Copper Gluconate: A Closer Look at Its Journey, Properties, and Future

Historical Development

Copper gluconate’s story begins with the bigger tale of copper’s role in human health and industry. Long before this compound showed up on supplement shelves, doctors and nutritionists understood copper plays a key role for blood, bones, and nerves. Scientists searched for forms of copper that are both bioavailable and gentle on the stomach. Here’s where gluconic acid enters: a product of glucose breakdown, gluconic acid partners up with copper, forming copper gluconate. In the late twentieth century, researchers saw an opening: a supplement stable enough to survive shipping, dissolve in water, and provide a biological nudge where copper levels ran low, such as in cases of copper deficiency or certain inherited disorders. Pharmacists began to trust this salt for dependable dosing, especially as laboratory work in nutrition blossomed.

Product Overview

What stands out in copper gluconate is its dual value: it feeds both human nutrition needs and industrial chemistry. This compound finds itself bottled up for vitamin shelves, incorporated into pet foods, and included in plant fertilizers. Beverage and food technologists use it to fortify products—think of it as insurance for those who struggle to get enough copper from meat, nuts, or leafy greens. Veterinary medicine counts on it, especially as livestock diets shift with industrial agriculture. Copper gluconate powders travel smoothly, dilute quickly, and don't carry metallic aftertaste. That sets it apart from basic copper salts like copper sulfate.

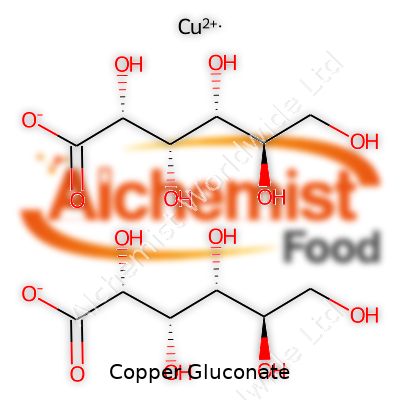

Physical & Chemical Properties

Copper gluconate appears as a pale blue to blue-green powder, with a slightly bitter, metallic taste. It dissolves in water, meaning it starts working fast in the gut. Its solubility separates it from other forms—the copper in this salt becomes available for cellular processes almost as soon as it’s swallowed. The compound melts around 150 °C, and the powder tends to clump in humid conditions. In technical terms, it is made up of one copper ion bonded to two gluconate molecules. It holds the chemical formula C12H22CuO14 and weighs in at 453.84 g/mol. Its stability under light and modest heat helps with storage and shipping, though exposure to high humidity will make it cake or degrade.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Copper gluconate producers pay close attention to purity. Pharmaceutical and food-grade material arrives with copper content of around 12.5% to 13.5% by weight. Impurities like heavy metals, free acids, and arsenic remain under strict thresholds—both for legal reasons and public trust. Packages must list the exact copper content, expiration date, storage conditions, manufacturer identity, and any food allergen cross-contamination risks. Safety labels warn of inhalation risks with dust, and recommend gloves during handling. Both the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversee quality, with packaging designed for traceability and recall management. Product labels often include batch details for easy tracking if something goes wrong.

Preparation Method

Industrial preparation begins with gluconic acid or its sodium salt. A copper(II) source, often copper sulfate, dissolves in water before being slowly added to gluconate under controlled pH and gentle heat. Copper ions swap places with sodium, forming copper gluconate and sodium sulfate. The compound is filtered, dried, and ground into a powder. Aqueous recrystallization ensures any remaining sulfate or unwanted ions get washed out. Final milling creates the fine granules that flow easily for tablet pressing or liquid blending. At every stage, quality control teams keep watch for off-colors, odd smells, or too much particle-size variation, since these signal contamination or decomposition.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Copper gluconate doesn’t just hang around as a supplement. Its ability to act as a mild oxidizer makes it handy in biochemistry, where it can help keep some enzyme reactions running. Where scientists want to create more bioavailable or slower-release forms, they cross-link the gluconate with other organic acids, or swap water for ethanol or propylene glycol to tweak solubility. In industrial cleaning, the copper part breaks down biofilms, while the gluconate keeps copper ions stable against rapid precipitation.

Synonyms & Product Names

You might run into this compound under names like cupric gluconate, copper(II) gluconate, or E578 in European food science. Over-the-counter products may refer to it as “trace mineral copper,” “copper supplement,” or simply “copper tablets.” International suppliers translate the name but keep the same structure. Labels may boast it as a “bioavailable copper source” or “vegan copper complex.”

Safety & Operational Standards

Working with copper gluconate requires personal protective equipment owing to dust risks. Training covers spills, appropriate disposal, and monitoring exposure. Factories hold copper gluconate away from acids and strong oxidizers, since these can speed up copper release and threaten stability or safety. The FDA and EFSA force supplement makers to keep accurate records and recall protocols. Routine audits check for cross-contact with banned substances, and detergent-only lines prevent leftovers from previous products mixing in. Overdosage signals—nausea, vomiting, or liver strain—appear on both consumer and bulk packaging. Veterinary and agricultural use respects local runoff and soil copper limits to keep water supplies uncontaminated.

Application Area

Copper gluconate covers a surprising range of ground. Dietary supplements for people with copper-deficiency anemia lead the pack. Multivitamin blends and energy drinks roll it in, knowing it dissolves swiftly and shows up in blood tests within hours. In animal nutrition, copper gluconate boosts growth and immune response, especially for poultry and swine. Plant fertilizer mixes tap into copper’s disease-fighting roles. Biochemists use it as a trace mineral in microbiological media. Some toothpaste and mouthwash brands add tiny amounts as a plaque-fighter. Beverage companies prefer it to copper sulfate, especially for lower metal-taste and higher shelf-life.

Research & Development

Nutritional science teams keep chasing improved copper formulations, eager to balance maximum absorption with minimum risk. Some lines of investigation focus on combining copper gluconate with zinc or vitamin C, aiming to mimic nature’s blend in whole foods. Others work on encapsulation—microscopic beadlets shield the stomach for slower release and better tolerance. Formulators use copper gluconate for infant formula, adult shakes, and enteral nutrition, always cross-checking for side-effects and metal excess. Medical researchers seek out its anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial abilities, tossing it into experimental gels for wound care, or oral sprays for mucosal healing.

Toxicity Research

Toxicologists pay close attention to copper because, as vital as it is, too much damages the liver and kidneys. Research looks at safe upper limits: for healthy adults, that’s about 10 milligrams of copper per day (total, from all sources). Signs of overdose typically show up first in the gut—nausea, abdominal pain, then wider effects like jaundice or confusion in rare overdose cases. Children and pets run higher risks for toxicity with smaller doses. Long-term animal studies help pin down chronic safety, and regulators demand regular re-evaluation as population diets, supplement use, and agricultural runoff change. Plant and soil researchers track copper gluconate’s environmental fate, looking for signals of copper buildup in crops, water supplies, and distant food chains.

Future Prospects

Looking ahead, the need for reliable copper supplements seems likely to grow as plant-based diets expand and food processing strips out minerals. At the same time, regulators will face louder questions about over-supplementation, especially among consumers stacking single-mineral tablets on top of fortified foods. Scientists keep looking for new uses—better delivery in chronic illnesses, safer livestock nutrition in developing regions, longer-lasting wound dressings for hospitals. Environmental sustainability weighs heavily: every advance in production, purification, and packaging must work in step with waste management and water protection. The next wave of copper gluconate research will likely combine human nutrition, food technology, and ecology in search of solutions where health comes with the smallest environmental sticker price.

What is copper gluconate used for?

The Basics Behind Copper Gluconate

Copper gluconate might not turn heads at the pharmacy, but it plays a quiet and important role in many people’s medicine cabinets and nutrition plans. At its core, this compound delivers copper—a mineral needed in small but critical amounts in the body. Your body uses copper daily for producing red blood cells, keeping nerves healthy, and supporting the immune system.

Why Copper Actually Matters

Copper isn’t a mineral most people think about until there’s a deficiency, but the body quietly relies on it. Without enough copper, iron can’t convert to hemoglobin, and that leaves people feeling fatigued or easily bruised. Too little copper may slow growth in children, dull skin, or even bring nerve problems and immune weakness. In some rare genetic diseases, copper levels can dip dangerously low, and copper gluconate steps in as a supplement.

People tend to overlook how common copper shortfalls can sneak up in certain groups. Strict vegetarians sometimes cut out copper-rich foods like organ meats and shellfish. Folks with heavy alcohol use or issues absorbing nutrients—think Crohn's or celiac disease—are also at risk. For these cases, doctors or dietitians often reach for a copper gluconate supplement as a straightforward fix, because it offers a higher absorption rate than copper oxide and puts less strain on the stomach than other forms.

Everyday Uses in Supplements and Food

A quick stroll down the vitamin aisle shows copper gluconate in multivitamins and mineral blends. Some companies add it to fortified foods—think breakfast cereals and nutrition bars—because copper deficits can undermine their health claims. Sports supplements rarely skip it since strenuous exercise can increase copper needs. Cosmetic brands sometimes sneak trace amounts into topical creams, banking on its role in supporting collagen and elastin in the skin.

Safety and Oversight

Most healthy adults taking daily multivitamins don’t need to worry much about copper gluconate. Still, there’s a line. Too much copper—especially from combined supplements—leads to nausea, cramps, and long-term liver strain. The National Institutes of Health caps adult daily copper intake at 10 milligrams. Copper poisoning remains rare, but some older water pipes still leach copper into drinking water, and layering extra supplements on top can cause trouble. So doctors usually run blood tests before approving high-dose supplements, especially in kids or anyone with kidney or liver concerns.

Addressing the Root Problem

Copper gluconate fills real gaps but acts best as a tool, not a crutch. A steady diet brings copper naturally from nuts, beans, leafy greens, and seafood, so most U.S. diets cover it without fuss. For vulnerable groups—infants with genetic aciduria, patients on long-term IV feeding, people on restrictive diets—working with a nutritionist makes sense. Food policy experts also watch deficiency trends and recommend fortification where it makes sense, so nobody gets left looking for copper in a bottle.

Quality and Trust in Supplements

People want to feel confident that what they're taking matches the label, delivers safe dosages, and hasn’t been contaminated. That’s why I look for products tested by third parties, like USP or NSF, and check that brands share their sourcing and quality control practices. Trust in a supplement grows from transparency and solid science.

Is copper gluconate safe to take as a supplement?

Looking at Copper Gluconate and Its Role

Standing in the supplement aisle, the little bottles promise a fix for nearly everything. Copper gluconate pops up as a solution for anyone worried about low copper. This trace mineral matters. Without enough, the body struggles with making red blood cells, keeping immune defenses strong, and supporting energy production. Some foods, like oysters, nuts, and seeds, pack copper in good amounts, but diets today sometimes cut these out. Suddenly, there’s a market for easy pills.

What Science Says About Copper Gluconate

Copper gluconate lands on the list of compounds used to boost the body’s copper storage. The U.S. National Institutes of Health lays down a daily recommended intake of about 0.9 mg for adults. Most people eating a varied diet reach this mark without issues. Supplements like copper gluconate push the numbers up much faster, and in higher doses, copper can cross from essential to harmful. The body does not flush excess copper out quickly. Instead, it builds up, sometimes leading to symptoms like stomach pain, nausea, or even liver damage.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration sees copper gluconate as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) when used in food. This covers trace amounts, not the much higher dosages found in supplements. Too much copper over time can tangle with zinc absorption, hurting immunity and overall health. I remember reading case reports during my nutrition training about people who unknowingly doubled up on copper—vitamin pills, protein shakes, foods fortified with copper—all thinking “a bit more can’t hurt.” The result? Health emergencies in the ER, long recoveries, and confusion over why something “natural” went so wrong.

Why the Form You Choose Matters

Copper comes in several forms for supplements. Copper gluconate dissolves well and absorbs slightly better than copper oxide, another common type. Still, these differences do not add up to much if someone already gets enough copper from meals. Multivitamin makers often add it simply because it sounds reassuring on the label, not because most folks need extra.

Risks of Overdoing It

The upper intake level for adults lands at 10 mg per day. Staying below that mark prevents problems, but small children and those with genetic conditions like Wilson’s disease can’t handle even typical amounts. Anyone with liver problems or a history of copper buildup needs to tread carefully. Copper toxicity doesn’t always scream for attention. Often, it creeps in with joint aches, weak muscles, or odd mood changes. Blood tests can show a problem, but symptoms tell the real story—and sometimes by then, damage is done.

Smarter Supplement Choices

A diet built around vegetables, whole grains, and seeds covers copper needs for most adults. Blood work at the doctor’s office gives the best picture of mineral balance. Before starting any new supplement, including copper gluconate, getting advice from a pharmacist or health provider can sidestep most risks and save money. Supplements fill gaps when real food cannot, but they work best when guided by real need—never just a guess from a label.

What Can Be Done

More Americans could benefit from better food labeling and education. A little talk with a nutrition specialist can prevent confusion. For those thinking about taking copper gluconate, reviewing what comes from food first takes priority. Watching for duplicate minerals in shakes, bars, and vitamins helps avoid the pitfalls of over-supplementing. Trusting in balanced meals and honest assessments beats riding the supplement roller coaster every time.

What are the health benefits of copper gluconate?

Why Copper Matters for Health

People have been talking about copper as an essential nutrient for a long time. As a trace mineral, copper shows up in dozens of roles inside the body—think energy production, immune support, joint health, even keeping nerves firing like they should. What gets overlooked is how copper enters everyday diets, and what happens if it doesn’t. Most folks get copper through a decent diet, but gaps can show up, especially with heavily processed foods or special diets. Here’s where copper gluconate steps in.

What Makes Copper Gluconate Useful

Copper gluconate lands on supplement shelves because it gives a reliable and easily absorbed form of copper. Its chemical structure means the body can use it without much trouble, so more copper ends up in cells where it’s needed. Some studies point out that more bioavailable copper means better results, especially for those with low intake or higher needs.

The Body’s Relationship with Copper

Enzymes depend on copper. Superoxide dismutase (SOD), for example, cleans up harmful molecules before they do serious damage to tissues and DNA. Without enough copper, this antioxidant line of defense stumbles. The same story plays out with iron metabolism—copper helps iron move out of storage and into new red blood cells. Even small dips in copper can lead to fatigue, low immunity, or problems in the nervous system.

Addressing Deficiency Risks

People on strict diets, like vegans or those with digestive disorders, might not get enough copper. Older adults or those using a lot of zinc supplements might unintentionally crowd out copper, too. In these cases, copper gluconate can close the gap. It doesn’t take much—a typical dose shows up around 2 mg per day, which fits within recommended limits and avoids the risks that come from too much copper (which can harm the liver over time).

Immune and Skin Benefits

Research shows copper plays a huge role in immune cell development. Low copper makes the immune system work less effectively. Some experts connect adequate copper to better recovery from illness and improved wound healing. With skin, copper supports collagen production. I noticed after fixing my own mild copper deficiency (thanks to a nutritionist and a supplement), my skin lost its dull look and cuts closed up faster.

Mental Health and Nerve Function

Copper also influences the way the brain and nerves talk to each other. Neurotransmitters—chemicals like dopamine and norepinephrine—rely on copper for their formation. Kids and adults with copper deficiencies are more likely to have attention or coordination problems. While more research keeps coming out, early signs suggest the right amount of supplemental copper gluconate might help support mental sharpness and balance mood in some people.

What the Science Says

Trusted research teams, including the National Institutes of Health, stress the careful balance of micronutrients like copper. Supplementing with copper gluconate works best for people who can confirm low copper with their healthcare provider. Lab testing—combined with food tracking—gives a real answer instead of guessing. It’s important to remember that more isn’t always better. Food sources like nuts, shellfish, beans, and seeds offer copper in safe, slow-release doses. Supplements like copper gluconate fill the gaps, not pound the system with too much all at once.

Using Copper Wisely

Taking copper gluconate should tie back to some real need—a known deficiency or a unique health situation. Trustworthy advice from a registered dietitian or physician helps make sense of lab results and tells you if copper gluconate is the right tool. Watch for interactions with other minerals; zinc and iron can compete with copper for absorption, so timing supplements differently can make a difference.

What is the recommended dosage of copper gluconate?

Figuring out how much copper gluconate to take isn’t always as simple as reading a number on a supplement bottle. Growing up in a rural area with well water, I saw a neighbor experience copper toxicity. He thought if a little copper helped the body, then a lot would be even better. He was wrong. I learned early that the body treats minerals with a mix of need and caution. Copper isn’t just a trace mineral, it’s a Goldilocks mineral: you need enough, but not too much.

Recommended Intake and Where to Find Guidance

The Food and Nutrition Board of the Institute of Medicine puts the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for copper at about 900 micrograms per day for most healthy adults. Copper gluconate serves as one of the more readily available forms of supplemental copper, but the actual amount of copper you get from it is less than the weight you see on the label. Each 1 mg of copper gluconate contains about 14% elemental copper. That means a standard 2 mg tablet provides only about 0.28 mg, or 280 micrograms, of true copper.

People often come across copper as an ingredient in multivitamins or as a stand-alone supplement in doses ranging from 1 to 3 mg. The key: most folks already get enough copper through regular meals. Whole grains, shellfish, nuts, seeds, leafy greens, and even dark chocolate serve up copper by the bite. Jumping to supplements without a clear medical need can tip the balance in the wrong way.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Copper plays a role in making energy, forming red blood cells, and keeping nerves healthy. The catch: the body can’t easily dump out extra copper. High intakes—over 10 mg of copper per day—can damage the liver or lead to symptoms like stomach upset, faintness, or even mental changes. The National Institutes of Health set the upper intake limit at 10 mg per day for adults, which includes copper from food and supplements combined. I’ve come across cases where people developed problems just from high doses in supplements, not from a heavy hand with the peanut butter.

Why Dose Matters

Doctors rarely recommend copper supplements unless a true deficiency shows up. Wilson’s disease, Menkes disease, or problems with the gut that cut down copper absorption change the picture, but they are rare. Blood tests guide these situations. In most cases, boosting dietary sources makes more sense than pills. Supplements tempt people seeking an edge in energy or immunity, but science doesn’t back those quick fixes for the average person.

Here’s a practical guideline: unless a healthcare provider suggests otherwise, leaning on real food—greens, legumes, nuts, seeds, a little seafood—safely covers copper needs for almost everyone. Supplements sometimes help when diet falls short, as in certain chronic illnesses or strict vegan diets without variety, but getting directions from a medical professional makes a real difference. Self-dosing risks harm, especially as the signs of mild copper excess sneak up slowly.

Smart Supplement Strategies

Talking with a doctor before starting copper gluconate ensures you don’t stack up more risk than reward. If your diet misses several copper sources, labs and a well-informed recommendation beat guesswork. For most people, the right copper dosage slips naturally into the day through balanced meals instead of a pill.

Are there any side effects of taking copper gluconate?

Copper: From Diet to Supplement

For most people, getting enough copper through food rarely feels like a problem. Foods like nuts, seeds, whole grains, and beans handle the job just fine. Even tap water sometimes brings a bit along. But the story changes when you start reaching for copper gluconate on pharmacy shelves. Copper is essential, for sure, playing a role in making red blood cells and keeping nerves happy. So taking extra in the form of a supplement can seem tempting, especially after scrolling through articles about micronutrient gaps or immunity supports. Still, it’s worth paying attention to what science and everyday experience say about side effects before you toss another pill into your wellness routine.

What Happens With Too Much Copper?

Copper isn’t like vitamin C where extra just passes through. The body can only handle so much, so taking too much copper gluconate builds up trouble instead of health. Some folks notice nausea, a metallic taste in the mouth, or even abdominal cramps not long after taking it. Kids, in particular, show a sensitivity to small increases—possibly vomiting or diarrhea, leading parents to scramble and question if the supplement was worth it. Headaches sometimes follow. Color changes, like a yellowish skin tone or dark urine, might show up if copper overload gets severe. In rare cases, there’s a risk for liver problems, and that’s where things get dangerous fast.

Who’s Most at Risk?

People with conditions like Wilson’s disease don’t process copper right. Their bodies store copper instead of getting rid of it, so even a small supplement pushes things toward toxic levels. For folks with a healthy liver and kidneys, small doses rarely cause serious trouble but usually aren’t necessary unless a doctor finds you genuinely deficient. Anyone taking zinc supplements also faces a balancing act, since too much copper or zinc can knock the other off track.

Why the Hype Exceeds Reality

Health trends travel fast online. Some influencers praise copper gluconate for everything from more energy to better skin. In practice, published studies show these benefits only show up when real deficiency exists—which is actually rare. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for copper for adults sits at about 900 micrograms daily. Multivitamins cover most needs, and food covers the rest. It’s easy to get convinced by glowing testimonials, but side effects don’t always get a spotlight in those posts.

Looking for Safer Options

Most folks want to do right by their bodies, not hurt themselves trying. Instead of loading up on supplements, it’s smarter to get bloodwork done to actually check copper status before buying any pills. Medical professionals have seen more problems from excess copper than from copper shortages. Reading ingredient lists helps, since some fortified foods or even drinking water can push someone over the safe amount without them realizing it.

Smart Steps Forward

Supplements work best when they fix a gap that actually exists. Chasing wellness by adding copper gluconate without clear need or direction can backfire, leading to nausea, headaches, and worse. Safe health habits always start with talking to a qualified professional and relying on food sources whenever possible. Trends might come and go, but your body’s need for balance sticks around.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Copper;2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate |

| Other names |

Copper, bis(D-gluconato-O1,O2)-, (T-4)- Copper(II) gluconate Gluconic acid, copper(2+) salt Cupric gluconate |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒpər ˈɡluːkəneɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Copper(II) bis[(2R,3S,4R,5R)-2,3,4,5,6-pentahydroxyhexanoate] |

| Other names |

Cupric gluconate Copper(II) gluconate Gluconic acid, copper(2+) salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkɒp.ər ˈɡluː.kə.neɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 299-28-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3596819 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3159 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201358 |

| ChemSpider | 71408 |

| DrugBank | DB11267 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03a92d18-e831-438b-8b1b-bcddedc41e71 |

| EC Number | EC 231-484-3 |

| Gmelin Reference | 57480 |

| KEGG | C01764 |

| MeSH | D003789 |

| PubChem CID | 24808152 |

| RTECS number | LZ2600000 |

| UNII | U4FWB9154K |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 299-28-5 |

| Beilstein Reference | 392924 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:3159 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201531 |

| ChemSpider | 72357 |

| DrugBank | DB11129 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 03-2119957877-20-0000 |

| EC Number | E578 |

| Gmelin Reference | 21268 |

| KEGG | C01601 |

| MeSH | D015234 |

| PubChem CID | 24856513 |

| RTECS number | GL7890000 |

| UNII | 7LKT8L9455 |

| UN number | “UN3077” |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID7020372 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C12H22CuO14 |

| Molar mass | 453.84 g/mol |

| Appearance | Light blue or bluish-green crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 0.8 g/cm3 |

| Solubility in water | 16 g/100 mL (20 °C) |

| log P | -1.35 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.7 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.5 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | -9.63 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.57 |

| Viscosity | Viscous liquid |

| Dipole moment | 0.00 D |

| Chemical formula | C12H22CuO14 |

| Molar mass | 453.84 g/mol |

| Appearance | Light blue or bluish-green crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | Density: 0.8 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble in water |

| log P | -2.6 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.3 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 11.5 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.59 |

| Dipole moment | 3.34 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 437.1 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1676.6 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 440.1 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1884.11 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -3627 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A12CX01 |

| ATC code | A12CB02 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed; may cause irritation to eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Hazard statements | H302: Harmful if swallowed. |

| Precautionary statements | P264: Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P270: Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. P301+P312: IF SWALLOWED: Call a POISON CENTER or doctor/physician if you feel unwell. P330: Rinse mouth. |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Copper Gluconate: "Cu Gluconate LD50 (oral, rat): 300 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | WA7125000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 1 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 1.6 mg (as copper) per day |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | IDLH: 100 mg/m³ |

| Main hazards | Harmful if swallowed. Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS09 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | Hazard statements: Harmful if swallowed. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 93.3 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 4,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Copper Gluconate: "Copper gluconate LD50 (oral, rat): 1000 mg/kg |

| NIOSH | Not Established |

| PEL (Permissible) | 1 mg/m³ |

| REL (Recommended) | 1.50 mg |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | IDLH: Not established |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Copper(II) sulfate Copper(II) chloride Copper(II) acetate Copper(II) carbonate |

| Related compounds |

Calcium gluconate Iron(II) gluconate Magnesium gluconate Manganese(II) gluconate Potassium gluconate Sodium gluconate Zinc gluconate |