Aluminum Oxide: Past, Present, and Future

Historical Backdrop

Aluminum oxide’s roots trace back to the early days of chemistry, cropping up across industries and laboratories for well over a hundred years. The extraction of pure aluminum from ores like bauxite brought aluminum oxide, or alumina, into the spotlight. The Bayer process, first used at the end of the 19th century, pushed this powdered substance into mass production. Where earlier generations watched glassmakers and potters sprinkle it into glazes and ceramics, modern engineers see it powering everything from aircraft parts to microchips. Innovations in refining and processing this white powder have steadily improved its purity and expanded its reach far beyond the pottery wheel and metallurgist’s bench.

Product Rundown

Aluminum oxide doesn’t grab headlines, but it powers much of the technology we live with every day. As a white, odorless powder or crystalline solid, it serves as both workhorse and backbone. The grit in sandpaper? Often alumina. The layer protecting aluminum cans against corrosion? Once again, aluminum oxide. Dense, tough, and with a melting point well above 2,000°C, it’s the kind of material you don’t have to look for—because it finds its way everywhere.

Physical and Chemical Profile

Dense and hard, aluminum oxide stands firm even under crushing force. It scratches glass and resists heat: Mohs hardness 9, melting around 2,072°C, with a boiling point close to 2,977°C. Its density sits about 3.95–4.1 g/cm³, creating a substance both lightweight for ceramics yet heavy-duty for industrial use. Chemically, alumina resists most acids but yields to hot alkalis. Water barely fazes it; acids can’t easily dissolve it. An amphoteric behavior means it reacts as both acid and base, which opens doors for creative chemistry. Various crystalline phases take names like alpha, gamma, and theta, but the stable alpha form—corundum—drives the bulk of real-world applications.

Getting Specific: Technical Specs and Labeling

Most commercial grades specify purity (95–99.99%), particle size, and phase composition. Clients might check labels for trace impurities—iron, sodium, or silica—since these small amounts can sway electrical or catalytic performance. Identification comes by name, chemical formula (Al₂O₃), and registry numbers like CAS 1344-28-1. Terms like “activated alumina,” “tabular alumina,” and “fused alumina” distinguish how it’s processed and where it’s likely to work best. Sheets of specs usually accompany every shipment, ensuring any trace element that might alter conductivity, reactivity, or strength stays within tight limits.

Preparation and Sourcing Methods

Aluminum oxide owes much to the Bayer process. Workers crush bauxite and treat it with sodium hydroxide at high temperature and pressure. This dissolves the alumina, which separates from impurities like iron oxides. Later, the solution is cooled and seeded with aluminum hydroxide crystals, which draw the dissolved alumina out of the mix. Roasting this hydroxide at over 1,000°C leaves behind pure, white aluminum oxide. For higher densities or special physical forms, secondary steps like fusing or sintering produce crystals or pellets for abrasives, refractories, or electronics. Specialty grades use chemical vapor deposition or sol-gel methods, tailoring the form for high surface area catalysts or nano-engineered coatings.

Reactions and Modifications

Alumina plays well with others in complicated reactions. As an amphoteric oxide, it reacts with both acids and bases. Add hydrochloric acid, and it releases aluminum chloride. Stir in sodium hydroxide, and sodium aluminate comes out. By doping with ions like titanium or chromium, manufacturers tweak electrical or optical properties—ruby owes its red tint to chromium-laced aluminum oxide. Surface modification, such as creating mesopores or anchoring catalysts, turns it into a workbench for chemists intending to speed up or direct reactions. Its resistance to corrosion and reactivity in extreme environments mean it shows up in specialty ceramics, spark plugs, catalysts, and filtration media for purifying gases and liquids.

Common Names and Synonyms

In the lab, this staple takes names: alumina, aloxide, alundum, or simply aluminum oxide. The gem-quality version—corundum—slides onto jeweler’s benches as sapphire and ruby. Each trade applies its own lingo, but the chemical backbone remains Al₂O₃. Brands like Sumitomo and Saint-Gobain market tailored forms—sintered, activated, or fused—to meet niche needs across manufacturing, chemical processing, or polishing.

Safety Matters and Handling Rules

Sticking to best practices around alumina keeps workers safe. The powder irritates lungs if inhaled, though the risk remains low with proper ventilation and dust control. Direct skin or eye contact rarely leads to persistent problems—just rinse and move on. Nevertheless, plant managers install dust extractors and supply personal protective equipment just the same, working under mandates from OSHA and EU REACH guidelines. Bulk storage avoids moisture since wet alumina clumps and bridges, making handling tough. Combustion remains a non-issue, but static buildup in pneumatic conveying sometimes sparks extra training for operators. Labels flag the hazards, and material safety data sheets outline cleanup, exposure, and disposal guidelines, so plant floors and research labs can run without hiccups.

Where Aluminum Oxide Goes to Work

Aluminum oxide’s work ethic puts it to use just about everywhere. Abrasives and sandpapers chew through wood and metal thanks to its grit. Kiln linings and furnace bricks hold shape in steel mills and glass plants, built from dense, heat-resistant alumina. Water treatment facilities rely on its adsorptive power to pull fluoride from municipal supplies, while the electronics sector makes thin insulating films for microchips using ultra-pure forms. Chemists work with alumina columns in labs, separating complex mixtures with the white powder acting as an inert, dependable scaffold. Dentists use it for polishing enamel and making crowns that stand up to decades of chewing. LED makers and laser manufacturers build wafers from crystalline alumina, betting on its toughness and clarity under stress. Even rocket engineers lean on alumina to protect engines and withstand fiery exhaust.

On the Research Edge

Innovation in aluminum oxide finds momentum from materials science and nanotechnology. Teams push particle sizes down to nanoscale, where new properties emerge—higher surface areas, greater hardness, or unexpected reactivity. Researchers dig into ceramic-matrix composites, hoping alumina fibers or platelets will reinforce everything from body armor to airplane wings. In electronics, the push for smaller, faster devices demands ultra-clean, defect-free films—calling for new purification and deposition tricks. Environmental researchers look at how alumina can filter new contaminants or catalyze the breakdown of pollutants with precision. University labs and startups alike chase breakthroughs in biomedical devices, energy storage, and next-generation lasers, often placing alumina at the core.

Questions of Toxicity

Most studies clear aluminum oxide for industrial and consumer use, though questions flit around the edges of very fine particles. Inhaling large amounts of dust long-term can lead to mild lung irritation, but studies so far haven’t linked it to silicosis or chronic ailments. Oral exposure, common in water from pipes with aluminum coatings, hasn’t produced strong evidence of harm at the concentrations typically encountered. Researchers in the nanomaterials field keep a watchful eye, questioning whether particles crossing cell membranes could behave differently from traditional forms. Animal tests flag little acute toxicity, with the bulk of risk tied to specific high-risk industrial exposure rather than everyday consumer goods. Regulatory agencies stay in the loop, ready to review new findings and tighten standards if new risks emerge.

On the Horizon

As manufacturing and technology race ahead, aluminum oxide finds itself at the center of fresh opportunities. Markets demand lighter vehicles; industry wants stronger, more heat-resistant parts. Alumina stands ready, moving into 3D printing powders, transparent armor, and microelectronic insulation. Advances in recycling could help close production loops, keeping environmental footprints low while meeting demand for greener supply chains. On the nanotechnology front, research hints at roles in medicine, such as slow-release drug carriers or scaffolds for growing new tissues. Engineers and scientists keep probing for new angles—hoping the same material that once lined crucibles might soon help cure diseases, enable new forms of computing, or shield spacecraft on Mars landings.

What are the main uses of Aluminum Oxide?

What Makes Aluminum Oxide Special?

Aluminum oxide often brings to mind images of sandpaper and grinding wheels, but its reach stretches far past the hardware store aisle. For a lot of people, including myself with experience in basic home repairs and a chemistry background, it’s hard not to notice how widely this material shows up once you keep an eye out for it. It stands tough, resists corrosion, and refuses to melt until things get blazing hot. These qualities drive its many roles in modern life.

Abrasive Powerhouse

Walk into any workshop and look at the grinding and polishing tools. Most have aluminum oxide as the cutting muscle. Its natural hardness rivals sapphires and rubies. I’ve used aluminum oxide sandpaper to smooth rough planks and strip rust off old tools. It bites into metal, wood, and stone without wearing out quickly, which keeps costs lower and work speeds faster. Major industries follow this path, using aluminum oxide in blasting, cutting, and finishing everything from car parts to dental tools.

Ceramics and Refractories

This material also builds bones for some of the most heat-resistant stuff people can make. Inside kilns, furnaces, and foundries, you’ll find bricks and linings built from aluminum oxide. A few years back, I helped set up a gas forge. The lining caked inside held up blow after blow from the heat, spitting sparks and never budging. Beyond workshops, power stations and steel plants put their trust in these bricks to keep things safe despite relentless fire and corrosion risks.

Electronics and High-Tech Applications

Flip over a smartphone or poke around inside a computer lab, and the silent work of aluminum oxide comes into focus. This material acts as an insulator in tiny circuits, stopping unwanted electrical leaps that could fry sensitive parts. It also appears as a thin protective layer on certain chips, shielding them from moisture and dust. A layer of aluminum oxide just a couple atoms thick helps push technology forward, making the gadgets in our pockets and homes faster, smaller, and more reliable.

Helping in Medicine

Medicine takes advantage of aluminum oxide too, especially in artificial joints and dental crowns. Its extreme hardness keeps hip and knee replacements moving smoothly for years without grinding down. In my own family, relatives with artificial joints walk comfortably thanks in part to this unsung material. Dentists turn to it when crafting fillings or crowns strong enough to chew for decades. The reasons behind its popularity in clinics and hospitals are clear: patients expect long-lasting, reliable fixes, and aluminum oxide delivers.

Water Purification and Filtration

Clean water stands as a basic need, but getting it free from harmful stuff often requires high-tech help. Aluminum oxide acts as a filtering agent in water treatment systems, trapping suspended solids and absorbing chemicals such as fluoride. Public water plants and smaller home filters both count on its porous structure and reliable behavior. Whether in cities dealing with industrial runoff or smaller towns watching for natural mineral contamination, aluminum oxide quietly helps keep water safer to drink.

Paths Toward Responsible Use

So much demand for aluminum oxide tests supply chains and resources. Bauxite mining, the main source, scars land and produces waste. Smarter recycling and finding less destructive extraction methods will make a big difference. Research groups work on ways to reuse spent abrasives and recover valuable parts, aiming for a loop rather than a straight line from mine to landfill. Having industry leaders and governments invest in cleaner production practices matters, because this resource deserves future use as much as it supports today’s world.

Is Aluminum Oxide safe to use?

Recognizing What Aluminum Oxide Is

Aluminum oxide shows up sprinkled across a lot of industries—sandpaper, toothpaste, ceramics, and even as a food additive. Some people call it Alumina, but it’s the same compound, basically powdered aluminum mixed with oxygen. If you’ve ever handled sandpaper or gotten a dental cleaning, you’ve likely met aluminum oxide. In many workplaces or garage DIY setups, it’s everywhere.

Worker Experience and What Actual Exposure Looks Like

Making things smoother or tougher—these are the goals for folks who choose aluminum oxide. As someone who’s spent time around fabrication and dental labs, I’ve seen folks using it to blast clean surfaces or polish teeth. They wear masks and goggles, and they keep the dust controlled. The reason: inhaling fine aluminum oxide particles for a long time irritates the lungs, just like breathing in sawdust or flour dust would. The worst cases crop up when the safety gear sits unused and dust clouds fill the air, especially in cramped shops.

Research backs up those real-world stories. Multiple toxicology reports show that standard, short-term contact with skin or even in food doesn’t harm healthy people. Chronic, heavy inhalation—meaning years of breathing the dust every workday—links to mild lung irritation, but not the lung scarring or cancer seen with asbestos or silica. Reports from OSHA and NIOSH keep their recommended limits tight, mostly to keep workers comfortable and reduce coughing or sneezing.

Using It in Everyday Products

Rubbing elbows with aluminum oxide also happens more quietly: toothpaste gives your teeth that polish with its fine crystals, and medications use it as a thickener. The FDA classifies aluminum oxide as “Generally Recognized As Safe” (GRAS). Medical researchers looked for any sign that eating it up in small doses, like from food additives or medicine, builds up in the body. Tests show our guts barely absorb aluminum from this form, and the tiny bit that slips through leaves through urine with no harm.

Ceramics, spark plugs, and even electronics get their strength and insulation from aluminum oxide, but sealed inside, it never escapes into the air or food. For the most part, only bulk powder or abrasive use invites any risk.

Keeping Safe: What Actually Works

Pulling from health and safety best practices, people who use aluminum oxide as an abrasive, either in blasting machines or sandpaper, stick to simple protection: masks for dust, gloves to stop skin irritation, and plenty of air flow. Companies post safety sheets outlining how to clean up spills or avoid too much dust in the air. Training workers to actually use those tools and spot symptoms early saves a lot of headaches.

Community awareness helps. Some people with aluminum allergies—or rare kidney problems—should talk to a doctor before swallowing large doses, but for most, regular products stay solidly in the safe zone. Government and health agencies keep close tabs, updating recommendations anytime new science appears.

Growing Trust in What Science Shows

Aluminum oxide isn’t mysterious. Generations of workers have handled it safely with good habits and simple equipment. Industry watchdogs like OSHA, the FDA, and international health groups check the latest evidence and adjust their advice as needed. Paying attention to those updates keeps safety front and center, and after years spent around factories and clinics, I’ve seen firsthand that sticking to those basics—ventilation, masks, gloves—lets people use aluminum oxide with as little worry as they would using table salt.

What are the physical and chemical properties of Aluminum Oxide?

Toughness Built In: The Physical Side

Aluminum oxide, also called alumina, always brings to mind those ruby-red sandpaper sheets in the garage and the sparkling surface of gemstones like sapphires. This stuff is hard—really hard. Its Mohs hardness stands around 9, which puts it only one notch below diamond. Lab folks throw it in with drill bits and grinders because it handles a beating without losing its edge. Hardcore heat doesn’t throw it off, either. Its melting point sticks at a scorching 2,072°C (3,762°F), which blows past most metals used in regular industries. Whenever I saw it used in furnace linings or in welding, it stood up to fiery conditions that would ruin most materials.

Aluminum oxide doesn’t dissolve in water. Pour rain or splash acids on a ceramic mug glazed with it, you won’t see a hint of cloudiness or damage. You’ll notice it’s not all about being rock-solid—it also refuses to conduct electricity under normal conditions. Electrical folks choose it as an insulator when metal won’t cut it. Yet, in high-temperature situations, alumina steps up as an ionic conductor. That mix of tough and stable means manufacturers line microchips and lights with it, not to mention use it in medical implants and artificial joints, where durability and chemical deadliness both matter.

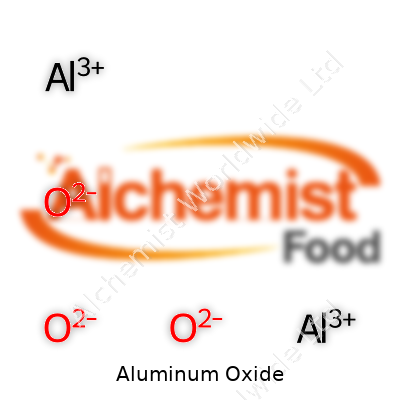

Chemistry Where It Counts

Now, take a look at what’s happening at the atomic level. Aluminum oxide’s formula, Al2O3, keeps it simple—two aluminum atoms for every three packed oxygens. But, these atoms stack in a way that resists corrosion. Throw acids or bases at it, and it won’t budge unless you crank things up with strong chemicals like hydrofluoric acid or hot, concentrated alkali. This means neither weather nor sweat can attack that protective coat on aircraft parts or window frames. Every time I’d see rust stain an iron fence but not the painted aluminum gate, that’s alumina quietly doing its job.

Aluminum oxide is called “amphoteric” in the lab. That simply means it won’t back down from either acid or base, making it a keen material for chemists who want to filter stuff or separate certain chemical compounds. Forget gold or silver—alumina grabs what it needs, thanks to all those loosely bound oxygen atoms. It acts like a sponge with charged surfaces, trapping metals and ions when cleaning up wastewater or in big chemical refineries. That knack for binding things shows up in water treatment plants and in gas refining, where impurities can’t slide past.

Why It Matters, Right Down to Practical Solutions

Walk through a hospital, and you’ll often see artificial joints and ceramic blades that never rust. Surgeons pick alumina-based implants for hips and teeth because infections rarely get a grip, and tissues seem to like the material. In electronics, makers rely on its ability to keep heat in check without letting currents sneak where they shouldn’t. Alumina lines the insides of everything from microchips to LEDs, keeping gadgets from burning out.

One big challenge comes when recycling. Most folks barely register the thin layer of alumina that forms almost instantly on aluminum cans. That stubborn, clear coating resists most smelting processes, so recyclers spend extra energy and money getting pure aluminum back. Innovators look at new ways—maybe advanced electrolytic or chemical processes—to strip or reuse this oxide so that less waste piles up and energy use drops.

The tough, chemically stubborn qualities of aluminum oxide have kept it a mainstay in manufacturing, medicine, and electronics, not just as a protective layer, but as an ingredient that boosts the life and performance of products. Its hidden role shapes much of the stuff we use, touch, and trust every day.

How is Aluminum Oxide produced?

From Dirt to Industry

My first job out of college landed me near an old refinery, with red dust that turned everything—my boots, the local stray dogs, even the leaves—rust-colored. That dust came from bauxite, the gritty rock at the start of the aluminum oxide story. Most folks don’t spend much time thinking about alumina, but it turns up all over: in smartphone screens, in sandpaper, in the paste dentists use to polish your teeth. Before any of it shines, bauxite has to survive one of the messiest transformations in modern chemistry.

The Gritty Side of Chemistry

Every ton of alumina starts as about two tons of bauxite, dug up in Australia, Guinea, Vietnam, and other hot, sticky places. This ore doesn’t give up its goods for free. Big trucks haul it to refineries, where crews crush the rock and mix it with hot sodium hydroxide. That stuff, known around factories as caustic soda, does the heavy lifting. It tears the aluminum out of the rock, leaving a thick, red sludge behind. Folks in the business call it "red mud", and cleaning up after it costs nearly as much as making the alumina in the first place.

Once the soda dissolves the aluminum, dense filters catch the leftover junk—iron, silica, and everything else that never made the grade. Liquid flows away, trucked to settling tanks. Here, crystalline particles of aluminum hydrate fall from the solution, like frost growing on a window as the day cools. The trick comes from an old industrial habit: seed crystals, made from earlier batches, encourage new crystals to form quickly and cleanly.

Into the Furnace

Wet hydrate doesn’t last—it has to go through fire. Conveyors load it into big rotary kilns or fluidized bed calciners, running at nearly 1,000°C. Heat strips out water and leaves behind fine, sparkling white powder. This is aluminum oxide, or alumina, as pure as science gets. At this stage, that powder is ready for all sorts of lives. Packaging might ship it off to become smelter feedstock for lightweight airplane bodies, or for growing sapphires used in lasers. Sometimes, it heads for ceramics or high-end abrasives.

The Red Mud Problem

Trouble sticks around. For every ton of finished aluminum oxide, more than a ton of red mud piles up. In the past, factories dumped it in ponds behind dams, just out of sight. In 2010, Hungary’s reservoirs broke and red sludge swamped villages, killing wildlife and giving a fresh reminder that industry rarely cleans up after itself overnight.

Some companies try recycling the mud—extracting rare earth metals or making bricks. Most solutions cling to the margins, slowed down by price and politics. Real progress still needs strict oversight, investment, and a nudge from governments to squeeze more out of the leftovers.

Why All This Matters

Aluminum oxide production relies on resources, chemistry, and tough decisions. Workers on the ground see the shifting red landscapes. Engineers push for safer, cleaner ways to run refineries. Consumers rarely connect their gadgets or kitchen foil to faraway mines. Real progress in this space means smarter regulation, new tech for mud recycling, and some honest conversations about our appetite for convenience. Nobody escapes the consequences of what we dig up and refine—even if the powder seems clean by the time it arrives in the next product.

Can Aluminum Oxide be used as an abrasive?

Abrasives in Everyday Life

Ask folks in the auto shop or the woodworking room about their favorite abrasive. One material pops up often: aluminum oxide. Some people just call it "alumina," and anyone who works with metal, wood, or even stone keeps it close at hand. No fancy laboratories needed—walk through any hardware store and you’ll find it glued to sandpaper, spinning in grinding wheels, and packed into polishing belts.

Why Aluminum Oxide Actually Gets the Job Done

You won’t find many who complain about how aluminum oxide cuts. It works because it’s tough. With a Mohs hardness that rivals a good diamond—a solid 9 on the scale—these tiny crystals chew through rust, paint, or metal with energy left over. Compared to silica sand, which actually breaks down and goes dull fast, alumina stays sharp as it fractures. Each break reveals a new edge, so that sanding disc just keeps on going.

I learned the hard way working in a garage: use cheap sand and watch your sandpaper clog and burn out in a heartbeat, or step up to alumina and see the difference in speed. My own knuckles have seen fewer nicks thanks to using an abrasive that keeps biting until the job is actually done.

Dust, Efficiency, and Safety

Performance alone can’t be the whole story. Sometimes shop safety gets forgotten in the rush to finish a project. Breathing in silica dust, for example, invites serious health problems over time—think silicosis and other lung troubles documented by OSHA and CDC. Alumina doesn’t carry the same immediate risks, though it’s smart to wear a simple dust mask with any fine particle. Alumina dust is inert, less likely to cause those long-term illnesses, so switching to this abrasive already puts you ahead.

Industrial Use and Everyday Solutions

It isn’t all tradition and legacy, either. Factories grinding chrome steel parts, shoe repair shops smoothing boot heels, glass engravers etching custom trophies—all of them trust alumina’s staying power. Engineers count on repeatable results. Its grit sizes range from oversized chunky grains to flour-like powders, so it shapes, polishes, cleans, and refines. Broken items like old tools can get a second life when blasted with the right grade of aluminum oxide.

Uniformity in grain size matters if you want an even finish—nobody enjoys patchy work. Some users want coarse buffing, others chase a mirror polish. Alumina adapts by supplying a range that suits both. It’s less a one-trick pony, more of a Swiss Army knife for abrasive jobs.

Pushing for Better Practices

Reliability aside, the conversation about abrasives today often includes the environment. Reusing old aluminum oxide after blasting helps cut down waste. Companies now design reclaiming systems to collect spent grit and filter out debris. This cycle saves money over the long haul and keeps use sustainable, reducing strain on raw materials. Some outfits pressure-wash alumina grit so it’s ready for repeat rounds—good for the shop, even better for the planet.

Aluminum oxide earned its place as a trusted abrasive not because it’s the flashiest, but because it works. From humble garages to precision tooling plants, its presence keeps projects moving and workers safe. Choosing quality abrasives doesn’t just save time; it protects your lungs, your budget, and—when reused—your surroundings, too.

| Names | |

| Preferred IUPAC name | dialuminium trioxide |

| Other names |

Alumina Aluminium(III) oxide Alpha-alumina Aloxite Corundum |

| Pronunciation | /əˌluː.mɪ.nəm ˈɒk.saɪd/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name | dialuminium trioxide |

| Other names |

Alumina Alpha-alumina Aluminum trioxide Aluminium(III) oxide |

| Pronunciation | /əˌluː.mɪ.nəm ˈɒk.saɪd/ |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | 1344-28-1 |

| Beilstein Reference | 1000174 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30165 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1200438 |

| ChemSpider | 21169694 |

| DrugBank | DB11255 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.008.944 |

| EC Number | 215-691-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 37988 |

| KEGG | C08375 |

| MeSH | D000576 |

| PubChem CID | 9989226 |

| RTECS number | BD1200000 |

| UNII | ALV1MUP43M |

| UN number | UN3077 |

| CAS Number | 1344-28-1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | Aluminum Oxide (Al₂O₃) JSmol 3D model string: ``` Al2O3 ``` |

| Beilstein Reference | 133–714–7 |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:30109 |

| ChEMBL | CHEMBL1201751 |

| ChemSpider | 16212221 |

| DrugBank | DB01370 |

| ECHA InfoCard | ECHA InfoCard: 100.013.151 |

| EC Number | 215-691-6 |

| Gmelin Reference | 67722 |

| KEGG | C14321 |

| MeSH | D000555 |

| PubChem CID | 9989226 |

| RTECS number | BD1200000 |

| UNII | LZV6CL4D2U |

| UN number | UN3469 |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | Al2O3 |

| Molar mass | 101.96 g/mol |

| Appearance | White, odorless, crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.95 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble |

| log P | -0.48 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Basicity (pKb) | 10.6 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +3.8×10⁻⁵ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.762 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Chemical formula | Al2O3 |

| Molar mass | 101.96 g/mol |

| Appearance | white odorless crystalline powder |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 3.95 g/cm³ |

| Solubility in water | Insoluble |

| log P | 0 |

| Vapor pressure | Negligible |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~9.0 |

| Basicity (pKb) | 15.74 |

| Magnetic susceptibility (χ) | +2.2·10⁻⁵ |

| Refractive index (nD) | 1.768 |

| Dipole moment | 0 D |

| Thermochemistry | |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 50.9 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | –1675.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | -1676 kJ/mol |

| Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 50.9 J/(mol·K) |

| Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | -1675.7 kJ/mol |

| Std enthalpy of combustion (ΔcH⦵298) | −1676 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| ATC code | V07BB |

| ATC code | A06AD04 |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS07, Warning, H319 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P280, P305+P351+P338, P304+P340, P312 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | 0-0-0 |

| Explosive limits | Non-explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral Rat: > 5000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): >5,000 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | RN# 1009 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) of Aluminum Oxide is "15 mg/m³ (total dust), 5 mg/m³ (respirable fraction)". |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 mg/m3 |

| Main hazards | May cause respiratory irritation. Causes serious eye irritation. Causes skin irritation. |

| GHS labelling | GHS02, GHS07 |

| Pictograms | GHS07,GHS08 |

| Signal word | Warning |

| Hazard statements | H319: Causes serious eye irritation. |

| Precautionary statements | P280, P305+P351+P338, P337+P313 |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | Health: 2, Flammability: 0, Instability: 0, Special: - |

| Explosive limits | Non-explosive |

| Lethal dose or concentration | LD50 Oral - rat - > 5,000 mg/kg |

| LD50 (median dose) | LD50 (median dose): >5000 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| NIOSH | AN9000 |

| PEL (Permissible) | PEL (Permissible Exposure Limit) for Aluminum Oxide: 15 mg/m³ (total dust), 5 mg/m³ (respirable fraction) as an 8-hour TWA (OSHA) |

| REL (Recommended) | 10 mg/m3 |

| IDLH (Immediate danger) | Unknown |

| Related compounds | |

| Related compounds |

Aluminum hydroxide Aluminum nitride Aluminum sulfate Aluminum chloride Gallium(III) oxide Indium(III) oxide |

| Related compounds |

Aluminum hydroxide Aluminum nitride Aluminum sulfate Alumina hydrate |