DL-Alanine: Tracing Its Journey, Uses, and the Road Ahead

Historical Development

DL-Alanine caught scientists’ eyes long before it earned its spot in labs and industries. As early as the 19th century, biochemists explored the simple amino acids tucked inside proteins. Racemic alanine, or DL-alanine, intrigued many early researchers, not just for its structure but for its potential to reveal secrets about protein synthesis and metabolism. Synthetic chemistry grew hand in hand with biochemistry, and methods for creating DL-alanine from simpler starting materials opened the floodgates for large-scale production. Early days involved laborious extraction from silk fibroin and casein, but as synthetic routes improved, the racemic mix of D- and L-alanine found its way beyond academic shelves and into diverse fields such as food additives and pharmaceuticals.

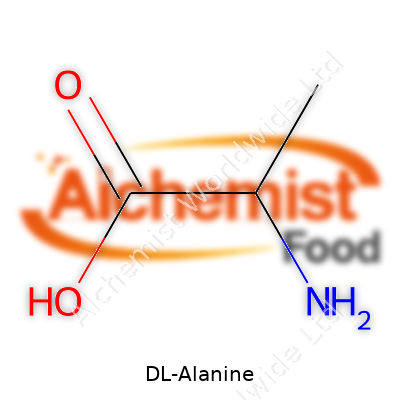

Product Overview

DL-Alanine delivers both D and L enantiomers, so it steps into functions that go beyond what the naturally occurring L-form manages within the body. By combining both forms, chemists gain a compound with distinct uses in biochemical research, industry formulations, and specialized diets. It appears as a white, odorless, crystalline powder that blends well in aqueous environments, a trait valued by those producing nutritional supplements and infusion fluids. As a non-essential amino acid, alanine plays supporting roles—its synthetic blend broadens applications, working quietly in the background across many products most consumers never think about.

Physical & Chemical Properties

DL-Alanine shows up as a stable, crystalline solid, dissolving easily in water but less so in ethanol. It resists heat, holding shape well up to around 297°C before breaking down. Its melting point hovers around 297°C, and a pH-neutral aqueous solution adds appeal for both medical and industrial applications. Comprising C3H7NO2, each molecule holds a simple methyl side chain that offers limited steric hindrance, making it easy to work with in both lab experiments and commercial settings. The racemic mixture keeps both enantiomers at parity, sidestepping the stereochemical selectivity that sometimes limits application options.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Reputable suppliers specify purity by weight—commonly >98%—with loss on drying, residue on ignition, and heavy metals all rigorously monitored. Labels usually list the compound’s name, batch number, molecular formula, and expiration or retest date. Transparency helps customers assess compatibility with their needs. In healthcare, regulatory guidance points to clear demarcation between food, feed, and API-grade lots. Product traceability underpins confidence, especially since DL-alanine ends up in products influencing health and nutrition.

Preparation Method

Commercial production rarely leans on extraction from natural sources. Most DL-alanine comes from Strecker synthesis, starting with acetaldehyde, ammonium chloride, and potassium cyanide. This reaction forms an aminonitrile, hydrolyzed later to deliver the racemic amino acid. Efficiency matters for scale, and over the years, companies fine-tuned yields, safety, and cost. Fermentation or enzymatic approaches turn up sometimes in biotechnological operations, but chemical synthesis remains king due to consistency and cost benefits. Some industrial producers tout “green chemistry” adaptations, minimizing hazardous byproducts and solvent waste where possible, guided both by regulations and profit margins.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

DL-Alanine’s amine and carboxylic acid groups spark various reactions—enzymatic deamination, condensation for peptide formation, and esterification for analytical standards. Chemists sometimes tweak the methyl group for tailored activity, especially in pharmaceuticals. In protein engineering, derivatives of alanine prove essential as site markers, replacing more reactive residues to “silence” an active site or to study structural context. Researchers use modifications to control solubility, create prodrugs, or improve uptake in cell culture applications.

Synonyms & Product Names

Across catalogues and regulatory documents, DL-alanine also appears as Racemic Alanine, α-Alanine, or 2-Aminopropanoic Acid. These names reflect its dual enantiomeric identity and basic structural features recognized across international guidelines and academic publications. Some suppliers might refer to it under food additive numbers for clarity in ingredient lists.

Safety & Operational Standards

Decades of use place DL-alanine among the lower-risk amino acids for normal handling. Workers focus on preventing dust inhalation and long-term dermal contact, so masks and gloves remain standard in production areas. Food and pharma applications demand compliance with relevant ISO and GMP protocols. Regulatory checks for contaminants—think heavy metals and microbial loads—protect not just workers but end users. Environmental rules steer waste handling, especially since legacy manufacturing used harsher reagents than today’s more sustainable routes.

Application Area

Pharmaceutical makers value DL-alanine in infusion solutions and as a stable substrate for enzyme assays. Food companies add it for both taste modification and as an ingredient in amino acid blends. In microbiology, its racemic character sets it apart—certain microorganisms respond differently to D- and L-forms, giving researchers tools for selective culture or metabolic pathway tracing. Veterinary supply has carved out a regular place for DL-alanine, especially as a supplement supporting animal growth and gut function. Specialty chemistry labs reach for DL-alanine when they want a stable reference or non-chiral background in reaction setups.

Research & Development

Research into metabolic disorders and enzyme specificity draws heavily on DL-alanine as a tool. Its ready availability at high purity lets investigators parse the roles of D- versus L-amino acids in cell function and disease. In protein design, swapping in alanine—known as alanine scanning—lets researchers probe the influence of side chains in folding and binding. Some projects target the design of new drugs or bio-based materials that hinge on alanine’s metabolic flexibility. Across biotech, efforts continue to use recombinant processes to craft DL-alanine with even lower environmental impact.

Toxicity Research

Animal studies and acute human exposures outline a favorable safety profile. Normal dietary levels produce no adverse effects, given alanine’s widespread natural presence and metabolic roles. Massive overdoses, intentionally rare in real-world use, can impact renal function or disrupt amino acid balance, but regulatory bodies note that conventional applications remain within safe boundaries. Researchers keep an eye on possible long-term risks when D-enantiomer buildup skews normal metabolism, particularly in rare metabolic conditions, though typical exposures show low risk for causing toxicity.

Future Prospects

The horizon for DL-alanine shines brightest at the intersection of sustainability and synthetic biology. Industrial chemistry and biotechnology both compete to lower energy inputs and waste, nudging processes away from hazardous reagents and toward fermentative production. In medicine, the deeper understanding of D-amino acids in disease opens new roles for racemic alanine compounds as diagnostic tools or adjunct therapies. As landscapes shift in regulation and consumer expectation, the drive to deliver both high-purity and environmentally responsible DL-alanine intensifies. So far, science and market pull match stride, promising that the story of this simple amino acid remains far from over.

What is DL-Alanine used for?

Understanding What DL-Alanine Actually Is

DL-Alanine is a synthetic amino acid. It comes as a white, crystalline powder and stands as both a building block in protein and a supplement in the lab. Scientists refer to the “DL” part because the molecule contains both D- and L-forms, which mirror each other. Most animals, including us, use the L-form to build proteins in the body. The combined form, though, pops up across various industries for reasons beyond basic metabolism.

Food Science Gets a Helping Hand

Food companies rely on DL-Alanine as a flavor enhancer and stabilizer. Its mild, slightly sweet taste can soften harsh chemical edges in low-calorie sweeteners. I first read about it as a safety buffer in processed foods—think keeping shelf-stable soup and powdered sauces safe and palatable. With consumers caring about what sneaks into their food, it's good that DL-Alanine already shows a strong safety record according to international food safety authorities.

DL-Alanine Turns Up in Exercise Supplements

Athletes sometimes look for “beta-alanine” on supplement shelves for better performance, but DL-Alanine appears in some powdered blends to boost amino acid content. Since both forms break down to vital metabolic fuels, they act as backup sources when energy dips, especially under heavy physical stress. Research out of Japan and Europe points to its role in muscle endurance and recovery. If you're on a high-intensity training program, you might notice your supplement facts panel listing an “alanine” blend.

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Research

Medical researchers value DL-Alanine because it’s easy to track in metabolic studies. It helps in measuring kidney and liver function in lab tests. Since the body quickly absorbs and uses alanine, it becomes a safe marker for many diagnostic exams. Biologists who tinker with cell cultures often mix DL-Alanine into their growth media because it ensures even simple organisms can build up essential proteins.

Industrial Uses: Not Just for People

DL-Alanine has a surprising role in producing certain biodegradable plastics. Manufacturers use it as a precursor in green chemistry for items that need to break down safely in the environment. There’s something oddly satisfying about seeing an amino acid leave the lab bench and end up improving industrial processes.

Looking Towards Safer and Smarter Use

Trust matters. Regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration check synthetic amino acids for contaminants and dosing standards. For folks considering food or fitness supplement blends with DL-Alanine, pay attention to labeling and origin. Fake supplements can slip into the market, especially online, without enough quality checks.

The biggest takeaway is to rely only on transparent brands with clear sourcing. In a world flooded with complicated ingredient lists, a little knowledge goes a long way. DL-Alanine, for all its chemistry, fits small but important needs across food, medicine, and industry. Its story shows what happens when our basic molecules get a smart, safe upgrade.

Is DL-Alanine safe for human consumption?

Understanding DL-Alanine

DL-Alanine stands out as an amino acid with a unique profile. Every protein we eat contains amino acids, which work as the body’s building blocks. Dietary supplements and some processed foods often list DL-Alanine as an ingredient. For anyone without a background in biochemistry, the “DL” prefix can look confusing. It signals the product contains both D- and L- forms of alanine mixed together. In natural proteins, only L-alanine shows up, but both forms share the same basic molecule, rearranged in opposite mirror images.

The Human Body and Alanine

Alanine doesn’t attract the flashiest headlines. It’s one of the non-essential amino acids, meaning the body can make it on its own. Still, it plays a critical role in turning protein into energy and supporting healthy blood sugar. L-alanine helps ferry nitrogen and carbon in the body, which supports muscle recovery and organ function. D-alanine appears rarely in nature, mostly produced by bacteria—not humans. Some research points to bacteria in the gut producing small amounts of D-alanine, suggesting that humans can process small doses without trouble.

What Does the Research Say?

On the safety question, animal studies and in vitro work guide much of what we know. At reasonable intake levels, DL-alanine doesn’t show any obvious toxic effects. Researchers checked for negative impacts on liver and kidney function. Even after repeated use, those organs remain healthy at standard concentrations, suggesting safety at levels far above what a regular diet could provide. In the rare event of severely high intake, studies point to mild digestive upset—nothing dramatic or life-threatening.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recognizes L-alanine as “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS). DL-alanine hasn’t received the exact same formal status, mostly because it pops up less often in diet or supplements. Still, no credible reports link DL-alanine with harmful side effects in typical scenarios. European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) panels reviewed related data and did not raise concerns for mammals, confirming a wide margin of safety for supplemental use.

Practical Use and Common Sense

Supplements carry the possibility of overdoing it. No one benefits from shoveling in giant amounts of any single amino acid, DL-alanine included. I’ve seen plenty of well-meaning friends order bucket-sized tubs of “muscle boosters” online, trusting a label more than their own research. The key is keeping everything in perspective. Alanine naturally shows up in meats, eggs, dairy, and beans, and diets balanced in whole foods easily hit the mark for healthy intake.

DL-alanine doesn’t replace medical treatment or careful nutrition planning. People with pre-existing kidney troubles or rare metabolic conditions benefit from checking with a trusted healthcare provider before stacking new supplements. Manufacturers sometimes push trendy amino acids as silver bullets for athletic recovery or energy, but eating real food and getting enough rest deliver a lot more results. The food industry uses DL-alanine in some flavor enhancers and protein fortifiers, but those doses stay low—nowhere near toxic thresholds.

Looking Ahead

With more research focused on the gut microbiome and how our bodies handle rare amino acids, new findings might reveal hidden roles for D-forms, including potential brain or immune benefits. For now, DL-alanine falls on the safe side for adults with no major health issues, as long as its use stays within sensible amounts. Tuning in to your body and making decisions based on established nutrition—not just ad copy or internet fads—goes a long way toward staying healthy.

What is the difference between DL-Alanine and L-Alanine?

Alanine: Just One Letter, Big Difference

Alanine belongs among the building blocks of life, better known as amino acids. You see it listed as “L-Alanine” or “DL-Alanine” on supplement bottles, food labels, chemical catalogs—sometimes that “D” slips in there and people wonder what’s really going on. I remember back in college biochemistry labs, the professor drilled in that just flipping a molecule’s shape changes everything in biology. Alanine gives an easy way to see this in action.

The Two Faces of Alanine

There’s a crucial detail you’ll hear in organic chemistry: molecules can exist as mirror images, a lot like your left and right hand. L-Alanine is the version the human body uses naturally. Every protein in your muscles and organs relies on this specific “handed” version to function. Our cells recognize it perfectly, almost like a key fitting a lock.

DL-Alanine means you’ve got a mixture: half L-Alanine, half D-Alanine. Chemically, both parts look similar, but life can’t always use them the same way. Biology is picky that way. Bacteria sometimes utilize D-amino acids (including D-Alanine) in their cell walls, but humans really only process the L-type efficiently.

Health and Nutrition: Don’t Toss the Wrong Coin

Walk into a supplement shop or scan ingredients lists—L-Alanine is in workout boosters and clinical nutrition shakes. Since our bodies “speak” in L-forms, it’s the right fit for supporting muscle, fueling the brain during stress, and helping manage blood sugar. I’ve seen health enthusiasts pay extra just to confirm the supplement picked is pure L-Alanine. If you see “DL-Alanine,” it means you’re only getting half the active ingredient your system needs.

With DL-Alanine, the D-form doesn’t harm most people, but it won’t do much good for vegetarian diets or fitness plans counting on exact muscle protein building blocks. In rare health applications, researchers explore D-amino acids to fight bacteria. The average person, though, should focus on L-Alanine for nutrition.

Why Chemistry Isn’t Always Just for Textbooks

This all gets practical pretty fast. Chemists can make alanine in the lab in two ways: from living cells (which churn out pure L-Alanine), or by a synthetic route creating both mirror images—DL-Alanine. Lab synthesis gives a cheaper product, but not the pure stuff that food or supplement manufacturers want. They often need extra steps to toss out the D-part before shipping L-Alanine to sports nutrition factories.

Mistakes can happen too. In 2012, I read about contaminated amino acid supplements causing confusion among athletes and even in hospital settings. That’s why the medical and nutrition world insists on tested, labeled forms of amino acids. It’s easy to assume lab-made and nature-made ingredients act the same, but biology disagrees. Even a subtle difference in shape changes how nutrients work, and this affects not only health outcomes but also the reputation of supplement companies.

Clear Choices: What Can Be Done?

For consumers, reading labels matters more than ever. Choose L-Alanine when it comes to dietary needs—ask for certified products if you’re unsure. For supplement companies, transparency and third-party testing keep trust high. Chemists and product makers can work together to purify ingredients before they hit the shelves. Regulatory bodies need strong guidelines, pushing for clear labeling around amino acid form. Better labeling means fewer mistakes, healthier customers, and a level playing field in the nutritional market.

What are the recommended dosages for DL-Alanine?

DL-Alanine – Who’s Using It, and Why?

From what I’ve seen in supplement and health circles, DL-Alanine doesn’t attract the same hype as things like glutamine or creatine, yet it quietly sits on shelves with claims ranging from energy support to metabolic assistance. Exercise enthusiasts and some folks exploring amino acids for diabetes or rare metabolic disorders sometimes look for information about taking this supplement, hoping to boost daily performance or address specific health concerns.

Recommended Dosages Are Not One-Size-Fits-All

A search through nutrition textbooks and research studies shows there isn’t a widely recognized, official daily intake for DL-Alanine. Essential amino acids have clearer cutoffs; DL-Alanine enters a fuzzier territory because the human body produces the L-form easily, and racemic mixes aren’t standard in diets. Many supplement bottles suggest somewhere between 500 mg and 3,000 mg per day. That wide gap underlines the lack of consensus across professional groups and the absence of long-term human studies.

People I trust in nutrition—registered dietitians—usually urge anyone interested in amino acid supplements to look for advice from a healthcare professional, especially when it comes to nonessential ones like DL-Alanine. No large-scale clinical trials can give a gold-standard dose for healthy adults or athletes. Research on medical uses (like support for certain metabolic conditions) involves careful calculations by doctors, often far outside anything found in store-bought capsules.

Risks of Overdoing It

It’s tempting to assume that if an amino acid is “nonessential,” taking extra can only help. I’ve seen people double up on supplements hoping for a big boost, only to experience bloating, stomach upset, or headaches. High doses of some amino acids can stress out the kidneys, throw electrolyte levels off, or interact with other medications. This isn’t alarmism—several case reviews show that non-prescribed use of amino acid combinations sometimes ends in ER visits due to unpredictable side effects.

Research in animals offers clues on safety but doesn’t directly translate to what humans should take. Those studies sometimes involve doses far above what anyone would use, making it hard to give people a straight answer. Anyone managing a chronic illness or taking prescription drugs should approach these supplements with extra caution, since adverse interactions may not be obvious until symptoms appear.

How I Approach Supplements Like DL-Alanine

I like information grounded in transparency—research that spells out who participated, what they took, and what happened. Right now, the science for DL-Alanine leaves big question marks. Until there’s credible data on safety and results in real-world populations, I put more trust in a balanced diet and only explore supplements after talking through the details with a clinician. Anecdotes from bodybuilders or wellness bloggers offer perspective, but they won’t replace clinical evidence or honest label practices.

What Would Make DL-Alanine Use Safer

The supplement industry could do a better job posting batch testing results and explaining where their ingredients come from. Regulators can advance clear policy about labeling, so buyers know what they’re getting. Medical professionals could keep pushing for research that tracks actual human outcomes with these lesser-known amino acids—preferably in a way that includes people of different ages, genders, and backgrounds.

Until more facts exist, treating DL-Alanine doses as something to experiment with alone isn’t wise. Guided advice beats guesswork, whether you’re an athlete, a person with a rare disease, or simply curious about new ways to support your health.

Are there any side effects associated with DL-Alanine?

What Is DL-Alanine?

Amino acids pop up everywhere in nutrition circles, and DL-alanine finds its place among them. Our bodies count on alanine to help turn food into energy and keep muscles working. The DL version combines two forms: D-alanine and L-alanine. That might sound technical, but all it means is that the mix covers both types the body can encounter.

Looking at Side Effects

Supplements make big promises, but the honest question always comes up: what risks tag along? Most people get enough alanine just by eating balanced meals—chicken, eggs, fish, beans, and even leafy greens have you covered. Lab studies back this up. For most healthy adults, tossing in a little more alanine rarely leads to trouble. Still, gulping down high doses isn't harmless for everyone.

Some folks notice stomach upset, a flush of warmth, or a twinge in their gut after too much alanine. On rare occasions, headaches or tiredness follow. Most of these signs fade once the extra alanine clears out. That doesn’t mean “no risk.” Overdoing it can mess with blood sugar, especially if you already take diabetes meds. In my own experience testing amino acid blends during marathon prep, sticking with recommended amounts kept me out of trouble. Going well above, though, brought on weird sweat and heavy legs—not exactly a performance booster.

The International Society of Sports Nutrition and other research bodies regularly review these compounds. Most have not found a strong reason for panic in healthy adults, but anyone with kidney or liver problems should talk to a doctor first. The same applies if you already take medicines for metabolism or blood pressure.

Why Does This Even Matter?

Wellness trends shift fast, and supplement aisles only keep getting longer. The pressure to “hack” health with powders or pills never lets up. In the bigger picture, this makes it easy to forget that nutrition isn’t about piling on more, but about balance. For an everyday person, spending cash on DL-alanine won’t likely buy better results than improvements to daily meals. Data collected by the National Institutes of Health highlights how nutrients work best in their natural contexts—real meals, not isolated chemicals.

It’s tempting to believe there’s a shortcut to building muscle, breaking through a plateau, or just feeling sharper. Yet these aren’t problems solved by one ingredient, and no serious evidence suggests DL-alanine breaks the mold. Safety comes down to context—age, health status, and medication use all shape the equation. The reality is that most bodies have built-in checks and balances for handling extra amino acids, but this system can get overwhelmed with extremes.

Better Ways to Build Health

Supplements have their place—targeted, doctor-approved, filling in gaps for someone who can’t get all nutrients through food. For the rest of us, focusing on regular meals, sleep, and activity brings more lasting results. Reading labels, asking questions, and not falling for wild claims makes a difference.

Doctors and dietitians remain the best source of advice. If you’re considering DL-alanine or anything similar, get input from someone trained to weigh your health history and long-term goals. For now, prioritizing balanced eating and checking in with medical professionals beats rolling the dice with an unfamiliar supplement.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Aminopropanoic acid |

| Other names |

DL-2-Aminopropanoic acid DL-α-Alanine DL-alpha-Alanine |

| Pronunciation | /diː ɛl əˈleɪniːn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-Aminopropanoic acid |

| Other names |

DL-2-Aminopropionic acid DL-α-Alanine |

| Pronunciation | /diːˌɛl əˈlɑː.niːn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 302-72-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1719905 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:5950 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL714 |

| ChemSpider | 560 |

| DrugBank | DB00129 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.751 |

| EC Number | 2.6.1.2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 67686 |

| KEGG | C00133 |

| MeSH | D000431 |

| PubChem CID | 5950 |

| RTECS number | AY2990000 |

| UNII | 9DLQ4CIU6V |

| UN number | 2811 |

| CAS Number | 302-72-7 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `/models/molfile/dl-alanine.mol` |

| Beilstein Reference | 1712787 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:59597 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL598 |

| ChemSpider | 702 |

| DrugBank | DB00129 |

| ECHA InfoCard | EC number: 200-273-8 |

| EC Number | EC 2.6.1.2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 5276 |

| KEGG | C00133 |

| MeSH | D02.705.400.040 |

| PubChem CID | 5950 |

| RTECS number | AY2990000 |

| UNII | QF0EJTO2CB |

| UN number | 2811 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2 |

| Molar mass | 89.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.432 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 166 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.85 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.000104 hPa (25 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.34 (carboxyl), 9.69 (amino) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 2.34 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.73 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.498 |

| Viscosity | 1.04 mPa·s (at 20 °C, 10% in water) |

| Dipole moment | 1.35 D |

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2 |

| Molar mass | 89.09 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.432 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | 166 g/L (20 °C) |

| log P | -2.85 |

| Vapor pressure | 0.01 mmHg (25°C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.34 (Carboxyl), 9.69 (Amino) |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb: 10.14 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.46 x 10^-6 cm^3/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.498 |

| Dipole moment | 3.25 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 86.6 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -528.6 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1476 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 96.7 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -528.3 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1507.3 kJ·mol⁻¹ |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AA22 |

| ATC code | A16AA09 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 16600 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat LD50 = 12,890 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | AY8400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 3.9 g |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) |

| Precautionary statements | Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames and other ignition sources. No smoking. Wash hands thoroughly after handling. Wear protective gloves/protective clothing/eye protection/face protection. IF ON SKIN: Wash with plenty of water. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Autoignition temperature | 485°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat 12,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): Oral rat LD50 = 7900 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | AW1400000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 30 mg/kg bw |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

L-Alanine D-Alanine Beta-Alanine Glycine Serine |

| Related compounds |

L-Alanine D-Alanine β-Alanine Glycine Serine |