Citric Acid: A Deep-Dive Commentary

Historical Development

Citric acid traces its story all the way back to the 8th century, where Persian and Arab alchemists explored sour fruit juices for medicinal use. By the late 1700s, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele crystallized the substance from lemon juice, opening doors to industrial extraction. Through the 1800s, Italy’s lemon groves powered most of the world’s supply. After World War I, the Italian harvest couldn’t keep up with demand or keep prices stable, so researchers looked for something more reliable. American food chemists learned that the mold Aspergillus niger produced this acid on sugar. Fermentation won the day, cutting production costs and letting citric acid reach everything from soft drinks to textiles. Instead of tracking harvests, the world embraced a stable supply chain built around biotechnology.

Product Overview

Citric acid, known for its tart bite, pops up in kitchens, labs, and factories everywhere. It’s more than a flavor booster in soda or gummy worms. Chefs count on it as a preservative, while soap makers look to it for balancing pH. Food processors dump it into energy drinks, cheese spreads, and canned vegetables. Walk into most cleaning aisles and you’re likely touching it in detergents or specialty descalers. Medical pros value it in anticoagulant solutions. The versatility stems from how easily its molecules interact with metals, proteins, and fats. As someone who grabs lemony snacks during road trips, I rarely think about the work done by this compound behind the scenes. Its reach keeps expanding, showing up in ways most people don’t realize.

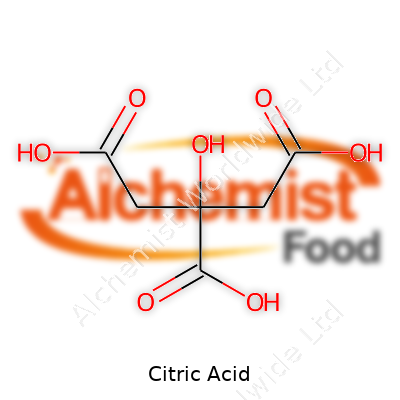

Physical & Chemical Properties

Pure citric acid looks like a white, odorless powder with a sharp, sour taste that twists your tongue. Most folks notice the crystalline granules dissolve cleanly in water. The chemical formula C₆H₈O₇ points to three carboxyl groups, which give it that punchy acidic taste and make it a champion at binding metals. Its melting point hovers near 153°C, and it breaks down in the heat, which matters in certain food and pharmaceutical processes. It absorbs moisture from air, making tight packaging essential for bulk storage. Citric acid isn’t flammable under typical storage or usage conditions. If you spill a handful on the kitchen counter, it cleans up with water, but you don’t want it sitting there too long; its acidity may eat into softer materials or discolor the surface.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Producers list citric acid by more than just its name—labels display purity, moisture level, and granulometry, especially for pharmaceutical or food-grade batches. Industry standards set the minimum purity at 99.5% for food use, a strict line that helps avoid contamination. Particle size ranges from fine powders to larger crystalline granules, dialing in different dissolving rates—a detail manufacturers can’t ignore. In the United States, the Food Chemicals Codex sets the mark. Globally, the E330 label points to it on ingredient panels. Several authorities, including the FDA and EFSA, set rules on maximum usage levels. Attention to labeling ensures supply chains avoid confusion or mix-ups in shipment, especially when companies route their orders across continents. In my work with quality control teams, I’ve seen how tight specs prevent massive product recalls and keep customers happy.

Preparation Method

Nearly all citric acid starts its journey in a fermentation vat, where factories grow Aspergillus niger on sugars from molasses or corn syrup. Workers feed the mold and encourage it to churn out citric acid into the broth. Filtration removes the mold, while lime rounds up impurities in the liquid. Once the liquid has settled, technicians add sulfuric acid to liberate the citric acid from its calcium salt. After careful evaporation, crystallization delivers the final powder or granules. Every step has safeguards: temperature swings, pH levels, and contamination risks. The method isn’t much different than crafting key antibiotics or vitamins; the challenge lies in keeping yields high with minimal waste. Years ago, I visited a bioprocessing facility where the steady hum sounded like any modern kitchen, though thousands of liters bubbled at once instead of just one pot on the stove.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Citric acid’s structure offers endless routes for modification. It chelates metals, forming stable complexes—an ability valued by both water softener manufacturers and biochemists. In foods, it slows browning by capturing iron and copper ions. Mix it with baking soda and you get a fizzing eruption, a crowd-pleaser in both elementary school volcano projects and the pharmaceutical world, where effervescence masks bitter medicines. Citric acid acts as a precursor for more complex molecules like citrate esters (plasticizers for flexible plastics) or non-toxic cleaning agents. Under heat and water, it can dehydrate into aconitic acid. Biochemists know its skeleton as a star player in the Krebs cycle, making it central to life as much as to cleaning grime off a sink.

Synonyms & Product Names

On ingredient labels, citric acid pops up with names like E330, 2-Hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid, or Sour Salt. Sometimes brands tout it under catchy trade names for specialty applications—Batco, Citroflex, or Trisodium Citrate (when neutralized). Though chemists keep it straight with IUPAC names, food technologists pick up whatever their market recognizes, falling in line with local labeling laws. The variety can confuse consumers, who may not connect “citric acid” in a drink to “trisodium citrate” in a bag of cheese powder. The jumble of product names sometimes hides a cleaner, simple truth about what’s landing on the kitchen table or bath tile.

Safety & Operational Standards

Folks trust citric acid because extensive testing backs its safety record. Regulatory panels in the US, EU, and Asia have cleared it for food and beverage use, providing strict limits to cut any risk of overuse. For workers handling the pure chemical, protocols call for gloves, face shields, and dust control—chronic exposure can sting skin or eyes, and inhaling a large amount of dust is never a good day at work. In factories, safety engineers train workers to handle accidental spills—react quickly with ventilation and lots of water. In the consumer realm, ordinary exposure isn’t a hazard, but overindulgence in sour candies or drinks might leave your mouth sore. I read through stacks of incident reports over the past decade—problems rarely stem from the acid itself, more often from ignoring good basic handling habits.

Application Area

Demand for citric acid keeps growing in foods and beverages, where it balances flavors, boosts freshness, and lowers spoilage risk. Soft drink makers cannot part with it; neither can cheese factories or candy kitchens. Cleaning companies rely on its limescale-fighting power to keep appliances and surfaces gleaming. Textile and leather workers use it for dye-fixing and neutralizing alkaline soaps. Pharmaceutical giants trust the acid to adjust the pH in injectable medicines or dental products. Water treatment plants pour it into pipes to curb metal buildup and corrosion. Even pet food processors look to it as a natural preservative. A walk through any decent supermarket or home goods aisle turns up a dozen products where citric acid is playing a crucial, if mostly invisible, support role.

Research & Development

Labs across the world keep tinkering with both the production and use of citric acid. Microbiologists work on tweaking Aspergillus strains to pump out more acid from cheaper or greener feedstocks. Researchers try to swap in agricultural byproducts otherwise destined for landfills—wheat straw, sugarcane bagasse, or even coffee pulp—hoping to push costs lower and serve circular economy goals. Chemists play with the acid’s backbone to develop new biodegradable plastics or highly specific cleaning formulas. Health scientists run studies to confirm that even long-term, frequent exposure through food and therapeutics causes few issues. The drive to “green up” industrial chemistry turns the attention to safer, waste-minimizing processes, shrinking the environmental load tied to large-scale use.

Toxicity Research

Decades of toxicology work conclude that citric acid is safe for most people, barring rare cases of severe allergy or specific metabolic disorders like citrullinemia. High doses irritate tissues—swishing pure powder in your mouth feels like a dental nightmare—but foods contain it at much lower concentrations, making day-to-day risk minimal. Animal studies, cell cultures, and chronic exposure trials stack up to the same verdict: For the population at large, citric acid doesn’t build up in organs, doesn’t trigger cancers, and exits the body painlessly through everyday metabolic cycles. Regulatory agencies revisit these numbers over and over, driven by new research or public concern. Medical experts keep a cautious eye on new food products for excessive sour spike, especially with kids, but so far the track record holds steady.

Future Prospects

Citric acid’s future looks bright, especially as consumer pressure rises for clean-label, natural products. Ingredient buyers for vegan and organic foods demand fermentative sources that side-step synthetic additives. Water treatment plants fight scaling as populations in urban regions explode—citric acid’s non-toxic profile makes it a favored option. Research walks toward biodegradable polymers based on its backbone, cutting the environmental costs of legacy plastics. Designers of smart delivery systems in medicine look for ways to embed citric acid that release only under certain conditions, pushing the boundaries of personalized care. With climate change forcing a rethink on crop use and waste, producers look at sidestream raw materials to stretch resources. I’ve talked to innovation teams in several companies chasing new patents using citric acid as a starting block for everything from bio-based coatings to specialty cleansers. Every new use seems built on the reliable, well-tested chemistry first noticed in a lemon, now engineered through a global web of labs and factories.

What is citric acid used for?

A Handy Helper in the Kitchen

Citric acid crops up almost everywhere—just look at a can of tomatoes, bag of gummy bears, or even that fizzy soft drink in the fridge. Most folks recognize a hint of tartness without even knowing citric acid is at work. Found naturally in citrus fruits like lemons and limes, manufacturers now make most of it by fermenting sugars with a special mold. Food companies rely on citric acid to brighten flavors and cut through sweetness, give that sharp note in sour candies, or keep cut fruit from turning brown. I’ve seen cooks sprinkle a little in home canning projects to raise acidity and keep things safe from bacteria. For people who care about what they eat, understanding ingredient lists makes all the difference, and citric acid pops up more often than expected.

Beyond Food: Household Cleaning

Anyone who cleans kitchens or bathrooms runs into stubborn stains and limescale. Citric acid’s natural sourness comes from its ability to grab onto minerals, so it turns up in cleaning products aimed at descaling kettles, coffee makers, and dishwashers. I’ve dumped a couple of spoonfuls into my kettle before, swished it around, rinsed, and wound up with spotless results. Unlike strong-smelling bleach, citric acid does the job without choking fumes. For folks who prefer to stay away from harsh chemicals, it offers a gentler, safer way to keep things clean.

Supporting Health and Safety

Pharmacies stock citric acid for more than just taste. In some medicines, it balances acidity or helps preserve freshness. Anyone who’s wrestled with hard water stains on glass or inside a coffee maker will find it handy. Medical professionals sometimes use it in solutions to stabilize certain medications or help deliver minerals the body needs. Its low toxicity means it’s generally safe for regular household use. Kids with allergies to common food preservatives sometimes handle citric acid better—something worried parents might want to check with a doctor or dietitian. Allergic reactions are rare, but folks should always read ingredient lists, especially if sensitive.

Solving Problems in Everyday Life

Food waste remains a stubborn problem, with many families tossing out fresh fruit and vegetables due to browning or spoilage. Sprinkling a touch of citric acid on cut produce can stall the browning process, extending its shelf life. I’ve seen this at play in lunchboxes—the kids’ apple slices stay white until school ends. In the garden, it sometimes comes in handy for adjusting soil pH, mainly for plants that like things a bit more acidic. There’s a learning curve, and gardeners must take care not to disrupt the natural balance.

The Need for Honest Labels

Citric acid might sound industrial, but its uses shape much of what’s in pantries and cleaning cupboards. Honest, clear labeling in the food and cleaning industries helps shoppers make informed choices. People deserve to know what goes into their bodies and homes. Companies can support this by providing straightforward information about ingredient sources and their reasons for inclusion. More education for consumers builds trust.

Paying Attention to the Small Print

So many products rely on citric acid, from salad dressings to dishwasher tablets. Even though it rarely causes harm and has a solid track record, the practice of checking labels and questioning contents matters. For household cleaning, avoiding overuse and respecting dosage guidelines keeps homes safe and avoids unnecessary pollution. In the kitchen, using it as intended means better shelf life and flavor. Everyone stands to benefit from knowing more about this sour little powder hiding in plain sight.

Is citric acid safe to consume?

Everyday Encounters With Citric Acid

Open a box of lemon-flavored candies or check the label on your favorite fizzy drink — you’ll often spot citric acid in the fine print. I grew up with it in my family kitchen. My mother squeezed fresh lemons over salads, and my dad, a biologist, explained the sour edge came from this natural compound found in citrus fruits. Today, food makers extract citric acid mostly from black mold (Aspergillus niger) due to convenience and cost; the shelf life and sharp tang keep sodas snappy and jams spreadable.

Chemistry and Function at the Table

Chemically, citric acid isn’t some foreign invader. The body produces small amounts during metabolism, which means every cell sees it day in and day out. In food, it makes flavors pop, curbs spoilage, and curdles the milk needed for certain cheeses. It isn't just in treats and drinks—jars of pickles, canned vegetables, and some nut-based cheeses depend on citric acid to balance flavor and safety.

Scientific Understanding of Citric Acid’s Safety

Researchers have looked at citric acid intake for decades. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration tags it as “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS). Studies back up this assessment, showing that healthy livers break it down with little fuss. People have used it in food for more than a century, with little evidence pointing to harm from normal amounts in diets. One survey by the European Food Safety Authority found no health risks tied to typical consumption levels in children or adults.

Concerns that Pop Up

Concerns rarely stem from citric acid itself. Some folks with rare allergies might feel a tingle if they eat too many sour candies, but this is less about citric acid and more about an underlying sensitivity. Tooth enamel can suffer with constant exposure to acidic foods — juice sippers and soda lovers often see their dentists about wear and tear, not because of citric acid specifically but the sour pH in general.

Processed citric acid comes from molds, leading some to wonder about possible reactions. Researchers checked these fears, but the level of residual mold protein in the final ingredient falls below levels known to provoke allergies in most people. Still, doctors pay close attention for patients who report mysterious symptoms after eating heavily processed foods. I’ve noticed, through years of reading food safety studies and talking with nutritionists, that digestion problems tied to citric acid almost always involve other food components or underlying sensitivities.

Practical Approaches and Personal Choices

For most people, moderate citric acid in foods causes no trouble at all. If you’re worried about sour candies hurting your teeth, drink water afterward and brush up—a simple fix dentists recommend. If you suspect a reaction to anything in your food, working with a healthcare provider helps pinpoint if citric acid plays a role.

We depend on the sour snap of citric acid to make food enjoyable and safe. Good science and decades of use give little reason to fear its place in your pantry or at your table.

Is citric acid natural or artificial?

The Origins of Citric Acid

Citric acid sounds harmless, even wholesome, perhaps because our minds go to oranges or lemons when we hear those words. In my kitchen, lemon juice adds that sharp flavor to tea or fish, and I’ve always thought of it as a staple from nature. Few items in the grocery store seem as ordinary as citric acid, whether it’s on the ingredient list in soda, canned tomatoes, or a bag of sour candy. But peel back the label and the story behind how most citric acid gets into our food often catches people by surprise.

Lemons or Fungi: How Citric Acid is Made Now

People used to think all citric acid came from fresh citrus fruit, just squeezed out and dried. Originally, it was easy to get citric acid this way. Lemons, limes, oranges—each one packed with the stuff. In 1917, though, a scientist named James Currie figured out that a fungus, Aspergillus niger, churns out citric acid like nobody’s business when it feeds on cheap sugar. Massive growth of the food industry made this fungal process the go-to method, since squeezing tons of lemons for every soft drink or candy didn’t stack up economically.

Now, nearly all commercial citric acid comes from Aspergillus niger grown on starchy crops such as corn. Manufacturers feed the fungus a sugar solution, then filter and dry out what’s left until only white citric acid powder remains. This process slashed prices and met growing demand but changed the link between citric acid and citrus fruit.

Is It Still Natural?

The answer gets murky here. Legal definitions of “natural” in food labeling run all over the map. To most folks, natural means straight from a plant or mineral, mostly unchanged—think apple slices, not apple-flavored candy. Chemically, the citric acid from Aspergillus looks exactly like that from a lemon. Your body can’t tell the difference. But the production method—a fungus in a vat, gobbling up corn syrup—feels industrial, not orchard-fresh.

Some health advocates question the fungus-derived process. Signal to folks allergic to mold: tiny traces of leftover proteins may cause problems. Others worry about the origin of the sugar, since genetically modified corn often serves as the feedstock. Not much evidence points to direct harm from the citric acid itself, and food safety authorities generally nod their approval. It’s the perception that a “natural” label has drifted far from what shoppers picture that has fueled plenty of the debate.

Why This Matters

Food labels aren’t always clear. I’ve bumped into shoppers at the store who tell me they avoid “artificial” additives wherever they can, but every shelf carries boxes and jars with citric acid in the fine print. Full ingredient stories would help folks make their own choices, especially people avoiding allergies or following special diets.

If companies explained whether their citric acid comes from citrus or a fermenter, the debate over natural versus artificial wouldn’t seem so mysterious. There’s room for regulatory bodies and manufacturers to step up with clearer definitions, so people who want real fruit-derived acids can seek them out—and those comfortable with fungal fermentation can make that call, too.

For now, anyone searching for true “natural” citric acid faces a tough task, unless they squeeze lemons at home. Grocery store powder almost always comes from a lab, not a grove. That doesn’t turn it into a dangerous chemical—it just means the food system runs on science as much as sunshine. Knowing that helps me remember that reading ingredient lists is only the start of making smart food choices.

Can citric acid be used for cleaning?

Breaking Down Citric Acid’s Role in Cleaning

Growing up, my kitchen always smelled like lemons on weekends. My grandmother would scrub everything with what she called “natural cleaner.” Later, I learned it wasn’t just lemon juice, but a mix loaded with citric acid. She trusted it to cut through stains and hard water spots before reaching for anything else. Citric acid, often found in citrus fruits like lemons and limes, packs a punch against mineral deposits and grime.

In recent years, a lot of folks have started searching for simpler cleaning solutions. The store shelves reflect this shift, pushing chemical-free brands front and center. At the core of that movement sits citric acid. With research showing its ability to tackle limescale and dissolve rust, citric acid stands out because it’s not just safe for the environment; it leaves behind no toxic residue.

Citric Acid in Everyday Cleaning

The real proof shows up in regular use. Hard water stains make faucets look old and cloudy, but just a tablespoon of citric acid dissolved in warm water often restores the shine. Pouring that mix into a kettle with stubborn deposits cleans it better than most descalers. Washing machines and dishwashers, which attract limescale around hidden parts, also respond well to citric acid cycles. This isn’t snake oil. The acid binds to mineral buildups and breaks them down so they rinse away.

Research from the International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology explains that citric acid can even handle certain bacteria. It’s not as aggressive as heavy-duty disinfectants, but it will sanitize counters and sinks in everyday use. Families with young kids or pets often look for alternatives that won’t linger on surfaces or drift into little mouths. That’s a real reason why citric acid outpaces bleach for things like high chairs or fridge shelves.

Limitations and Cautions

Nothing comes without its downsides. Acid can wear away delicate stone or cause pitting in metals. Marble and granite don’t like it, and some dishware with metallic edges or finishes might tarnish. Covering your bases—test on a small spot and rinse thoroughly—saves money and stress later.

Another reality: citric acid doesn’t wipe out all viruses or handle mold problems deeply rooted in grout. For deep cleaning mold or killing viruses like norovirus, citric acid won’t match the punch of commercial disinfectants. Matching the tool with the job keeps expectations realistic.

How to Use Citric Acid Safely and Effectively

Practical use always comes down to measurement and common sense. Store-bought powders offer easy mixing in warm water. A spray bottle filled with that solution cleans most kitchen and bathroom surfaces. Avoid direct contact with eyes or open skin, and don’t breathe in the powder directly—it can irritate the throat or eyes. Wearing simple gloves, especially for people with sensitive skin, adds a layer of protection. Rinse containers and surfaces if food will touch them after cleaning.

Households worried about the environmental impact of chemical cleaners find citric acid meets both safety and performance needs. As more evidence piles up supporting its use—not just from age-old tradition but also new research from reputable science—citric acid stands as a practical, effective, and gentle cleaning solution for most homes. Swapping the harsh stuff for a lemon-derived powder can make chores safer, easier, and a little brighter.

Does citric acid have any side effects?

Citric Acid Beyond the Lemon

Open a jar of pickles, a can of soda, or that bag of sour gummies, and chances are citric acid is on the label. It's more than a kitchen staple. Manufacturers use it to add a tang or keep food tasting fresh. Some folks even swear by its cleaning power around the house. Citric acid comes from citrus fruits and through fermentation processes using certain kinds of fungi. The story doesn’t end at its handy uses, though. Sometimes everyday ingredients raise questions, especially when they show up everywhere.

Potential Side Effects: Real Stories Behind the Science

No one expects a sprinkle of lemon juice to cause trouble. For most healthy people, small amounts of citric acid as found in food won’t spark problems. For folks like me with a love of sour candy, moderation keeps things comfortable. Eating too many sour treats at one time irritates my mouth and tongue. There’s science behind that: citric acid’s low pH makes the inside of the mouth sensitive, even raw and sore if overdone. A study in the Journal of the American Dental Association highlights how repeated exposure to acidic products weakens tooth enamel, leading to erosion and long-term dental sensitivity.

For people sensitive to ingredients or managing allergies, citric acid sometimes becomes a point of concern. There’s a difference between naturally occurring citric acid and what you find in packaged foods—manufacturers often use a mold called Aspergillus niger to produce it. The FDA considers this safe, but there have been isolated reports of reactions in people sensitive to molds, leading to symptoms like stomach pain or rashes. Still, these cases are rare. If you have a diagnosed mold allergy or unexplained rashes after eating processed foods, talking to your doctor can help pinpoint triggers.

Digestive and Skin Irritation

Stomach upset isn’t common for most folks, but if you’re prone to acid reflux, citric acid can add fuel to the fire. For a friend who deals with heartburn, vinegary dressings or lemony sauces leave her regretting her meal. Acidic foods already top the list of foods to watch for people with GERD or ulcers. Citric acid, even in small amounts, sometimes brings the heat. Those with sensitive digestive tracts find relief by checking labels and reminding themselves that fresh can sometimes be easier than shelf-stable.

Outside the kitchen, citric acid shows up in skincare products as an exfoliant or preservative. Personal experience taught me to always patch-test new lotions. Even mild amounts sometimes bothered my skin, causing redness or tightness, especially if used too often. Dermatologists point out that acids can disrupt natural pH balance, and overstimulation leaves skin feeling angry instead of refreshed. Sensitive skin types do best with gentle use and by looking out for high concentrations.

Practical Steps and Smart Choices

Too much of anything rarely ends well. To guard against tooth erosion, dentists recommend waiting at least 30 minutes before brushing teeth after eating acidic foods, letting enamel recover. Rinsing with water right after eating sour treats helps. When reading ingredient lists, those with food sensitivities or allergies pay attention to the source of citric acid and stay tuned to how their bodies react.

Citric acid isn’t an enemy, but it does remind us that labels matter and everyone’s body has its own response. Learning to listen and ask questions keeps everyday choices on your side.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid |

| Other names |

2-Hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid C6H8O7 Lemon salt Sour salt 3-Carboxy-3-hydroxypentanedioic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɪtrɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | 2-hydroxypropane-1,2,3-tricarboxylic acid |

| Other names |

2-Hydroxy-1,2,3-propanetricarboxylic acid C6H8O7 Citronensäure Lemon acid E330 3-Carboxy-3-hydroxypentanedioic acid |

| Pronunciation | /ˈsɪtrɪk ˈæsɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 77-92-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1721818 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30769 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1405 |

| ChemSpider | 617 |

| DrugBank | DB04272 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03b7d8f6-6b3a-44a1-bdf5-72e5e6c9fd44 |

| EC Number | 200-066-2 |

| Gmelin Reference | 60885 |

| KEGG | C00158 |

| MeSH | D002244 |

| PubChem CID | 311 |

| RTECS number | GE7350000 |

| UNII | KRK17JT0RP |

| UN number | UN0775 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID4020011 |

| CAS Number | 77-92-9 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1723203 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30769 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1131 |

| ChemSpider | 576 |

| DrugBank | DB04272 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03d6a340-6ecc-443d-9a9c-e3a84cff4d7b |

| EC Number | 211-529-5 |

| Gmelin Reference | 3436 |

| KEGG | C00158 |

| MeSH | D019355 |

| PubChem CID | 311 |

| RTECS number | GE7350000 |

| UNII | 2968PHW8QP |

| UN number | UN0775 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5029105 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C6H8O7 |

| Molar mass | 192.12 g/mol |

| Appearance | White or colorless crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.665 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Soluble (192 g/L at 25 °C) |

| log P | -1.72 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: <0.1 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.13, 4.76, 6.40 |

| Basicity (pKb) | pKb ≈ 11.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.493 |

| Viscosity | 1.7 mPa·s (20 °C) |

| Dipole moment | 4.11 D |

| Chemical formula | C6H8O7 |

| Molar mass | 192.12 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.66 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Very soluble |

| log P | -1.72 |

| Vapor pressure | Vapor pressure: <0.01 hPa (20 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 3.13 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 3.13 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.493 |

| Viscosity | 1.7 cP (20°C) |

| Dipole moment | 3.71 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 189.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1541 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1986 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 189.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -945 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | –1986 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A09AB13 |

| ATC code | A09AB07 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | **"Warning; Eye Irrit. 2; H319: Causes serious eye irritation. [P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313]"** |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation |

| Precautionary statements | P264, P270, P280, P301+P312, P305+P351+P338, P330, P501 |

| Autoignition temperature | 1010°F (543°C) |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 3,000 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | CAS# 77-92-9 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not established |

| REL (Recommended) | 50 mg/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Main hazards | Causes serious eye irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, GHS eye irrit. 2 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | Keep container tightly closed. Store in a cool, dry place. Wash hands thoroughly after handling. Avoid breathing dust. Wear protective gloves/eye protection. If in eyes: Rinse cautiously with water for several minutes. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 2-0-0 |

| Flash point | >100°C |

| Autoignition temperature | 1010 °C |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | 3000 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WA1230000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL: Not Established |

| REL (Recommended) | 2500 mg/kg bw |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | No IDLH established. |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Isocitric acid Cis-Aconitic acid Tricarballylic acid Succinic acid Malic acid Fumaric acid Oxaloacetic acid |

| Related compounds |

Isocitric acid Citric anhydride Sodium citrate Calcium citrate Magnesium citrate |