Calcium Propionate: Exploring Its Journey, Science, and Future

Historical Development

Bakers and food producers in the early twentieth century started searching for ways to keep bread and baked goods fresher for longer. Before refrigeration became widespread and consistent, stale bread or moldy cakes meant money down the drain. People noticed that some bread lasted longer on the shelf if they used certain milk derivatives. Researchers traced this effect to calcium propionate, a compound that acts as a mold inhibitor. Chemistry had an answer for age-old problems, and by the 1930s, calcium propionate entered the food business as an official preservative. By the mid-century, food scientists realized that this salt could help not only bread but other foods and animal feeds stay fresh and safe in different environments. The story of calcium propionate is a clear example of how necessity and science work together, turning everyday spoilage into an affordable, scalable innovation.

Product Overview

Calcium propionate shows up in food ingredient lists more often than most people realize. Folks buying commercial bread, tortillas, pastries, or even dairy products probably consume it in small quantities regularly. In foods, the main goal is to extend the shelf life by stopping the growth of mold. Manufacturers value calcium propionate’s properties because it dissolves easily, works in a wide pH range, and doesn’t distort the color, taste, or texture in normal formulations. Besides the food sector, calcium propionate finds a role in animal nutrition and some pharmaceutical products. It works quietly in the background, with most consumers taking its benefits for granted.

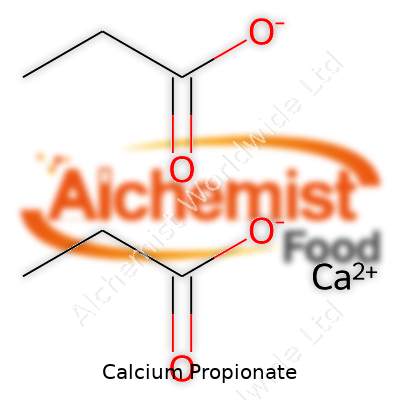

Physical & Chemical Properties

Chemists describe calcium propionate by the formula Ca(C2H5COO)2. It usually comes as a white crystalline solid or powder, odorless or with a faint, sometimes soapy smell. It remains stable under regular storage and easily dissolves in water, which matters when mixing dry and wet ingredients in food production. Because it’s a salt, it doesn’t degrade quickly when exposed to light and air, helping ensure the preservative performs throughout the expected shelf life of the food. In laboratory tests, it holds up between pH 5 to 9, covering most conditions found in typical baked goods and processed foods.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Food safety authorities set strict parameters for food-grade calcium propionate. Manufacturers test for purity, moisture content, and heavy metals, ensuring contaminants don’t slip through the cracks. European and US standards agree on limits for lead, arsenic, and other impurities. On product labels, calcium propionate appears as E282 in the EU and simply as “calcium propionate” in the US and many other countries. Because of the worldwide trade, suppliers must meet each region's requirements to export and grow their markets. Most labels reflect this detail, listing it under “preservatives” on ingredient panels. For industrial buyers, vendors supply certificates of analysis along with bulk shipments, giving downstream manufacturers peace of mind that they fulfill regulatory obligations.

Preparation Method

Commercial production of calcium propionate happens primarily through the neutralization of propionic acid with calcium carbonate or calcium hydroxide. Propionic acid, commonly produced by the fermentation of sugars using specific bacteria or by petrochemical synthesis, reacts with calcium sources to yield calcium propionate and water. Factories filter, dry, and crush the product into uniform powder or crystals. The process isn’t glamorous or complex compared to some modern specialty chemicals, but it’s precise. Attention focuses on controlling reaction temperatures and removing excess moisture to avoid caking or clumping in finished products.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Chemically, calcium propionate stands firm under normal conditions. It takes strong acids to release propionic acid from its salt form during digestion or baking. Bakers sometimes tweak recipes with acidic or alkaline ingredients, but calcium propionate resists breaking down until needed. For developers seeking tailored preservation, chemists sometimes combine it with other preservatives to offer broader antimicrobial effects or create specialty blends to address unusual spoilage organisms. Changes in formulation demand careful trialing because the wrong tweak can impact the effectiveness or cause off-flavors, which consumers notice.

Synonyms & Product Names

Calcium propionate goes by several names in commerce and science. In chemical catalogs and regulatory lists, it appears as calcium dipropionate or calcium di-n-propionate. European food law refers to it as E282. In some food lists, “propanoic acid calcium salt” shows up, but most labels just stick with the standard name. It's best recognized where bread, tortillas, pastries, processed cheeses, and some animal feeds are sold.

Safety & Operational Standards

Regulatory agencies including the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), and the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) review and approve calcium propionate. They set daily intake limits based on animal and human studies, keeping well under the threshold for adverse effects. Food plants handling calcium propionate issue clear instructions on storage and personal protective equipment, since high concentrations in powder form can irritate the skin, eyes, or respiratory tract. Proper training, dust control measures, and storage away from acids or oxidizers help operations run smoothly and keep the workforce safe.

Application Area

Bakers stand at the front line of calcium propionate use, from industrial bread factories to medium-sized bakeries. Processed cheese manufacturers rely on it too, especially for blocks and slices that ship long distances or sit in refrigerators for weeks. Beyond food, animal feed producers add calcium propionate to ruminant diets to inhibit mold in stored grains and silage. In pharmaceuticals, calcium propionate occasionally finds use as a preservative in some liquid and gel formulations. This spread across diverse sectors keeps demand steady, as concerns over food waste and safety never really fade.

Research & Development

Food chemists and microbiologists continue searching for better ways to target spoilage microbes as tastes evolve and supply chains stretch across continents. Calcium propionate researchers track resistance in molds and investigate combinations with natural antimicrobials such as essential oils and enzymes. Ongoing work follows consumer demands for “clean label” products, where some makers look to lower preservative use yet keep the same safety margins. Engineers push for new production techniques that produce cleaner, more consistent granules or powders, optimizing mixing and dosage in automated plants. There’s also rising interest in sustainable production—fermenting propionic acid from agricultural waste instead of petroleum.

Toxicity Research

Scientists studying safety examine how calcium propionate breaks down in the human gut, focusing on potential metabolic effects, allergenicity, or links to chronic health issues. Decades of research in humans and animals validate its low toxicity at levels approved for food. Still, new studies occasionally spark public conversation, especially with shifting attitudes about food additives. High doses might cause mild digestive trouble in some sensitive individuals, but uncontaminated commercial offerings, used per regulations, keep risk minuscule. Long-term monitoring and regular review by expert panels guard public confidence as food systems change.

Future Prospects

Looking at the years ahead, the market for calcium propionate likely grows as concerns about food loss and consumer safety intensify worldwide. Modern supply chains stretch over great distances, making reliable preservation more important than ever. At the same time, the “clean label” trend encourages a look at dosage reductions, ingredient lists with fewer E-numbers, and even new fermentation-based production that slips more naturally into sustainable business models. Food scientists push for more research into combined preservative systems, lower environmental impacts, and better understanding of the microbiome’s response to routine preservative intake. The necessity to reduce food waste and the drive for food safety keep calcium propionate in the spotlight even as consumer perspectives shift and regulatory landscapes evolve.

What is Calcium Propionate used for?

Stopping Mold Before It Starts

Fluffy white bread from the store stays fresh in your cupboard far longer than any loaf baked at home without preservatives. Most folks don’t think twice about what makes that possible. Tucked inside the ingredients list, you’ll spot “calcium propionate”. This isn’t some mysterious chemical dreamed up in a lab for no reason. Bakeries and large food makers count on it because bread molds fast, especially where kitchens get humid. Mold not only ruins food, it makes people sick. Every kid who’s opened a lunchbox to find a blue-green sandwich understands why families want fresher bread, not fuzz.

Calcium propionate stops mold and certain bacteria in their tracks. It breaks up the metabolism of cells harmful to food, without hurting the yeast needed for fluffy loaves. A loaf can stay on the shelf days longer, saving grocery stores money and letting families buy a week’s worth of bread without making daily trips to the shop. Large-scale bakeries depend on these kinds of preservatives, otherwise a truck full of sandwich rolls won’t make it to market before turning stale or green.

Backed by Science, Watched Closely

Scientists and food safety panels around the world keep a close eye on how much calcium propionate ends up in food. The FDA, European Food Safety Authority, and Health Canada have all pointed out its safety in the amounts used for food. A careful review matters. Few things get more personal than what goes into our stomachs. People eat it every day in slices of bread, tortillas, baked goods, and even some cheeses. Research in dozens of studies finds the body breaks it down quickly, turning it into water and carbon dioxide.

There’s a reason so many food scientists support its use: bread waste used to be a real cost for companies and families. Up to a third of all food produced gets tossed out because it spoils before anyone can eat it. Cities spend millions every year dealing with that waste. Keeping food fresher a little longer cuts down costs for everyone — and helps make nutritious food available to people in places with less frequent grocery delivery.

Are There Downsides?

Some consumers say they want fewer additives on their plate, worried about the impact of modern preservatives. Every so often, people link food chemicals to allergies or changes in child behavior. These stories matter, because people want trust in the food they eat. So far, solid evidence from large groups hasn’t shown direct harm at levels found in store bread. Most countries set strict limits so food doesn’t include more than needed, and the amounts are hundreds of times lower than what could create side effects.

Bakeries looking for a “clean label” sometimes pick alternatives like vinegar or sourdough. Those methods aren’t as strong at holding off mold in humid places. Sharing information openly about how and why calcium propionate shows up in food helps people make real decisions at the store. Food labels and honest conversations with food scientists can bridge the gap between kitchen habits and factory production.

Trust and Choice at the Store

Nobody likes to waste food or spend too much at the checkout counter. Longer-lasting bread gives busy families flexibility, reduces trash, and helps stores avoid empty shelves. If someone wants to avoid calcium propionate, it’s possible to bake at home or pick from “no preservatives” bakery sections. Most people appreciate having safer choices, whether it’s a homemade loaf or something that keeps through the week in a breadbox. In food, like much else, facts and trust live side by side.

Is Calcium Propionate safe to eat?

What is Calcium Propionate?

Walk down the bread aisle in a grocery store, and you'll spot calcium propionate on more labels than you might expect. Bakers turn to this additive to keep mold from spoiling loaves too early. Technically, it’s a type of salt. My kids’ sandwich loaves would never last more than a few days on the counter without it, and most home bakers will agree: bread left without preservatives grows fuzzy with mold pretty quick.

Safety Backed by Research

Plenty of parents pause before feeding their families anything that sounds more like a chemistry experiment than food. I used to dig through food safety sites every time an unfamiliar ingredient showed up at home. Agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) list calcium propionate as “generally recognized as safe.” The European Food Safety Authority and World Health Organization have both reviewed it and placed similar confidence in its typical use in foods.

Researchers test additives on both animals and people as part of the approval process. Pretty high doses need to be fed to rats before they show any kind of negative reaction. In most bread and bakery products, amounts remain quite a bit below those test levels. This gives confidence that the small quantities in a sandwich or slice of pizza don’t pose a major threat, no matter what type of loaf you prefer.

Addressing Health Concerns

The word “additive” sends up red flags because people feel uneasy about chemical names. News articles have linked calcium propionate to possible behavioral changes in children, citing small studies where some kids showed hyperactivity. Full-scale reviews looked at the evidence and called it weak and inconsistent. Just about everything in a regular diet has some story attached if you look hard enough, but actual population outcomes never matched the headlines.

Doctors sometimes see patients react to preservatives, but these cases turn out to be very rare. If bread, buns, or pastries make someone feel off, an elimination diet with a dietitian’s guidance can help narrow down the culprit. Most families never see any effect. As someone who’s worked with nutritionists and read hundreds of food labels for health-conscious relatives, honest answers matter: calcium propionate simply doesn’t stand out as a problem for most healthy people.

Bigger Questions About Our Food Choices

People ask about food additives because they care about real food and health. Whole foods—like apples, eggs, and nuts—feel safer because people understand them. Tossing all preservatives aside would leave most bread either rock hard or moldy within days, creating more food waste. People lived for centuries before food preservatives, but spoiled food sent plenty of people to the doctor. Food safety scientists see benefits in keeping mold at bay, especially for the elderly or those with mold allergies.

Balancing Risks and Solutions

Anyone worried about preservatives has two solid choices: bake bread at home or look for brands that skip additives and sell smaller loaves meant for quick eating. It’s always possible to freeze half a fresh loaf and avoid food waste. For the people who want convenience and affordability, preservatives like calcium propionate keep food safer and waste lower. Instead of banning preservatives, labeling laws with clearer warnings would allow everyone to decide for themselves.

Food safety isn’t just about chemicals or scary headlines, but about what families need and actually eat. For most, calcium propionate is just another helper keeping food safe until it’s time to eat.

Does Calcium Propionate cause any side effects?

What Is Calcium Propionate Doing in Food?

Open most bags of sandwich bread or tortillas and you’ll spot calcium propionate on the label. Bakers and food makers rely on it to stop mold and bacteria from spreading. Fresh bread goes stale or moldy in days. With calcium propionate in the mix, those loaves last for weeks on a shelf. It sounds helpful. But people, especially parents, have questions. Is this stuff safe to eat all the time? Could it cause headaches or stomach trouble? That’s worth looking at.

Science Says It’s Safe—At Common Levels

Regulatory agencies, including the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority, have checked out calcium propionate. They’ve looked at piles of studies. These organizations say people can eat foods with typical levels of it without worry. I checked numbers. Most store bread has less than 0.3% calcium propionate by weight. That’s much lower than the amounts used in some studies that looked for problems.

Calcium propionate ends up in your body as propionic acid, a short-chain fatty acid you’d find in Swiss cheese and in your large intestine after whole grains or fiber break down. Your gut is already built to handle it. Your liver changes propionic acid to energy your body can use. Most people never notice any effects at all from eating it in baked goods.

Reports of Side Effects—What’s Going On?

Turn to forums or social media and worries pop up: “Bread makes my kid hyperactive,” or “I get headaches from sandwich loaves.” Some folks feel calcium propionate could play a role. Research from the 1980s looked at kids who showed hyperactivity or trouble sleeping after eating bread and baked goods with propionate preservatives. The connection wasn’t strong. Recent studies also struggle to pin blame on calcium propionate for behavioral issues or allergic reactions. Most clinical trials are small or show mixed results.

From my own experience working in the food industry, I’ve talked with parents who cut out certain bread brands and found behavior improved for their children. Was it calcium propionate specifically or a whole mix of food additives? No one could say for sure. What’s clear: some people believe symptoms like headaches, stomach cramps, or behavior shifts fade when they avoid this additive. Scientific evidence hasn’t nailed down a cause, but real-life stories matter to families looking for answers.

Who Should Watch Out?

Some people may be more sensitive than others. Individuals with conditions affecting their gut microbiome might complain of bloating or discomfort, especially after heavy processed food diets. Those with rare metabolic disorders, such as propionic acidemia, already avoid foods with this ingredient under a doctor’s care.

What’s the Fix?

If you don’t feel great after eating store-bought bread, switching to bakery loaves or homemade bread removes most chemical preservatives, including calcium propionate. Bread from small bakeries usually goes stale faster, but you control what’s inside. Some grocers now stock “clean label” and preservative-free versions to meet growing demand. Choosing these options or varying your diet makes sense if you’re concerned, even without rock-solid proof of harm for most people.

The key is to listen to your body. Most people won’t notice a thing. For a handful who do, reading labels and trying alternatives becomes a common-sense way to address symptoms. Plenty of fresh, simple foods don’t last long on a shelf—sometimes, that signals fewer extras inside.

Is Calcium Propionate a preservative?

What Calcium Propionate Does in Bread and Food

Spend five minutes reading ingredient lists in any grocery store’s bread aisle, and you’ll likely spot calcium propionate every few labels. People don’t always know what this name means, but bakers and food scientists rely on it every day. Calcium propionate helps keep mold away from bread and baked goods, stretching out the days before anything grows fuzzy or smells off in your kitchen.

Bacteria and molds thrive in moist, carbohydrate-rich environments. Bread is the textbook example. Before food companies used preservatives, bread often turned moldy in less than two days. That meant bakers had to toss unsold loaves, hurting wallets and wasting food. The modern food chain leans on ingredients like calcium propionate for both quality and safety.

Why Bakers and Food Producers Use Calcium Propionate

Shelf life isn’t just a buzzword for large stores and bakeries. It affects how far food travels and how much money a business can save. Calcium propionate blocks mold growth, not by killing fungi outright but by interfering with their ability to build cell walls and digest nutrients in bread. For everyday folks shopping at supermarkets, this translates to loaves keeping longer, reducing food waste at home as well.

From my own baking, skipping any sort of preservative cuts shelf life dramatically—even storing homemade bread in tight containers only buys a day or two. In the food industry, longer shelf life means less product loss and safer food, especially in warm climates where mold multiplies fast.

Health, Safety, and Regulations

The FDA and World Health Organization both allow calcium propionate as a food additive. Scientists have studied its safety over decades. For most people, the body breaks it down into calcium and propionic acid, both harmless. Some parents worry about reactions in kids with sensitivities, but large studies have not shown consistent links to allergies or behavioral problems.

Still, large bakery chains and ingredient makers monitor additive levels closely. Most producers use well below the maximum allowed, typically around 0.2–0.5% in bread recipes. These controls grow more important as consumers pay closer attention to food labels and demand accountability about what goes into their meals.

Alternatives and Consumer Choice

Some bakers use vinegar, cultured wheat, or natural sourdough starters to slow down mold instead of chemical preservatives. These options work, but don’t usually deliver the same consistency or shelf life in large-scale production. Small bakeries sometimes skip preservatives since their bread sells quickly, or because local shoppers want “clean label” recipes.

Supermarkets and industrial bakeries juggle cost, consumer trust, and food safety. People who want to avoid calcium propionate can look for artisan loaves with shorter ingredient lists, but will trade some convenience in the process. Across the world, food companies and health authorities keep re-examining these additives, pushed by both health research and changing public attitudes.

What’s Next for Preservatives?

Innovation in food science keeps moving. Researchers explore plant-based mold fighters and new packaging techniques. At the same time, clear labeling matters. People deserve easy access to facts—what each preservative does and how it fits into the food chain. Calcium propionate remains a standard ingredient for many bakers. Awareness and informed choice empower shoppers, whether grabbing a quick sandwich loaf or baking bread at home.

Can Calcium Propionate be used in baking?

The Role of Calcium Propionate in Everyday Baking

Home bakers and professionals have both run into the same trouble at some point: fresh bread or pastries turn moldy in just a few days, especially during the hotter months. That’s where calcium propionate steps in. It’s not some mystery chemical—this compound serves a specific purpose. In the world of baking, it’s added to keep bread, rolls, and other baked items fresher for longer, holding off mold and bacteria that thrive in moist, warm kitchens.

Why Bakeries Trust Calcium Propionate

Bakers work on tight schedules. Imagine running a local bakery and losing half your daily batch to mold before customers even walk in. Losing money each week adds up fast. The solution for many has been to blend calcium propionate into dough. According to published food safety research, this compound interrupts the growth cycle of common spoilage organisms like mold, extending shelf life without noticeably changing taste or texture. Over the years, plenty of companies have relied on it for both preservation and cost control.

Food Safety and Personal Experience

People want to know what goes into their food. It helps to look at research from organizations like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which recognizes calcium propionate as “generally recognized as safe” at typical usage levels. My own experience working at a family bakery backs this up—we always looked for substances approved by food safety agencies. Customers liked our breads with fewer preservatives, but once summer came, skipping calcium propionate sometimes meant dumping trays of beautiful but fuzzy loaves. There’s always a balance between fresh, simple recipes and keeping food safe to eat long enough to enjoy it.

Health and Labeling Concerns

Some folks stress about chemicals in their bread, especially if they deal with allergies or digestive issues. Most people can eat foods with calcium propionate without trouble. Reports from organizations like the European Food Safety Authority support its safety. There’s been concern about certain individuals, notably children, experiencing headaches or behavioral changes, although evidence remains limited. As a baker and a parent, I always recommend checking ingredient lists and listening to your body. For anyone with special concerns, making bread at home without additives solves that problem, at least for smaller batches.

Alternatives for the Cautious Baker

Artisans looking for label-friendly approaches can reduce moisture, bake in smaller batches, or try natural inhibitors. Vinegar and sourdough cultures help, although they change taste profiles and may not halt mold as reliably in humid climates. For those selling packaged bread or supplying stores, nothing beats the efficiency of calcium propionate. Small-scale bakers have more flexibility—so experimenting with recipes, refrigeration, or sourdough can work out if long shelf life isn’t a top concern.

Finding the Right Approach for Your Kitchen

Baking involves more than recipes. Hygiene, climate, and storage all play a part. Calcium propionate works as a tool to support quality and safety, especially for those needing bread to stay fresh on the shelf or in lunchboxes. If your kitchen stays busy and you’re constantly replenishing, there’s less pressure to use it. For everyone else, especially anyone shipping or storing baked goods, it adds reliability. Understanding why it’s used and when it’s needed lets both bakers and eaters make better choices about what they're baking and eating each day.

What is calcium propionate used for?

Walking Through the Grocery Store: Where Calcium Propionate Pops Up

Grab a loaf of bread off the shelf. Flip the package over and read the ingredients list. Calcium propionate often turns up about halfway down. Most folks miss it. Kids running around, tight schedules — who’s got time to decode a list of twenty odd-sounding ingredients? But that tiny listing does a lot more for bread than most realize. Bakers add it to keep bread soft and fresh for longer. If you’ve ever wondered why grocery store bread seems to outlast homemade, here’s your answer.

What It Does Behind the Scenes

Food molds like Penicillium and Aspergillus love warm, moist food. They can turn a fresh loaf into a fuzzy science project pretty quickly, especially during hot summers. Calcium propionate stops those molds from spreading, making it possible for families to keep bread for days instead of hours. This is where things get practical. Around 1950, the commercial baking world wanted to cut down on food waste. Calcium propionate gave them a way to promise longer shelf lives, reducing spoilage in transit and on shop shelves.

Why Beyond Bread?

The uses don't stop at bread. Tortillas, pastries, and even processed cheeses all draw benefits from this preservative. Large cafeterias, busy restaurants, and even school lunch programs rely on it since tossing out spoiled food costs real money. You’ll also spot it in packaged pasta and sometimes even dried fruit. Some dairy products — especially those prone to surface mold — tap calcium propionate to cut wastage too.

Is It Safe? What Science Says

Families worry about additives, and for good reason. No one wants extra chemicals floating around in their kids’ lunches. Scientists have studied calcium propionate for decades. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration classifies it as generally recognized as safe, provided it’s used in approved amounts. International food safety experts, including the World Health Organization, reached the same conclusion. The body breaks it down a lot like eating a few extra bites of cheese — it turns into regular metabolites, absorbed and used as energy.

Concerns and Looking for Alternatives

Some stories exist about preservatives causing headaches or hyperactivity, but evidence for calcium propionate causing major issues is thin. Parents whose kids have special sensitivities might try preservative-free bread, but most reactions come from much larger doses than found in food. For those wishing to avoid it altogether, local bakeries sometimes make bread fresh daily and skip all preservatives. The catch? That bread doesn’t last past a day or two, so buying smaller amounts or freezing what isn’t used ends up necessary.

Big Picture: Food Waste and Preservation

Tossing moldy bread means wasted money and resources. Additives like calcium propionate play a real role in keeping food costs down and reducing waste. No one ingredient comes without debate, but in this case, the science holds up. At the end of the week, most folks just want bread that keeps long enough to make it to the next grocery run.

Is calcium propionate safe to consume?

Everyday Encounters With Calcium Propionate

Taking a stroll down the bread aisle, you might notice how loaves stay soft and fresh for days. This is where calcium propionate comes in. Bakers use it to hold back mold growth, protecting bread from spoiling too fast. The same goes for tortillas, baked treats, and even processed cheese. The food industry has leaned on this preservative for decades, and it gets tossed into recipes more often than most people realize.

Breaking Down the Science

Researchers have combed through the effects of calcium propionate on the body. The compound is a salt formed from calcium and propionic acid, which naturally forms in the gut when bacteria break down dietary fiber. This isn’t some mysterious chemical brewed in a lab for the first time last week. Health authorities, including the FDA, consider calcium propionate safe in the amounts commonly eaten in foods. The European Food Safety Authority landed on that same verdict, reviewing studies on animals and humans.

Researchers paid close attention to how much people typically get through bread and other baked goods. No evidence turned up showing harmful effects in healthy adults or kids at levels found in normal diets. The World Health Organization reviewed the data and set an acceptable daily intake.

What About Rumored Side Effects?

Online forums love to point fingers at preservatives, claiming links to hyperactivity, allergies, even headaches. A few small studies drew connections between calcium propionate in bread and restlessness in children. Larger follow-up studies either failed to confirm this or found the effect only appeared when kids ate very high amounts. Of course, if someone notices their child shaky or agitated after a certain food, it makes sense to talk with a doctor and try cutting it out. But for most people, science hasn’t found a strong link between bread preservatives and behavior issues.

Why Bother With Preservatives?

Nobody likes pulling out a loaf of bread only to find fuzzy mold patches. Food waste becomes less of a headache with preservatives like calcium propionate. Less spoilage helps families save money and keeps goods safe until the last slice. This becomes even more important in warm or humid places, or for folks who can’t buy groceries every day. The preservative slows down bacteria and mold, giving bread a longer life without adding more sugar or processing.

Choosing What Works Best For You

Having worked in a bakery myself, I’ve seen how much trouble mold brings in a kitchen without any preservative. Fresh, homemade bread often sours in a couple of days. Still, not everyone wants preservatives. People who prefer to keep food as simple as possible might skip standard supermarket loaves and bake at home or buy from local bakers using old-fashioned recipes. That’s fine, too. Everyone should feel comfortable reaching for the options that suit their values and health needs.

Keeping Tabs On Additives

Food regulation isn’t perfect, and it’s a good idea to stay aware of what’s in your food. Reading ingredient labels lets folks know what they’re putting in their bodies. Regulatory agencies keep testing additives as science evolves, changing rules if new risks show up. For those who want to avoid calcium propionate, plenty of breads advertise “preservative-free” or list just a handful of ingredients. The food supply offers more choices than ever, letting eaters find what lines up with their needs.

Does calcium propionate have any side effects?

What Is Calcium Propionate?

Walk down a bakery aisle and chances are, you’ll find bread with a long shelf life. One reason is calcium propionate. This preservative fights off mold and some bacteria, which keeps food fresher for longer. Food companies like it because it helps cut down on waste. It appears in bread, tortillas, pastries, and sometimes dairy or processed meat. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, European Food Safety Authority, and experts around the world have studied it and marked it as “generally recognized as safe.”

So, Are There Side Effects?

Any ingredient that sticks around in the food supply draws attention. Some people report headaches or stomach upset after eating food with calcium propionate. Most folks eat these foods for years and never notice a single symptom. A study published in the late 1990s by the Journal of Paediatrics shed light on a possible link between calcium propionate and increased irritability, restlessness, or inattention in children. Only a small test group and a high dose produced that result, and repeated studies have not strongly backed it up. Still, it started conversations in schools and households about what goes into kids’ lunches.

Gut Reactions and Digestion

Occasionally, people with sensitive stomachs say they feel bloated, get gas, or experience discomfort. Medical professionals see only rare cases where calcium propionate clearly causes symptoms. People with chronic digestive disorders may want to check labels and limit processed food if it leads to regular problems.

Food Allergies: Fact or Fear?

Social media and blogs sometimes describe calcium propionate as an “allergen.” According to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, true allergies rarely happen. This additive does not trigger the immune system as peanuts or shellfish do. The negative buzz about preservatives sometimes pushes people to avoid bakery goods more out of caution than from direct evidence.

What Do Experts Say About Long-term Use?

Doctors and nutritionists agree that moderation helps. A well-rounded diet leans on fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and whole grains. Breads and pastries with calcium propionate live in the “sometimes” category for most health experts. In animal studies, even high doses don’t cause tumors or major organ issues, and experts judge the amounts used in food as safe.

Looking at Solutions

Consumers can read ingredient lists and pick brands using less processed ingredients. Fresh bread goes stale quicker, but some small bakeries avoid preservatives, and local choices often skip calcium propionate altogether. Home baking relies mostly on basic flour, yeast, and salt, which sidesteps the question entirely. Larger companies respond to public demand; some already offer preservative-free options.

People who feel concerned about this additive can keep a food diary, note any symptoms after eating processed goods, and talk it over with a qualified healthcare provider. Growing awareness pushes food makers to look for simple labels and shorter ingredient lists. Staying informed about what goes into your food — and listening to your body — never goes out of style.

Is calcium propionate suitable for people with allergies?

Understanding Calcium Propionate

Calcium propionate shows up in lots of bread, tortillas, pastries, and processed cheese. It keeps mold away and helps products last longer on shelves. Bakeries rely on it to help bread stay fresh instead of getting spotty after a few days. Looking at the label, it might sound strange, but for most people, it plays a quiet, helpful role. Still, folks with allergies have every right to pay close attention to what’s inside their food.

Common Allergy Concerns

Allergies make life complicated. It can be hard enough avoiding peanuts or shellfish, let alone tracking down all the additives in processed foods. Calcium propionate does not come from common allergenic sources like nuts, dairy, eggs, or soy. It’s made by treating propionic acid with calcium hydroxide, and neither raw material triggers the 'Big Eight' food allergies on their own.

Despite this, some people report reactions after eating foods with calcium propionate. They might feel headaches or stomach discomfort, and parents sometimes wonder if it’s behind their child’s hyperactivity. Research from the 1980s hinted at symptoms resembling behavior changes in a small group of children, but later studies haven’t found any solid connection. Scientists who focus on food safety say evidence linking calcium propionate to classic allergy symptoms looks thin.

Is It Safe for Most Allergic Adults and Kids?

Calcium propionate ranks as "Generally Recognized as Safe" by the FDA. Testing in animals and humans hasn’t revealed allergic risks the way, say, peanuts or shellfish have. Most allergic reactions blamed on packaged foods turn out to come from cross-contamination or hidden milk, egg, or nut ingredients—not preservative additives like calcium propionate.

But real people sometimes defy studies and categories. Some individuals with a condition like chronic urticaria (hives) find that certain preservatives spark their skin symptoms. For them, doctors recommend elimination diets or detailed food diaries to spot triggers. Every immune system has quirks, so there’s always a chance for exceptions, even if published research points to low risk for allergic reactions.

Watching Out for Additive Sensitivities

It helps to know the difference between a food allergy and a food intolerance or sensitivity. Allergies cause the immune system to overreact, sometimes in dramatic ways—rashes, trouble breathing, even anaphylaxis. Sensitivities or intolerances might mean headaches, gut problems, or brain fog, but they don’t involve the immune system in the same way. Calcium propionate can land in the sensitivity zone for a few individuals. Medical teams call these "non-allergic hypersensitivity reactions," and they don’t show up on allergy tests.

Keeping close track of symptoms with a registered dietitian or allergist backs up a gut feeling with real evidence. Blood or skin tests won’t catch a non-allergic reaction to calcium propionate, but a controlled elimination challenge can help sort out the truth.

Steps for Safe Eating

Anyone with a history of reactions to food additives or unexplained chronic symptoms should reach for simple ingredient lists, home-cooked meals, and whole foods more often. Packaged bread or baked goods usually list calcium propionate among the ingredients, so checking labels matters. For families tackling multiple allergies, sharing clear records with healthcare providers leads to smarter food choices. Online allergy support groups provide tips, recipes, and real-world advice that doctors sometimes miss.

Food safety teams around the world keep setting safe levels for additives, adjusting as new evidence comes forward. People who know they’re sensitive can avoid surprises by connecting with an allergist before making changes to their diet. It’s not always about restriction—it’s about clarity and peace of mind at the dinner table.

How does calcium propionate prevent mold in food?

The Spoiler in the Story: Mold

Bread left out for a few days gets fuzzy. That familiar blue-green mold comes quick, especially if the kitchen gets humid. I’ve tossed plenty of half-eaten loaves over the years. Food waste still drives me nuts, and mold seems unstoppable at home without help. Bakeries and large food makers have it worse. Once that product leaves the oven, a countdown to spoilage starts ticking. That’s where calcium propionate steps up.

The Mold Problem Isn’t Just Personal

Every year, millions of tons of food wind up in the trash because they spoil before anyone eats them. Mold doesn’t only taste bad—it poses real health risks, especially if spores or mycotoxins show up. For bakery businesses, mold costs money and damages trust with customers if bread or cake goes off early. Modern food reaches farther than the neighborhood bakery. Bread makes long journeys and sits on shelves longer. That’s why companies started looking for safe ways to fight mold without chemicals that scare people.

How Calcium Propionate Works

Calcium propionate offers a simple solution. It prevents the spread of mold and certain bacteria by interrupting their life cycle. The science isn’t hard to grasp. Mold grows best in moist, slightly acidic foods like bread. Calcium propionate breaks up the process inside mold cells, so they struggle to reproduce or break down carbohydrates for energy. Instead of growing and spreading, mold just stalls out.

From the consumer side, it means buying a loaf on Sunday still gives you decent sandwiches through Thursday. Bakers can sell with fewer worries about product recalls or health scares.

Safety: What We Know So Far

People remain understandably cautious about additives in food. Calcium propionate gets plenty of scrutiny. So far, science supports its use in bread and other baked goods. Studies from food safety agencies—like the FDA and the European Food Safety Authority—find that it doesn’t build up in the body and comes out through natural processes. Nobody wants mystery chemicals in their kid’s lunch, and this one checks out over decades of use.

Health and Taste Concerns

Some people report mild digestive discomfort, but reactions stay rare and mild compared to the risks of eating moldy bread. Many countries set strict limits on how much gets added, so you never see sky-high amounts. Bread tastes the same. Some bakers argue it can change the crust’s crispness a bit, but side-by-side tests rarely reveal differences to most eaters.

Room for Better Solutions

Many people want even fewer additives in their food. Bakers and food scientists experiment with natural solutions—changing recipes, sourdough cultures, or smart packaging. Nothing matches the convenience and proven history of calcium propionate yet. Exploring new ways to block mold makes sense, but the reality of shipping bread around the country keeps this preservative relevant for now.

What this Means in Everyday Life

Walking down any supermarket bread aisle, the loaves feel soft and stay edible for days. People keep tossing less food, saving money, and trusting that their snacks won’t make them sick. Calcium propionate doesn’t turn food into something unnatural. It keeps bread out of the trash and adds a layer of safety where we need it. Food safety experts keep testing, but for now, this additive makes our daily lives easier and our food supply safer.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Calcium propanoate |

| Other names |

Calcium dipropionate E282 Propionic acid calcium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkælsiəm proʊˈpiː.ə.neɪt/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | Calcium propionate |

| Other names |

Calcium dipropionate E282 Propionic acid calcium salt |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkæl.si.əm proʊˈpiː.ə.neɪt/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 4075-81-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 3976802 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:31343 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201613 |

| ChemSpider | 5606 |

| DrugBank | DB11157 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 03e9b8de-257d-4e1b-8be7-5332c2c8a9c2 |

| EC Number | EC 223-795-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 63551 |

| KEGG | C00783 |

| MeSH | D002121 |

| PubChem CID | Perhaps the answer is: 8217 |

| RTECS number | RR8750000 |

| UNII | H9P53J927K |

| UN number | UN3208 |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | DTXSID5020672 |

| CAS Number | 4075-81-4 |

| Beilstein Reference | 8000028 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:31343 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201112 |

| ChemSpider | 8156 |

| DrugBank | DB11157 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 03-2119946957-21-0000 |

| EC Number | EC 223-795-8 |

| Gmelin Reference | 67658 |

| KEGG | C00783 |

| MeSH | D002121 |

| PubChem CID | 5269 |

| RTECS number | RTECS number for Calcium Propionate: **UE9100000** |

| UNII | J6K4F9N0O5 |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Ca(C2H5COO)2 |

| Molar mass | 186.22 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.19 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Easily soluble in water |

| log P | -2.51 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | 10.0 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 8.35 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.495 |

| Dipole moment | 1.98 D |

| Chemical formula | Ca(C2H5COO)2 |

| Molar mass | 186.22 g/mol |

| Appearance | White crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 1.21 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Moderately soluble |

| log P | -2.51 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | pKa 4.88 (of propionic acid) |

| Basicity (pKb) | 6.12 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | Diamagnetic |

| Dipole moment | 2.78 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 221.5 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1553.3 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2010.7 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 155.7 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹ |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1387.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -2021.1 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | A11AA04 |

| ATC code | A07BC04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. |

| Flash point | > 250°C |

| Autoignition temperature | Not autoignitable |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 4,980 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose) of Calcium Propionate: "Not less than 3,260 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WT38440 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 0.1% |

| REL (Recommended) | 3000 mg/kg |

| Main hazards | May cause eye, skin, and respiratory tract irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319, P264, P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| Pictograms | GHS07 |

| Signal word | No signal word |

| Hazard statements | Not a hazardous substance or mixture according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008. |

| Precautionary statements | P264: Wash hands thoroughly after handling. P270: Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. P301+P312: IF SWALLOWED: Call a POISON CENTER/doctor if you feel unwell. P330: Rinse mouth. |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 1-0-0 |

| Flash point | > 250°C |

| Autoignition temperature | > 410°C (770°F) |

| Explosive limits | Not explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 (oral, rat): 3,040 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): 3,040 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH | WT3897000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | 0.5% |

| REL (Recommended) | 3000 mg/kg |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Sodium propionate Potassium propionate Propionic acid Calcium acetate Calcium lactate |

| Related compounds |

Propionic acid Sodium propionate Potassium propionate |