Disodium Succinate: A Down-to-Earth Look at a Quietly Important Ingredient

Historical Development

Disodium succinate has deep roots in both food processing and chemical engineering, dating back to the early twentieth century. Chemists started exploring succinic acid and its salts as byproducts of fermentation, stumbling across disodium succinate in the process. Japan’s Ajinomoto Co. helped popularize it in food circles after World War II, mainly due to its umami-enhancing qualities. Over the decades, the stuff made its way into Western food labs and manufacturing plants, quietly boosting flavors and serving as a reliable buffer in various chemical processes. This isn’t an overnight discovery. It’s the product of decades of close observation: people noticed fermented, umami-rich foods packed a flavor punch, and science at the time linked that to molecules like disodium succinate. Now it shows up in kitchens, factories, pharmaceutical companies, and research labs on just about every continent.

Product Overview

Disodium succinate sounds complicated, but all it really does is deliver a savory taste and stable performance. You’ll find it written as E364 on ingredient lists in Europe. It sneaks into broth powders, ramen seasonings, and even some vegan meat substitutes for that signature meaty depth. Scientists often reach for it as a chemical intermediate or pH buffer. The compound keeps low-key, never grabbing headlines, but it reliably shows up where both taste and chemistry demand something that packs a punch without a trace of color or odd odor. Food manufacturers appreciate its consistent quality and flavor enhancement, so it remains a staple for anyone tinkering with savory foods or balancing out acidic formulas.

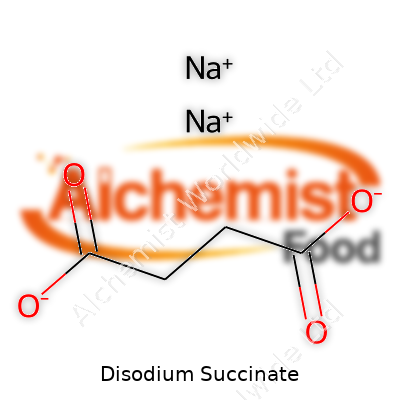

Physical & Chemical Properties

Disodium succinate comes as a white, crystalline powder. It dissolves in water, delivers a salty umami flavor, and leaves the other senses alone; no strong smell, no color, no annoying residue. Structurally, it’s the disodium salt of succinic acid (C4H4Na2O4). It melts around 200°C with decomposition, which means it holds its own under typical cooking or processing conditions. With a molecular weight of about 162 grams per mole, it isn’t heavy, mixes well, and won’t shift the structure of a recipe or formula. In my own hands, the dry powder clumps a little in humidity, but always blends back in if you work it with a whisk or dissolve it in a warm liquid.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Food-grade disodium succinate shows up on ingredient lists as E364 in Europe and “disodium succinate” elsewhere. The usual purity hits at least 99%, sometimes hovering a bit higher for laboratory or pharmaceutical suppliers. Particle size can matter for instant soup mixes or tablets—standard grades pass through 80- or 100-mesh screens with ease. Moisture matters, too; tighter specs keep water content below 1%, since extra moisture leads to caking and loss of flow. For regulatory comfort, suppliers provide certificates of analysis, batch numbers, and clear labeling showing country of origin, net weight, and recommended storage. Buyers and auditors demand this transparency so there’s no confusion when an inspector checks the stockroom.

Preparation Method

Manufacturers produce disodium succinate mainly by neutralizing succinic acid with sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide, followed by filtration and crystallization stages. The process begins with fermented or petrochemically derived succinic acid, typically sourced by fermenting sugars with specialized bacteria. Once the acid hits the purity mark, it meets a sodium base in a reaction vessel; that forms disodium succinate and releases water. Cooling the mixture encourages crystals to form, which are then filtered off. Modern plants favor closed systems to keep things clean and maximize recovery, and some even recycle wash water. Drying and quality checks finish the job, getting the powder ready for shipping in sealed drums or bags.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

The chemistry behind disodium succinate isn’t flashy, but it’s reliable. It acts as a buffer in solution, keeping pH steady, which matters in both food and industrial processes. In the right hands, it morphs into other useful chemicals: heating with acetic anhydride yields succinic anhydride. Chemists turn it into succinimide, often used in pharmaceuticals and as a starting point for more complex molecules. Disodium succinate itself isn’t reactive in the sense of bursting into dangerous transformations, but under heat or acidic conditions, it will release succinic acid again, so recipes and formulations plan for that shift. I’ve seen experimental chemists reach for it when they need a safe, predictable source of succinate ions; nothing fancy, just pure reliability.

Synonyms & Product Names

Disodium succinate often plays hide and seek on labels. You’ll see it called sodium succinate, E364, and sometimes succinic acid, disodium salt. Some suppliers add “food grade” or “pharmaceutical grade” for clarity. Asian ingredient lists, especially in Japan and Korea, often use the katakana version, splitting the syllables for sound but not meaning. A few research catalogs specify the purity or hydrate form for accuracy. Even with all these names, the chemical formula never lies—one look at C4H4Na2O4 and the story comes together.

Safety & Operational Standards

The more I work with disodium succinate, the more I notice how little drama it brings to the table. Safety data sheets list it as low risk—non-toxic in normal quantities, not a known allergen, and safe in food at recommended levels. In a factory or kitchen, good manufacturing practice still rules: avoid inhaling dust, keep bags sealed, clean up spills with water. Regulatory agencies set upper limits for food use—most countries land at a few thousand milligrams per kilogram in processed products, far below anything you’d hit in everyday meals. For pharmaceutical uses, purity and trace element limits get tighter, but no horror stories stand out. Annual audits, spot checks, and clear batch documentation serve as the backbone for operational safety, more about consistency than any acute risk.

Application Area

Disodium succinate wears many hats across industries. In food, it sits in seasoning mixes, instant noodles, snack coatings, and frozen meals, making up the backbone of modern umami flavor science. Chefs use it—at home or in high-tech kitchens—to boost depth in vegetarian dishes and broths. Pharmaceutical folks value it as a buffer in injectables and tablets, quietly stabilizing pH so active ingredients stay effective. Industrial chemists rely on it in electroplating baths and cleaning formulations, where predictable chemical behavior matters more than glamour. Even lab researchers keep it on the shelf for running electrophoresis gels or prepping metabolic assays on a budget. Its versatility keeps it in demand, even if most consumers never read its name.

Research & Development

R&D teams across the world keep poking at disodium succinate for new uses. Food scientists push ahead with clean-label initiatives, seeking fermentative sources of the salt that appeal to natural ingredient advocates. Biotechnologists use engineered microbes to boost yields from agricultural waste, cutting environmental footprints and opening the door for cheaper production. Pharmaceutical firms keep studying disodium succinate as both a stabilizer and a possible active ingredient in metabolic or kidney treatments. Some university labs even look to tweak the molecule—adding functional groups or blending with related salts—to create novel buffers or next-generation food fortifiers. My own experience in product development showed just how handy it is—you can try new formulas, knowing that this backbone chemical won’t pull any surprises.

Toxicity Research

Decades of toxicity research back up disodium succinate’s reputation for low hazard at typical exposure levels. Oral toxicity in rats lands in a safe range, hundreds of times higher than daily consumption in food. Animal studies show minimal impact on organ health or biochemistry at accepted doses. Allergic reactions crop up only in rare cases of massive misapplication, and even then, symptoms rarely escalate. Long-term studies show the body metabolizes and excretes succinate quickly via normal biochemical pathways—the Krebs cycle chews it up and spits it out as carbon dioxide and water. Regulatory reviews in Japan, the US, and Europe all reach similar conclusions; within recommended limits, the salt poses no meaningful risk to human health or the environment.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, disodium succinate’s future seems tied to shifts in plant-based protein, sustainable food production, and greener chemical manufacturing. Startups and established firms both explore microbial fermentation pathways that use food waste—not petrochemicals—as feedstocks. There’s ongoing work to enhance flavor profiles in low-salt or plant-based dishes, a spot where disodium succinate already shines. Cleaning product manufacturers evaluate its buffering power in more eco-friendly bleach alternatives. Biochemists tease apart its possible medical benefits, especially for metabolic support, chronic fatigue, and kidney health, even if these leads remain early-stage. Affordable, reliable, and safe, disodium succinate makes a case for itself as a backbone ingredient for healthier and more sustainable products. It earned its place through steady results—not flash—and will likely stick around as people expect more from everyday ingredients.

What is Disodium Succinate used for?

Finding Flavor in Familiar Foods

Walking through any supermarket, you’ll stumble on packaged snacks, instant noodles, and frozen dishes all promising bold flavor. Behind the taste of “umami”—that mouthwatering, savory note—disodium succinate often does some heavy lifting. It shows up on ingredients lists, especially in Asian-style broths and meat-flavored seasonings. Beyond simple flavoring, it works as a salt substitute that can enhance salty, meaty, or roasted profiles without that overwhelming brininess table salt brings.

Disodium Succinate’s Role in Modern Cooking

Chefs chasing consistency lean on disodium succinate to deliver the same savory bite every single time. For home cooks exploring ramen or wanting a boost in vegan recipes, this additive can edge a broth closer to chicken flavor—without actually using animal products. The food industry prizes it for how it wakes up the senses and rounds out the taste of processed snacks, noodle cups, and seasonings.

Understanding Food Labels and Safety

Reading “disodium succinate” on food packaging raises eyebrows. People want to know if it’s safe. Regulatory bodies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) approve its use in small amounts. Decades of tests show few risks when consumed at levels found in food. Even so, eating a wide range of whole foods—fruits, vegetables, fresh proteins—keeps intake naturally low.

A few years back, some folks worried about its link to sodium, especially with hypertension rates climbing worldwide. One teaspoon of the additive contains less sodium than straight salt, but those watching their intake should stay aware. Checking nutrition labels and ingredient lists becomes a tool for anyone trying to cut back while still looking for bold flavors in their meals.

Health, Choice, and Finding Alternatives

People often ask, “Why not just stick to traditional seasonings?” Not every kitchen works at the same pace, and not everyone can simmer broth for hours. Disodium succinate brings convenience. Still, food companies shouldn’t lean too hard on additives when fresh ingredients can carry a dish. For anyone looking for alternatives, slow-roasted tomatoes, mushrooms, and kombu seaweed build umami in soups and stir-fries.

Eating should mean more than just convenience. Flavor enhancers like disodium succinate can help families who want quick dinners, but fresh herbs, citrus, or a well-seared mushroom can transform a dish—and bring health perks that a powder can’t. Following trustworthy sources, reading recent studies, and choosing whole foods keeps individuals in the driver’s seat.

Looking at the Bigger Picture

The rise of additives like disodium succinate traces back to busy lives and changing food habits. While safety data remains strong today, everyone benefits from knowing what goes into their meals. Companies committed to quality don’t hide ingredients. Cooking at home with basic but flavorful ingredients limits exposure to extra sodium and fills the table with color and taste. More knowledge always leads to better choices.

Is Disodium Succinate safe to consume?

What Disodium Succinate Brings to the Table

Sifting through ingredient lists, you might have spotted “disodium succinate” on packages of instant noodles, cured meats, or seafood snacks. It shows up as a flavor enhancer, prized for its savory, umami kick. Food makers add it because it doesn’t just round out taste—it highlights saltiness and boosts meaty notes. It’s common in Asian cuisine, where bold, layered flavors matter.

What Science Says About Safety

I’ve checked the data behind ingredients like this before tossing them into my cart. Disodium succinate has caught the eye of food regulators in places like the US, Europe, and Japan. These agencies look at toxicity, how the body handles it, and whether it lingers in organs. The bottom line from current reviews: It generally passes safety checks for average use in food.

Your body recognizes succinic acid—one half of the disodium succinate pair. It churns out small amounts of this compound as part of normal metabolism. Once you eat food with disodium succinate, it breaks down to succinic acid and sodium in the gut. Tests show that rats and humans process and clear these safely, unless eaten in excessive amounts far beyond what’s found in snacks or broths.

Possible Health Concerns

No food ingredient fits everyone the same way. Some people pay close attention to sodium numbers, worrying about blood pressure, especially in a world full of salty processed food. Disodium succinate contains sodium, so it adds to your daily total. For or those with kidney problems, even small extra sodium can strain the system. There’s another piece to the story: groups studying food additives keep their eyes open for allergies or intolerance, but disodium succinate isn’t known to trigger reactions in the general population.

Long-term studies in animals and test tubes haven’t revealed cancer or serious issues tied to normal dietary intake. The same goes for developmental problems. European and Japanese food safety authorities didn’t find enough evidence of harm at low levels, and so they stamped it with an Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI).

Why Ingredient Transparency Matters

It gets easier to trust your food when labels are clear and you know why certain chemicals go in your dinner. Food makers benefit from solid science and responsible limits, but shoppers should have the tools to figure out what works for their bodies.

Cooks at home can skip flavor enhancers like disodium succinate altogether by building umami from fermented foods, mushrooms, or meat. Yet some don’t have the time or budget for scratch cooking every day, and reach for packaged options. Here, the ask isn’t just safety. I'd like to see tighter labeling laws and public food education. That way, anyone can spot high sodium before it sneaks onto the dinner table.

Paving a Safer Path Forward

Government regulators should keep demanding transparency and strict upper limits in processed foods, especially in products aimed at kids. Schools and hospitals can lead by example, focusing on fresh foods and educating about hidden sodium in additives. Food companies could set up clearer messaging—simple icons or sodium warnings—on packaging. If public health groups team up with teachers and chefs, families get more tools to steer away from hidden risks and toward better meals.

Staying alert and informed keeps everyone safer. Food choices, after all, shape health for years to come.

What are the side effects of Disodium Succinate?

Why Disodium Succinate Turns Up in So Many Foods

Disodium succinate doesn’t ring many bells outside food science circles, but anyone who’s unwrapped a bag of chips, ramen, or some frozen dumplings has eaten it. This flavor enhancer, pulled from succinic acid, gets tossed into soups, sauces, seasonings, and packed snacks. The food industry leans on it for a savory punch—think “umami,” that fifth taste that lingers in broths and meats. People rarely notice its presence because it's tucked away under a longer list of flavor additives on most labels.

The Short List of Side Effects

Most people won’t notice any difference after eating something with disodium succinate. Multiple food safety authorities, including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), labeled it as “generally recognized as safe.” This recognition doesn’t mean it’s side-effect-free for everyone. Folks with a sensitive digestive system sometimes talk about stomach rumbling, mild cramps, or bloating after a meal packed with flavor enhancers. Eating large quantities over a short time can spark these gut-based grumbles.

Allergy reactions to disodium succinate remain rare. Still, if someone has a unique allergy or sensitivity to other sodium-based food additives, they might feel itchy, break out in mild hives, or feel a tingling around the mouth. These allergic responses shouldn’t be brushed off, especially in people with a history of reacting to other “E-number” additives.

Sodium-based additives add up, especially for people trying to keep a lid on their daily sodium intake. Disodium succinate itself won’t push most folks over the edge, but combine it with sodium lurking in bread, deli meats, and canned goods, and daily limits start to get close. The American Heart Association points out links between overdoing sodium and higher blood pressure—a risk that grows with age, genetics, and other lifestyle habits.

What Food Science Says About Its Safety

Toxicology reports and animal studies back up disodium succinate’s safety at standard amounts in food. The European Food Safety Authority reviewed it and saw no sign of it building up toxic byproducts in the body. Also, they found that the human system is capable of breaking down succinate without extra strain on the kidneys or liver. It doesn’t linger in bones or organs, and anyone with healthy kidneys filters it out pretty smoothly.

Common-Sense Paths to Safer Eating

Paying close attention to food labels gives everyone more control over what ends up in their cart. People living with kidney conditions or high blood pressure benefit most from keeping sodium levels in check. Swapping ultra-processed foods for whole, fresh options leaves less room for surprise flavor enhancers. Cooking at home with raw veggies, lean meats, and plain spices keeps things simple—and cuts mystery additives.

If someone does run into a reaction, reaching out to a healthcare provider helps sort out whether disodium succinate is the real troublemaker. Supporting research shows that open conversations with dietitians or doctors make a difference, especially for people managing other health conditions.

Building Smarter Food Habits

Disodium succinate belongs on the long list of food additives that show up quietly in the modern diet. Side effects rarely hit hard, but anyone can take steps to eat smarter by paying attention to labels, choosing fresh foods, and knowing the signs of sensitivity. Learning what goes into every meal makes it easier to feel good, stay healthy, and reduce the odds of an avoidable reaction.

Is Disodium Succinate natural or synthetic?

What Is Disodium Succinate?

Disodium succinate shows up regularly on food labels, especially for snacks, instant noodles, and seasonings. As a flavor enhancer, it stands out for delivering a rich umami punch. People paying close attention to food additives often wonder about the story behind it. To understand if it falls into the “natural” or “synthetic” camp, it helps to look at where it comes from, how producers make it, and its impact on health.

Tracing Its Origin

Succinic acid, the key raw ingredient, gets its name from amber, where it was first found. Plants, animals, and even humans contain small amounts of succinic acid as part of basic cell metabolism. The path from that natural acid to disodium succinate involves chemistry, but not all processes are the same.

Some manufacturers produce succinic acid using traditional fermentation. Microorganisms break down sugars or starches in controlled tanks, kind of like brewing beer. The succinic acid is captured and refined. After that, sodium carbonate or sodium hydroxide reacts with it, forming the disodium salt. This process keeps things close to their biological roots. There’s lab work, sure, but it starts from plants—corn or sugarcane quite often.

The other route involves petroleum-based chemical synthesis. Crude oil becomes the base for chemical reactions that build succinic acid molecules. The conversion to disodium succinate follows. In this approach, the connection to anything found in nature thins out. It’s efficient, and sometimes less expensive, but comes with more environmental baggage.

Labeling and Consumer Knowledge

In stores, products using disodium succinate rarely mention whether the compound was derived from fermentation or petrochemicals. Food labels only mention the chemical name, not its story. That gap can frustrate shoppers who want to opt for “cleaner” or “less processed” options. For manufacturers who use the fermentation process, certifying that fact through “natural flavor” claims or third-party organizations can boost trust. Some brands in Asia already highlight fermentation on their labels.

The push for transparency keeps growing. Clean-label trends show the demand isn’t just hype. A Consumer Reports study found almost three-fourths of U.S. adults are concerned about synthetic ingredients in food. Real, clear information about additives makes a difference at checkout.

Health and Safety

Extensive research and food safety evaluations, including those from the FDA, JECFA, and EFSA, find disodium succinate generally safe in food amounts. The body breaks it down just like natural succinic acid. Some people point to hyper-processed foods as a bigger issue, rather than this specific ingredient. Still, I believe shoppers should have a full picture to decide for themselves. Many want to support processes lighter on the planet and closer to nature.

Solutions for Clarity

Manufacturers could adopt more visible, straightforward labels. Food certifications (Non-GMO, Organic) set a blueprint—why not something similar for fermentation-derived food additives? Strong partnerships between watchdog groups and industry could deliver guidance people actually see and understand. Companies with sustainable supply chains might find a marketing edge by sharing their practices.

People, like me, who try to eat mindfully benefit from better transparency. I have started reaching out to brands requesting details on ingredient sourcing. If more people speak up, the industry listens. With clear info, values drive choices—not just price tags or buzzwords.

Can Disodium Succinate be used in vegetarian or vegan products?

Looking at the Source

Take a walk through grocery aisles and you'll spot “disodium succinate” on ingredient labels, especially in savory snacks, instant noodles, and plant-based meat alternatives. The ingredient brings a rich, meaty flavor, a taste called umami. For those avoiding animal products, the big question sits not with the name itself but with what lies behind it: How exactly is it made?

Manufacturers use different ways to make disodium succinate. Most commercial production uses fermentation. This involves feeding microbes a sugar source—usually corn, wheat, or tapioca. The microbes process the sugar and create succinic acid. Chemists take that succinic acid and react it with sodium compounds to get disodium succinate. Some factories still use animal ingredients, including animal fats or byproducts, as feedstock for the microbes. It isn’t common, but it happens. This issue often gets lost beneath marketing claims and catch-all ingredient lists.

Vegetarian or Vegan?

Most of what you see on grocery shelves comes from plant sources. In Japan and China, where disodium succinate often flavors ramen seasonings and snack foods, top suppliers rely mostly on fermentation with plant-based sugars. I’ve spoken with formulators in the food industry who say plant-based supply chains dominate because they save money and sidestep religious or ethical objections. Still, not every producer reveals the full backstory. Labels don’t spell out whether fermentation used plant or animal feedstocks. Even vegan certification agencies have taken time to catch up, and not every country has airtight vegan labeling standards.

Why It Matters

People who follow vegetarian or vegan diets have good reasons to care. For years, companies sneaked animal-derived ingredients into all kinds of processed foods. Somebody avoiding animal products for health, religious, or ethical reasons deserves to know what’s going into their food. The flavor-boosting power of disodium succinate has made it a star in making “plant-based” foods taste savory and satisfying. But if the source doesn’t match the values on the package, that trust cracks.

Digging for Answers

Food makers don’t always make it easy to find out whether disodium succinate is vegan-friendly. Calling or emailing companies brings mixed results—customer service lines sometimes give generic answers. I’ve found that certified vegan or vegetarian labels give the best assurance. In my own kitchen, I look for certification by groups like Vegan Action, The Vegan Society, or official kosher and halal certifiers. These organizations require documentation that covers how each ingredient is sourced and processed. Transparency matters—nobody wants to feel tricked by technicalities or vague promises.

What Can You Do?

If you eat vegan or vegetarian, keep asking questions. Push companies to provide supply chain details. Social media and direct inquiry put pressure on brands to clean up their sourcing and labeling. Supporting brands with strong certifications also sends a clear message. For home cooks interested in a pure option, food-grade succinic acid (the precursor to disodium succinate) from reputable plant-based sources can be turned into savory seasoning blends. Researchers and consumer advocates can push for stricter laws that force transparency on ingredient sources.

To move forward, food companies must speak clearly about the true origins of ingredients like disodium succinate. As more people choose plant-based eating, clear sourcing and honesty build lasting trust—one label at a time.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | disodium butanedioate |

| Other names |

Sodium succinate Disodium butanedioate E363 Succinic acid disodium salt Succinate, disodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /daɪˈsəʊdiəm səksɪneɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | disodium butanedioate |

| Other names |

Butanedioic acid disodium salt E363 Disodium butanedioate Succinic acid disodium salt |

| Pronunciation | /daɪˈsoʊdiəm səksɪneɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 150-90-3 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1636184 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:48696 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1375 |

| ChemSpider | 12651 |

| DrugBank | DB04418 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03e179e1-69e6-45fe-84e2-589095c3a76d |

| EC Number | 299-033-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 136217 |

| KEGG | C06423 |

| MeSH | D020432 |

| PubChem CID | 23672345 |

| RTECS number | WSU900K79E |

| UNII | WJ9U09LMR4 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 150-90-3 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | `3D model (JSmol)` string for **Disodium Succinate**: ``` C(C(=O)[O-])C(=O)[O-].[Na+].[Na+] ``` |

| Beilstein Reference | 412222 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:46747 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL3184974 |

| ChemSpider | 83581 |

| DrugBank | DB11272 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 03-2119440414-53-0000 |

| EC Number | 299-332-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 6358 |

| KEGG | C01740 |

| MeSH | D002963 |

| PubChem CID | 13390 |

| RTECS number | WV8300000 |

| UNII | 8K8Z6G48A9 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID2020845 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Na2C4H4O4 |

| Molar mass | 210.14 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.64 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Moderately soluble |

| log P | -4.55 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 5.21 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 12.6 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.420 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 2.50 D |

| Chemical formula | Na2C4H4O4 |

| Molar mass | 162.04 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.6 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | Freely soluble |

| log P | -4.22 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 5.21 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.6 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.432 |

| Dipole moment | 2.62 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 151.0 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1087.3 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1537.1 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 173.2 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1617.12 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2120.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A15AA07 |

| ATC code | A15BA04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Eye irritation, Skin irritation, May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS) |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P273, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 96 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (Oral, Rat): 8015 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Disodium Succinate: "8000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WHV08950 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 10 mg/m3 |

| REL (Recommended) | 0 - 0.05% |

| GHS labelling | GHS labelling: "Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008 (CLP/GHS). |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to the Globally Harmonized System (GHS). |

| Precautionary statements | Wash hands thoroughly after handling. If in eyes: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present and easy to do. Continue rinsing. If eye irritation persists: Get medical advice/attention. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 1, Flammability: 1, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Flash point | > 214°C |

| Autoignition temperature | AUTOIGNITION TEMPERATURE: 400°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 oral rat 8017 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LC50 (rat, oral): 8000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | NT8050000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 0.05 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 500 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Not listed |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Succinic acid Sodium succinate Monosodium succinate Sodium fumarate Disodium maleate |

| Related compounds |

Succinic acid Monosodium succinate Succinic anhydride Dimethyl succinate Succinyl chloride |