Curcumin: More Than Just Yellow in a Spice Rack

Historical Development

Growing up in households where turmeric was as common as salt, I always thought the bright yellow stain on my mother’s hands was nothing more than the colorful mark of a busy cook. Only later did I find out this yellow came from curcumin, a compound dug out of turmeric’s roots long before modern labs tried to bottle it. In ancient Ayurvedic and Chinese traditions, healers counted on turmeric for swelling and digestive issues, but it took centuries for curcumin to earn a name of its own. By the 1800s, European chemists pulled curcumin in its pure form, and from there, it wasn’t just a kitchen secret anymore; it entered labs, clinics, and factory floors. Curcumin stepped from remedy to research subject, carrying both centuries of culinary wisdom and a growing stack of scientific evidence.

Product Overview

Today’s curcumin comes in an impressive line-up, sold as pure powder, capsules, tablets, and even mixed into drinks and cosmetics. Most products promise high “bioavailability,” which means your body can actually use the stuff you swallow. This is a big deal because natural curcumin from turmeric doesn’t dissolve well and leaves the body quickly. Modern products often pair it with piperine from black pepper or bind it to phospholipids so more curcumin can reach the bloodstream. Walk through any supplement aisle or search through e-commerce sites, you’ll see names like “Curcumin C3 Complex,” “CurcuWin,” or “Meriva,” all with slight twists in processing and formulation but banking on the same golden molecule.

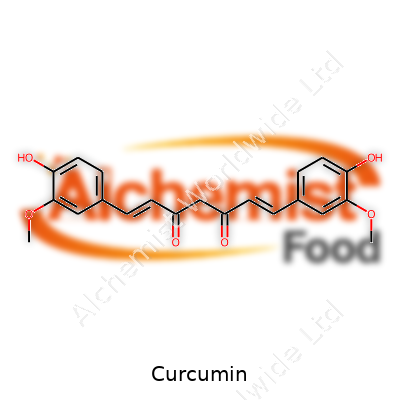

Physical & Chemical Properties

In the hand, curcumin looks like a bright orange-yellow powder, gritty but fine, with a mild earthy smell. Toss it in water, it barely dissolves, leaving a colorful ring along the glass. Curcumin’s melting point hovers around 183°C so unless you’re running a lab oven, it’s not melting for anybody’s curry. Its structure—technically, a polyphenol—lets it act as a scavenger against some of the nastiest troublemakers in the body, like free radicals. It shows promise in neutral chemical processes, and that underpins much of its reputation as an antioxidant, which is why wellness brands spotlight it in bold letters.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

If you’re buying curcumin for commercial use, the details count: most extracts contain at least 95% curcuminoids, a group of compounds in turmeric made up mostly of curcumin itself along with demethoxycurcumin and bisdemethoxycurcumin. Reputable suppliers point this out on labels, along with information about heavy metals and solvent residues, since safety rules run tight in the supplement industry. Certificate of Analysis (COA), GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) marks, and batch traceability show up on serious products. Ingredient lists also note excipients or extra carriers, which can affect absorption.

Preparation Method

Industrial-scale production of curcumin skips the mortar and pestle. Processors start with turmeric rhizomes, drying and grinding these into a powder. Extraction usually depends on solvents like ethanol or acetone. The powder soaks, the liquid pulls out the active curcuminoids, and technicians push away unwanted fractions. The concentrated extract goes through purification, often via crystallization, and then gets dried. Finished curcumin undergoes several rounds of testing before getting sealed for sale. In my earlier food chemistry work, it was easy to notice that even small changes in extraction temperature or solvent concentration change the outcome.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Researchers eye curcumin’s chemical backbone, constantly tinkering to squeeze out benefits. One common trick involves attaching sugar groups (glycosylation) or fat-loving tails (lipidation) to boost its uptake by human cells. Some labs tinker with nanoparticles, wrapping curcumin to help it slip past digestive juices and avoid quick breakdown. Curcumin’s keto-enol system lets it react with a lot of things under different pH levels, which opens it up to role-play in various chemical reactions from color development in foods to being a fluorescence marker in assays and diagnostic kits.

Synonyms & Product Names

Curcumin goes by many names—Curcuma longa extract, diferuloylmethane, Natural Yellow 3, E100—and each pops up on different product labels or regulatory references. In Europe, E100 flags it as a permitted food colorant, giving that golden touch to cheeses and mustards. In supplement circles, terms like “turmeric curcuminoids” or “standardized turmeric extract” keep showing up, all tracing back to the same active molecule.

Safety & Operational Standards

Safe handling starts with knowing that while curcumin stains skin and fabrics, its safety record in dietary amounts stays clean. The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives sets a daily upper limit—3 mg/kg of body weight. Reactions usually stick with minor stomach upsets; only high, sustained doses have led to rare concerns in animal studies. On the factory floor, gloves, goggles, and dust control help cut down on mess and inhalation risks. Supply chains aiming for international sale keep an eye on ISO standards, particularly ISO 22000 for food safety management.

Application Area

Curcumin jumped from kitchen to clinic, winding through food, nutraceuticals, cosmetics, and even textiles. My own introduction came through simple recipes, but its reach in medicine for inflammation and possible cancer prevention gets top headlines. Beverage makers add it for color and plausibly wellness. Cosmetic brands promise “radiance” with curcumin creams. Animal feeds sometimes get boosted with curcumin to improve health markers in livestock. The food world sees curcumin as both a coloring and a shelf-life extender, slowing oxidation. Dentistry researchers test it for mouthwashes, and wound care brands apply it in healing ointments.

Research & Development

Interest in curcumin continues to fuel a growing landscape of clinical trials and patents. The biggest challenge? Most curcumin leaves the body before it can work its full effects, a problem that has sent researchers racing for improved delivery systems. Scientists develop phospholipid complexes, solid lipid nanoparticles, and various encapsulation approaches. Early clinical studies look at benefits in arthritis, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and even depression. The story isn’t all rosy—small sample sizes, short trial durations, and inconsistent dosing make it tough to draw solid conclusions, but academic labs and private start-ups keep pushing for better answers. A solid example is the daily deluge of PubMed listings for new curcumin-human trial reports, with data piling up faster than many other natural compounds.

Toxicity Research

Most studies flag curcumin as low in toxicity when taken in moderate amounts. Toxicology reports in rodents only show harm at doses far above what humans typically consume, hundreds of times higher than what’s sold over-the-counter. In rare cases, people with gallbladder disease run a higher risk with heavy turmeric or curcumin intake. Clinical trials often report mild digestive discomfort at very high doses, but negative effects remain rare. Agencies in the U.S., EU, and Australia vet curcumin safety and set upper limits for use in food and supplements, regularly reviewing animal and human data to keep exposure within a safe range.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the story of curcumin is far from over. As delivery technologies improve, there’s potential for wider use in therapies from metabolic disease to mental health. Agricultural researchers eye new waysto boost turmeric yields and purity, while synthetic chemistry offers a shot at creating even more potent curcumin analogues. Policy leaders push for tighter label rules and quality controls so that what’s promoted on packaging truly matches what sits inside capsules and bottles. Academic journals publish fresh data on new mechanisms of action almost monthly. My own perspective—shaped by kitchen experience and late-night research sessions—keeps me optimistic that in the coming decade, curcumin will move from household curiosity to a refined, science-backed supplement and therapeutic agent, provided that research keeps pace with marketing and that regulatory boards place consumer safety above sales pitches.

What are the health benefits of Curcumin?

The Heart Behind Turmeric

Curcumin gives turmeric its bold, yellow color and spicy scent. Many folks in my family, including myself, never paid much attention to it until stories about its healing powers started spreading across health blogs. Once I dug a little deeper, it became clear why curcumin grabs so much attention, not just in kitchens but in clinics and labs, too.

Taming Inflammation Naturally

Anybody who wakes up with stiff knees or sore hands knows inflammation isn't just for medical textbooks. Curcumin stands out for its natural anti-inflammatory punch. Researchers at the University of Texas and Mayo Clinic showed that curcumin interrupts the body’s inflammatory process by targeting specific molecules like NF-kB. That's the same pathway many pain relievers go after but without the stomach pain or risks of ulcers. In my own life, switching to meals rich in turmeric seemed to cut down the swelling in my joints after sweaty weekends or nights at the gym.

Fighting Oxidative Stress the Tasty Way

Everyone’s heard that free radicals damage our bodies daily, from UV rays or fried comfort foods. Curcumin steps up as a potent antioxidant, some studies say almost rivaling vitamin C or E. By neutralizing these pesky molecules, it supports cellular health, which matters as we age. That’s not just hype. Scientists from UCLA tracked volunteers taking curcumin supplements and saw improved memory and less plaque buildup in brain scans—data that sounded too good to ignore for anyone in my family worried about dementia.

Supporting Heart and Brain

Heart health keeps many folks awake at night, especially with rates of heart disease rising all over. Curcumin has a knack for improving blood vessel lining (endothelial function), which supports better blood pressure and circulation. Trials in both India and the US have shown more flexible arteries after regular turmeric consumption. My dad, stubborn about taking new pills, felt much safer blending turmeric into his daily curry than swallowing another tablet, and he saw his blood pressure inch downward a notch.

Curcumin and Digestion

Digestion can be an unpredictable beast, made worse by stress and convenience food. Curcumin helps the liver produce more bile, which means fats break down more smoothly and stomach cramping happens less often. People with irritable bowel syndrome or mild ulcerative colitis wrote about fewer flare-ups when they made turmeric part of regular meals. My aunt, who once swore off anything spicy, found turmeric milk soothed her stomach far better than most store-bought antacids.

How Much and How Often

Not every curcumin product gives the same results. Our bodies don’t absorb curcumin easily, so pairing it with black pepper (piperine) or taking it with healthy fats makes a noticeable difference. Nutritionists warn not to go overboard, sticking to about 500-2,000 mg per day in supplement form. Tossing a teaspoon of turmeric into food works for a gentler boost.

The Real Story

Curcumin won’t replace everything your doctor prescribes, but it brings a lot to the table for folks hoping to ease aches, support memory, or boost heart and gut health. A colorful spice rooted in tradition, curcumin proves that some natural remedies deserve a spot in modern routines. Always talk to a health professional before swapping or adding supplements to your lifestyle, especially with ongoing health conditions.

Are there any side effects of taking Curcumin?

Curcumin’s Health Buzz

Curcumin, the main compound in turmeric, shows up everywhere. From health food shelves to internet ads, plenty of promises get tossed around: less inflammation, pain relief, a boost to memory. Scientific research gives some of these claims backing, but what often gets skipped over is how curcumin affects people with different bodies, diets, and medical histories. I tried curcumin capsules one winter hoping they’d ease my stiff joints. The morning boost felt real, but I started getting stomach cramps if I swallowed capsules on an empty stomach.

Where Trouble Starts: Stomach and Digestion

Upset stomach, bloating, and diarrhea land at the top of the side effect list. Curcumin isn’t easy for the body to absorb, so supplement makers often pack it with extra substances to help with uptake—like black pepper extract, known as piperine. This combo can lead to even more digestive troubles. After my third day doubling the recommended amount, my stomach sounded like a marching band and wouldn’t let up until I went back to food-based turmeric. The harsh truth: More curcumin isn’t always better, and those without iron stomachs may find the after-effects not worth the dose.

Big Doses Bring Hidden Risks

Taking curcumin in large amounts for weeks or months bumps up the risk of headache and nausea. Some research draws connections between curcumin and reduced platelet function—that’s the “clotting” in your blood—and can make cuts and bruises worse for those who bleed easily. People already taking blood thinners, like warfarin, could face real danger. Doctors from the Mayo Clinic list drug interactions and warn that herbal supplements aren’t ‘risk-free’ just because they’re ‘natural.’

Not For Everyone: Care for Special Situations

People with gallbladder issues or stones should stay away from curcumin supplements. It stimulates bile production, which can make these conditions worse. Pregnant women also need careful guidance. Big doses show some risk and need steering by an experienced healthcare provider. The FDA doesn't regulate supplements as tightly as prescription drugs, so what’s on the bottle may not reflect what’s inside. Some powders get stretched with fillers or even heavy metals—especially in products from unverified suppliers.

Smart Steps and Real-World Solutions

Mixing food-based turmeric into drinks or meals, as cultures in India and the Middle East have done for centuries, creates a safer path for most people. Even then, heavy spice-eaters rarely get the extreme doses packed into many supplements. For anyone thinking about adding curcumin, a talk with a doctor makes sense, especially for those on medications or living with chronic health concerns. Labs at places like Johns Hopkins and Cleveland Clinic keep digging into what works, what doesn’t, and where problems arise, but honest conversations with health professionals and reading real research rather than catchy internet headlines help avoid trouble.

Supplements can fill gaps. They can also bring new problems. Starting small, paying attention, and reaching for trusted products go a long way. Curcumin’s story blends old wisdom and new science, but even the best ingredient needs a clear look at side effects before jumping for a quick health fix.

How should Curcumin be taken for best absorption?

The Struggle to Unlock Curcumin’s Benefits

Many people chasing the brightness of turmeric end up disappointed. Turmeric rhizome glows with reputation, but its real magic comes from curcumin. So many embrace this golden spice, hoping for better joints or a sharper mind, only to discover that just swallowing a capsule of plain turmeric has little effect.

Why Curcumin Just Won’t Stick

Pop a curcumin supplement and most of it will slip right out of your body, unabsorbed. The compound struggles with poor solubility—our guts quickly break it down and send it away before the body gets much use from it at all. Studies show that traditional curcumin powders barely nudge blood levels, even after heavy doses. There’s a reason why the wisdom of Indian cooking pairs turmeric with rich, fatty dishes: Grandma almost always knows what works.

Real-world Ways to Make Curcumin Work

People start with food because food makes sense. Cook turmeric into a curry, use coconut milk, and black pepper, and you’re already following top scientific advice. Here’s what matters if you want to see results:

- Add Fat: Mix curcumin into meals rich with oils or healthy fats. Fatty molecules help transport curcumin through the gut wall and into the bloodstream. Dishes simmered in ghee, olive oil, or coconut milk do the job.

- Pair with Piperine: Scientists showed that piperine, found in black pepper, can boost curcumin absorption by as much as 2000 percent. Even just a dash of pepper works—no fancy extract needed.

- Consider Formulations Backed by Research: Some supplement makers add working delivery systems—phospholipids, nanoparticles, or micelles. These forms raise bloodstream curcumin better than old-school powders. Brands using "phytosome" or "liposomal" technology often quote real absorption data.

Chasing the Dose That Matters

Even top-grade products need the right dose. Most research on joint discomfort or memory sharpness uses between 500 to 2000 milligrams of curcumin extract a day. Real turmeric root powder has far less curcumin than labeled extracts, so the form you pick matters.

Taking more than recommended won’t make benefits grow faster. Too much can sour the stomach and complicate medications. It’s smart to check with your healthcare provider, especially if you take blood thinners or have gallbladder issues.

What Works Has Proof

For years, I tossed turmeric into everything with mixed results. Only when I started using black pepper and making sure fat was in the mix did I notice a difference in post-exercise soreness. I also tried different brands—some made specific claims with published absorption data. The products combining curcumin with piperine in a softgel, or those labeled "curcumin phytosome," gave me fewer stomach issues and seemed more consistent.

Clear Steps Forward

Anyone hoping for health gains from curcumin faces a simple decision: strategy over routine. Start with real food at home, boost it with pepper and fat. If using supplements, look for evidence of improved absorption. Relying on older turmeric powders or skipping research-backed details wastes time and money. In this case, a bit of science and kitchen wisdom goes a long way.

Is Curcumin safe to use with other medications?

What Makes Curcumin Stand Out

Curcumin turns up in a lot of health discussions these days, often spotlighted as the secret behind turmeric’s golden punch. Many folks use it hoping to help with joint pain, inflammation, or simply to boost their overall well-being. Large-scale studies, such as those appearing in the Journal of Clinical Nutrition, keep finding links between curcumin and health benefits ranging from improved mood to lower inflammation numbers.

Plenty of people, including my own relatives, try curcumin capsules on top of the prescriptions they get for high blood pressure, diabetes, or cholesterol. The sticking point: mixing supplements and pharmaceuticals isn't a minor detail, especially as doctors see more patients stacking up medications as they age.

Curcumin Can Get Complicated

Whenever a new supplement gets popular, serious questions pop up about its safety next to common medicines. Curcumin isn’t just a harmless kitchen spice when packed into capsules at high doses. It’s been shown to interfere with several enzyme systems in the liver, especially the CYP450 family, which helps the body clear out everything from statins to blood thinners.

People dealing with conditions like heart disease, blood clots, or cancer will often take drugs that need those enzymes to work at their usual speed. Swallowing a turmeric supplement every morning without a second thought can mess with those medicines, making them less effective or raising their levels to unsafe heights. Anticoagulants such as warfarin, for instance, require careful monitoring since even a small boost in activity could set the stage for bleeding.

The National Institutes of Health posts regular warnings about curcumin’s risk of increasing the action of certain medications or acting as a blood thinner itself. Pharmacists have seen cases where people on both an aspirin regime and a turmeric supplement ended up with unexpected bruising.

Sorting Hype From Help

A recurring issue in supplement land: quality and purity. Unlike prescription drugs, curcumin products often don’t face strong FDA oversight. Different brands use different extract strengths and fillers, making it tough for people to judge how much they’re truly getting or whether any extra ingredients could complicate things further. In a ConsumerLab review, over 30% of turmeric supplements tested didn’t match their labeled content.

Doctors who keep up with the news on supplements regularly run across patients who don’t think to mention what vitamins, herbal teas, or health boosters they’re trying at home. I’ve seen people hand over a prescriptions list and forget to mention the bottle of “anti-inflammatory” capsules sitting in the bathroom cabinet.

What’s Needed for Safer Use

Talking openly during doctor visits matters. No one wants to make a small health habit a dangerous one by accident. In my own circle, a medication check-in every few months helps catch these mix-ups. National pharmacy chains also flag some interactions, but personal conversations help fill in the gaps.

Bringing in a registered dietitian or clinical pharmacist comes in handy for folks balancing more than a few pills or supplements. They can look at both sides—what the body needs and how it processes each drug or supplement. If research keeps pushing curcumin into the spotlight, healthcare providers and the supplement industry both carry a responsibility to inform, check quality, and talk about safe, realistic doses.

Curcumin isn’t a miracle ingredient or pure risk. Like much in health, it depends on context and communication. Taking those steps pauses potential trouble before it ever starts.

What is the recommended dosage of Curcumin?

Understanding Curcumin’s Role

Turmeric isn’t just a staple in the spice cabinet. The compound inside, curcumin, has found its way from curry to the world of supplements. People reach for it because research keeps turning up links to lower inflammation, fewer achy joints, and even help against some chronic illnesses. Still, picking the best dose isn’t as simple as reading a label.

Typical Dosage: What the Research Says

Health studies often use dosages between 500 mg to 2,000 mg of curcumin extract per day. Most curcumin supplements on the shelf stick to that range. I remember looking at several bottles in a local pharmacy, seeing serving sizes from 450 mg up to around 1,000 mg per capsule. Doctors and researchers rarely recommend going higher than 2,000 mg, since the liver and kidneys have their own limits and the body struggles to absorb curcumin in the first place.

Harvard Medical School and the NIH both warn about taking it on an empty stomach or at very high doses, pointing out that side effects might show up if you go much beyond those research-backed numbers. Those side effects don’t usually cause concern at proper doses, but things like nausea or diarrhea can crop up with heavy use.

Absorption Matters More Than Raw Numbers

Curcumin’s real challenge boils down to absorption. Swallowing even a couple thousand milligrams of plain turmeric powder barely moves the needle in the bloodstream. The body struggles to soak it up efficiently because curcumin passes right through the gut and liver without much of it escaping into active circulation. That’s a bit like pouring water through a sieve.

To get around this problem, supplement companies have started adding black pepper extract — called piperine — which can shoot up absorption by up to 2,000%. Some capsules also pair curcumin with fats or use special delivery forms, turning that yellow powder into a pill the body can actually use. For people like me with stomach sensitivities, it pays to choose supplements that use these improved forms and watch out for heavy fillers or strange additives.

Safety First: Who Should Be Cautious?

Curcumin feels safe to most healthy adults in doses research tests, but it’s always smart to double-check with your doctor. People who take blood thinners, drugs that affect the liver, or have gallbladder problems may see curcumin interact with their medicine. Some of my relatives with heart conditions had to run all their supplements by a physician just to avoid trouble. Pregnant people and those breastfeeding should play it safe and skip self-treatment with curcumin supplements.

Finding the Right Dose

Deciding how much curcumin to take starts with those studies: 500–2,000 mg daily of standardized extract, usually split between morning and night. Quality matters too — look for supplements that give a clear percentage of curcuminoids (the active part) and use trusted third-party testing. Start on the lower side, watch for side effects, and take it with food containing some healthy fats.

Diet helps too. Adding a dash of black pepper to food with turmeric can help turn an ordinary meal into something a little more health-boosting. Supplements can’t do all the work — staying active, eating whole foods, and listening to how your body responds will always pull more weight than any pill.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (1E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,6-diene-3,5-dione |

| Other names |

Curcuma Differoyl Methane Natural Yellow 3 Turmeric Yellow Curcuma longa extract |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɜːr.kjuː.mɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | (1E,6E)-1,7-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)hepta-1,6-diene-3,5-dione |

| Other names |

Curcuma longa Differuloylmethane Turmeric Yellow Natural Yellow 3 |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɜː.kjʊ.mɪn/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 458-37-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1908719 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3962 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL449 |

| ChemSpider | 518644 |

| DrugBank | DB04493 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.013.760 |

| EC Number | EC 1.14.99.14 |

| Gmelin Reference | 11009 |

| KEGG | C06997 |

| MeSH | D003361 |

| PubChem CID | 969516 |

| RTECS number | MI8486000 |

| UNII | JUB39U1Y6B |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| CAS Number | 458-37-7 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1907936 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3962 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL449478 |

| ChemSpider | 538757 |

| DrugBank | DB04124 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 06a1afaf-b8e6-4b94-bd04-e2dd2d0dca50 |

| EC Number | WY7X2JMC42 |

| Gmelin Reference | 71568 |

| KEGG | C06007 |

| MeSH | D000068878 |

| PubChem CID | 969516 |

| RTECS number | VJ7735000 |

| UNII | M8YTC1507T |

| UN number | UN2811 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C21H20O6 |

| Molar mass | 368.38 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow-orange crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.3 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble |

| log P | 3.29 |

| Vapor pressure | 3.3 x 10^-11 mmHg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 8.38 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.5 |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.585 |

| Dipole moment | 6.9355 Debye |

| Chemical formula | C21H20O6 |

| Molar mass | 368.38 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow-orange crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.93 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble |

| log P | 3.29 |

| Vapor pressure | 3.19E-14 mm Hg at 25°C |

| Acidity (pKa) | 8.38 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.38 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | –0.7 × 10⁻⁶ cm³/mol |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.571 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 3.75 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 381.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -795.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -10238.7 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 321.8 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -762.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -12699.8 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A16AX Curcumin |

| ATC code | A16AX Curcumin |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07; Warning; H315, H319, H335 |

| Pictograms | 💊🌿🧡🌱 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use with adequate ventilation. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | 160 °C |

| Autoignition temperature | 334°C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | ORAL (RAT) LD50: > 2,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 2,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | NA343 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 1 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 100–200 mg/day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | Curcumin pictograms: "GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Avoid contact with eyes, skin, and clothing. Wash thoroughly after handling. Use personal protective equipment as required. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-1-0 |

| Flash point | 160°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 400 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): > 2,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Curcumin is "2,000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | Not Listed |

| PEL (Permissible) | 5000 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 500 mg per day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Demethoxycurcumin Bisdemethoxycurcumin Cyclocurcumin Tetrahydrocurcumin Curcuminoids Turmerone |

| Related compounds |

Demethoxycurcumin Bisdemethoxycurcumin Tetrahydrocurcumin |