixed with baking soda, a trick dating back years. It gives biscuits and cakes that familiar rise and helps give whipped creams more staying power.

Its tangy flavor goes a long way. It finds its way into candies and soft drinks to deliver a sharper taste that sticks in the memory without overwhelming. Foods meant to last on grocery shelves rely on DL-Tartaric acid as a preservative, reducing spoilage from unwanted bacteria or fungi. Consumers see a better “best by” date, stores lose less to waste, and families spend less money on replacements. It’s a small ingredient making a big difference in how food tastes and lasts.

Use in Pharmaceuticals: A Helping Hand for Better Medicines

Outside of the kitchen, DL-Tartaric acid changes the game in medicine. Pharmaceutical companies need the right reactions to mix tablets or syrups, and this acid helps set the right environment. By balancing pH in formulations, it gives active ingredients a stable base. That means patients get medicine that works as promised from the first tablet to the very last. In chewable tablets, tartaric acid can mask bitter chemical flavors, making them easier for kids and adults alike to swallow. It feels small, but it creates better experiences for people who need regular medication.

Supporting Cleaning and Industrial Applications

In factories, DL-Tartaric acid lends a hand too. Its tart, slightly gritty texture becomes an asset for cleaning solutions, especially metal cleaners and rust removers. I’ve seen mechanics and jewelers alike reach for it, since it clears residue without damage. Construction sites and textile factories use it to adjust processes like dye-setting and tanning. Each time, it’s a safe, biodegradable choice that won’t leave troublesome residues behind.

Why DL-Tartaric Acid Matters for Sustainability

Many acids work in food, medicine, and industry, but some raise red flags for safety or environmental reasons. DL-Tartaric acid, sourced from natural byproducts like wine production, stands out for being non-toxic and breaking down without causing harm. Choosing this acid over harsher synthetic options can make a dent in chemical waste going into our waterways and air. Everyday choices like this add up when multiplied by millions of products on store shelves. It fits into the growing push for ingredients that do their job without an ugly side effect. Regulators and watchdog groups know this, which is why DL-Tartaric acid keeps showing up on “safe to use” lists worldwide.

Looking Forwards: Smarter Use and Better Practices

Businesses can tap into cleaner processes by picking ingredients like DL-Tartaric acid. Switching from old-school preservatives or harsh cleaners helps protect workers, consumers, and the land beneath us. On my own travels in food manufacturing, I’ve noticed that companies that embrace these smarter choices earn customer trust and face fewer recalls or safety issues. It might look like a simple white powder, but DL-Tartaric acid proves that the right ingredient can shape taste, health, and the planet’s well-being all at once. That makes it worth keeping in the spotlight as standards keep rising.

Is DL-Tartaric Acid safe for consumption?

DL-Tartaric Acid in Food and Drinks

I’ve seen tartaric acid on the back of candy wrappers, in grape juices, and even in some baking powders. DL-tartaric acid, a man-made version, often winds up in foods that carry a tangy kick. It helps with flavor, stabilizes baking, and stops color changes in jams and preserves. A lot of people eat foods with this ingredient without realizing it. You probably have, too.

Understanding the Difference: Natural vs. Synthetic

Tartaric acid shows up naturally in grapes, tamarinds, and bananas. DL-tartaric acid comes from labs, not fruit. Chemists combine two mirror-image molecules—d-tartaric and l-tartaric—into the synthetic version. Most countries don’t handle them the same way. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Food Safety Authority have each decided DL-tartaric acid is generally safe for food use, though they keep an eye on how much shows up in a day’s diet.

How the Body Handles DL-Tartaric Acid

Based on research, small amounts of tartaric acid move through the body without causing problems. The body flushes out what it doesn’t use. Problems usually appear when someone eats far too much. At very high doses, tartaric acid may bring on stomach pain or a bout of diarrhea. Too much of almost anything can have the same effect—think of eating a whole bag of sour candy. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives set an acceptable daily intake for tartaric acid and its salts at 0–30 mg per kilogram of body weight. For a person weighing 70 kg (about 154 pounds), that’s a lot more than anyone would ever eat in a day through regular foods.

Why Safety Matters

Processed foods use all kinds of acids and stabilizers. Every new synthetic ingredient deserves a careful look. Food safety rules exist for a reason—too many times, industries chased efficiency without pausing to think about health. I remember the fears surrounding some artificial sweeteners. That’s why oversight from scientific groups matters. They review animal and human studies, pore over toxicity data, watch for allergies, and track complaints from the real world.

Concerns and Misinformation

A few online forums lump DL-tartaric acid with more dangerous chemicals, or claim it causes gut problems. At regular serving sizes in food and drinks, there’s little evidence for those fears. Some folks raise questions about “synthetics versus naturals,” and I get it—what grows on a tree feels more trustworthy than something from a factory. In this case, the molecule acts the same way in the body, whether plucked from a grape or built in a lab.

How to Keep Food Additives Safe

Food companies bear responsibility here. Testing shouldn’t end once the ingredient lands on grocery store shelves. Tracking reactions, even rare ones, helps spot patterns. Regulators should keep testing new batches, keep tightening up intake limits if needed, and listen to medical professionals. If parents worry, they can limit ultra-processed foods and read ingredient lists. No single food additive replaces a balanced diet or fresh produce.

Looking Forward

As more synthetic additives enter the food world, every one deserves the same mix of watchfulness and common sense. DL-tartaric acid passes the standard safety checks for most people. If new research points to risks, regulators need to move fast, put limits in place, and let the public know—something I’ve watched happen in other cases. Until then, DL-tartaric acid sits in the same group as citric acid or malic acid: useful, safe in real-world amounts, and best eaten as part of food, not in pure form.

What is the difference between DL-Tartaric Acid and L-Tartaric Acid?

A Look at Tartaric Acid Types

Tartaric acid often shows up in wine, soft drinks, and baking powder. It’s the stuff that gives tang to grapes and keeps fizzy candy from falling flat. But there’s more beneath the surface. Two versions pop up all the time: DL-tartaric acid and L-tartaric acid. The letters and hyphens aren’t just chemistry jargon. I learned about their importance when my friend, a pastry chef, once ended up with a failed batch of meringue just because of the wrong tartaric acid.

The Science Behind the Letters

Nature has a way of arranging atoms in patterns. In the case of tartaric acid, there’s a mirror-image issue—think left and right hands. L-tartaric acid is the version found in grapes and most natural foods. The “L” hints at its alignment, or chirality, using an everyday word for a big scientific idea. DL-tartaric acid, on the other hand, mixes both left-handed (L-) and right-handed (D-) forms. This combination doesn’t show up in nature but is a product of manufacturing.

Real Effects in Food and Industry

At first, many would think both work the same. They don’t. If you add L-tartaric acid to a recipe, that’s what wine and candy makers expect. It gives just the right flavor and reaction. DL-tartaric acid, because of the mixture of forms, changes the way food tastes and behaves. In baking, L-tartaric acid keeps egg whites stable, which matters if you want that perfect rise. DL-tartaric acid, by contrast, often leads to disappointment—my friend’s meringue went flat and tasted off. Food companies avoid the DL version in consumer goods for this very reason.

Some industries use DL-tartaric acid because it’s cheaper to produce or science needs the combined form, but there’s a tradeoff. In pharmaceuticals, only the L-form matches biology’s natural composition. Our bodies recognize the L-shape and use it well. The DL mixture might be ignored by enzymes or do nothing at all. Over the years, I noticed supplement manufacturers always pick the L-form, showing they care about results.

Why Purity and Sourcing Matter

According to research studies, food and healthcare products rely on purity. Impurities or the wrong form sometimes lead to allergic reactions or poor outcomes. Europe and the US set strict rules on food additives. Both demand clear labeling, and companies need to tell buyers which form is in the product. Manufacturing plants use expensive tests to sort out L from DL material. Mixing them up leads not just to ruined cakes, but failed drug batches.

Better Choices through Educated Decisions

Anyone working with tartaric acid, from bakers to chemists, gets better outcomes by knowing these differences. Suppliers that prove the source and form of their tartaric acid turn out safer, better products. As a consumer, checking labels for “L-” or “DL-” helps make choices that fit health or recipe needs. For those who make things, sticking with natural sources or quality certifications pays off. This tiny detail—a letter and a hyphen—can affect flavor, effectiveness, and safety in ways that matter more than most folks realize.

How should DL-Tartaric Acid be stored?

Why Proper Storage Matters

DL-Tartaric acid goes into a surprising number of food and beverage products, along with various roles in pharmaceuticals and other industries. This powdery, white crystalline substance works as a stabilizer and preservative—functions that depend on it showing up at its best. It’s tempting to treat storage as a background concern, but one bad batch proves this approach just doesn’t fly.

Environmental Factors to Watch

Anyone who has stocked a storeroom knows how fast a high humidity day can ruin sensitive materials. DL-Tartaric acid draws moisture from the air, forming clumps or, worse, dissolving into a sticky mess. Excess moisture increases the risk of contamination and speeds up degradation. Handling a sticky barrel that should have poured easily is nobody’s idea of fun. Industry standards show a strong link between consistent product quality and storage environments with relative humidity below 50%. Keeping powders dry supports safe and effective use.

Direct sunlight also spells trouble. Although tartaric acid tolerates light better than some compounds, long-term exposure does more than fade a label. It opens the door to chemical changes and breakdowns, particularly when light exposure combines with heat. Find a spot away from windows, and business runs smoother.

Temperature swings bring another layer of risk. Many manufacturers recommend keeping DL-tartaric acid below 25°C. Hot storerooms have a way of accelerating chemical reactions. Constant high heat chips away at shelf life, makes the acid less reliable in recipes, and chips at operational budgets when stocks spoil prematurely.

Container Choices That Make a Difference

Not all packaging provides the same protection. The best results come from airtight, sealed containers made of high-density polyethylene or sturdy glass. Metal containers risk unwanted chemical reactions if the acid sits in contact with exposed metal surfaces. A friend at a small winery once learned this lesson after storing acids in unlabeled tins, leading to both confusion and waste. Good labeling and compatible packaging go hand in hand.

Moisture-absorbing packets or desiccants dropped into containers make a tangible impact, especially for people working in humid climates or older buildings with less climate control. These cheap additions help maintain the acid’s dry, free-flowing quality, even if the air outside the storeroom feels like a rainforest.

Handling and Safety Practices

Long sleeves, gloves, and masks do more than meet safety checklists—they protect skin and respiratory systems from irritation. Spills tend to happen during transport or weighing. Staff should use tools that minimize direct contact and keep lids tight between uses. Such habits require regular reminders, especially with shifting teams or new hires.

Labeling deserves respect. Clear, legible labeling limits mix-ups and helps prevent mistakes from snowballing into costly contamination events. Streams of unlabeled white powders in shared storage promise disaster; a bit of ink today saves headaches tomorrow.

Keeping Things Simple

DL-Tartaric acid isn’t some mystery ingredient, but it reacts to its environment like any finely milled powder. Clean, dry, cool storage in airtight, labeled containers should be the rule, not a suggestion. Routines and records help ensure that what’s measured out at the bench or kitchen sees the same conditions as the day it was delivered. Product consistency and safety depend on these steps, far more than most users realize.

What are the typical applications of DL-Tartaric Acid in the food industry?

Adding Tartness to Sweets and Drinks

Walk into any grocery store and pick up a bag of gummy candies or a bright powdered drink. There’s a good chance DL-tartaric acid played a part in building that sour tang most people either chase or shy away from. Confectionery producers use this ingredient to punch up fruit flavors and balance sweetness, creating a more refreshing taste. That zip attracts repeat buyers hoping for the right kick to each bite or sip.

Leavening Action in Baking

Many home bakers consider baking powder a pantry staple, but few realize that DL-tartaric acid helps make baking hundreds of cakes and muffins possible. It reacts with baking soda to create the bubbles that make cakes rise. By controlling those reactions, bakers consistently get fluffy textures and proper volume. Quality control depends on this process—no one wants to bite into a pancake that’s flat and dense.

Improving Quality in Wine and Juice

Wineries rely on tartaric acid to manage acidity and improve mouthfeel, especially when grapes don’t reach peak ripeness. By tweaking tartness, vintners ensure reds and whites taste crisp, not dull. Juice manufacturers often reach for the same trick, sharpening flavor profiles that customers expect from things like grape and apple juice. Without the right acid balance, drinks can taste off or go bad sooner.

Stabilizing Creams and Gelatin Mixes

Look at whipped cream or a brightly colored gelatin dessert. DL-tartaric acid keeps texture consistent and the finished product safe to eat for longer. This ingredient prevents sugar syrups from crystallizing and helps stabilize the air bubbles in whipped toppings. Reliability matters in food manufacturing where texture issues can ruin batches, cost money, and turn away loyal customers.

Color Fixing and Antioxidant Effects

Tartaric acid steps up where food color needs to stay bright, especially in processed fruits and jams. It slows down discoloration and keeps the product looking fresh all the way from the plant to the shelf. In some cases, it also acts as a mild antioxidant, reducing spoilage from exposure to air. These benefits help lower waste and give buyers the fresh look and taste they want.

Safe Sourcing and Quality Assurance

Food producers keep a close eye on ingredient quality and consumer safety, especially after several years of headlines about product recalls and contamination. DL-tartaric acid is made under strict food-grade guidelines, and suppliers furnish safety data as part of the standard process. Regular checks and certifications build trust between manufacturers and the public. Supervisors and lab technicians stay alert to any changes and work to maintain standards in every shipment.

Moving Toward Cleaner Labels

Growing demand for fewer and safer additives means even established products like tartaric acid get reviewed for safety and sourcing. Producers look for ways to use just enough—never more than regulations allow. Some switch to ingredients sourced from non-genetically modified grapes or natural fermentation. This signals a push in the food industry toward simple, clear labels, and more transparency about where ingredients come from.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,3-dihydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Other names |

DL-2,3-Dihydroxybutanedioic acid DL-Threaric acid 2,3-Dihydroxysuccinic acid |

| Pronunciation | /diː ɛl tɑːˈtærɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2,3-dihydroxybutanedioic acid |

| Other names |

Tartaric acid racemic Tartaric acid DL-2,3-Dihydroxysuccinic acid DL-Threaric acid DL-Weinsäure |

| Pronunciation | /diː-ɛl tɑːrˈtærɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 133-37-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 82620 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:32544 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1400 |

| ChemSpider | 54619 |

| DrugBank | DB09426 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 05b991b3-971a-4769-865f-96bd102a0168 |

| EC Number | 201-701-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 594 |

| KEGG | C01699 |

| MeSH | D02.241.511.562.875 |

| PubChem CID | 8768 |

| RTECS number | WS7925000 |

| UNII | W4888U641P |

| UN number | UN3265 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4020937 |

| CAS Number | 133-37-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1720541 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:43453 |

| ChEMBL | CHEBI:32162 |

| ChemSpider | 5126 |

| DrugBank | DB02576 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03f6c8a9-2b10-42d7-9b28-06e9dfee0167 |

| EC Number | 201-701-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 68194 |

| KEGG | C00793 |

| MeSH | D006349 |

| PubChem CID | 8768 |

| RTECS number | WW7875000 |

| UNII | AGG2FN16EV |

| UN number | UN 3265 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O6 |

| Molar mass | 150.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.76 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 139 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -1.0 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.98 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 3.32 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -5.21 x 10^-6 cm^3/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.59 |

| Dipole moment | 2.56 D |

| Chemical formula | C4H6O6 |

| Molar mass | 150.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.76 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 139 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.65 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.0 (first), 4.3 (second) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 3.22 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -2.44×10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.59 |

| Dipole moment | 2.53 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 155.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -951.1 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1341 kJ mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 159.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -925.2 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1341 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX06 |

| ATC code | A09AA02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a dry, cool, and well-ventilated place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Do not breathe dust or fumes. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-2-0-W |

| Flash point | 210 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 410 °C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 3320 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) Oral Rat: 493 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WX8400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 30 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | Up to 30 mg/m3 |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS labeling: Warning, H315, H319, H335 |

| Pictograms | GHS07, GHS05 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Precautionary statements: P264 Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P270 Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. P301+P312 IF SWALLOWED: Call a POISON CENTER or doctor/physician if you feel unwell. P330 Rinse mouth. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | NFPA 704: 2-0-0 |

| Flash point | 210 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 410°C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 3320 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) Oral (Rat): 4,900 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WW8575000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 30 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | <50 mg/kg (as tartaric acid) |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Maleic acid Fumaric acid Malic acid Succinic acid |

| Related compounds |

Maleic acid Fumaric acid Succinic acid Malic acid Oxalic acid |