DL-Methionine: A Deep Dive into Its Development, Uses, and Future

Historical Development

Methionine entered the spotlight through breakthroughs in protein chemistry during the early twentieth century. Researchers pursuing answers to why certain feed mixes left chickens stunted or sickly eventually zeroed in on methionine, an essential sulfur-containing amino acid that animals must get from what they eat. Early studies relied on extracting small amounts from plant and animal tissue. This process demanded both patience and buckets of raw material for a tiny sample. After World War II, synthetic chemistry took off. Scientists like Vincent du Vigneaud, famed for his Nobel-winning work on amino acids and sulfur biochemistry, set the stage for industrial production. Chemical companies saw an opportunity to support animal farming on a planetary scale, moving methionine out of academic papers and into sacks in feed mills. The introduction of a racemic mixture—DL-methionine—allowed for a more economical answer, giving rise to robust supply chains that still pulse today across North America, Europe, and Asia.

Product Overview

DL-Methionine comes as a white, slightly bitter powder, easily mixed into animal feed. It streamlines livestock nutrition, making sure poultry, pigs, and aquaculture species don't miss out on a building block that's tricky to source from grains and vegetable proteins alone. Chemical companies often standardize it at about 99% purity. Its use stretches beyond feed; pharma products, lab reagents, food supplements, or even as part of medical nutrition blends depend on it. The global production runs into hundreds of thousands of tons a year, reflecting its status as an industrial staple rather than a boutique chemical niche.

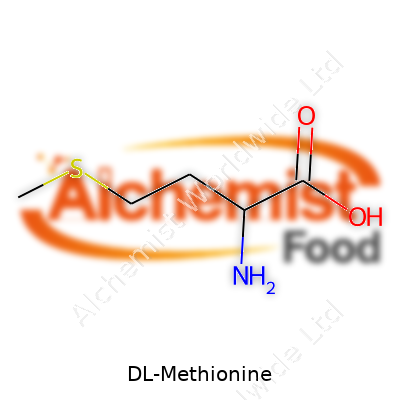

Physical & Chemical Properties

DL-Methionine carries the formula C5H11NO2S. Under a microscope, grains seem chalky; under the right light, there's a faint sheen. It melts at around 280°C with decomposition. Unlike some delicate amino acids, DL-methionine can take a bit of abuse—humidity, sunlight, or temperature swings during storage don't break it down quickly, especially in a sealed bag. Its moderate solubility in water ensures it blends reasonably well in solutions, which matters when large feed mills gulp hundreds of kilos into mixing tanks at once. The sulfur atom tucked inside gives off a subtle, earthy smell, a reminder of its role in protein biochemistry. On the technical level, the racemic mixture simply tosses the left and right-handed forms of the molecule into a single bag, since animals, especially poultry, metabolize both forms with similar efficiency.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Every shipment of DL-Methionine includes an assay for purity, usually above 98.5%. Moisture content rides below 0.5%. Analytical labs check for related substances—no need for a sack of feed-grade powder to contain impurities or degradation products. Labels keep it simple: content percentage, batch number, date of production, and, for many continents, compliance marks like the European Feed Additives Register or U.S. FDA Feed Additive Approval. Feed producers, veterinarians, and even animal owners find the lot information, storage guidelines, and country of origin stamped or stickered for traceability in case a feed recall ever makes the morning news.

Preparation Method

Factories produce DL-Methionine from acrolein, methyl mercaptan, and hydrogen cyanide. The core reaction routes through Strecker synthesis, first creating DL-methionine nitrile and then hydrolyzing it to the final product after working through intermediates. This chemistry has improved for sustainability and safety, with less waste and lower water use compared to postwar methods. Some producers invest in fermentation with genetically engineered microbes as an alternative, seeking a green label for customers worried about chemical footprints. Wherever produced, the final powder gets filtered, washed, and dried—sometimes granulated for dust control—before shipping out in bulk sacks that anchor the logistics of global animal nutrition.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

DL-Methionine shows a knack for subtle chemistry, trading its amino or carboxyl groups in peptide formation or jumping into redox reactions through its sulfur center. Methionine easily converts into S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which regulates methyl group donation in biology, or oxidizes to methionine sulfoxide under stress. Chemical research leans on these transformations to explore protein folding, enzyme catalysis, and mechanisms of oxidative damage—lending itself to studies far beyond the barnyard. For animal nutrition, modifications like creating hydroxy analogues—HMTBA, for example—let feed producers balance stability, digestibility, and absorption for specific livestock species.

Synonyms & Product Names

Most suppliers sell DL-Methionine under the straight chemical name. In scientific catalogs, you might see 2-amino-4-(methylthio)butanoic acid, or the shorthand DL-MET. Proprietary names turn up depending on the producer, with brands like MetAMINO (Evonik), Rhodimet (Adisseo), or Met-X (local companies). In academic papers, abbreviations like Me, Met, or DL-Met often keep writing concise, but in trade, DL-methionine dominates both packaging and paperwork.

Safety & Operational Standards

Anyone who has handled methionine on the loading dock or in a research lab knows it doesn’t rank as hazardous like caustics or solvents. Powder can irritate eyes or lungs if mishandled. Good ventilation, gloves, and dust masks keep warehouses and mixing rooms clear. Food safety standards demand strict tracking throughout production and storage. The material safety data sheet directs disposal away from water sources to avoid overloading streams with nutrients—a lesson learned as amino acid plants expanded into rural districts. Quality systems certified under GMP or ISO 22000 help steady the chain from drum to animal feed, guarding against contamination by metals, other amines, or spoilage microorganisms.

Application Area

Agriculture stands as the prime consumer, particularly in regions with dense animal production. Modern chickens and pigs can’t reach targeted growth rates on corn and soybean meal alone because they run short on sulfur amino acids. By adding DL-methionine, producers help animals build muscle efficiently, saving on expensive protein-rich ingredients and trimming both feed costs and environmental waste. Aquaculture operations find DL-methionine indispensable, since fish proteins often get replaced by soy or plant meals to protect ocean stocks. Pet food makers use it in both kibble and canned diets, especially for cats, which need more methionine than dogs. Beyond animal feed, pharmaceuticals rely on methionine for intravenous nutrition or as a supplement during chemotherapy. Research regimes testing methylation, detoxification, or oxidative damage run on methionine and its derivatives. A niche segment even flows to cosmetics, promising improved skin resilience by boosting the biochemistry that handles oxidative stress.

Research & Development

Much of today’s work digs into improving both the yield and eco-friendliness of DL-methionine production. Synthetic biology teams engineer bacteria and yeast to coax more methionine from sugars instead of oil-based chemicals, betting on a future when every feed ingredient answers to carbon accounting. Nutritionists around the world cross grains, measure amino acid digestibility, and trial new blends to stretch protein sources and relieve cost spikes or supply chain squeezes. Academia explores methionine’s roles in aging, epigenetics, and chronic disease by mapping how its breakdown shapes cell fate or inflammation. Companies support studies up and down the supply chain, chasing tweaks that could lower feed conversion ratios or slash nitrogen excretion by a few precious percent—small gains that scale to millions of tons of grain.

Toxicity Research

Extensive animal studies show that methionine’s safety hinges on balance. Too little leaves animals weak, sick, or stunted. Doses far beyond necessity, over weeks or months, put strain on the kidneys and may produce excess methylation, shifting metabolism in unintended ways. For common usage in feeds, safety margins prove wide and reassuring. In humans, rare metabolic conditions such as homocystinuria block methionine breakdown, forcing strict dietary control. Toxicology panels routinely test for chronic and acute exposure, reporting that standard handling, ingestion, or inhalation under feed mill conditions stays well below any even theoretical risk threshold. Regulations in Europe, North America, and Asia demand continuous re-examination—an approach that keeps the safety profile up to date with new production technologies or routes of exposure as industries evolve.

Future Prospects

The years ahead hold both challenge and promise for DL-methionine. As livestock production grows, so does scrutiny of agricultural footprints—methionine will anchor conversations about efficient protein production, sustainable aquafeed, and the role of supplements in vegan or flexitarian pet foods. Producers keep an eye on fermentation, biocatalysis, and low-energy synthesis, hoping to deliver methionine using fewer fossil ingredients and leaving less waste behind. Nutrition science may well discover new roles in health, medicine, and biomaterials, prompted by deeper understanding of methylation and oxidative stress. Oversight agencies and environmental advocates have a stake in monitoring runoff, trace impurities, and greenhouse gases, raising questions that need good science and steady transparency. For every pig farm or poultry complex feeding DL-methionine, the trade-off between animal growth, feed cost, and planetary health grows starker—and finding the best path forward invites innovation, rigorous study, and practical stewardship from every corner of the industry.

What is DL-Methionine and what is it used for?

Understanding DL-Methionine

Standing in a feed mill, you’d recognize the smell—slightly sharp and unmistakably synthetic. DL-Methionine isn’t a word most people use daily, but it plays a massive role behind the scenes in food production. It’s a synthesized amino acid, used mostly for livestock and poultry. Chickens eat it. Piglets need it. Fish farms bank on it. Even though methionine shows up in natural feedstuffs, corn and soybean meal rarely have enough. Without a supplement, animals just don’t grow or thrive the way farmers expect.

Why Nutrition Hits the Limit Without It

Chickens can’t make methionine on their own and neither can pigs. Every cell relies on it to build protein, and that stretches beyond muscle—think about feathers, skin, immune cells. At farms I’ve visited, birds lacking methionine lose feathers, seem listless, and can’t convert feed into growth. Feed manufacturers figured out long ago that blending a pure form into rations gives a predictable, high-quality result. There’s less waste, and animals grow strong. The added efficiency cuts down on land and water costs, too—less wasted protein going in, more healthy product coming out.

Safety and Regulation

Folks often ask if synthetic amino acids cause trouble for health or the environment. As someone who’s dug into FDA and EFSA reports, I’ve seen the numbers: DL-Methionine breaks down into the same natural components animals expect. No mystery ingredients. Regulators around the globe have studied feed-grade methionine for years. Proper use lines up with established animal health standards. Like most feed additives, trouble pops up only when someone ignores mixing directions or piles on too much.

Industry Realities and Animal Welfare

Price swings shake up feed markets. Sometimes synthetic methionine costs more. Reliable supply chains matter. I’ve watched feed mills scramble when markets go haywire, but no real substitute matches the consistency and cost-effectiveness of a supplement. Grain and soybeans alone force producers to use more raw protein, driving up cost and putting more strain on resources. With DL-Methionine in the mix, it becomes possible to dial back excess protein. That improves animal comfort, reduces nitrogen runoff, and keeps consumer concerns at bay around livestock waste.

New Research and Sustainability

There’s a growing push to balance animal efficiency with sustainability. Recent research looks at microencapsulated forms, slow-release techniques, and precision feeding. I’ve sat through producer meetings where experts challenge folks to trim back over-supplementation, monitor environmental impact, and align nutrition with the lifecycle needs of animals. Advances in feed technology promise more accurate mixing and smarter delivery, helping to stretch resources and shrink the environmental footprint. The key lies in knowledge and cooperation between nutritionists, veterinarians, and farmers.

Potential Paths Forward

Education—on the farm and online—makes a difference. Feed companies offer training on safe handling, precision mixing, and regular monitoring. Advocating for transparency helps maintain trust throughout the food chain, from protein producer to grocery store shelf. I’ve learned from experience that simple improvements—better bin management, tighter quality checks—pay off. Collaborating across sectors will keep livestock nutrition strong, animal health stable, and food production sustainable.

Is DL-Methionine safe for animals and humans?

Clearing Up What DL-Methionine Is

Methionine matters in both animal feed and human diets. The “DL” version is a synthetic amino acid that mixes two forms: D-methionine and L-methionine. Animals can turn both into useful building blocks for growth and protein creation. In livestock and poultry, DL-methionine has helped bring better growth results and tighter feed efficiency. For humans, methionine is essential, though most get enough from a regular diet.

Safety Research and the Real World

Plenty of studies look at whether adding DL-methionine to animal diets does any harm. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the FDA have both said it’s safe at levels used on farms today. No evidence links this amino acid to cancer, birth defects, or toxic buildup in livestock. I’ve talked to vets and farmers who see the proof in healthier animals—stronger fur in pets, better egg and milk yield in farms, and less waste from feed.

Short-term and long-term feeding trials back this up. Chickens, pigs, fish, and even cats digest and use DL-methionine without trouble. Overdosing rarely causes issues, and only at levels far beyond what producers use. Nutritionists do caution that animals need balance. Even water can do damage if overconsumed—methionine is no exception.

On the human side, methionine forms part of the story for many supplements. DL-methionine goes into some over-the-counter formulations, aimed at kidney health or to acidify urine. Clinical guidance says short-term use carries little risk for most adults, though people with certain genetic or metabolic conditions stick to doctor’s orders. Researchers warn against mega-dosing, as too much methionine can push up homocysteine levels, raising risk for heart disease. Public health guidelines around amino acid supplements keep that in check.

The Role of Quality and Transparency

What remains critical is purity in the product and following clear dosing. I’ve seen cases where poor-quality feed supplements turn up with impurities, driving health concerns much bigger than methionine itself. Reputable companies stick to good manufacturing practices, and governments run spot checks to keep unsafe products away from the dinner table.

On labels for both feed and supplements, consumers deserve clarity. It helps vets, nutritionists, and everyday people make choices with confidence. Real-world stories underscore the importance of trust: a goat farmer avoids losses when his feed supplier guarantees consistent methionine levels; a pet owner sees the benefits in a healthier, shinier coat on their rescue dog. The safety record stays strong, barring a lapse in honesty or oversight somewhere in the chain.

What Could Improve

Science keeps moving. Improved genetic testing can spot which animals might react differently to specific diets. Smarter, tailored feeding strategies lower the odds of giving too much. For human supplements, clearer education about risks and benefits would help those without medical backgrounds steer clear of accidental overdosing. Regulators could cut through jargon, using plain language when explaining safety margins.

Farmers, healthcare workers, and families all benefit from simple, straightforward communication. DL-methionine has become a trustable tool, but it’s still up to people at every step—from factory to feed trough to dinner plate—to use knowledge, common sense, and the best science available.

What is the recommended dosage of DL-Methionine?

DL-Methionine: Not Just Another Supplement

DL-Methionine finds its way into animal feeds everywhere. Poultry growers, pig farmers, and aquaculture operators look to this amino acid for good reason. Birds and livestock can’t build their own methionine, so it must come through feed. Without enough, growth stalls, feathers lose shine, and heavier issues follow. On the flipside, too much leads to wasted money and can strain the animal’s health. Pinning down the right dosage makes all the difference.

Dosage: What Do the Experts Recommend?

Recommendations for DL-Methionine rely on research and decades of field experience. In poultry, feed formulas usually call for around 0.3% to 0.5% methionine in the total diet, with the precise value tied to growth stage, breed, and feed composition. For broilers, young chicks need higher levels since their bodies develop fast. After the early weeks, methionine dips a bit as growth rate slows. Laying hens require steady supplementation to keep egg production and shell quality consistent. Numbers tend to range from 0.28% to 0.32% for layers.

Pig nutrition brings its own needs. Starter pigs, especially those under stress from weaning, take in 0.3% to 0.35%. Growth and finishing pigs do well with 0.25% to 0.35%. Dairy cows aren’t as sensitive to DL-Methionine levels, but those fed high-corn diets benefit from balancing amino acid profiles, often at rates near 0.08% to 0.1% of dry matter intake. Fish farming circles rely on feed blends containing up to 0.6% for some fast-growing species.

Actually Getting Dosage Right

Farmers know a good deal about the animals they care for, but dosages aren’t always a matter of experience alone. Feed makers run lab tests to determine methionine already present in main ingredients like corn, soy, and wheat. Since natural feed can’t deliver total needs, companies top up synthesized DL-Methionine. Not all feeds use the same grain mix, so dosage adjustments from one operation to the next make a big difference.

Beyond growth, the right dose improves feed efficiency, meaning animals gain more weight or produce more eggs without extra feed input. Keeping methionine at the right level also cuts nitrogen waste because the body uses what it needs without shedding as much unprocessed protein into manure. This kind of practical benefit hits home on family farms and large commercial operations. The environment thanks the process, too.

Risks of Getting Dosage Wrong

Packing in more DL-Methionine than needed doesn’t give extra results. Amino acid imbalance can slow growth and cost dollars in wasted supplement. In rare cases, over-supplementation leads to health risks, like kidney strain or metabolic issues. Not enough turns up as poor growth, feather loss, and weaker immune response. The margin for error leaves little room for guesswork. Regular feed analysis, solid formulation, and sometimes even consulting animal nutritionists keep everything on track.

My Experience with Adjusting Feeds

Growing up around small-scale poultry and livestock farms, I saw firsthand what happens when feed formulas miss the mark. My neighbor’s broiler flock once showed patchy feathers and slower growth after a batch of new feed left out key amino acids, including methionine. Fixing the formula, with the right DL-Methionine added at the rates recommended above, turned things around within weeks. Feed costs balanced out too, because birds grew faster and healthier, bringing more reliable returns.

Regularly checking nutrition labels, consulting with feed reps, and taking time to watch animal health saves money and delivers real benefits. Letting the science guide decisions about DL-Methionine dosage beats chasing trends or cutting corners. Right dosing supports animal well-being, keeps operations sustainable, and lines up with the best practices recommended by feed experts across the globe.

Are there any side effects or precautions when using DL-Methionine?

DL-Methionine—Why Even Talk About Side Effects?

Many farmers and pet owners grab DL-methionine to round out animal diets, especially since feed sometimes lacks enough methionine. This amino acid helps boost growth, supports healthy skin and feathers, and keeps the liver ticking. No surprise, then, that nutrition experts recommend it, especially in poultry and pig feed. But one thing often overlooked is the question about what could go wrong if we get the dose or product mix-up.

What Happens with Too Much DL-Methionine?

The phrase “more isn’t always better” applies here. Give animals too much and you can set them up for a rough ride. Some reports point out that overdose leads to decreased growth, odd posture, and less feed intake. In my days on a family farm, I saw firsthand how pigs pulled away from feed if supplements got too strong—a natural reaction to something feeling off. Birds sometimes lost their coordination, which felt unsettling to watch.

Veterinary studies have found that overdosing—especially with young animals—brings on metabolic problems, heart risks, or even acidosis. Feed companies walk a fine line: too little doesn’t help, and too much can trigger side effects or waste money.

The Subtle Risks: Not All Precautions Are Obvious

Aside from overdose, poor blending or inconsistent measuring sets the stage for health problems. Commercial feeds sometimes show hotspots—one part packed with methionine, another part barely laced at all. Here is where regular sampling and quality control make all the difference. Feed mills with a good reputation almost always invest in precise scales and solid staff training. Without that, animals may develop deficiencies or end up stressed by sudden spikes.

Some breeds are more sensitive. Specialty chicken breeds and certain dog lines don’t handle fluctuations well. Sulfur-containing amino acids like methionine also interact with other nutrients, so mixing supplements without expert advice can mess up zinc or copper levels.

Handling in the Workplace: Human Safety Matters Too

Feed staff sometimes overlook their own health in a hurry to boost production. Breathing in DL-methionine dust can irritate the respiratory tract. Gloves help, but decent air circulation and basic face masks make a bigger difference, especially in tight feed rooms. A simple hand-washing routine cuts down on skin irritation. One feed technician I met ended up with red, dry hands until the team switched to using protective cream before and after each shift. No fancy science, just good habits—and it worked.

Making Smart Decisions: A Path Forward

Reading the label and keeping to tried-and-true feeding rates lays the foundation for success. Tracking animals for a week after changing the formula often gives early warning if something’s amiss. For new users, a vet consultation never hurts—most vets recommend a review if someone plans to tweak feed routines or introduces supplements. Feed manufacturers who open their doors to QA audits not only protect animals but also win loyal buyers.

In the end, putting animal and handler well-being first pays off for everyone. DL-methionine brings value, no doubt, but it demands respect and attention to detail to keep livestock and people safe and productive.

How should DL-Methionine be stored and handled?

Reliable Stewardship in Animal Nutrition

DL-Methionine plays a vital role in feed formulation, supporting healthy animal growth and improving production rates. More folks in agriculture and feed plants are relying on synthetic methionine. This means keeping it safe, stable, and fully effective from delivery right through to use gives everyone a better shot at predictable results.

Facing the Real-World Risks

DL-Methionine comes as a white, crystalline powder that’s both stable and surprisingly sensitive to certain conditions. Moisture stands out as its main threat. Grain dust, humidity in processing areas, and even brief exposure to steamy air during unloading can cause caking, clumping, and make it hard to mix. Water can trigger degradation, knocking down its nutritional value and causing production headaches.

Heat brings its own set of worries. Keeping large volumes in poorly ventilated rooms, letting containers sit near boilers, or stacking bags where sunlight creeps in can cause the powder to break down or discolor. Along with losses in effectiveness, these changes make it harder to spot genuine quality issues.

Direct sunlight not only warms the storage area but also speeds up chemical changes, limiting shelf life and risking spoilage before it reaches the feed line.

Using Tough Gear for Tough Jobs

Heavy-duty, sealable containers keep DL-Methionine dry and away from air. In my time spent on feed mill floors, you can spot the difference between well-stored product and the kind left open and exposed. Bags that feel soft or stick together speak volumes about poor handling. High-density plastic or lined fiber drums shut tight after every use put an end to curious rodents and water leaks. Larger warehouses often install pallets so nothing rests directly on damp floors.

Handling routines matter, too. Simple steps — like goggles and dust masks — keep workers safe and the material uncontaminated. Scoops and shovels cleaned regularly block the carryover of other feed materials. Team members stay healthier, and mixing batches run true to formula.

Logistics tells the rest of the story. DL-Methionine does not travel with strong-smelling items like fishmeal, fertilizers, or volatile chemicals. Isolated storage, away from pesticides and feed acids, makes it easier to prevent accidental contamination.

Clear Rotation and Up-To-Date Training

Every year brings new staff into the business. No matter how experienced the last crew was, each person handling DL-Methionine gets a rundown on site protocols — from storage temperatures to spill management. Labelling bags by date gives full traceability, shrinking waste by letting staff use older stock first.

Keeping Safety and Quality in Focus

One slip with methionine means lost feed quality, spoiled batches, and extra labor to clean up the fallout. Some facilities use temperature and humidity sensors to keep a close eye on their environment. Written rules work only if everyone follows them, so leadership helps by modeling care and discipline at every turn.

Good storage and handling practices don’t call for fancy gadgets or high-tech solutions. A well-ventilated, dry area and a team that pays attention are all it takes to get the most value out of every bag.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Amino-4-(methylsulfanyl)butanoic acid |

| Other names |

2-Amino-4-(methylthio)butanoic acid Methionine, DL-form DL-2-Amino-4-(methylthio)butyric acid |

| Pronunciation | /diː ɛl mɛˈθaɪəˌniːn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-amino-4-(methylsulfanyl)butanoic acid |

| Other names |

DL-2-Amino-4-(methylthio)butyric acid DL-Met Methionine DL-form DL-Methionin |

| Pronunciation | /ˌdiːˌɛl.məˈθaɪ.əˌniːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 59-51-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 17112 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16643 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL42938 |

| ChemSpider | 41086 |

| DrugBank | DB00132 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 06c401ad-5d3a-4dcb-9c3d-70bce437d8b2 |

| EC Number | 2.3.1.13 |

| Gmelin Reference | 74036 |

| KEGG | C00073 |

| MeSH | D002585 |

| PubChem CID | 6137 |

| RTECS number | OP5650000 |

| UNII | 605C3I1B8B |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5023321 |

| CAS Number | 59-51-8 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1811072 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:16643 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL418833 |

| ChemSpider | 17001 |

| DrugBank | DB00132 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.878 |

| EC Number | 2.3.1.13 |

| Gmelin Reference | 13611 |

| KEGG | C00170 |

| MeSH | D03.438.221.173 |

| PubChem CID | 6137 |

| RTECS number | OP8756000 |

| UNII | 590Y4FDV9H |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C5H11NO2S |

| Molar mass | 149.21 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or pale gray crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.6-0.7 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | soluble in water |

| log P | -2.1 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 2.28 (carboxyl), 9.21 (amino) |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 10.0 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -7.9e-10 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.521 |

| Dipole moment | 5.14 D |

| Chemical formula | C5H11NO2S |

| Molar mass | 149.21 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or light grey crystalline powder |

| Odor | Slightly sweet odor |

| Density | 0.6 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | slightly soluble |

| log P | -2.14 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa = 2.28 (carboxyl), 9.21 (amino) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 5.74 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.521 |

| Dipole moment | 4.04 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 53.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -234.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3235 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 101.1 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -234.5 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3221 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA02 |

| ATC code | A16AA11 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May be harmful if swallowed, inhaled, or absorbed through skin; may cause respiratory and skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319, Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Precautionary statements | IF IN EYES: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. If eye irritation persists: Get medical advice/attention. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-1-0 |

| Flash point | Flash point: >100°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 385°C |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 5,620 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Rat oral 5,600 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | S947 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.3% |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a dry, cool, and well-ventilated place. Avoid dust formation. Avoid breathing dust. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use personal protective equipment as required. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 3-1-0 |

| Flash point | > 230 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 470 °C |

| Explosive limits | Lower: 3.3 vol% Upper: 19 vol% |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 5,600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 5,620 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | SR1050000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 15 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 0.2 – 0.5% |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Methionine L-Methionine D-Methionine Methionine sulfoximine Homocysteine Cystathionine |

| Related compounds |

Methionine sulfoximine Ethionine S-Adenosyl methionine |